Synthesis: Linear Algebra as the Language of Structure-Preserving Maps

We started with arrows and grids. We end with something deeper: a way of seeing.

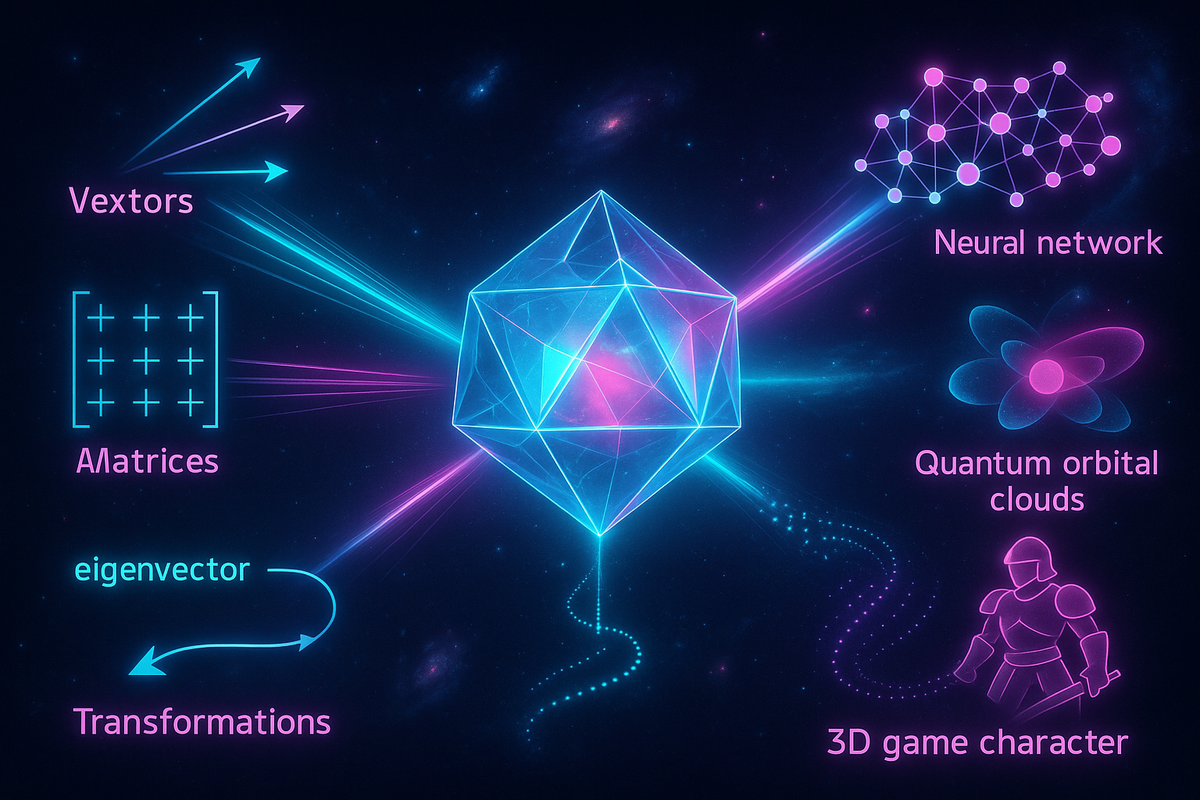

Linear algebra isn't just techniques for solving problems. It's a lens through which complex systems become simple. It's the discovery that structure matters more than substance—that the abstract patterns governing arrows in a plane are the same patterns governing quantum states, neural networks, and economic flows.

Let's synthesize what we've learned into a unified view.

The Core Abstraction

Linear algebra is built on one idea: structure-preserving transformations.

A vector space is any collection of objects you can add and scale in consistent ways. A linear transformation is a function that respects this structure—it preserves addition and scaling.

That's it. Everything else follows.

Matrices are how we represent linear transformations once we choose a basis. Determinants measure how transformations scale volume. Eigenvalues identify directions that transformations preserve. Solving systems of equations means inverting transformations.

The abstraction is powerful because it applies to anything with the right structure: arrows, polynomials, functions, quantum states. The specific objects don't matter. What matters is whether you can add them, scale them, and transform them while preserving structure.

The Three Perspectives

Throughout this series, three viewpoints have intertwined:

1. Geometric: Vectors as arrows, matrices as transformations of space, eigenvalues as invariant directions.

In two or three dimensions, you can visualize everything. A matrix rotates, stretches, shears. An eigenvector points in a direction that only scales. The determinant is the factor by which areas or volumes change.

This perspective builds intuition. When you see a matrix, you should see space being reshaped.

2. Algebraic: Systems of equations, computational procedures, algorithms.

Row reduction, matrix multiplication, determinant formulas, eigenvalue calculation. These are the tools for getting numbers out of linear algebra.

This perspective emphasizes computation. Linear algebra is practical because these operations are computable, even for millions of dimensions.

3. Abstract: Vector spaces, linear maps, structure and invariants.

The objects don't matter—any objects that behave linearly are in scope. What matters is the structure: dimension, rank, nullity, eigenvalues. These are invariants—they don't change when you change basis.

This perspective provides power. The same theorems apply whether you're studying arrows, polynomials, or infinite-dimensional function spaces.

The master sees all three simultaneously. Geometric intuition guides abstract thinking. Algebraic computation confirms abstract results. Abstract structure explains why geometric patterns generalize.

The Deep Theorem: Rank-Nullity

If you remember one theorem from linear algebra, remember this:

Rank + Nullity = Dimension of Domain

For a linear transformation T: V → W:

- Rank = dimension of image (what T can hit)

- Nullity = dimension of kernel (what T kills)

This says: every dimension of your domain goes somewhere. Either it maps to something nonzero in the image (contributing to rank) or it maps to zero (contributing to nullity).

Why It Matters:

This theorem connects abstract structure to concrete counting. It tells you:

- Whether systems of equations have solutions

- When transformations are invertible

- What information is lost under transformation

- The relationship between a matrix's row space and null space

The rank-nullity theorem is the central accounting identity of linear algebra.

Eigenvalues: The Invariant Directions

The second most important concept: eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

An eigenvector of transformation T is a direction that T merely scales: T(v) = λv. The eigenvalue λ is the scale factor.

Why They're Everywhere:

Eigenvalues reveal intrinsic properties of transformations:

- In dynamics: eigenvalues determine stability (do orbits converge or diverge?)

- In data: eigenvalues measure variance along principal components

- In quantum: eigenvalues are possible measurement outcomes

- In graphs: eigenvalues encode connectivity structure

When you find the eigenvectors and use them as a basis, the transformation becomes diagonal—just scaling along each axis. Complex transformations decompose into simple scalings.

The Spectral Theorem:

For symmetric (or Hermitian) matrices, there's always a full set of orthogonal eigenvectors. The matrix decomposes as:

A = QΛQ^T

where Q's columns are orthonormal eigenvectors and Λ is diagonal.

This is the structure theorem for symmetric transformations. It's why PCA works, why quantum observables have real eigenvalues, why vibration problems decompose into independent modes.

Change of Basis: The Sleight of Hand

Coordinates are not real. They're choices.

The same vector has different coordinates in different bases. The same transformation has different matrix representations in different bases. But the vector and transformation themselves don't change.

Why It Matters:

The right basis can transform a hard problem into a trivial one.

- In the eigenbasis, a linear transformation is just diagonal scaling.

- In the Fourier basis, convolution becomes multiplication.

- In principal components, data variance lies along axes.

Changing basis doesn't change the problem—it changes your view of the problem. The art of linear algebra is choosing coordinates that reveal structure.

Dimension: The Intrinsic Count

Dimension counts degrees of freedom.

Every basis of a vector space has the same number of elements. This number—the dimension—is an intrinsic property, independent of how you describe the space.

The Consequence:

You can't fit more independent vectors into a space than its dimension allows. You can't express all vectors as combinations of too few. Dimension is a hard constraint on what's possible.

In applications:

- A system with n unknowns and m < n equations has infinitely many solutions

- You can't reduce d-dimensional data to fewer than d numbers without information loss

- Phase space dimension determines how many initial conditions specify state

Dimension is what remains constant through all changes of perspective.

The Pattern of Applications

Every application of linear algebra follows the same template:

Step 1: Represent the problem as vectors.

Data points become vectors of features. Signals become vectors of samples. States become vectors of amplitudes. Express your problem in linear algebraic terms.

Step 2: Express relationships as matrices.

The transformation you care about—evolution, filtering, learning—becomes a matrix. The structure of the problem encodes in matrix entries.

Step 3: Apply the machinery.

- Solve systems: row reduction, inversion

- Find special directions: eigenvalue decomposition

- Optimal approximation: SVD

- Stability: eigenvalue analysis

Step 4: Interpret back in the original domain.

The abstract answer means something concrete: the system is stable, the data has three main components, the image compresses to 10% of original size.

This pattern repeats across machine learning, physics, economics, signal processing. The mathematics is the same; the interpretation varies.

What Makes It Work

Linear algebra succeeds because linearity is both common and tractable.

Common: Any smooth function looks linear near a point (Taylor's theorem). So any smooth system is approximately linear locally. And many important systems are exactly linear globally.

Tractable: Linear systems have complete theory. We can determine when solutions exist, when they're unique, how to find them efficiently. Eigenvalue decomposition works. Matrix inversion is computable.

Nonlinear systems rarely have such clean answers. But linear algebra handles the linear parts—and often, understanding the linear structure reveals what you need to know.

The Big Picture

Linear algebra is the mathematics of organized multiplicity.

Whenever you have many related quantities—features of data points, pixels of images, components of signals, dimensions of state space—linear algebra provides the tools to reason about them collectively.

It gives you:

- A language: vectors, matrices, spaces, transformations

- Operations: addition, scaling, multiplication, decomposition

- Invariants: dimension, rank, determinant, eigenvalues

- Perspectives: geometric, algebraic, abstract

These tools let you move between viewpoints, choosing the one that makes your problem clearest. The same problem might be geometric in conception, algebraic in solution, and abstract in generalization.

What's Next

Linear algebra opens doors:

To Calculus: Multivariable calculus is linear algebra applied infinitesimally. Jacobians are matrices. Hessians are matrices. The gradient is a covector. Understanding linear algebra makes multivariable calculus geometric.

To Differential Equations: Linear differential equations are linear algebra in function space. Solutions form vector spaces. Exponentials of matrices describe evolution. Eigenvalues determine stability.

To Functional Analysis: Infinite-dimensional vector spaces with topology. Hilbert spaces, Banach spaces, operators. Quantum mechanics lives here. So does Fourier analysis.

To Abstract Algebra: Vector spaces are just one kind of algebraic structure. Groups, rings, modules—all share the pattern of objects with operations satisfying axioms.

To Applications: Whatever field you work in—data science, physics, engineering, economics—linear algebra provides foundational tools.

The Unified View

Here's what linear algebra teaches:

Structure over substance. The specific objects don't matter. What matters is how they relate—what operations they support, what properties they preserve.

Coordinates are choice. The numbers depend on your perspective. The underlying objects don't. Change basis to make problems easy.

Dimension constrains. The number of independent degrees of freedom limits what's possible. Count dimensions to know what's achievable.

Transformations reveal structure. What stays fixed under transformation—eigenvectors, invariant subspaces—reveals the intrinsic character of the transformation.

Decomposition simplifies. Complex objects often decompose into simpler pieces. Find the right decomposition and complexity collapses.

These principles apply far beyond linear algebra. They're general lessons about mathematical thinking.

The Pebble

Linear algebra is the discovery that space—not physical space, but the abstract space of possibility, of states, of data—has geometry.

Once you see that neural network weights live in high-dimensional spaces, that quantum states are vectors, that economic models are matrix equations, you see linear algebra everywhere. Not because we force things into linear form, but because linear structure genuinely describes how systems behave.

Vectors and matrices aren't just calculational conveniences. They're the natural language for describing systems with many interacting parts. Linear algebra is the mathematics of complexity made tractable.

Master this subject. It's the key that unlocks modern applied mathematics.

This completes the Linear Algebra series. The mathematics of vectors, matrices, and transformations underlies machine learning, quantum mechanics, computer graphics, and much more. The same structures appear everywhere—once you learn to see them.

Part 12 of the Linear Algebra series.

Previous: Applications: Why Linear Algebra Runs the Modern World

Comments ()