Linear Regression: Fitting Lines to Data

Francis Galton was studying heredity in the 1880s. He measured parents' heights and their children's heights. And he noticed something strange.

Tall parents had tall children—but not as tall as you'd expect. If both parents were 6 feet tall, their kids averaged 5'11". Short parents had short children—but not as short. If both parents were 5 feet tall, their kids averaged 5'1".

Heights were regressing toward the mean. Extreme parents produced less extreme children.

Galton called this phenomenon "regression." And the mathematical tool he invented to model it became one of the most powerful techniques in all of statistics.

Linear regression lets you model relationships between variables. It answers questions like:

- How much does income predict voting behavior?

- Does education level correlate with lifespan?

- Can I predict sales based on advertising spend?

It's the foundation of predictive modeling, machine learning, and causal inference. Every time you see "X predicts Y" or "for every increase in X, Y changes by Z," that's regression.

This article explains what linear regression is, how it works, what it assumes, and when it breaks down.

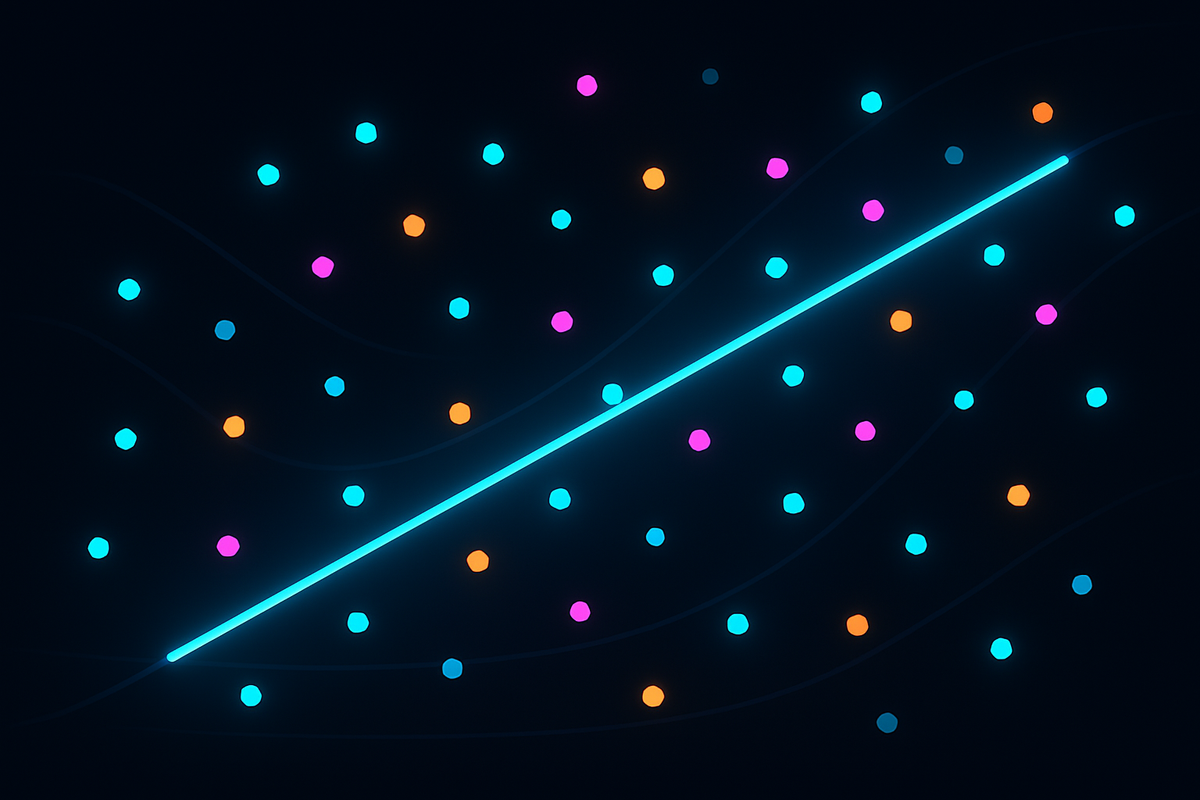

The Core Idea: Fitting a Line to Data

You have two variables: X (predictor) and Y (outcome).

You plot them. The points scatter. But there's a pattern—as X increases, Y tends to increase (or decrease).

Linear regression finds the straight line that best fits the data.

That line is your model: $Y = a + bX$

- $a$ = intercept (where the line crosses the Y-axis)

- $b$ = slope (how much Y changes per unit increase in X)

Once you have the line, you can predict Y for any value of X. Just plug X into the equation.

Example:

You measure study hours (X) and exam scores (Y) for 100 students. Regression gives you:

$$\text{Score} = 50 + 5 \times \text{Hours}$$

Interpretation: Each additional hour of study predicts a 5-point increase in exam score. A student who studies zero hours is predicted to score 50.

That's linear regression. A line. A slope. A prediction.

The Math: Ordinary Least Squares

How do you find the "best fit" line?

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) minimizes the sum of squared residuals.

Residual: The distance between an actual Y value and the predicted Y value. $\text{Residual} = Y_{\text{actual}} - Y_{\text{predicted}}$

For each data point, you calculate the residual. Square it (to make negatives positive). Sum them all.

The line that minimizes that sum is the best-fit line.

Mathematically, the slope $b$ is:

$$b = \frac{\sum (X_i - \bar{X})(Y_i - \bar{Y})}{\sum (X_i - \bar{X})^2}$$

That's the covariance of X and Y, divided by the variance of X.

The intercept $a$ is:

$$a = \bar{Y} - b\bar{X}$$

Where $\bar{X}$ and $\bar{Y}$ are the sample means.

Why least squares?

It has nice mathematical properties. It's unbiased (on average, it gives the correct answer). It's efficient (has the smallest variance among unbiased estimators). And it's computationally simple—you can solve it with linear algebra.

Interpreting the Slope: "For Every..."

The slope ($b$) tells you how much Y changes per unit increase in X.

Example: $\text{Income} = 30000 + 2000 \times \text{Years of Education}$

Interpretation: For every additional year of education, income increases by $2,000 (on average).

Critical: This is a statement about association, not necessarily causation. Education might cause higher income. Or smarter people might get more education and higher income (confounding). Or reverse causation (wealthier people can afford more schooling).

Regression tells you X and Y move together. It doesn't tell you why.

R-Squared: How Much Variance Is Explained?

A line fits the data. But how well?

R-squared ($R^2$) measures the proportion of variance in Y that's explained by X.

$$R^2 = 1 - \frac{\text{Sum of squared residuals}}{\text{Total sum of squares}}$$

Or equivalently: $R^2 = \text{correlation}^2$.

- $R^2 = 0$: X explains none of Y's variance. The line is useless.

- $R^2 = 1$: X explains all of Y's variance. Perfect prediction.

Example: You regress exam scores on study hours. $R^2 = 0.36$.

Interpretation: Study hours explain 36% of the variance in exam scores. The other 64% is unexplained—due to intelligence, prior knowledge, test anxiety, luck, etc.

Critical insight: Even low $R^2$ can be meaningful. If you're predicting a noisy outcome (human behavior, stock prices), $R^2 = 0.10$ might be impressive. In physics, $R^2 = 0.95$ is expected.

Context matters.

Assumptions: When Linear Regression Works

Linear regression makes strong assumptions. Violate them, and your results are garbage.

1. Linearity

The relationship between X and Y must be linear (or approximately so).

If Y quadruples when X doubles, a straight line won't fit. You need a nonlinear model (log transform, polynomial regression, etc.).

Check: Plot Y vs. X. Does it look roughly linear? Plot residuals vs. fitted values. Do residuals scatter randomly, or show a pattern?

2. Independence

Observations must be independent. One data point shouldn't influence another.

Violation: Time series data (today's stock price depends on yesterday's), clustered data (students within schools), repeated measures (same person measured multiple times).

Fix: Use time series models, mixed-effects models, or adjust standard errors for clustering.

3. Homoscedasticity (Constant Variance)

The variance of residuals must be constant across all values of X.

Violation: "Heteroscedasticity"—residuals fan out as X increases. Common in income data, count data, proportions.

Check: Plot residuals vs. fitted values. If the spread increases, you have heteroscedasticity.

Fix: Transform Y (log, square root), use weighted least squares, or use robust standard errors.

4. Normality of Residuals

For small samples, residuals should be normally distributed.

For large samples (n > 30), the Central Limit Theorem rescues you—normality matters less.

Check: Q-Q plot of residuals. Histogram of residuals.

Fix: If residuals are skewed, transform Y or use nonparametric methods.

5. No Multicollinearity (for Multiple Regression)

If you have multiple predictors, they shouldn't be highly correlated with each other.

Why: If X1 and X2 are perfectly correlated, you can't tell which one is "causing" Y. The model becomes unstable.

Check: Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). If VIF > 10, you have a problem.

Fix: Drop one of the correlated predictors, or use regularization (ridge regression, LASSO).

Multiple Regression: More Than One Predictor

You rarely have just one predictor. Usually, you have many.

$$Y = a + b_1 X_1 + b_2 X_2 + ... + b_k X_k$$

Each $b_i$ represents the effect of $X_i$ on Y, holding all other predictors constant.

Example: $\text{Income} = 20000 + 2000 \times \text{Education} + 500 \times \text{Experience}$

Interpretation: For every year of education, income increases by $2,000—controlling for experience. For every year of experience, income increases by $500—controlling for education.

This is powerful. You can isolate the effect of one variable while accounting for confounders.

But it's also dangerous. If you don't include the right confounders, your estimates are biased. Omitted variable bias is everywhere.

Prediction vs. Explanation

Regression serves two purposes. They're not the same.

Prediction

You want to forecast Y given X. You don't care why the relationship exists. You just want accuracy.

Example: Predicting house prices from square footage, location, bedrooms. You don't need a causal story. You just need the model to work.

Explanation

You want to understand why Y depends on X. You're making causal claims.

Example: "Does education cause higher income?" Not just "do they correlate?"

For causal inference, regression alone isn't enough. You need randomized experiments, natural experiments, instrumental variables, or causal graphs (DAGs) to identify causation.

When Regression Breaks: Non-Linearity and Outliers

Non-Linearity

If the true relationship is curved, a straight line is a bad model.

Example: Returns to education. The first year of college might increase income by $5K. The fourth year (getting the degree) might increase it by $15K. The relationship is nonlinear.

Fix: Add polynomial terms ($X^2$, $X^3$), use splines, or use nonlinear models (generalized additive models, neural networks).

Outliers and Leverage

A few extreme points can drag the regression line off course.

Outlier: A point with an unusual Y value (far from the line).

High leverage: A point with an unusual X value (far from the mean of X).

Influential point: A point that's both—it has high leverage and pulls the line toward it.

Check: Cook's distance, leverage plots, influence plots.

Fix: Investigate outliers. Are they errors? Real but rare? If real, consider robust regression (less sensitive to outliers).

Statistical Significance in Regression

Each slope coefficient has a p-value.

Null hypothesis: $b = 0$ (X has no effect on Y).

If $p < 0.05$, you reject the null. X is a "significant" predictor.

But remember all the caveats from the p-value article. Significance doesn't mean large effect. It doesn't mean causation. And with large samples, tiny effects become significant.

Always report:

- The coefficient (effect size)

- The confidence interval

- The p-value

- The $R^2$ (model fit)

Overfitting: When Your Model Memorizes Noise

Add enough predictors, and your $R^2$ goes to 1.0. Perfect fit!

Except you've overfit. Your model memorized the training data—including the noise. It won't generalize to new data.

Example: You predict stock prices using 50 variables. $R^2 = 0.99$ on historical data. But on tomorrow's data, it's useless. You fit the noise, not the signal.

The problem: More predictors always increase $R^2$, even if they're random.

The solution: Use adjusted $R^2$, which penalizes extra predictors. Or use cross-validation—test your model on held-out data.

Rule of thumb: You need at least 10-20 observations per predictor. Otherwise, you're overfitting.

Causation Requires More Than Regression

Regression detects associations. But correlation isn't causation.

Example: Ice cream sales correlate with drowning deaths. Does ice cream cause drowning?

No. Both are caused by warm weather. That's a confounding variable.

Regression on observational data can't distinguish causation from correlation. You need:

1. Randomized experiments. Randomly assign X, measure Y. Randomization breaks confounding.

2. Natural experiments. Find cases where X changes quasi-randomly (policy changes, lotteries, etc.).

3. Instrumental variables. Find a variable that affects X but not Y (except through X). Use it to isolate causation.

4. Causal DAGs. Map out the causal structure. Identify what to control for.

Without these tools, regression is descriptive, not causal.

Further Reading

- Freedman, D. A. (1991). "Statistical models and shoe leather." Sociological Methodology, 21, 291-313.

- Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2006). Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge University Press.

- Pearl, J. (2009). Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- McElreath, R. (2020). Statistical Rethinking: A Bayesian Course with Examples in R and Stan (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

This is Part 9 of the Statistics series, exploring how we extract knowledge from data. Next: "Correlation vs. Causation."

Part 8 of the Statistics series.

Previous: Type I and Type II Errors: False Positives and False Negatives Next: Correlation vs Causation: Why Ice Cream Does Not Cause Drowning

Comments ()