Living Materials: Self-Healing and Growing

Concrete cracks. It's one of the most ubiquitous construction materials on Earth, and it always cracks—from thermal expansion, settling, loading, age. Once cracked, water seeps in, corrodes the steel reinforcement, and the structure degrades. Maintenance is perpetual.

What if the concrete could heal itself?

In 2006, researchers at TU Delft introduced bacteria into concrete mix. The bacteria were spore-forming—capable of surviving for decades in a dormant state. When cracks formed and water seeped in, the bacteria woke up. They metabolized calcium lactate (included in the mix) and precipitated calcium carbonate—limestone. The cracks filled in. The concrete healed.

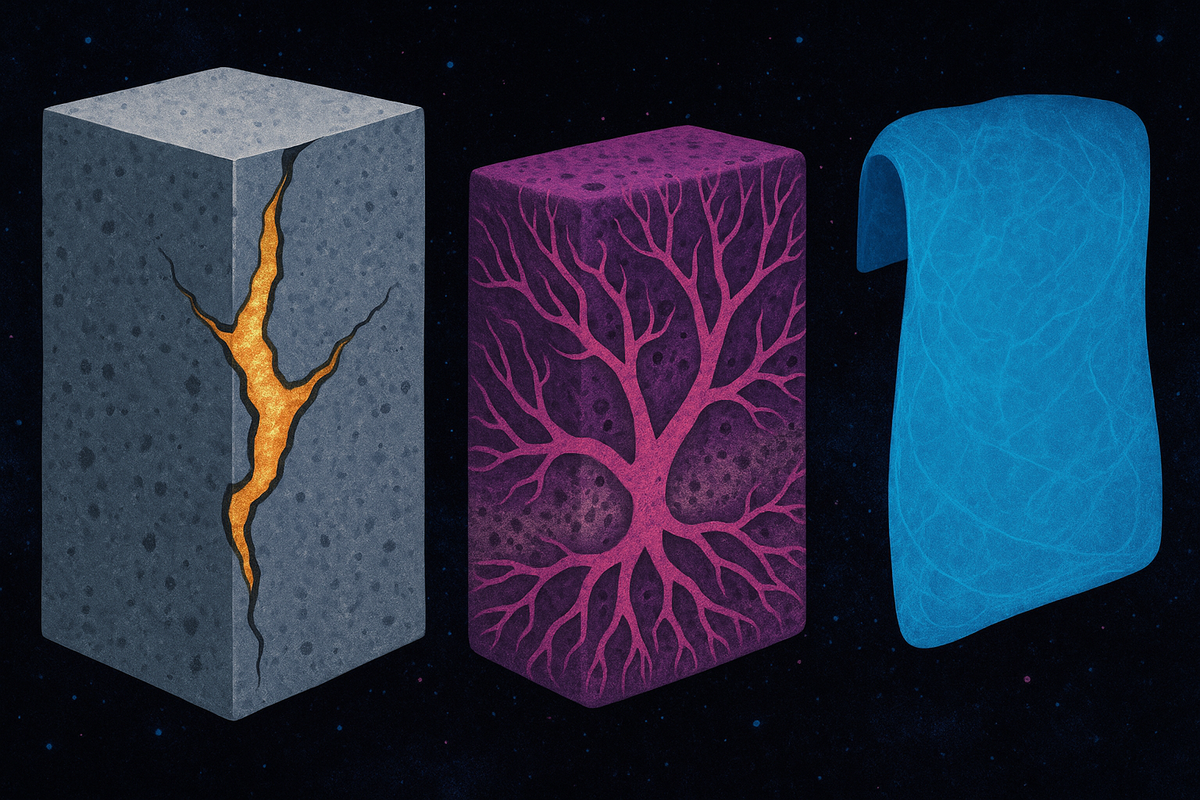

This is living material—a composite of traditional material and living cells, where the cells provide a function the material alone can't achieve. Self-healing concrete is the most famous example, but the category is expanding: living textiles, biological composites, organisms that grow into shapes.

Materials that repair themselves. Materials that grow. The line between built and biological is blurring.

Why Living?

Traditional materials are dead. Steel, concrete, plastic, glass—they don't metabolize, sense, or respond. They degrade over time but can't repair. They're manufactured in factories and arrive at their final state.

Living systems are different:

Self-repair. Cut your skin, and it heals. Break a bone, and it mends. Biological materials have built-in repair mechanisms.

Growth. Organisms grow from small to large, from simple to complex. They manufacture themselves from ambient nutrients.

Adaptation. Living systems can sense their environment and respond. Bones remodel in response to stress. Trees grow toward light.

Reproduction. Living systems can make copies of themselves. One organism becomes many.

These properties are valuable. If we could incorporate them into materials, we'd have materials that maintain themselves, adapt to conditions, and potentially manufacture themselves from cheap inputs.

Living materials are the attempt to merge the properties of life with the functions of engineering.

Self-Healing Concrete

Let's detail how bacterial concrete works.

The bacteria: Bacillus species are commonly used—they form endospores that survive harsh conditions, including the alkaline environment of concrete (pH 12-13, which kills most bacteria).

The food: Calcium lactate is mixed into the concrete. The bacteria metabolize it when activated.

The mechanism: When cracks form, water enters. The water hydrates the spores, waking the bacteria. The bacteria consume the calcium lactate and produce calcium carbonate (CaCite)—essentially, they make limestone. The CaCO₃ precipitates and fills the crack.

The result: Cracks up to 0.8 mm can be healed. The repaired concrete regains much of its structural integrity.

The technology is now commercial. Companies like Basilisk and Green Basilisk sell bacterial concrete additives. The Netherlands has test projects in infrastructure. The cost premium is falling.

Concrete has been used for over 2,000 years. This is the first fundamental improvement in how it maintains itself.

Living Building Blocks

Researchers have gone further—creating bricks and building materials that are grown, not manufactured.

Microbial bricks: At the University of Colorado Boulder, researchers developed bricks made by bacteria depositing minerals around sand particles. The bacteria (cyanobacteria, in some versions) photosynthesize, grow, and produce calcium carbonate that cements sand into a solid matrix.

These bricks are alive. Under the right conditions, they can even reproduce—a brick can be split, and each half can grow into a new brick. One brick becomes two, two become four.

The carbon footprint is potentially negative. The bacteria capture CO₂ from the atmosphere through photosynthesis. Manufacturing traditional bricks and concrete produces roughly 8% of global CO₂ emissions. Living alternatives could invert that.

Mycelium materials: Fungi, specifically the root-like network called mycelium, can be grown into materials. You provide a substrate (agricultural waste, sawdust), inoculate with fungal spores, and let the mycelium grow through it, binding it together.

The result can be dried (killing the fungus) to create a stable material—lightweight, insulating, and fully biodegradable. Companies like Ecovative produce mycelium packaging (replacing styrofoam), building panels, and even leather alternatives.

Mycelium materials aren't self-healing (the organism is dead once dried), but they're grown rather than manufactured. The production process is biological.

Grown Leather

Speaking of leather alternatives—this is one of the most commercially advanced applications.

Traditional leather requires raising animals, slaughtering them, and tanning hides with toxic chemicals. It's resource-intensive and environmentally damaging.

Mycelium leather: Bolt Threads (Mylo) and MycoWorks (Reishi) grow mycelium into sheets that can be processed like traditional leather. The texture, strength, and appearance are similar. Luxury brands including Stella McCartney, Hermès, and Adidas have used it.

Bacterial cellulose: Certain bacteria produce cellulose—a polymer similar to plant cellulose but purer. The cellulose can be grown into sheets, dried, and processed into leather-like materials. Companies like Modern Meadow (now Cultured Bio) have explored this route.

Lab-grown leather: Using animal cells, not whole animals. Grow collagen-producing cells in culture, produce the collagen matrix that constitutes leather, harvest. This is more nascent but potentially authentic leather without animals.

The leather market is enormous—over $400 billion globally. Biological alternatives are entering at the high end (fashion, luxury goods) and working down.

Engineered Living Materials (ELMs)

The academic frontier is Engineered Living Materials—composites where living cells are intentionally incorporated and remain alive, providing ongoing functions.

Examples from research:

Bacterial biofilms engineered into materials. Biofilms—communities of bacteria attached to surfaces—can be engineered to produce adhesives, enzymes, or structural proteins on demand. A surface coated with engineered biofilm could sense chemicals and respond.

Living composites with sensing. Materials that contain biosensors—the material detects conditions and changes properties. Imagine a living paint that changes color when structural stress exceeds safe limits, or a material that glows when exposed to pathogens.

Self-regenerating materials. Beyond healing cracks, materials that continuously replace worn components. Living cells embedded in the material manufacture new polymers as old ones degrade.

Responsive materials. Materials that change shape, stiffness, or permeability in response to conditions. Biology does this routinely (muscle contraction, plant movement); incorporating it into materials is harder.

Most ELMs are at laboratory scale. Manufacturing challenges, keeping cells alive over long periods, and regulatory issues limit commercialization. But the research is advancing rapidly.

Growing Structures

The most radical vision: growing buildings rather than constructing them.

This isn't as crazy as it sounds. Trees are grown structures—tall, strong, complex, and self-maintaining. A redwood is a living building material that constructed itself.

Could we do something similar intentionally?

Baubotanik (building botany) is an architectural approach that uses living trees as structural elements. Trees are planted in configurations, trained to grow into shapes, and grafted together. Over time, the living structure strengthens. Buildings that grow stronger with age, rather than weaker.

3D printing with living materials combines additive manufacturing with biological construction. Print a scaffold from a hydrogel containing cells; the cells grow and develop; the structure matures. This has been demonstrated at small scales for biological tissues (tissue engineering) and is being explored for larger structures.

Directed growth uses signals (light, chemicals, physical constraints) to guide how organisms develop. Plants can be trained to grow into specific shapes. Could we develop plants (or engineered organisms) that grow into useful structures by design?

This is speculative—no one is growing buildings today. But the logic is there. Biology knows how to construct complex structures from simple inputs. Synthetic biology is learning to direct biological construction. The intersection is growing materials.

The Challenges

Living materials face serious challenges:

Viability. Keeping cells alive over engineering timescales (years to decades) is hard. Bacteria in concrete can survive, but many cell types can't. Environmental fluctuations, nutrient limitations, and accumulation of waste products threaten long-term survival.

Control. Living systems are autonomous. They grow, adapt, and evolve—sometimes in ways designers didn't intend. Maintaining control over biological processes is fundamentally harder than controlling inert materials.

Standardization. Engineering relies on predictable materials. Steel has known properties. Living materials vary—between batches, over time, depending on conditions. Reducing this variability is essential for engineering applications.

Scale. Laboratory demonstrations are small. Scaling to infrastructure—bridges, buildings, pavements—requires solving manufacturing, logistics, and maintenance at larger scales.

Regulation. What are the safety and environmental implications of releasing living materials into the built environment? Could engineered bacteria escape and cause problems? Regulatory frameworks are nascent.

Public acceptance. People may be uncomfortable with "living" infrastructure. The psychological barrier to buildings that grow, heal, and contain organisms is real.

These challenges are being addressed, but they're not solved. Living materials are in transition from curiosity to application.

The Sustainability Argument

Traditional materials manufacturing is environmentally devastating.

Cement production generates about 8% of global CO₂ emissions. The chemistry of cement (heating limestone to release CO₂) is inherently carbon-positive.

Steel production generates another 7-8%. Smelting iron requires enormous heat, typically from fossil fuels.

Plastics are petroleum-derived. Production consumes fossil fuels; disposal creates pollution.

Living materials offer alternatives:

Carbon capture. Photosynthetic organisms (cyanobacteria, algae, plants) capture CO₂ as they grow. Materials grown by photosynthesis could be carbon-negative—pulling carbon from the atmosphere and locking it into structures.

Ambient conditions. Biology operates at room temperature and pressure. No kilns, no blast furnaces. Energy requirements are lower.

Biodegradability. Living materials can be designed to decompose safely. At end of life, they return to the biosphere rather than accumulating as waste.

Renewable inputs. The feedstocks for living materials are often agricultural waste or simple nutrients—renewable, unlike petroleum and ore.

The sustainability case is compelling. If living materials can match the performance of traditional materials at competitive cost, the environmental benefits could be transformative.

The Deeper Pattern

Living materials represent a broader trend: the convergence of biology and engineering.

For centuries, these domains were separate. Biology was nature; engineering was artifice. The distinction was ontological—living versus nonliving, natural versus artificial.

Synthetic biology erases that distinction. We engineer biology. We grow materials. We design living machines. The categories merge.

Living materials are one expression of this convergence. Cells become components. Organisms become manufacturing processes. The built environment incorporates the living.

We're not just building with biology. We're making building biological.

Further Reading

- Jonkers, H. M., et al. (2010). "Application of bacteria as self-healing agent for the development of sustainable concrete." Ecological Engineering. - Chen, A. Y., et al. (2014). "Synthesis and patterning of tunable multiscale materials with engineered cells." Nature Materials. - Heveran, C. M., et al. (2020). "Biomineralization and Successive Regeneration of Engineered Living Building Materials." Matter. - Nguyen, P. Q., et al. (2018). "Engineered Living Materials: Prospects and Challenges for Using Biological Systems to Direct the Assembly of Smart Materials." Advanced Materials.

This is Part 7 of the Synthetic Biology series. Next: "Synthesis: The Designed Biosphere."

Comments ()