Lem and Solaris: The Unknowable Other

In 1961, Stanisław Lem published Solaris—a novel about alien contact that refuses to deliver what alien contact stories usually deliver.

There is no communication. No understanding. No translation protocol that cracks the code. The alien ocean covering the planet Solaris does things—manifests constructs, responds to stimuli, creates matter from nothing—but no one understands why.

Scientists have studied Solaris for decades. Libraries of theories exist: 247 different hypotheses about the ocean's nature. None are verified. None are refuted. The ocean remains epistemically opaque.

Lem's point wasn't that aliens are merely difficult to understand. It was that some things might be impossible to understand—that consciousness, reality, or the universe itself might contain entities that exceed human comprehension by design, not just by accident.

This is the unknowability paradigm. Not chaos, not complexity, not statistics—but fundamental limits on what minds like ours can grasp.

The Failure of Solaristics

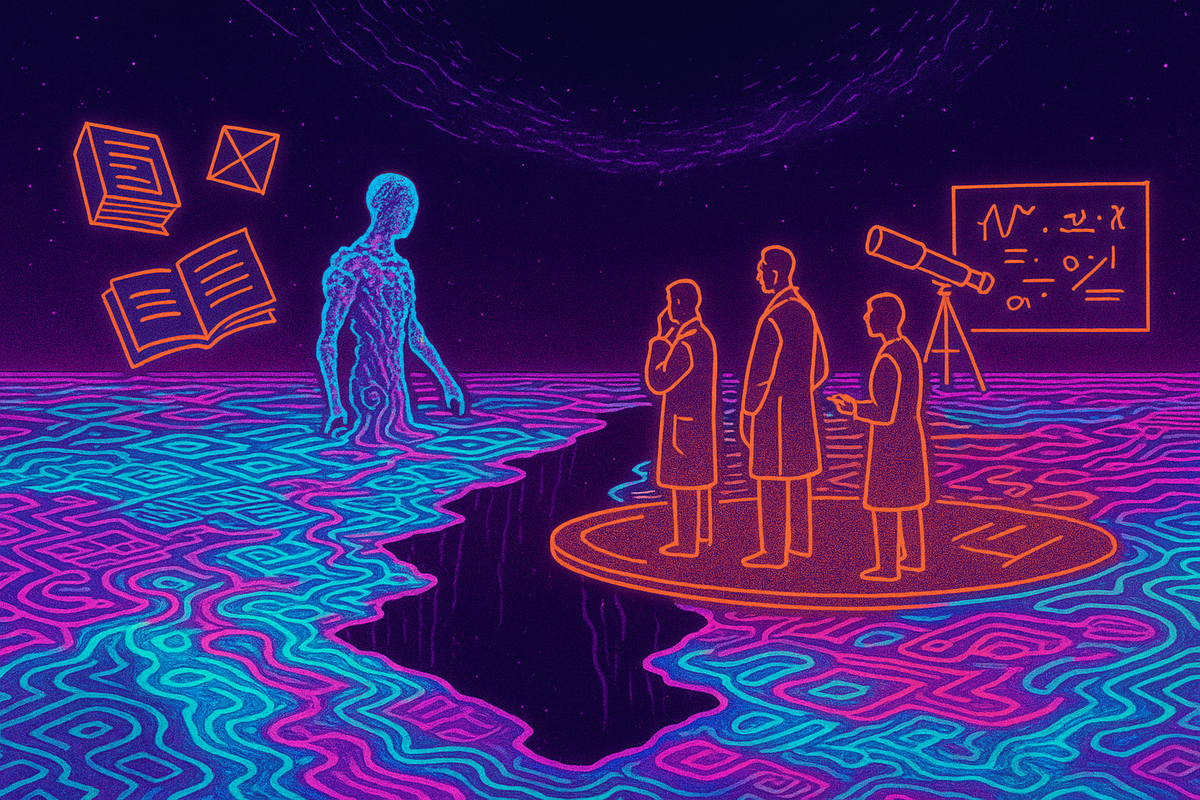

The scientists in Solaris have a problem worse than lacking data.

They have too much data. The ocean produces formations—symmetriads, mimoids, agilus—that they can describe in exhaustive detail. They build taxonomies of phenomena. They catalog patterns.

But the patterns don't add up. Every theory that explains one phenomenon fails to explain another. Every framework that seems promising runs into exceptions. The ocean appears to act intentionally—but no intention can be inferred. It appears to respond—but the responses don't form a coherent communication.

Solaristics—the science of Solaris—is the ultimate failed research program. Brilliant minds have devoted careers to understanding the ocean. They've produced shelves of books, catalogued thousands of observations, generated and tested hundreds of hypotheses.

And they know nothing more than they knew at the start.

The Visitors

Then something worse happens.

The ocean begins producing "visitors"—material recreations of people from the scientists' memories. Usually dead loved ones. Usually figures of guilt or longing.

The protagonist, Kris Kelvin, finds his cabin occupied by Harey—his ex-wife who committed suicide years ago. She looks like Harey, talks like Harey, doesn't know she's a construct.

Kelvin shoots the first Harey into space. Another appears. He tries to destroy her. She regenerates. She cannot be killed. She is not a person—she's composed of some unknowable substrate that the ocean manufactured. But she believes she's human. She loves him. She wants to be with him.

The visitors are the ultimate epistemological horror. Not because they're threatening—but because they're meaningful without being comprehensible. The ocean created Harey. Why? To communicate? To torture? To study human reaction? To satisfy some alien aesthetic sense?

There is no answer. The ocean offers no explanation. The visitors simply are.

The Limits of Science

Lem was a skeptic about the triumphalism of science.

Not that science doesn't work—it does, in its domain. But Lem questioned whether that domain was unlimited. He questioned whether human cognitive architecture could, in principle, comprehend everything the universe might contain.

Most science fiction assumes the opposite. Alien civilizations are mysterious initially but comprehensible eventually. First contact is a translation problem. Given enough time and effort, we'll understand.

Lem rejected this. Some things might be genuinely other. Not strange versions of the familiar, but alien in a more fundamental sense—entities whose being operates on principles our minds cannot represent.

The ocean of Solaris is not a puzzle to be solved. It's an encounter with the limits of human understanding.

The God Question

Lem plays with religious language throughout Solaris.

The ocean is sometimes described as a god—but a defective god, an "imperfect god" who "created universes but was creating himself at the same time." A god that doesn't know what it's doing. A god that experiments.

The scientists debate whether Solaris is conscious, whether it has intentions, whether it can be said to "want" anything. The answers matter—a conscious Solaris might be communicated with; an unconscious Solaris is just a phenomenon.

But Lem refuses to resolve the question. The ocean might be conscious. It might not be. The visitors might be communication attempts. They might be random outputs. There's no way to know.

This is the theological limit applied to science fiction. We face phenomena we cannot categorize as intentional or mechanical, conscious or automatic, meaningful or random. The categories themselves might not apply.

The Mirror Problem

The visitors are mirrors—literally, recreations from the scientists' memories.

But what kind of mirror is the ocean? Is it reflecting human content back at humans? Is it studying how humans react to their own projections? Is it creating art? Is it indifferent?

Lem suggests that the ocean might be as baffled by humans as humans are by it. The visitors might be the ocean's attempt to understand human consciousness—experiments that fail as badly as human experiments on the ocean.

What if first contact is mutual incomprehension? Not because we haven't tried hard enough but because the gap between minds is uncrossable. What if the universe contains intelligences so different from ours that "intelligence" is the wrong word—that the concept doesn't bridge the gap?

This is the dark possibility Lem explores. Not just that aliens are weird, but that alienness might be absolute.

The Tarkovsky Adaptation

Andrei Tarkovsky filmed Solaris in 1972. His version emphasizes the human emotional content—Kelvin's guilt, his relationship with Harey, his longing for connection.

The Soderbergh remake (2002) does the same—it's a love story with science fiction trappings.

Both miss Lem's point. Lem wasn't writing about human emotional processing. He was writing about the failure of human cognition to grasp the genuinely alien.

The emotional adaptations domesticate the novel. They make it about what we can understand—love, guilt, loss. The ocean becomes a backdrop for human drama.

Lem's ocean is not a backdrop. It's the subject. And the subject is irreducibly unknowable.

The Epistemological Horror

Lovecraft invented cosmic horror: entities so vast and alien that contact with them destroys human sanity.

Lem invented epistemological horror: entities so different that contact with them reveals the limits of human knowing—and leaves us unable to even formulate our confusion.

Lovecraft's horror is overwhelm. Cthulhu is too much for the mind to process. The response is madness.

Lem's horror is emptiness. Solaris is not too much but too different. The response is not madness but frustration—the awful clarity that you're not going to figure this out. Not because you're not smart enough, but because the thing exceeds the categories of smartness.

The Paradigm of Limits

Solaris reflects a specific paradigm: epistemic boundedness.

Other paradigms assume we can know things: - Mechanical determinism: know the parts, know the whole - Statistical determinism: know the distribution, know the aggregate - Computational universe: know the code, know the output

Epistemic boundedness says: some things exceed what we can know in principle.

This might be true. Gödelian limits show that formal systems can't prove their own consistency. Quantum mechanics shows that certain properties can't be simultaneously measured. Halting problems show that certain computations can't be predicted.

What if alien consciousness is a halting problem? What if there's no algorithm that translates ocean-thought into human-thought? What if the incomprehension is mathematical, not just practical?

What Lem Says About First Contact

Most first contact stories are optimistic. We meet aliens. Initial confusion. Eventual understanding. Handshakes across the stars.

Lem says: maybe not. Maybe first contact is permanent incomprehension. Maybe the alien minds are alien in ways that block translation. Maybe we'll stand on alien planets, surrounded by alien structures, watching alien behaviors—and never understand any of it.

This is not a failure of effort. It's a feature of reality.

The universe might contain intelligence that intelligence cannot recognize. The boundaries of cognition might be real, and some things might lie outside them.

Lem showed us what that would feel like: the endless library of Solaristics, the regenerating visitors, the ocean that acts but cannot be interpreted. A universe containing things that make no sense—not because they're meaningless, but because we are incapable of grasping their meaning.

The Synthesis with Other Paradigms

Where does Lem fit in the paradigmatic landscape?

Dune: You can see the attractor but not escape it. Matrix: You can hack the system if you find the code layer. MCU: Every possibility exists; choose your branch. Foundation: Statistics reveal the aggregate. Solaris: Some things cannot be known.

Lem adds the limit case. Most paradigms assume knowability. They differ about what's predictable, escapable, controllable—but they share the assumption that sufficiently advanced understanding can model reality.

Lem questions that assumption. He suggests that the universe might contain irreducible mystery—not mysticism, not magic, but genuine limits on what minds can comprehend.

This is the hardest paradigm to accept. We want to believe that more knowledge, more analysis, more intelligence will eventually crack every problem. Lem suggests: maybe not. Maybe some problems are permanent.

Further Reading

- Lem, S. (1961). Solaris. Translated by Joanna Kilmartin and Steve Cox. Walker and Company, 1970. - Csicsery-Ronay, I. (2012). "The Book Is the Alien: On Certain and Uncertain Readings of Lem's Solaris." Science Fiction Studies. - Lem, S. (1974). "Cosmology and Science Fiction." Science Fiction Studies.

This is Part 7 of the Science Fiction Mirror series. Next: "Black Mirror and Feedback Loops: Tech as Trap."

Comments ()