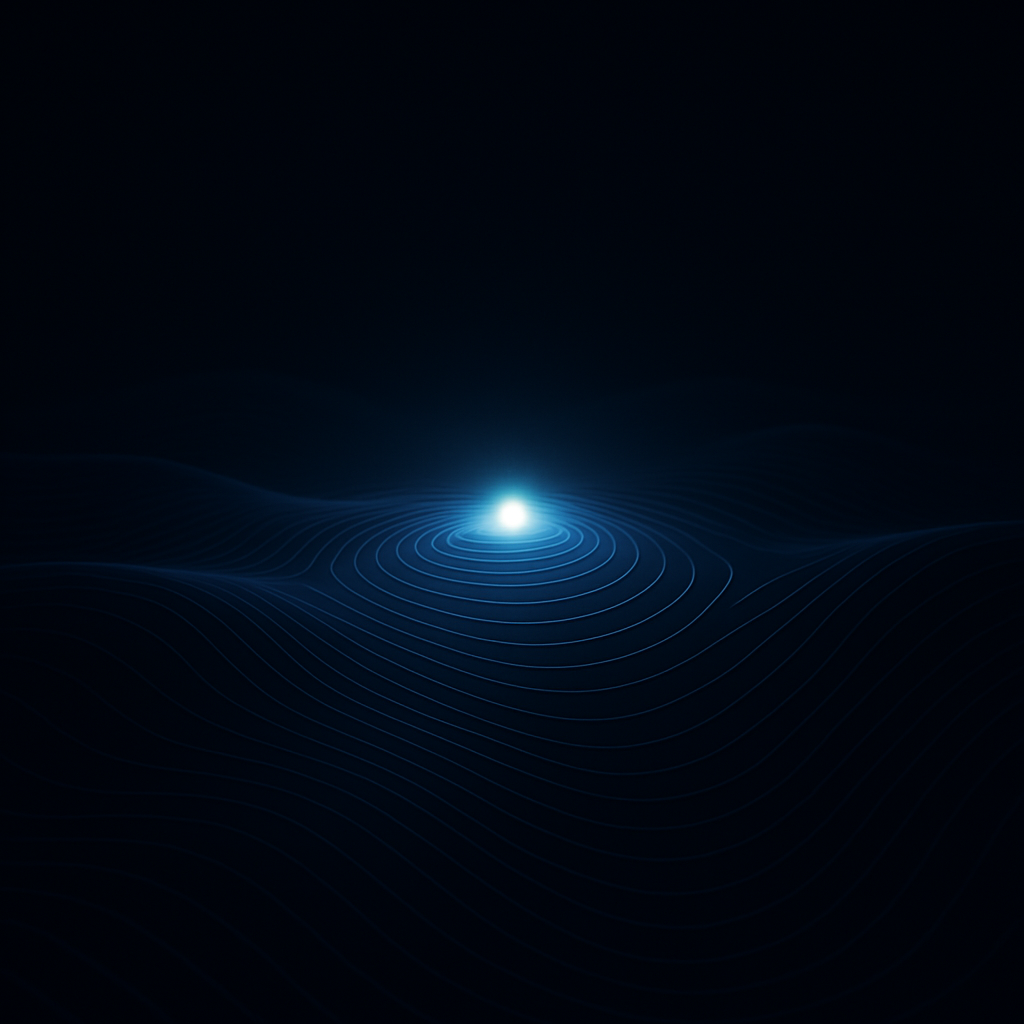

Your Mind Is a Point on a Surface You Can't See

Every belief is a point on an invisible manifold. Learn how information geometry reveals why some mental transitions flow naturally while others feel impossible.

Your Mind Is a Point on a Surface You Can't See

Formative Note

This essay represents early thinking by Ryan Collison that contributed to the development of A Theory of Meaning (AToM). The canonical statement of AToM is defined here.

You are somewhere.

Not in physical space—though you're there too—but in a space of possible beliefs, possible predictions, possible ways of modeling what the world is and what it will do next. Every configuration your mind could take corresponds to a location in this space. The configuration you have right now, reading this sentence, expecting certain words to follow and not others, is one point among inconceivably many.

This isn't poetry. It's mathematics. And the mathematics has a name: information geometry.

Information geometry is the study of probability distributions as geometric objects. It begins with a recognition that sounds abstract but lands concrete: the space of all possible probability distributions forms a surface with shape, distance, and curvature. That surface is real in the way that any mathematical structure is real—it has properties that don't depend on whether you believe in them, consequences that unfold whether you understand them or not.

Your mind, at any moment, holds a probability distribution over states of the world. What you expect to see when you turn your head. What you predict your partner will say next. What you believe will happen if you take this job, skip that meal, trust this stranger. All of it compresses into a point on a surface you've been navigating your whole life without knowing the surface existed.

This series is about making that surface visible.

The Manifold

Mathematicians call these surfaces manifolds. A manifold is a space that looks flat if you zoom in close enough but curves when you pull back. The surface of the Earth is a manifold—stand on it and it seems flat, but step back far enough and you see the sphere. The space of all possible belief states is a manifold too, though it lives in dimensions far beyond three.

A statistical manifold is a manifold whose points are probability distributions. Each point represents a complete model of uncertainty—a full accounting of what the system expects about everything it tracks. Move to a different point, and you have different expectations. Different predictions. A different model of reality.

This is more than abstraction. Consider what it means concretely.

You walk into a room. Before you process anything consciously, your brain has already generated a prediction about what the room contains—furniture arrangements, lighting conditions, the probability that another person is present, the likelihood of various sounds and smells. This prediction is a point on a manifold. It's not a single guess but a whole distribution: high probability that there's a floor, moderate probability of a table, low probability of a live tiger.

Now you look around. Sensory data arrives. Your prediction updates. The distribution shifts—this probability goes up, that one goes down, your model of the room becomes more precise or gets surprised by something unexpected.

That update is movement across the manifold. The distance you moved corresponds to how much your model changed. The path you took matters: some routes through belief-space are efficient, others costly, others impossible given where you started.

This is why two people can receive identical information and arrive at different conclusions. They started at different points on the manifold. The same evidence applied to different starting locations lands you in different places. What you can believe next depends on what you believe now—not because of stubbornness or bias, though those exist, but because of geometry. The shape of the surface constrains what movements are possible.

Why Shape Matters

The shape of the manifold isn't arbitrary. It's determined by the statistical structure of the distributions themselves—by how they relate to each other, how distinguishable they are, how much information separates one from another.

Some regions of the manifold are flat. In these regions, small changes in your beliefs produce proportionally small changes in your predictions. The world behaves roughly as expected. Updates are gentle. If you adjust your estimate of tomorrow's weather by a few percentage points, your behavior doesn't radically change. You're moving across smooth terrain.

Other regions are curved—sharply, steeply, dangerously. In these regions, the same small change in belief produces enormous changes in prediction. The model is sensitive here. Twitchy. A tiny shift in one parameter cascades through the whole distribution. Small perturbations become big effects. Navigation requires constant correction, and correction is expensive.

You've felt this difference even if you've never named it.

The flat regions feel stable. Calm. Predictable. You know roughly where you are and roughly where you're going. When surprises arrive, you absorb them. Your model updates without crisis. Life makes sense, not because nothing unexpected happens, but because the unexpected can be integrated.

The curved regions feel volatile. Anxious. Every input matters too much. A glance, a tone of voice, a silence that lasts a beat too long—each one sends the system into recalculation. The ground keeps shifting. You can't find stable footing because the surface itself is bent in ways that make stability expensive.

Trauma lives in the curved regions. Not as memory, not as narrative, but as geometry. The manifold has been deformed by overwhelming experience, and now small stimuli produce disproportionate responses. A door slam isn't just a door slam—it's a trajectory through high-curvature space where prediction error spikes and the system can't find smooth ground. The response isn't crazy. It's geometrically appropriate to the surface the system is navigating. The problem is that the surface got warped, and no one knows how to unwarp it.

This is why "just calm down" doesn't work. You're not asking someone to change their reaction. You're asking them to move to a different region of the manifold—which would be great, except they can't get there from here, not directly, not without crossing terrain that's even more destabilizing than where they already are. The geometry constrains what's possible.

Distance and Distinguishability

How do you measure distance on a manifold of probability distributions?

Not with a ruler. The distance between two beliefs isn't spatial. It's informational. Two distributions are "close" if they make similar predictions—if you can't easily tell them apart by their outputs. Two distributions are "far" if they make very different predictions—if the data that confirms one would disconfirm the other.

This is called the Fisher information metric, and we'll spend a whole article on it. For now, the key insight: distance on the statistical manifold corresponds to distinguishability. How far apart are two beliefs? As far apart as their predictions.

This matters because it means learning has geometry. When you update your beliefs, you travel a certain distance across the manifold. Big updates travel far. Small updates stay local. The total distance traveled over a lifetime of learning traces a path through belief-space—a trajectory that constitutes, in a meaningful sense, the shape of your cognitive life.

Some people's trajectories are smooth. They start with decent models, receive comprehensible evidence, update gracefully, and end up in reasonable places. Their path through the manifold is a gentle curve.

Other people's trajectories are jagged. They start with models that don't fit the world, receive evidence that shocks, update in fits and starts, get stuck in local minima, oscillate between distant attractors. Their path through the manifold is a series of leaps and crashes.

The difference isn't intelligence. It isn't effort. It's often just luck—what models you started with, what evidence the world provided, whether the surface you're navigating has smooth paths available or only hard ones.

The View from Inside

Here's the strange part: you can't see the manifold from inside it.

You experience beliefs as direct contact with reality. When you believe it will rain tomorrow, you don't feel yourself occupying a point on a probability surface. You feel like you're seeing the world, reading the weather, knowing something about tomorrow. The geometry is invisible.

But it's still operating. The constraints it imposes show up as felt limits on what you can think, what you can imagine, what updates feel possible. The shape of your local manifold region determines the texture of your mental life without announcing itself.

Consider trying to change someone's mind about something core to their identity. It's not just that they resist. It's that the movement you're asking for would require crossing enormous distances on the manifold—traversing regions of high curvature where every step is destabilizing. The "resistance" isn't psychological stubbornness. It's geometric cost. The path you're suggesting is expensive, maybe impossible, from where they stand.

Or consider the experience of sudden insight—the moment when something clicks, when a problem you've struggled with suddenly makes sense. What happened geometrically? You found a path. A route through the manifold opened up that wasn't visible before. The destination was always there; what changed was access.

Learning difficulties, cognitive rigidity, creative blocks, paradigm shifts, religious conversions, therapeutic breakthroughs—all of these have geometry. All of them involve movement across a manifold, or the failure to move, or the sudden discovery of a path.

The mathematics doesn't replace the psychology. But it reveals structure underneath it. Patterns that persist across contexts. Invariants that hold whether the manifold describes one person's beliefs or a whole culture's.

Neurons to Cultures

The same geometry applies at every scale. This is the claim that animates this entire series, and it begins here.

A single neuron maintains a distribution over inputs it expects to receive. Not consciously—neurons don't have beliefs the way you have beliefs—but functionally. The neuron's internal state encodes what firing patterns it predicts, what inputs would surprise it, what the world looks like from its tiny vantage point. That encoding is a point on a manifold. Learning shifts that point. Prediction error signals the distance between where the neuron "thinks" it is and where incoming data suggests it should be.

A brain is a vastly higher-dimensional version of the same thing. Each configuration of neural activity is a location in a space of possible global states. Perception, thought, emotion, action—these are trajectories. Paths through state space, constrained by the manifold's geometry.

Mental health is smooth navigation. The system moves fluidly through belief-space, updating as needed, exploring when appropriate, returning to stable attractors when the world calms down. The surface is navigable. The paths connect.

Mental illness is geometric breakdown. Getting stuck—locked in regions the system can't escape. Or careening—moving so fast through such curved regions that no stability is possible. Or fragmenting—the manifold itself developing holes, disconnected regions that can't communicate, parts of the mind that can't reach each other.

A relationship is two manifolds coupled. Two points moving in coordination, each one's location affecting where the other can go. When I update my beliefs about you, my location shifts. When you sense that shift—when your prediction of me updates—your location shifts too. We're dancing on linked surfaces, each step constraining and enabling the other's.

Attunement is synchronized movement. We're moving together, our trajectories aligned, the curvature we experience shared. Conflict is divergent trajectories—we're pulling toward different regions, and the coupling that connects us turns into tension. Repair is finding paths back to shared terrain, regions where both manifolds are smooth enough to navigate together.

An organization is a high-dimensional manifold of coupled predictive agents. When the organization is coherent, the agents can predict each other. Information flows because people know where others are on the manifold and can anticipate where they're going. Coordination emerges from geometric compatibility.

When organizational coherence breaks down, the manifold fragments. Silos form—subsystems whose locations on the manifold have drifted so far apart they can no longer predict each other. Communication fails because the distance has become too great. The geometry has fractured.

A culture is a manifold at civilizational scale. Millions of points, loosely coupled, constrained by shared narratives and institutions into rough alignment. When the culture is coherent, there's enough geometric agreement that collective action is possible. When the culture polarizes, the manifold splits—different populations occupying regions so distant that they can't even recognize each other's beliefs as beliefs.

Same surface. Different scale. The mathematics doesn't care whether the distributions describe single neurons or entire civilizations. The geometry is the geometry.

What This Series Will Do

This article is entry-level. The surface exists—that's the claim. Everything that follows will sharpen it.

The next article introduces the Fisher information metric properly: the mathematical object that defines distance on statistical manifolds. You'll see why some movements are longer than others, why some directions are easier to travel, and what it means precisely for a region to be "curved."

From there, we'll cover curvature in depth—what makes some minds, some relationships, some organizations hyper-reactive while others absorb perturbation smoothly. We'll examine the KL divergence—the formal measure of how far your model has drifted from reality, and what happens when that gap becomes unbridgeable.

Then topology: the study of global structure, of holes and loops and persistent features that organize the manifold at scales beyond local curvature. Why some people get stuck in loops. Why some organizations have bottlenecks they can't escape. Why some cultures develop attractors that trap them.

After that, category theory and constructor theory—the mathematics of structure preservation across scales, the formal language for explaining how coherence at one level becomes coherence at another. Why it's not just analogy when we say neurons and cultures follow the same rules. What makes the mapping precise.

And finally, synthesis. The coherence operator. The unified measure. The mathematics that ties it all together.

But all of it rests on what you now know: you are somewhere. The somewhere has shape. The shape determines what's possible.

The Invisible Ground

You've been navigating the manifold your whole life. Every belief you've formed, every opinion you've updated, every time you've learned something or failed to learn it or gotten stuck or broken through—all of it traced paths across a surface you couldn't see.

The surface didn't care that you couldn't see it. It constrained you anyway. It enabled certain movements and blocked others. It made some beliefs easy to reach from where you were and others impossible. It shaped what you could think without ever announcing itself.

Now you know it's there.

That knowledge doesn't change the geometry directly. Knowing about curvature doesn't flatten it. But it does change what you can do with the geometry. You can start to notice: Am I in a flat region or a curved one? Is this difficulty I'm having about willpower, or is it about terrain? When someone can't seem to change, are they stubborn, or are they standing somewhere that doesn't connect to where I want them to go?

The surface is real. The mathematics exists. The geometry governs.

This is where we start.

Comments ()