Every Cell Runs on an Ancient Bacterial Engine

In 1967, Lynn Margulis submitted a paper to fifteen journals. Fourteen rejected it. The fifteenth, the Journal of Theoretical Biology, finally published it—and it became one of the most important papers in the history of biology.

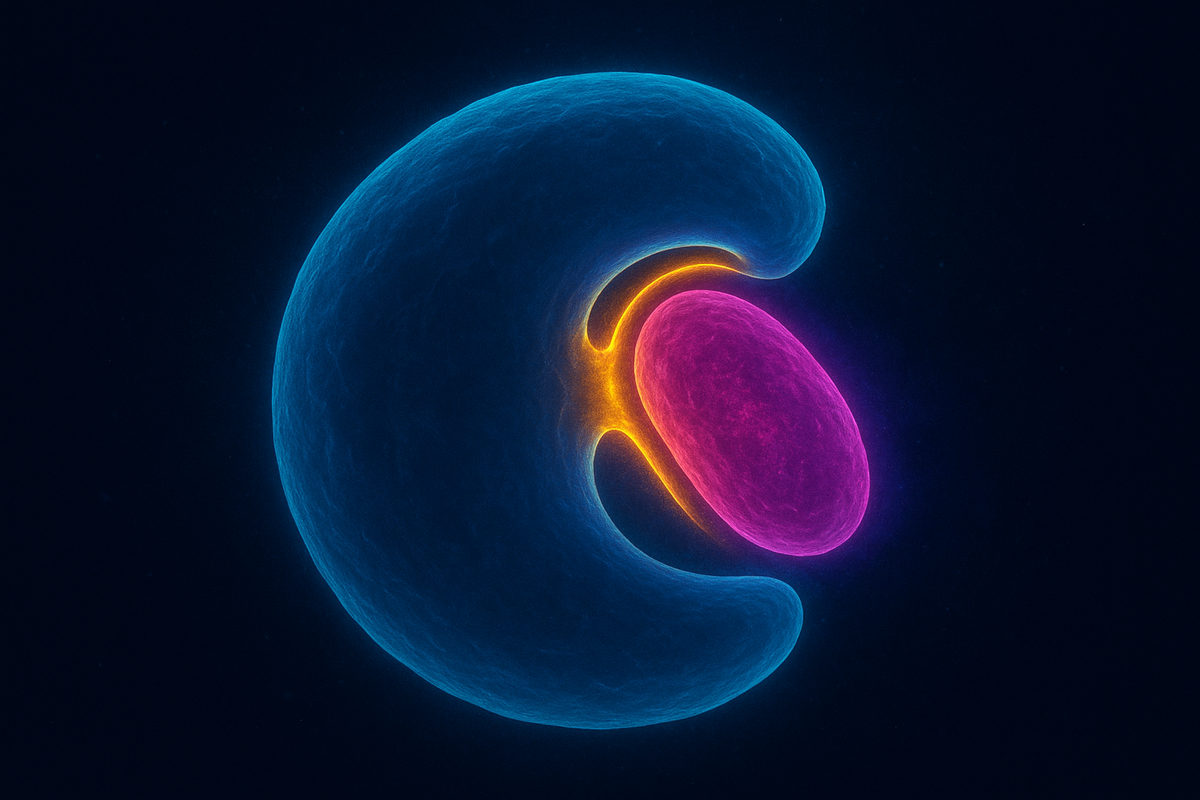

Her claim was outrageous: mitochondria, the power-generating organelles in every animal, plant, and fungal cell, were not originally part of those cells. They were once free-living bacteria. Billions of years ago, an ancestral cell engulfed a bacterium—or the bacterium invaded the cell—and instead of being digested, the bacterium stayed. It became permanent. It became the mitochondrion.

The scientific establishment thought this was ridiculous. Organelles from bacteria? Cells swallowing other cells and keeping them as internal organs? It sounded like science fiction. Margulis was mocked, dismissed, and ignored.

She was also completely right.

You are not a single organism. You are a collaboration that started two billion years ago.

The Evidence

Margulis didn't just assert that mitochondria were bacterial. She assembled evidence. Decades later, we have even more.

Mitochondria have their own DNA. This was strange from the beginning—why would an organelle need its own genome? The nuclear genome should be sufficient. But mitochondria maintain a small, circular chromosome, just like bacteria do. Human mitochondrial DNA contains 37 genes, encoding components essential for energy production.

Mitochondrial DNA looks bacterial. It's circular, not linear like nuclear chromosomes. It lacks the histone proteins that wrap nuclear DNA. It uses a slightly different genetic code. It replicates independently of the cell cycle. Everything about it screams "bacterium."

Mitochondria have double membranes. The outer membrane is thought to derive from the host cell's engulfment process. The inner membrane—with its characteristic folds called cristae—is the original bacterial membrane, retained after two billion years.

Mitochondrial ribosomes are bacterial-type. Ribosomes are the protein-making machines in cells. Cytoplasmic ribosomes (80S) are different from bacterial ribosomes (70S). Mitochondrial ribosomes? They're 70S. Bacterial. This is why certain antibiotics that target bacterial ribosomes can have mitochondrial side effects.

Phylogenetic analysis confirms it. When you compare mitochondrial gene sequences to those of living bacteria, you find a match: alphaproteobacteria, specifically relatives of modern Rickettsia—intracellular parasites. The ancestral mitochondrion was related to bacteria that still invade cells today.

The case is closed. Mitochondria are domesticated bacteria.

The Great Merger

Let's reconstruct what happened.

Somewhere between 1.5 and 2 billion years ago, Earth was populated by prokaryotes—simple cells without nuclei. Bacteria and archaea. No complex life. No animals, no plants, no fungi.

Then something unprecedented occurred.

An archaeal cell—probably something like modern Asgard archaea, based on recent genomic evidence—encountered a bacterium. Maybe the archaeon tried to eat the bacterium. Maybe the bacterium invaded the archaeon. Maybe it was something in between—a parasitic relationship that gradually became mutualistic.

Whatever the initial contact, the bacterium didn't get digested. It survived inside the host cell. And it could do something the host couldn't: efficiently extract energy from oxygen.

This was the key. The bacterium had sophisticated machinery for oxidative phosphorylation—using oxygen to generate ATP, the universal energy currency. The host cell probably had less efficient metabolic pathways. The bacterium offered power.

In exchange, the bacterium got protection and nutrients. A stable environment. Safety from the outside world.

Over millions of years, the relationship deepened. The bacterium transferred most of its genes to the host nucleus—keeping only a small set essential for respiration. The host cell evolved machinery to import proteins into mitochondria, coordinate their division, and integrate their function.

Two organisms became one. The eukaryotic cell was born.

Every complex cell on Earth descends from this merger. You exist because a bacterium and an archaeon made a deal.

Lynn Margulis: The Outsider Who Was Right

Margulis didn't discover the idea of symbiosis—earlier scientists had proposed something similar. But she championed it when it was deeply unfashionable, assembled the evidence, and fought for it against withering criticism.

The establishment dismissed her for years. She was denied grants. She was called a crank. One famous biologist said her endosymbiotic theory was "too fantastic to be taken seriously."

She persisted. She refined the theory. She accumulated evidence. She argued that not just mitochondria but also chloroplasts (the photosynthetic organelles in plants) originated from engulfed bacteria—cyanobacteria, in that case.

By the 1980s, DNA sequencing proved her right. Mitochondrial and chloroplast genes were clearly bacterial in origin. The "fantastic" theory became textbook biology.

Margulis's broader vision went further. She argued that symbiosis—not just competition—was a major driver of evolution. Life doesn't just compete; it merges. Organisms don't just fight; they cooperate, sometimes to the point of fusion.

The evolution of complex life wasn't survival of the fittest. It was survival of the most cooperative.

She died in 2011, having revolutionized our understanding of how cells evolved. The fifteen journals that rejected her paper would have been better served by publishing it.

The Alphaproteobacterial Ancestor

What was the original mitochondrion like?

Based on phylogenetic reconstruction, the ancestral mitochondrion was an alphaproteobacterium—a member of the same bacterial group that today includes Rickettsia (which causes typhus), Rhizobium (which fixes nitrogen in plant root nodules), and various other species.

Many alphaproteobacteria are intracellular—they naturally live inside other cells. Some are parasites; others are mutualists. The lineage seems predisposed to intimate cellular relationships.

The ancestral mitochondrion probably had a complete genome, capable of independent life. Over evolutionary time, most of those genes migrated to the nucleus. Today, human mitochondrial DNA contains just 37 genes, encoding: - 13 proteins (all involved in oxidative phosphorylation) - 22 transfer RNAs - 2 ribosomal RNAs

That's it. Everything else mitochondria need—and they need a lot—gets imported from the cytoplasm, encoded by nuclear genes, made by cytoplasmic ribosomes, and shipped into the mitochondria via specialized import machinery.

The bacterium has been stripped down to its essential function: making ATP.

Why Keep Any Genes?

Here's a puzzle: if most mitochondrial genes moved to the nucleus, why didn't all of them?

The nuclear location seems safer. Nuclear DNA has better repair mechanisms. It's more stable. It benefits from sexual recombination, which mitochondrial DNA (maternally inherited) lacks.

So why do mitochondria stubbornly retain 37 genes?

Several hypotheses:

The hydrophobicity problem. The 13 proteins encoded by mitochondrial DNA are all highly hydrophobic—they need to embed in membranes. Hydrophobic proteins are notoriously difficult to import across membranes; they tend to aggregate. Making them inside the mitochondrion, right where they're needed, may be the only practical option.

Local control. Mitochondria need to respond rapidly to energy demands. Having some genes locally allows faster response—no need to signal the nucleus, wait for transcription, wait for translation, wait for import.

Co-location for redox regulation (CoRR). Nick Lane and others have proposed that the genes encoding core respiratory chain components must stay in the mitochondrion to allow fine-tuned coordination between gene expression and electron flow. If the genes were nuclear, the mitochondrion couldn't regulate them in response to local conditions.

Whatever the reason, the 37 remaining genes create problems. Mitochondrial DNA mutates about 10 times faster than nuclear DNA. It has limited repair mechanisms. Mutations accumulate over a lifetime. This matters for aging, as we'll see later in this series.

The Energy Revolution

The merger that created mitochondria wasn't just a biological curiosity. It was an energy revolution.

Before the merger, prokaryotic cells had limited surface area for generating ATP. Energy production happened at the cell membrane. If you wanted more energy, you needed more membrane. But more membrane meant more cell surface area, which required more material, more genes, more everything. There was a ceiling.

Mitochondria broke through the ceiling.

By internalizing the energy-producing membranes, eukaryotic cells could pack far more ATP-generating capacity into the same volume. The inner mitochondrial membrane, with its elaborate folds (cristae), provides enormous surface area for respiration. A single cell can contain hundreds or thousands of mitochondria.

The result: eukaryotic cells have vastly more energy available per gene than prokaryotic cells. Estimates suggest 10,000 to 100,000 times more.

This surplus powered everything that came after. The complex gene regulation that allows differentiated cell types. The elaborate cytoskeleton that allows cell movement and internal organization. The ability to engulf other cells (phagocytosis), which is itself energy-intensive. The evolution of multicellularity.

Bacteria have been around for nearly 4 billion years. They've never independently evolved true multicellularity, complex cell types, or tissue differentiation. They couldn't. They didn't have the power.

Eukaryotes had mitochondria, so eukaryotes had power, so eukaryotes could experiment. All complex life on Earth—every animal, every plant, every fungus—descends from that original merger.

Nick Lane, in his book The Vital Question, argues that this is not a coincidence. Energy constraints fundamentally limit what life can do. The mitochondrial merger was the breakthrough that allowed life to escape the bacterial ceiling.

Not Just Powerplants

For a long time, mitochondria were treated as simple batteries. Fuel goes in, ATP comes out, end of story.

We now know they're much more than that.

Cell death gatekeepers. Mitochondria control apoptosis—programmed cell death. When a cell should die (because it's damaged, infected, or no longer needed), mitochondria release cytochrome c into the cytoplasm, triggering the cell's self-destruction cascade. They hold the kill switch.

Calcium buffers. Mitochondria take up and release calcium ions, modulating cytoplasmic calcium levels. This affects everything from muscle contraction to neurotransmitter release.

Biosynthetic hubs. Mitochondria are where certain essential molecules get made: heme (for hemoglobin), steroid hormones, iron-sulfur clusters (needed by many enzymes).

Stress sensors. Mitochondria detect nutrient status, oxygen levels, and cellular damage. They communicate this information to the nucleus through "retrograde signaling"—the organelle talking back to its host.

Immune activators. Damaged mitochondria release molecules that trigger inflammation. Mitochondrial DNA, if it leaks into the cytoplasm, looks like bacterial DNA to the immune system (because it is, evolutionarily), activating inflammatory pathways.

The more we study mitochondria, the more central they become to cellular physiology. They're not just the power plant. They're a regulatory hub, integrating information about cellular status and coordinating responses.

The Implications

The endosymbiotic origin of mitochondria has profound implications.

You are not genetically unified. Your nuclear genome and your mitochondrial genome have different evolutionary histories. They have to work together, but their interests don't always align. Mito-nuclear conflict is a real phenomenon, with implications for fertility, aging, and disease.

Your mother is special. Mitochondria are inherited maternally (with rare exceptions). Your mitochondrial DNA came from your mother, and hers from her mother, in an unbroken chain back to the original merger. Paternal mitochondria are actively destroyed after fertilization. You carry your mother's bacterial symbionts.

Cooperation can outcompete competition. The merger that created eukaryotes wasn't a competitive victory. It was a collaborative one. Two organisms combined their capabilities and became more than either could be alone. Evolution isn't only about struggle; it's also about partnership.

Identity is complicated. Where do "you" end and your mitochondria begin? They have their own genome, their own replication, their own evolutionary interests. They're inside you, but are they you? The boundaries of the self blur when you look closely.

Further Reading

- Margulis, L. (1967). "On the origin of mitosing cells." Journal of Theoretical Biology. - Lane, N. (2015). The Vital Question: Energy, Evolution, and the Origins of Complex Life. W.W. Norton. - Gray, M. W. (2012). "Mitochondrial Evolution." Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. - Roger, A. J., Muñoz-Gómez, S. A., & Kamikawa, R. (2017). "The Origin and Diversification of Mitochondria." Current Biology.

This is Part 1 of the Mitochondria Mythos series, exploring the bacterial engines at the heart of complex life. Next: "ATP: The Energy Currency of Life."

Comments ()