Membrane Potentials: Free Energy Across the Cell

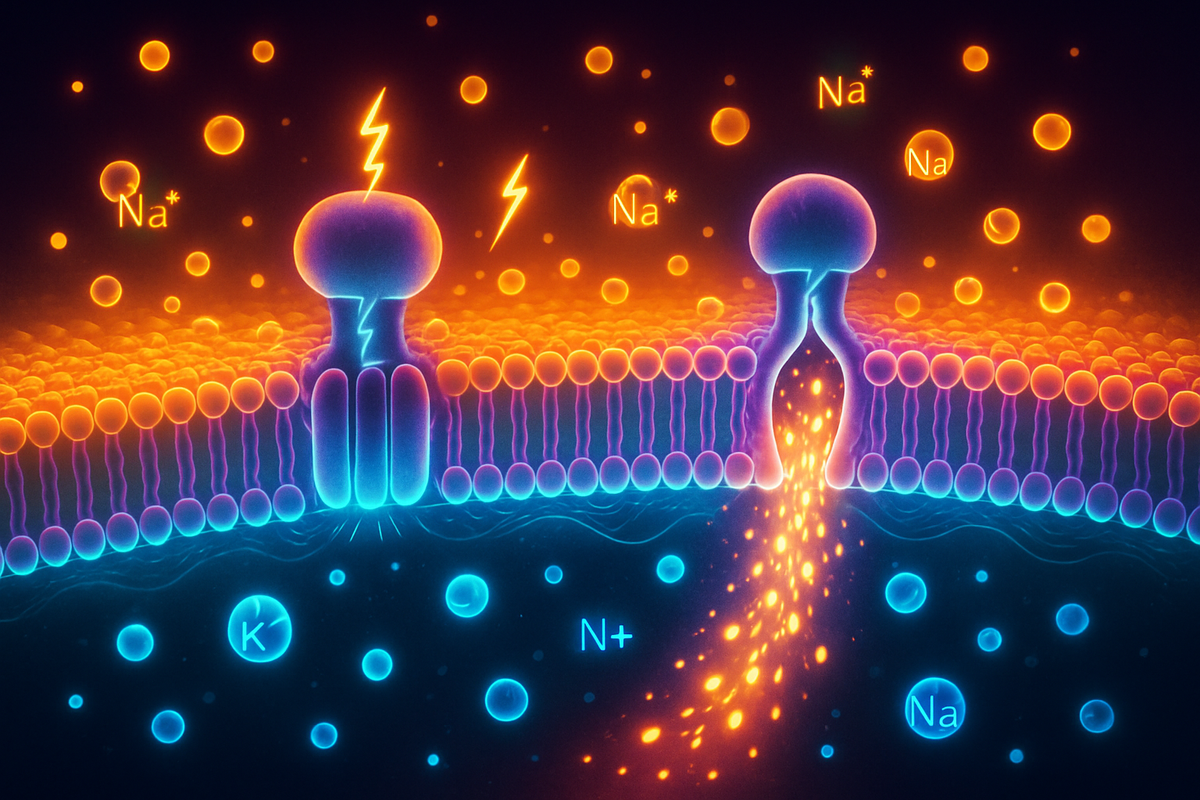

Every neuron maintains a voltage across its membrane—about -70 mV inside relative to outside. This isn't a trivial detail. It's a thermodynamic battery, charged by burning ATP and discharged to send signals.

Membrane potentials store free energy in ion gradients. Sodium is concentrated outside, potassium inside. This arrangement is unfavorable—it costs energy to maintain. But that stored energy powers everything from nerve impulses to muscle contraction to ATP synthesis itself.

Understanding membrane potentials through Gibbs free energy reveals how cells build and use electrochemical batteries, and why your nervous system runs on carefully maintained disequilibrium.

Electrochemical Potential

An ion crossing a membrane experiences two forces:

1. Chemical gradient: Concentration difference (ions diffuse from high to low concentration) 2. Electrical gradient: Voltage difference (charged ions move in electric fields)

The total electrochemical potential combines both:

Δμ = RT ln([X]_out/[X]_in) + zFΔψ

Where: - [X]_out, [X]_in = ion concentrations outside and inside - z = ion charge - F = Faraday constant (96,485 C/mol) - Δψ = membrane potential (voltage across membrane)

This Δμ is the free energy change for moving one mole of ion X across the membrane.

The pebble: Cells don't just have chemical gradients. They have electrochemical gradients—concentration and voltage combined into a single free energy measure.

The Nernst Equation

At equilibrium for a single ion, the chemical and electrical gradients balance:

RT ln([X]_out/[X]_in) = -zFΔψ

Solving for the equilibrium potential:

E_X = (RT/zF) ln([X]_out/[X]_in)

At 37°C: E_X = (61.5 mV/z) log([X]_out/[X]_in)

For typical neurons: - K⁺: [in] = 140 mM, [out] = 5 mM → E_K = -89 mV - Na⁺: [in] = 12 mM, [out] = 140 mM → E_Na = +67 mV - Cl⁻: [in] = 4 mM, [out] = 120 mM → E_Cl = -89 mV

Each ion has its own equilibrium potential. If the membrane were permeable only to K⁺, it would rest at -89 mV. Only to Na⁺: +67 mV.

The actual resting potential (-70 mV) reflects a weighted average of these equilibria.

Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz Equation

Real membranes are permeable to multiple ions. The GHK equation accounts for all permeant ions:

V_m = (RT/F) ln[(P_K[K⁺]_out + P_Na[Na⁺]_out + P_Cl[Cl⁻]_in) / (P_K[K⁺]_in + P_Na[Na⁺]_in + P_Cl[Cl⁻]_out)]

Where P_X is the permeability to ion X.

At rest, P_K >> P_Na >> P_Cl. Potassium dominates, so V_m ≈ -70 mV, close to E_K.

During an action potential, P_Na suddenly increases. V_m swings toward E_Na (+67 mV). Then P_K increases, returning V_m to rest.

The action potential is a free energy release—the ion gradients discharge through the membrane.

Free Energy Stored in Gradients

How much energy is stored in a concentration gradient?

For one mole of K⁺ at resting potential: ΔG = RT ln([K⁺]_out/[K⁺]_in) + zF(V_out - V_in) ΔG = (8.314)(310) ln(5/140) + (1)(96485)(-0.070 - 0) ΔG = -8.7 kJ/mol - 6.8 kJ/mol = -15.5 kJ/mol

Potassium wants to leave the cell (ΔG < 0), but only slightly because the voltage almost balances the concentration gradient.

For Na⁺: ΔG = RT ln([Na⁺]_in/[Na⁺]_out) + zF(V_in - V_out) ΔG = (8.314)(310) ln(12/140) + (1)(96485)(+0.070) ΔG = -6.3 kJ/mol + 6.8 kJ/mol = +0.5 kJ/mol...

Wait, let me recalculate for Na⁺ flowing inward: ΔG = RT ln([Na⁺]_out/[Na⁺]_in) + zF(V_in - V_out) ΔG = +6.3 kJ/mol + (-6.8 kJ/mol) = -0.5 kJ/mol

Actually, considering both terms properly for Na⁺ entering: The concentration gradient favors entry: ΔG_conc = -6.3 kJ/mol The electrical gradient favors entry: ΔG_elec = -6.8 kJ/mol Total: ΔG = -13.1 kJ/mol

Sodium strongly wants to enter. This is why action potentials are explosive—Na⁺ rushes down a steep electrochemical gradient.

The Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase: Charging the Battery

The ion gradients don't maintain themselves. Left alone, Na⁺ would leak in, K⁺ would leak out, and the membrane potential would dissipate.

The Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase (sodium-potassium pump) actively maintains the gradients:

3 Na⁺_in + 2 K⁺_out + ATP → 3 Na⁺_out + 2 K⁺_in + ADP + Pi

It pumps Na⁺ out against its gradient (unfavorable) and K⁺ in against its gradient (unfavorable). ATP hydrolysis provides the driving force.

Energy accounting: - Pumping 3 Na⁺ out: ΔG ≈ +40 kJ - Pumping 2 K⁺ in: ΔG ≈ +3 kJ - Net transport: ΔG ≈ +43 kJ - ATP hydrolysis: ΔG ≈ -50 kJ - Overall: ΔG ≈ -7 kJ (favorable, reaction proceeds)

The pump converts chemical energy (ATP) to electrochemical energy (ion gradients). It's a molecular turbine, charging the cellular battery.

The pebble: Your brain runs on ATP, but not directly. ATP charges ion gradients; ion gradients fire neurons. It's a two-stage energy conversion.

The Action Potential: Discharging the Battery

An action potential is a controlled discharge:

1. Depolarization: Na⁺ channels open. Na⁺ rushes in (downhill electrochemically). Membrane depolarizes toward E_Na.

2. Repolarization: K⁺ channels open. K⁺ rushes out (downhill electrochemically). Membrane repolarizes toward E_K.

3. Recovery: Pumps restore gradients using ATP.

Each action potential moves ~10^6 Na⁺ and K⁺ ions. This sounds like a lot, but cellular ion pools are ~10^11-10^12 ions. Thousands of action potentials can fire before gradients significantly deplete.

The energetic cost: ~10^7-10^8 ATP per action potential for the Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase to restore gradients. This is why neurons are metabolically expensive—they're constantly recharging.

Mitochondria: The Proton Gradient

Mitochondria use the same principle in reverse.

The electron transport chain pumps protons (H⁺) from the matrix to the intermembrane space, creating: - Concentration gradient: [H⁺]_out > [H⁺]_in - Voltage: ~-180 mV (matrix negative)

This proton-motive force stores free energy:

ΔG = RT ln([H⁺]_out/[H⁺]_in) + zFΔψ ΔG ≈ 2.3RT(ΔpH) + FΔψ ΔG ≈ 5.9 kJ/mol (pH gradient) + 17.4 kJ/mol (voltage) ΔG ≈ 23 kJ/mol per proton

ATP synthase lets protons flow back down their gradient, using the free energy to synthesize ATP:

~3 H⁺ flowing down + ADP + Pi → ATP + ~3 H⁺ in matrix

The proton gradient is the intermediate currency between electron transport and ATP synthesis.

The pebble: Mitochondria are proton batteries. The electron transport chain charges them; ATP synthase discharges them. Every breath you take is building and spending proton gradients.

Signal Propagation and Cable Properties

Ion gradients don't just trigger action potentials—they propagate them.

The action potential at one point depolarizes adjacent membrane (passive spread). This triggers voltage-gated channels at the next point. The signal propagates without decrement.

Cable theory describes passive spread: - Length constant (λ): How far voltage spreads before decaying to 1/e (~37%). Larger axons have larger λ. - Time constant (τ): How fast voltage responds. Determined by membrane capacitance and resistance.

Myelination increases λ dramatically by reducing capacitance. Signals jump between nodes of Ranvier (saltatory conduction), faster and more energy-efficient.

All of this is free energy in action—gradients charging and discharging along the cable of the axon.

Chloride and Inhibition

Chloride (Cl⁻) is often ignored, but it's crucial for inhibition.

E_Cl ≈ -89 mV in mature neurons. GABA_A receptors are Cl⁻ channels. When GABA binds, Cl⁻ flows in (at typical V_m), hyperpolarizing the membrane toward E_Cl.

This is inhibition—moving the membrane away from action potential threshold.

The free energy view: Cl⁻ is near equilibrium at rest. Opening Cl⁻ channels "clamps" the membrane near E_Cl, opposing excitation. The gradient stores minimal energy but provides powerful stabilization.

Calcium: The Signaling Ion

Ca²⁺ has the steepest gradient: - [Ca²⁺]_in ≈ 100 nM - [Ca²⁺]_out ≈ 2 mM - Ratio: ~20,000-fold!

E_Ca ≈ +130 mV

The electrochemical gradient for Ca²⁺ entry is enormous. When Ca²⁺ channels open, Ca²⁺ floods in, triggering: - Neurotransmitter release - Muscle contraction - Enzyme activation - Gene expression

Maintaining the Ca²⁺ gradient is energetically expensive. Multiple pumps and exchangers keep cytoplasmic Ca²⁺ low. But the payoff is a powerful, tightly controlled signal.

The pebble: Calcium is the cell's ultimate contingency signal. The gradient is so steep that any leak means something important happened.

Pathology of Gradient Collapse

When ion gradients fail:

Ischemia (stroke): ATP depletion stops pumps. Gradients collapse. Glutamate accumulates, Ca²⁺ floods in, neurons die. This "excitotoxicity" is free energy catastrophe.

Cardiac arrhythmia: Altered K⁺ gradients change action potential shape. Conduction disturbances cause irregular heartbeat.

Epilepsy: Disrupted inhibition (Cl⁻ gradients, GABA systems) allows runaway excitation.

Mitochondrial disease: Proton gradients fail. ATP synthesis collapses. Tissues with high energy demands (brain, muscle) fail first.

Membrane potential diseases are fundamentally free energy diseases.

Summary

Membrane potentials are electrochemical free energy storage:

- Concentration and voltage combine into electrochemical potential - The Nernst equation gives equilibrium for single ions - GHK equation handles multiple ions - Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase charges the battery; action potentials discharge it - Mitochondrial proton gradients power ATP synthesis - Calcium gradients provide signaling power

The pebble: Your thoughts are ion gradients discharging. Consciousness is the sound of free energy cascading through neural networks, paid for in ATP, written in millivolts.

Further Reading

- Hille, B. (2001). Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sinauer Associates. - Nicholls, D. G. & Ferguson, S. J. (2013). Bioenergetics 4. Academic Press.

This is Part 11 of the Gibbs Free Energy series. Next: "Synthesis: Free Energy as the Master Variable"

Comments ()