Matrix Multiplication: Why the Rows and Columns Dance

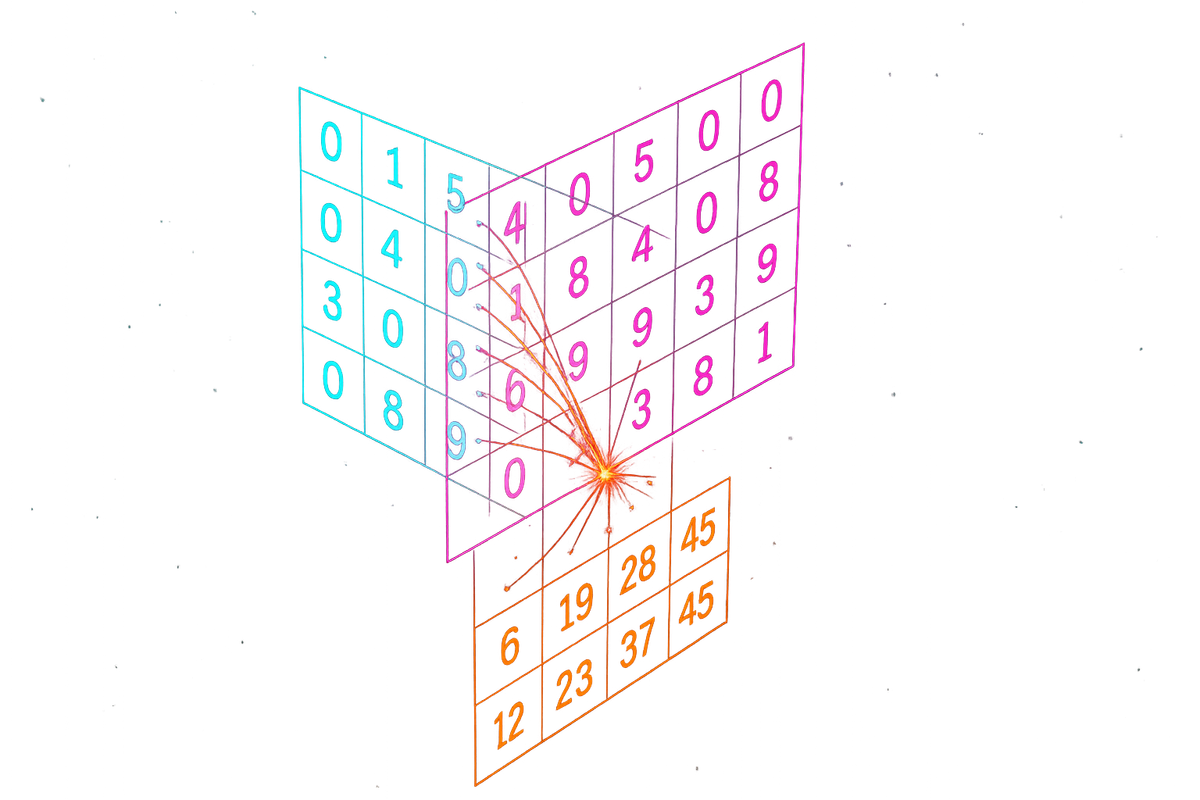

You learned the rule in school: multiply rows by columns, add the products.

You probably wondered why.

Here's why: matrix multiplication is composition of transformations. When you multiply matrices A and B, you're asking: what single transformation has the same effect as doing B first, then A?

The rows-times-columns rule isn't arbitrary. It's what makes composition work. And once you see that, matrix multiplication becomes obvious.

The Key Insight: Composition

Let's say matrix B transforms space somehow—rotates it, stretches it, whatever. Then matrix A transforms it again.

The result is a new transformation that combines both effects.

You want a single matrix C = AB that does in one step what B and A do in two steps.

For any vector v:

Cv = A(Bv)

Apply B first (transform v to Bv). Then apply A (transform Bv to A(Bv)).

The matrix C = AB captures the combined effect.

Why Rows Times Columns

Let's work it out.

B is a 2×2 matrix with columns b₁ and b₂ (where each column is a 2D vector).

When B acts on basis vector ê₁ = (1,0), it produces b₁. When B acts on ê₂ = (0,1), it produces b₂.

Now A acts on these transformed basis vectors:

- A(b₁) = first column of AB

- A(b₂) = second column of AB

How do you compute A(b₁)?

b₁ is a vector. A acts on it by taking a linear combination of A's columns, weighted by b₁'s components.

If A has columns a₁ and a₂, and b₁ = (b₁₁, b₂₁), then:

A(b₁) = b₁₁ · a₁ + b₂₁ · a₂

The result is the first column of AB.

Work through the arithmetic and you get: the (i,j) entry of AB is the dot product of row i of A with column j of B.

That's the rule. It follows from requiring that AB represent "do B, then do A."

The Mechanics

For 2×2 matrices:

| a b | | e f | | ae+bg af+bh |

| c d | × | g h | = | ce+dg cf+dh |

Each entry is a dot product:

- (1,1) entry: row 1 of first × column 1 of second = ae + bg

- (1,2) entry: row 1 of first × column 2 of second = af + bh

- (2,1) entry: row 2 of first × column 1 of second = ce + dg

- (2,2) entry: row 2 of first × column 2 of second = cf + dh

The pattern generalizes:

Entry (i,j) of AB = dot product of row i of A with column j of B.

Dimensions Must Match

For AB to make sense, the number of columns in A must equal the number of rows in B.

If A is m×n and B is n×p, then AB is m×p.

A transforms n-dimensional vectors into m-dimensional vectors. B transforms p-dimensional vectors into n-dimensional vectors.

The composition AB transforms p-dimensional vectors into m-dimensional vectors. First B maps to n dimensions, then A maps to m dimensions. The intermediate n-dimensional space is where they connect.

If the dimensions don't match, composition doesn't make sense, and multiplication isn't defined.

Order Matters: AB ≠ BA

Matrix multiplication is not commutative. AB ≠ BA in general.

Geometrically: rotate then scale is different from scale then rotate.

Example: Let A be a 90° counterclockwise rotation and B be a horizontal stretch by factor 2.

If you stretch first then rotate: a horizontal line becomes a long horizontal line, then rotates to become a long vertical line.

If you rotate first then stretch: a horizontal line becomes a vertical line, then the horizontal stretch has no effect (vertical lines stay vertical under horizontal stretching).

Different results. Order matters.

This is why we're careful to say AB means "apply B first, then A." Read right to left, like function composition: (A ∘ B)(v) = A(B(v)).

Associativity: (AB)C = A(BC)

While multiplication isn't commutative, it is associative.

(AB)C = A(BC)

Geometrically: "do C, then B, then A" can be computed as:

- "do C, then (do B then A)" or

- "(do C then B), then A"

Same final result.

This means you can group multiplications however you want. For large matrix products, smart grouping can reduce computation.

The Identity Matrix

The identity matrix I is the "do nothing" transformation.

| 1 0 |

| 0 1 |

For any matrix A: AI = A and IA = A.

Multiplying by I leaves the transformation unchanged. It's the multiplicative identity, just like 1 for numbers.

Matrix Powers

If A is a square matrix, you can multiply it by itself:

A² = AA A³ = AAA

And so on.

Geometrically: A² is the transformation A applied twice. If A rotates by 30°, A² rotates by 60°. If A scales by 2, A² scales by 4.

This leads to matrix exponentiation, which is used in physics (time evolution) and graph theory (counting paths).

Inverse Matrices

If A is invertible, there exists A⁻¹ such that:

AA⁻¹ = A⁻¹A = I

The inverse undoes the transformation. If A rotates 30° clockwise, A⁻¹ rotates 30° counterclockwise.

Not all matrices have inverses. If A collapses dimensions (like a projection), information is lost and can't be recovered.

The key test: if det(A) ≠ 0, then A is invertible.

Why This Matters

Solving equations: To solve Ax = b, multiply both sides by A⁻¹: x = A⁻¹b.

Changing coordinates: If P changes from one basis to another, and A represents a transformation in the old basis, then P⁻¹AP represents the same transformation in the new basis.

Markov chains: State transition matrices multiply to give multi-step transition probabilities.

Neural networks: Each layer is a matrix multiplication followed by a nonlinearity. The network is a long chain of matrix multiplications.

Computer graphics: Model, view, and projection matrices multiply to transform 3D objects to 2D screen coordinates.

The Computational Perspective

Matrix multiplication is expensive but parallelizable.

Multiplying two n×n matrices naively requires n³ multiplications. For large n, that's a lot.

But the operations are independent—they can run in parallel. This is why GPUs (designed for parallel computation) are so good at machine learning. Neural network training is mostly matrix multiplication.

Clever algorithms (like Strassen's) reduce the exponent below 3, but for practical sizes, optimized naive multiplication on GPUs wins.

Examples That Build Intuition

Rotation then Rotation

Rotate by 30°, then rotate by 45°. Combined effect: rotate by 75°.

If R(θ) is the rotation matrix for angle θ, then R(30°)R(45°) = R(75°).

Rotation matrices compose by adding angles. The arithmetic of matrix multiplication makes this work.

Scale then Rotate vs Rotate then Scale

Scale by 2 horizontally, then rotate 90°: a unit square becomes a 2×1 rectangle lying horizontally, then rotates to become a 2×1 rectangle standing vertically.

Rotate 90°, then scale by 2 horizontally: a unit square rotates to stay a unit square (different orientation), then stretches horizontally to become a 2×1 rectangle lying horizontally.

Different final shapes. Order matters.

Projection Destroys Information

Project onto the x-axis, then onto the y-axis: everything becomes the origin.

The composition of two perpendicular projections is the zero matrix.

The Pattern

Matrix multiplication encodes something deep: how transformations compose.

When you chain transformations, you're building complex operations from simple ones. The rule for combining them—rows times columns—isn't a random algorithm. It's the unique rule that makes composition work correctly.

The geometry demands the arithmetic. Not the other way around.

Looking Ahead

Matrix multiplication lets you compose transformations. But some properties of a transformation are fundamental—they don't change when you compose with other transformations (under certain conditions).

The determinant measures volume scaling. Eigenvalues identify special directions that only scale, never rotate.

These are the invariants of linear algebra—the properties that persist through composition.

Determinants are next.

This is Part 4 of the Linear Algebra series. Next: "Determinants: The Volume-Scaling Factor of Matrices."

Part 4 of the Linear Algebra series.

Previous: Matrices: Arrays That Transform Vectors Next: Determinants: The Volume-Scaling Factor of Matrices

Comments ()