Logarithmic Scales: When Numbers Span Many Orders of Magnitude

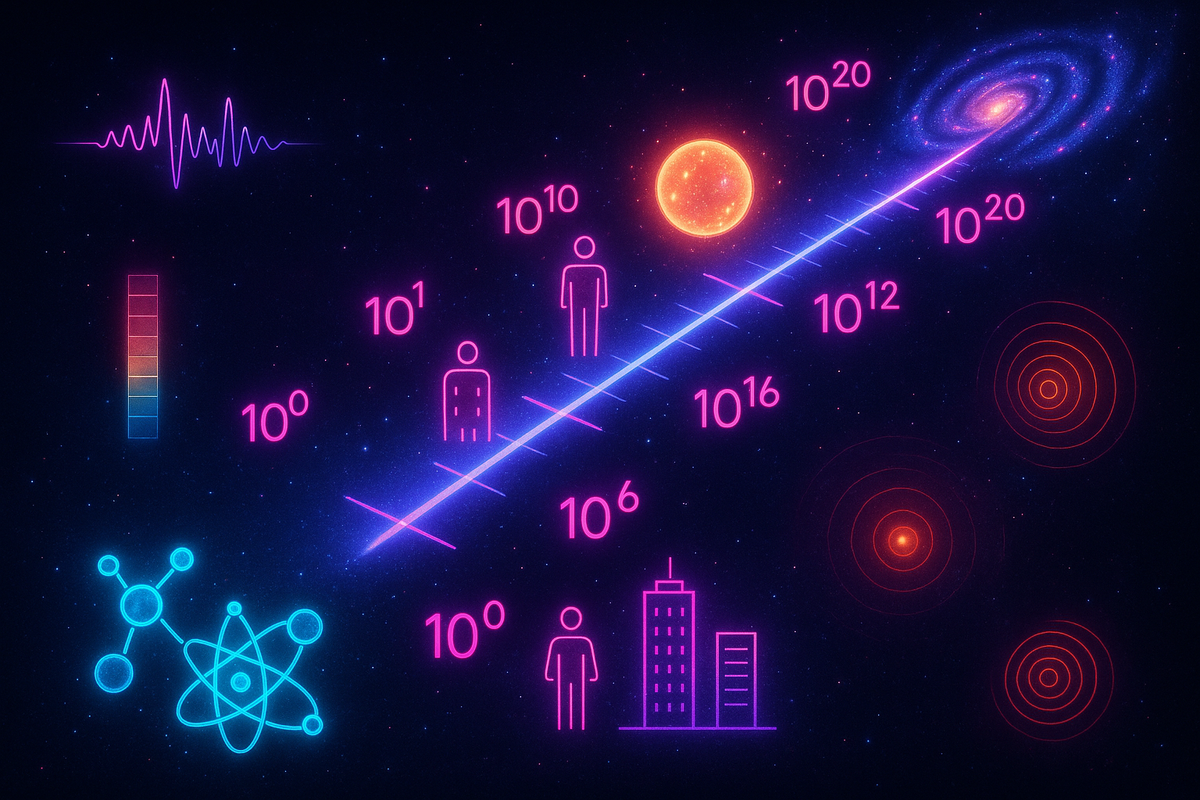

Some quantities span ranges so vast that linear scales become useless.

The loudest sound a human can tolerate is about 10 trillion times more intense than the faintest whisper we can hear. Try plotting that on a normal graph. The whisper would be an invisible speck; the jet engine would be off the page, through the wall, and somewhere in the next county.

Logarithmic scales solve this problem by measuring ratios instead of differences. Each step up the scale represents multiplication by a constant factor, not addition. This compresses enormous ranges into manageable sizes while preserving the structure of proportional relationships.

When you see decibels, pH, the Richter scale, or astronomical magnitudes, you're seeing logarithmic scales at work. They're not arbitrary conventions. They match how we actually perceive the world—and how many natural phenomena actually behave.

The Core Idea

On a linear scale, equal distances represent equal differences:

- 0 to 10 is the same distance as 90 to 100

- The gap represents +10 in both cases

On a logarithmic scale, equal distances represent equal ratios:

- 1 to 10 is the same distance as 10 to 100

- The gap represents ×10 in both cases

This means:

- Moving right by one unit multiplies by 10 (or whatever the base is)

- Moving left by one unit divides by 10

- Zero doesn't exist on the scale (you can't reach it by division)

- Negative values don't exist (you can't multiply positives to get negatives)

Decibels: The Sound Scale

Sound intensity spans an enormous range. Rather than saying "this sound is 1,000,000,000 times more intense," we use decibels:

dB = 10 × log₁₀(I / I₀)

where I₀ is the threshold of hearing (10⁻¹² W/m²).

| Sound | Intensity (W/m²) | Decibels |

|---|---|---|

| Threshold of hearing | 10⁻¹² | 0 dB |

| Whisper | 10⁻¹⁰ | 20 dB |

| Normal conversation | 10⁻⁶ | 60 dB |

| Vacuum cleaner | 10⁻⁴ | 80 dB |

| Rock concert | 10⁻¹ | 110 dB |

| Jet engine (close) | 10¹ | 130 dB |

Each 10 dB increase represents 10× more intensity. Each 20 dB increase represents 100× more intensity.

Why the factor of 10? Convention. The "bel" (named after Alexander Graham Bell) was the original unit, but it was inconveniently large, so we use decibels (tenths of a bel).

Power vs. amplitude: For voltage, pressure, or amplitude (not power/intensity), use 20 log₁₀ instead of 10 log₁₀. This is because power is proportional to amplitude squared.

pH: Measuring Acidity

The concentration of hydrogen ions in a solution can range from about 10⁻¹⁴ to 10⁰ moles per liter. That's 14 orders of magnitude.

pH compresses this:

pH = -log₁₀[H⁺]

| Solution | [H⁺] (mol/L) | pH |

|---|---|---|

| Battery acid | 10⁻¹ | 1 |

| Lemon juice | 10⁻² | 2 |

| Coffee | 10⁻⁵ | 5 |

| Pure water | 10⁻⁷ | 7 |

| Baking soda | 10⁻⁸ | 8 |

| Bleach | 10⁻¹² | 12 |

The negative sign means higher pH = lower acidity. Each pH unit represents a 10× change in hydrogen ion concentration.

pH 6 is ten times more acidic than pH 7. pH 4 is 1,000 times more acidic than pH 7.

This scale transforms a range of 10¹⁴ into a manageable 0-14 scale.

The Richter Scale: Earthquake Magnitude

Earthquake energy release varies enormously. The Richter scale (and its modern successor, moment magnitude) uses logarithms:

M = log₁₀(A / A₀)

where A is the measured amplitude and A₀ is a reference amplitude.

| Magnitude | Description | Energy (relative) |

|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | Barely felt | 1 |

| 3.0 | Minor | 32 |

| 4.0 | Light | 1,000 |

| 5.0 | Moderate | 32,000 |

| 6.0 | Strong | 1,000,000 |

| 7.0 | Major | 32,000,000 |

| 8.0 | Great | 1,000,000,000 |

Each whole number increase represents about 32× more energy released (because 10^1.5 ≈ 32).

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake (magnitude 9.0) released about 1,000 times more energy than the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake (magnitude 6.9).

Astronomical Magnitude: Stellar Brightness

Astronomers measure star brightness on a logarithmic scale that predates modern mathematics:

m = -2.5 × log₁₀(brightness / reference brightness)

Each 5-magnitude difference represents 100× difference in brightness. Each 1-magnitude difference represents about 2.5× difference.

| Object | Apparent Magnitude |

|---|---|

| Sun | -26.7 |

| Full Moon | -12.7 |

| Venus (max) | -4.6 |

| Sirius | -1.5 |

| Vega | 0.0 |

| Faintest naked-eye stars | +6 |

| Faintest Hubble objects | +31 |

The Sun is about 14 magnitudes brighter than the full Moon, which means it's 2.5¹⁴ ≈ 400,000 times brighter in apparent brightness.

The negative sign means brighter objects have lower (more negative) magnitudes—a quirk of the historical development.

Why Perception Is Logarithmic

Human perception of many quantities follows logarithmic patterns. This isn't coincidence.

Weber-Fechner Law: The perceived intensity of a stimulus is proportional to the logarithm of the actual intensity.

You can tell the difference between 1 and 2 candles easily. Between 100 and 101 candles? Nearly impossible. But 100 and 200 candles? That's noticeable—the same ratio as before.

This applies to:

- Sound: A 10 dB increase sounds "twice as loud" regardless of starting level

- Light: Perceived brightness tracks log of intensity

- Weight: You notice a 10% increase more than a fixed gram increase

- Pitch: Musical octaves are equal ratios (2:1), not equal frequency differences

Our sensory systems evolved to detect proportional changes because those often matter more for survival. A predator getting 10% closer is equally alarming whether it starts 100m or 10m away.

Log-Log Plots: When Both Axes Are Logarithmic

Sometimes both the independent and dependent variables span huge ranges. Use logarithmic scales on both axes.

Power laws become straight lines on log-log plots:

If y = axᵇ, then: log(y) = log(a) + b × log(x)

This is a linear equation in log(x) and log(y), with slope b and intercept log(a).

Applications:

- Population vs. city rank (Zipf's law)

- Earthquake frequency vs. magnitude (Gutenberg-Richter law)

- Word frequency vs. rank (linguistics)

- Species abundance distributions (ecology)

Finding a straight line on a log-log plot reveals a power law relationship. The slope tells you the exponent.

Semi-Log Plots: One Logarithmic Axis

When only one variable spans a huge range, use a semi-log plot.

Exponential growth becomes a straight line on a semi-log plot:

If y = a × eᵏˣ, then: ln(y) = ln(a) + kx

This is linear in x and ln(y), with slope k.

Applications:

- Population growth over time

- Radioactive decay curves

- Compound interest growth

- Epidemic spread

If data curves on a linear plot but straightens on a semi-log plot, it's exponential. The slope gives the growth rate.

Constructing Logarithmic Scales

To build a logarithmic scale from 1 to 1000:

- Mark 1, 10, 100, 1000 at equal intervals (these are 10⁰, 10¹, 10², 10³)

- Between 1 and 10, mark 2, 3, 4, ... at positions log₁₀(n)

- 2 is at position 0.301 (since log₁₀(2) ≈ 0.301)

- 5 is at position 0.699 (since log₁₀(5) ≈ 0.699)

- Repeat the same pattern between 10 and 100, and between 100 and 1000

The spacing compresses as you move up within each decade, then resets at the next power of 10.

This is what you see on a slide rule—a physical calculator that uses logarithmic scales to turn multiplication into addition.

Common Mistakes with Log Scales

Mistake 1: Saying "twice as many decibels"

70 dB is not "twice as loud" as 35 dB. The dB scale is already logarithmic. A 70 dB sound is 10^(70/10) / 10^(35/10) = 10^3.5 ≈ 3,162 times more intense than a 35 dB sound.

Mistake 2: Averaging on a log scale

The average of pH 2 and pH 8 is not pH 5. You need to convert to linear, average, then convert back:

- 10⁻² and 10⁻⁸ average to 5 × 10⁻³

- pH = -log(5 × 10⁻³) ≈ 2.3

Mistake 3: Forgetting zero doesn't exist

You can't plot zero on a logarithmic scale. There's no finite position for log(0) = -∞.

Mistake 4: Ignoring the base

Decibels use base 10. Natural phenomena often use base e. Binary information uses base 2. The base affects the numbers but not the fundamental behavior.

When to Use Log Scales

Use a logarithmic scale when:

- Data spans many orders of magnitude. If your smallest value is 0.001 and your largest is 1,000,000, a linear scale won't show the small values.

- Ratios matter more than differences. A 10% increase is equally significant whether you start at 10 or 10,000.

- The underlying phenomenon is multiplicative. Growth, decay, and cascading processes often scale logarithmically.

- You're looking for power laws. Log-log plots reveal power-law relationships as straight lines.

- Perception is proportional. Sound, light, and many sensory quantities follow logarithmic perception.

Don't use log scales when:

- Zero is a meaningful value

- Negative values exist

- Linear relationships are expected

- The audience won't understand it

The Deep Pattern

Logarithmic scales aren't just convenient compression. They reflect something fundamental about how quantities can relate to each other.

Linear scales assume addition is the natural operation. Add 10, add another 10, add another 10.

Logarithmic scales assume multiplication is the natural operation. Multiply by 10, multiply by 10 again, multiply again.

For many phenomena—population growth, compound interest, signal amplification, chemical concentrations—multiplication IS the natural operation. Each generation multiplies the population. Each year multiplies your investment. Each amplifier stage multiplies the signal.

When multiplication is natural, logarithms make it linear. And linear relationships are what humans understand best.

The log scale doesn't distort reality. It reveals the multiplicative structure that was there all along.

Part 6 of the Logarithms series.

Previous: Change of Base Formula: Converting Between Logarithms Next: Logarithms and Information: Why Entropy Uses Log

Comments ()