Long COVID and Cytokine Storms: When the Immune System Won't Stand Down

Here's a puzzle that emerged from the pandemic: why do some people recover from COVID-19 in days, while others—even those with mild initial infections—develop symptoms that last for months or years?

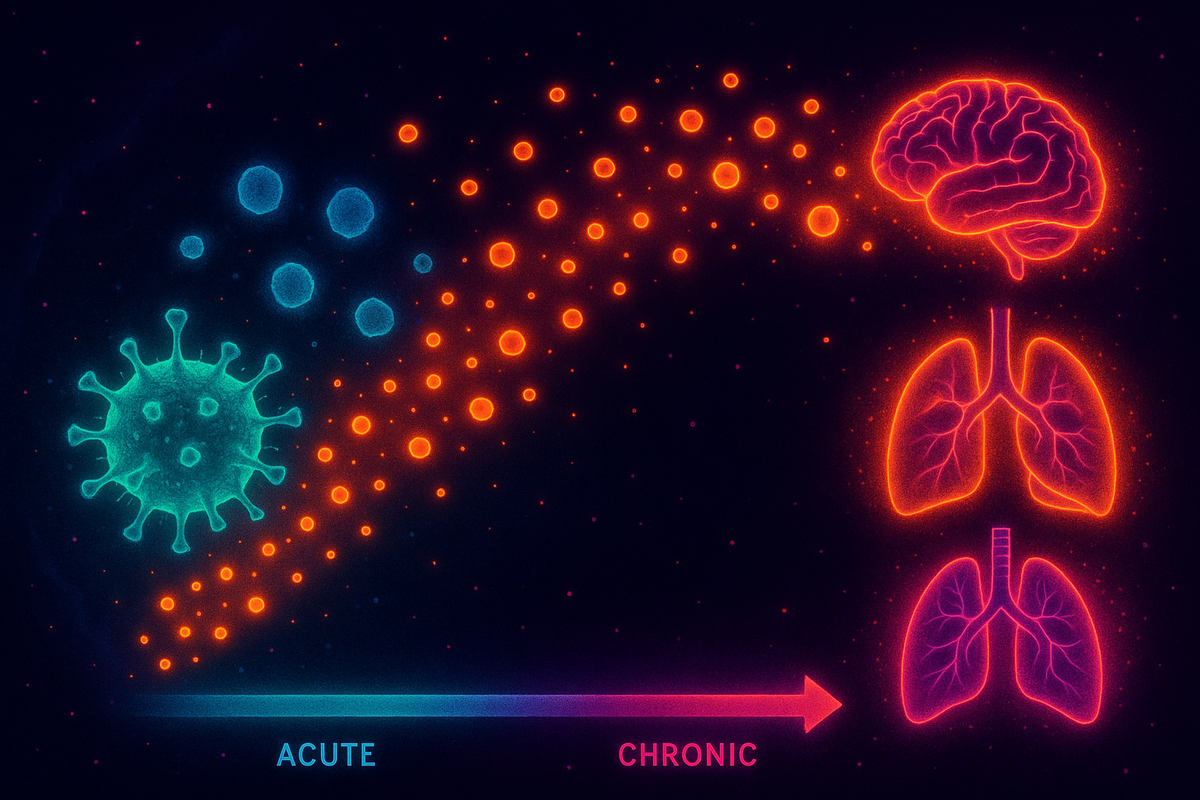

The answer appears to be immune dysregulation. Not infection persisting, but the immune response itself going wrong. The alarm keeps ringing long after the fire is out.

Long COVID is, at least in part, a story about what happens when the immune system can't return to baseline. And that story connects to a broader pattern of post-infectious syndromes, autoimmunity, and chronic inflammation that medicine is only beginning to understand.

The Cytokine Storm

Let's start with the acute crisis: the cytokine storm.

When SARS-CoV-2 infects cells, the immune system responds with inflammation. Infected cells release signaling molecules called cytokines that recruit immune cells, trigger fever, and coordinate the response. This is normal and necessary.

But in some COVID patients—particularly those with severe disease—the cytokine response spirals out of control. Pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and others) flood the bloodstream. The immune system attacks not just infected cells but healthy tissue. Lungs fill with fluid. Organs fail. Blood clots form. The immune response becomes more dangerous than the virus itself.

This is cytokine release syndrome (CRS), sometimes called a cytokine storm. The same phenomenon we saw in CAR-T therapy—except here it's triggered by infection rather than engineered cells.

The patients who died from COVID weren't typically killed by the virus directly. They were killed by their own immune response. The patients who survived severe COVID often did so because clinicians learned to suppress the immune storm with steroids, IL-6 blockers, and other immunomodulators.

The immune system is supposed to be proportionate. In cytokine storm, it loses all proportion.

What Is Long COVID?

Long COVID—formally called post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC)—is defined as symptoms persisting more than 4-12 weeks after initial infection.

The symptom list is long and strange: - Fatigue (often severe, debilitating) - Cognitive dysfunction ("brain fog"—difficulty concentrating, memory problems) - Post-exertional malaise (symptoms worsen after physical or mental effort) - Shortness of breath - Heart palpitations - Headaches - Sleep disturbances - Anxiety and depression - Loss of taste and smell - Joint and muscle pain

Some patients recover over months. Others remain symptomatic for years. Estimates suggest 10-30% of COVID cases develop some form of long COVID, though definitions and severity vary widely.

The pattern is familiar. Long COVID resembles other post-infectious syndromes: chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), post-treatment Lyme syndrome, post-viral syndromes following Epstein-Barr or influenza. It also overlaps with dysautonomia syndromes like POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome), which has spiked since the pandemic.

The immune system is implicated in all of these. The question is: implicated how?

The Hypotheses

Several mechanisms may explain long COVID. They're not mutually exclusive—different patients may have different underlying processes, and multiple mechanisms may operate in the same patient.

Viral persistence. The virus may not be fully cleared. SARS-CoV-2 RNA and proteins have been detected in tissues (gut, brain, fat, lymph nodes) months after infection. If viral fragments persist, they could drive ongoing immune activation. The immune system keeps fighting because there's still something to fight.

Autoimmunity. The immune response to the virus may generate autoantibodies—antibodies that attack the body's own proteins. Several studies have found elevated autoantibodies in long COVID patients, targeting tissues like the nervous system, blood vessels, and cardiac cells. The virus may have triggered an autoimmune process that continues after the virus is gone.

Immune dysregulation. Even without viral persistence or autoantibodies, the immune system may be stuck in a dysregulated state—chronically activated, unable to return to homeostasis. Elevated inflammatory markers (cytokines, monocytes) have been found in long COVID patients months after infection.

Microbiome disruption. COVID affects the gut microbiome. Alterations in gut bacteria have been associated with long COVID symptoms and duration. The gut-immune-brain axis may be disrupted.

Vascular damage. COVID causes endothelial damage and microclotting. Tiny clots may persist, impairing blood flow to tissues. Some researchers have found elevated markers of clotting and microclot burden in long COVID patients.

Nervous system effects. SARS-CoV-2 can affect the nervous system directly (neuroinvasion) or indirectly (through inflammation). Damage to the autonomic nervous system could explain symptoms like heart rate dysregulation, fatigue, and brain fog.

The honest answer: we don't fully know. Long COVID is likely a collection of conditions with different underlying mechanisms, grouped together because they share an inciting event (COVID infection) and a temporal pattern (persistence after acute illness).

The Immune Signature

What makes the immune connection compelling is that long COVID patients show measurable immune abnormalities.

Studies have found: - Elevated cytokines: Pro-inflammatory cytokines remain elevated months after infection in some long COVID patients, suggesting ongoing immune activation. - T cell exhaustion: T cells show markers of chronic activation and exhaustion, as if they've been fighting for too long and are worn out. - Monocyte abnormalities: Monocytes (immune cells involved in inflammation) show altered gene expression consistent with chronic inflammation. - Autoantibodies: Antibodies targeting neural tissue, G-protein coupled receptors, and other self-proteins are elevated in subsets of patients. - Complement activation: The complement system (part of innate immunity) shows signs of ongoing activation.

The picture is one of an immune system that didn't stand down. The acute infection resolved, but the immune response kept going—at lower intensity than a cytokine storm, but enough to cause symptoms.

This connects to a broader concept: immune resolution. For the immune system to function properly, it must not only activate in response to threat but also deactivate when the threat is cleared. Chronic inflammatory diseases often involve failure of resolution—the off switch doesn't work.

Long COVID may be, in part, a resolution failure.

The Connection to ME/CFS

Long COVID has brought unprecedented attention to a condition that was long dismissed: myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

ME/CFS shares core features with long COVID: - Profound fatigue not relieved by rest - Post-exertional malaise (the hallmark symptom—patients crash after activity) - Cognitive dysfunction - Unrefreshing sleep - Autonomic symptoms

Many cases of ME/CFS begin after viral infections (Epstein-Barr, enteroviruses, influenza). The pattern is similar: acute infection, apparent recovery, then gradual onset of chronic symptoms.

For decades, ME/CFS was dismissed as psychological, malingering, or "medically unexplained." Patients were told to exercise more, think positively, stop being anxious. This advice often made them worse.

The influx of long COVID patients—millions of them, including healthcare workers, athletes, and people with no psychiatric history—has forced a reconsideration. If long COVID is real (it is), and if it resembles ME/CFS (it does), then ME/CFS probably reflects similar biological processes.

Research into long COVID is producing insights that may apply to ME/CFS and other post-viral syndromes. The science of immune dysregulation is finally getting the attention it deserves.

Treatment Approaches

There is no proven cure for long COVID. Treatment is currently symptomatic and supportive.

What seems to help some patients: - Pacing (careful management of activity to avoid post-exertional crashes) - Low-dose naltrexone (an immune modulator that some find helpful) - Antihistamines (for patients with mast cell activation symptoms) - Beta-blockers (for POTS and heart rate issues) - Cognitive rehabilitation (for brain fog) - Physical therapy (carefully graduated, respecting post-exertional malaise)

What's being tested: - Antivirals (Paxlovid, others) to clear any persistent virus - Immunomodulators to calm ongoing inflammation - Microbiome interventions - Anticoagulants for microclotting - Hyperbaric oxygen therapy

What doesn't help (and may harm): - Aggressive exercise programs (can trigger crashes) - Dismissing symptoms as anxiety (delays treatment and alienates patients) - "Pushing through" (the opposite of what these patients need)

The honest state of treatment: we're experimenting. Different patients respond to different approaches. The heterogeneity of long COVID suggests it's multiple conditions under one name, requiring personalized treatment.

The Bigger Picture

Long COVID reveals something important: the immune system is not binary. It doesn't just turn on and off. It can get stuck in intermediate states—not acutely inflamed, not fully resolved, but chronically dysregulated.

These intermediate states may explain a range of chronic conditions: ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, post-treatment Lyme, Gulf War illness, and others that have been poorly understood and often dismissed.

The pattern: 1. An initial insult (infection, trauma, toxin) activates the immune system 2. The acute phase resolves, but the immune system doesn't fully reset 3. Chronic low-grade immune dysregulation produces ongoing symptoms 4. Standard tests may be normal because we're not measuring the right things

We've been looking for pathogens when we should have been looking at immune states. The pathogen may be gone. The immune dysfunction persists.

This reframing has implications for treatment. Instead of searching for a hidden infection to eradicate, we should focus on helping the immune system resolve—to complete the off-ramp it got stuck on.

Long COVID is a tragedy for millions of patients. But it's also an opportunity: a chance to finally understand the biology of post-infectious syndromes and chronic immune dysregulation. The research infrastructure and funding mobilized for long COVID may crack problems that have been neglected for decades.

Further Reading

- Davis, H. E. et al. (2023). "Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations." Nature Reviews Microbiology. - Al-Aly, Z. et al. (2022). "Long COVID science, research and policy." Nature Medicine. - Komaroff, A. L. & Bateman, L. (2021). "Will COVID-19 Lead to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome?" Frontiers in Medicine.

This is Part 7 of the Immunology Renaissance series. Next: "The Language of Immunity: A Synthesis."

Comments ()