Line Integrals: Integrating Along Curves

Line integrals let you sum up a vector field along a curve. They answer the question: "How much does this field accumulate as you move along this path?"

In single-variable calculus, you integrate over an interval. The domain is one-dimensional, and you're summing up values of a function. Line integrals extend this to curves in higher dimensions. The path can wind through 2D or 3D space, and you're summing up projections of a vector field along that path.

The canonical application is work. If F is a force field and C is a path through space, the line integral ∫_C F · dr is the work done by the force on a particle moving along C. You're summing up tiny bits of force-times-distance at each point on the path.

But line integrals show up everywhere: circulation in fluid flow, voltage in electric circuits, mass along a wire, energy transport in physics. Anytime you need to accumulate something along a path, you use a line integral.

The Setup

You have a vector field F(x, y, z) and a curve C parameterized by r(t) = (x(t), y(t), z(t)) for t in [a, b].

The curve might be a straight line, a circle, a helix, whatever. The parameterization describes how you traverse the curve as t varies. At each value of t, r(t) gives you a position in space.

The line integral of F along C is:

∫_C F · dr = ∫_a^b F(r(t)) · r'(t) dt

Let's unpack this:

- F(r(t)) is the vector field evaluated at the point on the curve. You're sampling the field at each location along the path.

- r'(t) is the derivative of the parameterization—the tangent vector to the curve. It points in the direction you're moving and has magnitude equal to speed.

- F(r(t)) · r'(t) is the dot product. It projects the field vector onto the tangent direction. Only the component of F parallel to the path contributes. Perpendicular components cancel out.

- ∫_a^b ... dt integrates over the parameter interval. You're summing up contributions from every infinitesimal segment of the curve.

The result is a single number: the total accumulation of the field along the path.

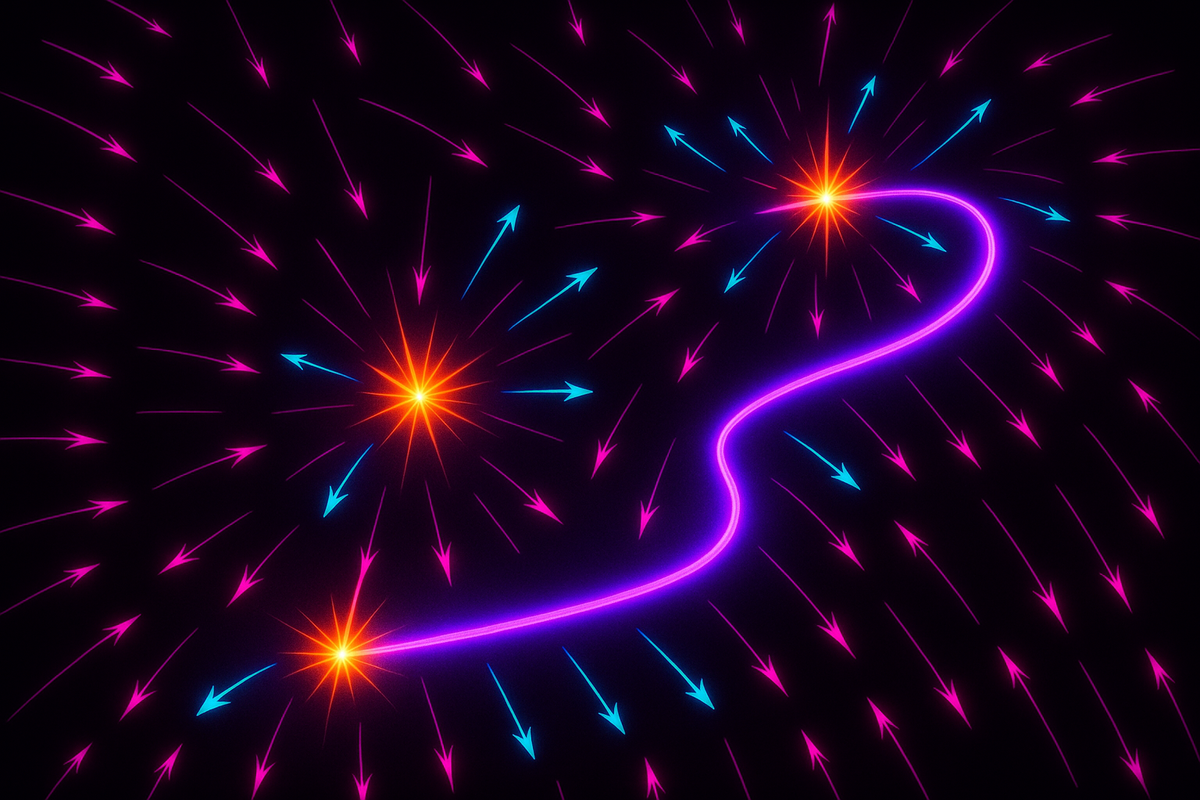

The Geometric Picture

Imagine walking along the curve. At each point, the vector field points in some direction with some magnitude. You take the component of that field in the direction you're walking—that's the dot product F · T, where T is the unit tangent.

If the field points along your direction of motion, the contribution is positive. If it points backward, the contribution is negative. If it's perpendicular, there's no contribution.

You sum up all these signed contributions as you walk the entire path. That's the line integral.

For a force field, this is literally work. When you push something, work = force · distance, but only the component of force in the direction of motion counts. The line integral sums this up over the entire path.

For a velocity field, the line integral measures circulation. How much does the flow "go around" the path? If the field aligns with the curve, circulation is high. If it opposes the curve, circulation is negative.

Computing Line Integrals: Example

Let F(x, y) = (-y, x), a counterclockwise rotating field around the origin.

Let C be the unit circle, parameterized by r(t) = (cos t, sin t) for t in [0, 2π].

Then r'(t) = (-sin t, cos t).

F(r(t)) = F(cos t, sin t) = (-sin t, cos t).

F(r(t)) · r'(t) = (-sin t)(- sin t) + (cos t)(cos t) = sin²t + cos²t = 1.

∫_C F · dr = ∫_0^{2π} 1 dt = 2π.

The line integral is 2π. This makes sense geometrically: the field circulates around the origin, and the unit circle goes once around, accumulating 2π worth of circulation.

If we had integrated around the circle in the opposite direction (parameterized by t from 2π to 0, or equivalently reversing the sign of r'(t)), we'd get -2π. Direction of traversal matters.

Path Independence and Conservative Fields

For some vector fields, line integrals depend only on the endpoints, not on the path taken. These are called path-independent or conservative fields.

A field F is conservative if and only if F = ∇φ for some scalar function φ (the potential). In this case:

∫_C F · dr = φ(end) - φ(start)

The line integral is just the difference in potential values at the endpoints. The path doesn't matter.

This is the generalization of the fundamental theorem of calculus. For F = ∇φ:

∫_C ∇φ · dr = ∫_a^b ∇φ(r(t)) · r'(t) dt = ∫_a^b (d/dt)φ(r(t)) dt = φ(r(b)) - φ(r(a))

The chain rule turns the line integral into a single-variable integral of a derivative, which evaluates to endpoint differences.

Examples of conservative fields:

- Gravitational fields (φ is gravitational potential energy)

- Electrostatic fields (φ is voltage)

- Any gradient field by definition

Examples of non-conservative fields:

- Magnetic fields

- Rotating velocity fields (like F = (-y, x))

- Friction forces

For conservative fields, closed-loop line integrals are always zero. You start and end at the same point, so φ(end) - φ(start) = 0. For non-conservative fields, closed-loop integrals can be nonzero—that's circulation.

Testing for Conservativeness

How do you tell if a field is conservative? In 2D, F = (P, Q) is conservative if and only if:

∂P/∂y = ∂Q/∂x

This is the condition for the curl to be zero (more on curl later). If the mixed partials of the components match, the field is conservative.

In 3D, F = (P, Q, R) is conservative if:

∂Q/∂z = ∂R/∂y, ∂P/∂z = ∂R/∂x, ∂P/∂y = ∂Q/∂x

Again, these are the conditions for zero curl. Conservative fields have no rotation.

If a field passes this test, you can find the potential φ by integrating:

φ(x, y) = ∫ P dx (treating y as constant) + g(y)

Then differentiate with respect to y and match to Q to find g(y).

This procedure reconstructs the potential from the field components. Once you have φ, computing line integrals is trivial—just evaluate φ at the endpoints.

Work and Energy

The canonical physical interpretation of line integrals is work.

Work = ∫_C F · dr, where F is force and C is the path.

If the force is conservative (like gravity or a spring), work is path-independent. The work done equals the change in potential energy: W = -ΔU.

If the force is non-conservative (like friction), work depends on the path. Longer paths mean more work done against friction.

The work-energy theorem says the total work done on an object equals its change in kinetic energy:

∫ F · dr = ΔKE

For conservative forces, W = -ΔU, so ΔKE = -ΔU, giving KE + U = constant. That's conservation of energy.

For non-conservative forces, energy isn't conserved. The line integral captures the energy dissipated or added by those forces.

This is why line integrals matter in mechanics. They're the mathematical tool for calculating work, which is the bridge between force and energy.

Circulation and Flux (2D)

In 2D, there are two types of line integrals worth distinguishing:

Circulation integral: ∫_C F · dr

This measures how much the field flows along the curve. It's what we've been discussing.

Flux integral (across the curve): ∫_C F · n ds

This measures how much the field crosses the curve perpendicularly. Here, n is the unit normal to the curve (perpendicular to the tangent), and ds is the arc length element.

Circulation sums the tangential component of F. Flux sums the normal component.

For closed curves, circulation relates to curl inside the region (Green's Theorem). Flux relates to divergence inside the region.

Both are line integrals, but they measure different things. Circulation is about "going around." Flux is about "crossing through."

Parameterization Independence

Line integrals are independent of parameterization (as long as orientation is preserved). You can parameterize the same curve in infinitely many ways, and the line integral will be the same.

Example: A straight line from (0, 0) to (1, 1) can be parameterized as:

- r(t) = (t, t) for t in [0, 1]

- r(s) = (s², s²) for s in [0, 1]

- r(u) = (sin u, sin u) for u in [0, π/2]

All three trace out the same geometric curve. The line integral ∫_C F · dr will be the same for all three parameterizations (assuming F is the same field).

Why? Because r'(t) dt, r'(s) ds, and r'(u) du all reduce to the same infinitesimal arc length element dr. The parameterization affects the speed of traversal but not the accumulation of the field.

This is conceptually important: line integrals are geometric objects. They depend on the curve and the field, not on how you choose to describe the curve.

Piecewise Smooth Curves

Not all curves are smooth. Some have corners or kinks. A piecewise smooth curve is made up of smooth segments joined end-to-end.

To integrate over a piecewise smooth curve, you integrate over each smooth piece separately and add the results:

∫C F · dr = ∫{C₁} F · dr + ∫{C₂} F · dr + ... + ∫{Cₙ} F · dr

This is linearity of integration. The curve C is the union of C₁, C₂, ..., Cₙ.

Example: Integrating around a square means integrating along four line segments and summing.

Corners don't cause problems. The derivative r'(t) might not exist at the corners, but you can integrate up to the corner on one segment and start from the corner on the next segment. The integral is well-defined.

Line Integrals in Different Coordinate Systems

So far, we've worked in Cartesian coordinates. But you can parameterize curves in polar, cylindrical, or spherical coordinates too.

In polar coordinates (r, θ), a curve might be given as r(θ). To convert to a line integral, you need to express everything in Cartesian or use the appropriate differential elements.

Example: A circle of radius a in polar coordinates is r = a, θ in [0, 2π]. In Cartesian:

x = a cos θ, y = a sin θ

dx = -a sin θ dθ, dy = a cos θ dθ

If F = (P, Q), then:

∫_C F · dr = ∫_0^{2π} (P(-a sin θ) + Q(a cos θ)) dθ

The choice of coordinate system is just a computational convenience. The line integral itself is coordinate-independent.

Applications Beyond Work

Line integrals aren't just for physics. They appear in:

Complex analysis: The integral ∫_C f(z) dz for complex-valued functions is a line integral in the complex plane. Cauchy's theorem and residue theory are all about line integrals around closed curves.

Differential geometry: Parallel transport and connections involve line integrals of 1-forms. Holonomy measures how much a vector rotates when transported around a loop.

Electromagnetism: Voltage is the line integral of the electric field. Faraday's law relates the line integral of E around a loop to the rate of change of magnetic flux through the loop.

Fluid dynamics: Circulation around a closed curve measures the total vorticity enclosed. Kelvin's circulation theorem is about line integrals.

Probability: Expected values over paths (in stochastic calculus) are essentially line integrals with respect to stochastic differentials.

The concept is general: integrate a field along a path. The applications span mathematics, physics, and engineering.

The Differential Notation dr

The notation dr deserves clarification. It's not just a symbol—it's the differential of the position vector.

If r(t) = (x(t), y(t), z(t)), then:

dr = r'(t) dt = (dx, dy, dz)

In component form:

F · dr = (P, Q, R) · (dx, dy, dz) = P dx + Q dy + R dz

You'll often see line integrals written as:

∫_C P dx + Q dy + R dz

This is the same as ∫_C F · dr. The differential notation emphasizes that you're integrating along each coordinate direction and summing.

In 2D:

∫_C P dx + Q dy

This form is common in thermodynamics and differential forms, where you're working with 1-forms (differential expressions).

Orientation Matters

The direction you traverse the curve matters. Reversing the direction reverses the sign of the line integral.

If -C denotes the curve C traversed in the opposite direction:

∫_{-C} F · dr = -∫_C F · dr

This makes physical sense. If you walk backward along a path, the work done by a force changes sign. The field projection onto the tangent reverses when the tangent reverses.

For closed curves, orientation is often specified as "counterclockwise" or "with the region on the left." This ensures consistency when applying theorems like Green's.

Relationship to Arc Length

The line integral of the constant field F = 1 (or more precisely, the integral of 1 with respect to arc length) gives the arc length of the curve:

∫_C 1 ds = ∫_a^b |r'(t)| dt = arc length

Here, ds = |r'(t)| dt is the infinitesimal arc length element. The magnitude |r'(t)| is the speed of traversal.

So arc length is a special case of a line integral. More generally:

∫_C f ds = ∫_a^b f(r(t)) |r'(t)| dt

This is a scalar line integral (integrating a scalar function with respect to arc length), as opposed to a vector line integral (integrating a vector field with respect to position).

Both types are called "line integrals," which can be confusing. The vector version (∫ F · dr) is more common in physics. The scalar version (∫ f ds) appears when you're integrating density along a curve or summing a scalar field over a path.

Green's Theorem Preview

Line integrals around closed curves are intimately connected to area integrals over the region enclosed. This connection is Green's Theorem:

∫_C F · dr = ∬_R (∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y) dA

where F = (P, Q), C is a closed curve, and R is the region it encloses.

The right side is the double integral of curl (in 2D, curl is a scalar measuring rotation). The left side is the line integral around the boundary.

This is the first of the fundamental theorems of vector calculus. It says: the circulation around the boundary equals the total curl inside. Local rotation sums to global circulation.

We'll cover Green's Theorem in detail later. For now, the key point is that line integrals don't exist in isolation—they're connected to differential operators (like curl) and to double integrals via the fundamental theorems.

Computational Tips

When computing line integrals:

- Parameterize the curve: Express r(t) explicitly. Choose a parameterization that makes r'(t) easy to compute.

- Compute r'(t): This is the tangent vector. It appears in the dot product.

- Evaluate F(r(t)): Substitute the parameterization into the field components.

- Dot product: Compute F(r(t)) · r'(t). This should simplify to a function of t.

- Integrate: ∫_a^b (result from step 4) dt. This is a single-variable integral.

- Check orientation: Make sure you're integrating in the correct direction. Reversing gives the negative.

If the field is conservative, skip all this and just compute φ(end) - φ(start).

Why Line Integrals Matter

Line integrals extend the concept of integration to paths in space. They let you accumulate vector fields along curves, which is essential for calculating work, circulation, voltage, and countless other physical quantities.

They're also the gateway to the fundamental theorems. Green's Theorem, Stokes' Theorem, and the Divergence Theorem all involve line integrals (or surface integrals, which we'll cover next) as boundary terms.

Understanding line integrals deeply—both computationally and conceptually—is necessary for understanding vector calculus as a whole. They're not just a trick for calculating work. They're a fundamental operation on vector fields, revealing structure that wouldn't be visible otherwise.

Next, we'll extend this idea from curves to surfaces: surface integrals, which let you sum a vector field over a 2D manifold in 3D space. The concept is similar, but the geometry gets richer.

Part 3 of the Vector Calculus series.

Previous: Vector Fields: Arrows at Every Point Next: Surface Integrals: Integrating Over Surfaces

Comments ()