Mitochondrial DNA: Your Other Genome

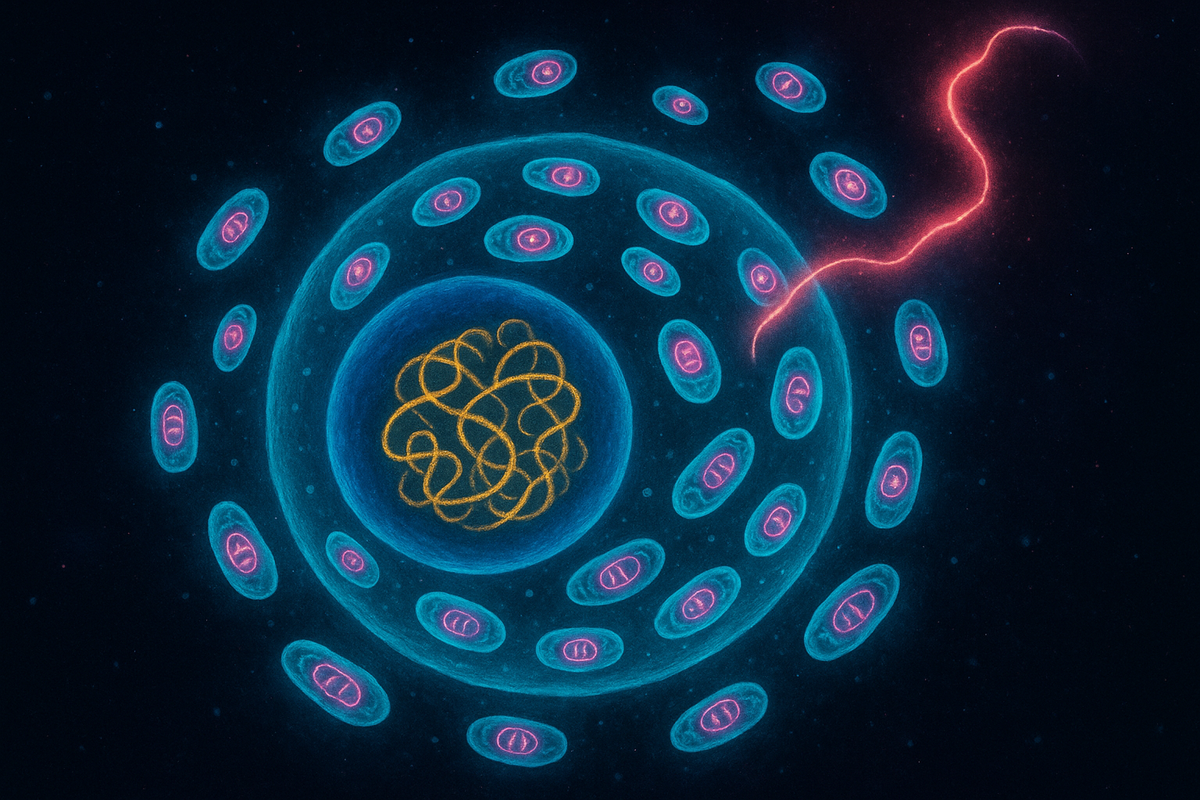

You have two genomes.

One sits in the nucleus of every cell—about 3 billion base pairs spread across 23 chromosome pairs, inherited from both parents, encoding roughly 20,000 genes. This is the genome everyone talks about. The one 23andMe analyzes. The one that carries most of your hereditary information.

The other one is smaller, stranger, and entirely maternal.

Mitochondrial DNA is a tiny circular chromosome—just 16,569 base pairs in humans—that lives inside your mitochondria. It encodes only 37 genes. It came from your mother, and her mother, and her mother's mother, in an unbroken chain reaching back before our species existed.

Your nuclear genome is a mix of your parents. Your mitochondrial genome is your mother's alone.

You carry two genomes with different histories, different inheritance patterns, and different vulnerabilities. They have to work together. Sometimes they don't.

The Remnant Chromosome

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is what remains of the original bacterial genome.

When the ancestral mitochondrion took up residence inside a host cell two billion years ago, it had a complete bacterial genome—thousands of genes, everything needed for independent life. Over evolutionary time, most of those genes migrated to the nucleus. The mitochondrion was stripped down.

What stayed behind are the genes for: - 13 proteins: All subunits of the electron transport chain and ATP synthase - 22 tRNAs: Transfer RNAs for mitochondrial protein synthesis - 2 rRNAs: Ribosomal RNAs for mitochondrial ribosomes

That's it. Thirty-seven genes, encoding components essential for oxidative phosphorylation. Everything else mitochondria need—the enzymes of the citric acid cycle, the import machinery, the DNA replication proteins—is encoded in the nucleus and imported.

The mtDNA is circular, like a bacterial chromosome. It's not wrapped around histones like nuclear DNA. It uses a slightly different genetic code (in humans, AGA and AGG code for STOP instead of arginine). It's prokaryotic in structure but enslaved to eukaryotic function.

Maternal Inheritance

Here's one of the most striking features of mtDNA: you inherited all of it from your mother.

Sperm cells have mitochondria—they need them to power the flagellum that propels them toward the egg. But when a sperm fertilizes an egg, those paternal mitochondria are actively destroyed. The egg cell contains molecular machinery that recognizes and eliminates sperm mitochondria through autophagy (cellular self-digestion).

Why? Several hypotheses:

Avoiding conflict. If you inherited mitochondria from both parents, you'd have two different mtDNA lineages competing for replication inside your cells. Competition between genomes can lead to selfish mutations—variants that replicate faster but work less well. Eliminating one parent's mitochondria prevents this conflict.

Quality control. Sperm mitochondria have been working hard—their electron transport chains have been running flat out to power the swim. They've likely accumulated oxidative damage. The egg's mitochondria are relatively quiescent, fresher, less damaged. Better to start with the healthier stock.

Simplifying inheritance. Uniparental inheritance creates a clean lineage. Each person's mtDNA traces back through a single maternal line, unconfused by recombination. This makes mtDNA extremely useful for tracking ancestry—and extremely vulnerable to problems when mutations occur.

Your mitochondrial genome came from one person: your mother. And hers from hers. Trace it back far enough, and you reach Mitochondrial Eve.

Mitochondrial Eve

She lived in Africa, roughly 150,000-200,000 years ago.

Mitochondrial Eve is the most recent common ancestor of all living humans through the maternal line. Every human mtDNA today descends from hers. This doesn't mean she was the only woman alive—there were thousands of others—but their maternal lineages eventually died out (when a woman has no daughters, her mtDNA lineage ends).

The concept confused some people when it was first publicized. Eve wasn't the first human. She wasn't the only woman of her time. She's simply the most recent woman from whom all existing mtDNA derives—a statistical consequence of genetic drift and lineage extinction over thousands of generations.

mtDNA's maternal inheritance and lack of recombination make it ideal for tracing ancestry. Mutations accumulate at a roughly constant rate, serving as a molecular clock. By comparing mtDNA sequences across populations, geneticists have reconstructed human migration patterns out of Africa and across the globe.

The African origin of humanity, the route through the Middle East into Europe and Asia, the later colonization of Australia and the Americas—mtDNA has helped trace all of it.

The Mutation Problem

mtDNA mutates faster than nuclear DNA. About 10-17 times faster, depending on the region.

Several factors contribute:

Proximity to the electron transport chain. mtDNA sits right next to the machinery producing reactive oxygen species. It's bathed in free radicals. Nuclear DNA is relatively protected inside the nucleus, away from the mitochondrial furnace.

Limited repair. Mitochondria have DNA repair mechanisms, but they're less sophisticated than the nuclear repair systems. Some types of damage that would be fixed in the nucleus persist in mtDNA.

No protective histones. Nuclear DNA is wrapped around histone proteins, which provide some protection. mtDNA is naked—no histones, no protection.

High copy number with selection bias. Each cell contains hundreds to thousands of mitochondria, each with multiple copies of mtDNA. Variants that replicate faster can spread through the population even if they're functionally worse—a form of selfish genetic element.

The result: mutations accumulate. Over your lifetime, your mtDNA becomes increasingly heteroplasmic—a mix of normal and mutant copies.

Heteroplasmy: The Mixed Bag

Unlike nuclear genes, where you have exactly two copies (one maternal, one paternal), mtDNA comes in hundreds or thousands of copies per cell. And they're not all identical.

Heteroplasmy is the coexistence of different mtDNA variants within the same cell or individual. You might have 80% normal mtDNA and 20% mutant mtDNA. Or the proportions might vary between tissues—more mutant copies in muscle, fewer in liver.

This creates a threshold effect. Many mtDNA mutations don't cause symptoms until the proportion of mutant copies exceeds a critical level—often 60-80%. Below that threshold, the normal copies can compensate. Above it, cellular function collapses.

The threshold varies by tissue. Brain and muscle, which have high energy demands, are especially vulnerable. Heart, similarly. Cells that can't make enough ATP start to fail.

The same mutation can cause no symptoms, mild symptoms, or lethal disease, depending on the proportion of mutant copies and which tissues are affected.

Mitochondrial Diseases

When mtDNA goes wrong, the consequences can be devastating.

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) causes sudden blindness in young adults, typically males. Mutations in mtDNA-encoded Complex I subunits impair ATP production in the optic nerve. Vision loss can be rapid and permanent.

MELAS (Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Stroke-like episodes) causes strokes in young people, seizures, muscle weakness, and cognitive decline. It's caused by mutations in a mitochondrial tRNA gene.

MERRF (Myoclonic Epilepsy with Ragged Red Fibers) causes epilepsy, muscle weakness, and abnormal mitochondria visible on muscle biopsy as "ragged red fibers."

Kearns-Sayre syndrome causes progressive external ophthalmoplegia (paralysis of eye muscles), heart conduction defects, and retinal degeneration. It's often caused by large deletions in mtDNA.

These diseases are rare but brutal. They disproportionately affect high-energy tissues—brain, muscle, heart, retina. There are few effective treatments. The underlying problem is energetic: cells can't make enough ATP to function.

And because mtDNA is maternally inherited, affected women face an agonizing dilemma. If a mother carries a mtDNA mutation, she will pass it to all her children. The proportion inherited is random—some children may get mostly normal copies, others mostly mutant. It's a genetic lottery with devastating stakes.

The Bottleneck

Here's something strange: heteroplasmy levels can shift dramatically between generations.

A mother with 30% mutant mtDNA might have one child with 10% and another with 80%. How does this variance arise?

The answer is the mitochondrial bottleneck.

During early development, the number of mtDNA copies per cell drops dramatically—from hundreds of thousands in the egg to perhaps 200-2000 in the primordial germ cells that will become the next generation's eggs. This is the bottleneck.

If a mother is heteroplasmic, each of those few mtDNA copies in the bottleneck represents a sample from her mix. Random sampling causes variance. One primordial germ cell might, by chance, receive mostly normal copies; another might receive mostly mutant. As those cells then amplify their mtDNA during egg development, the proportions are locked in.

The bottleneck amplifies genetic drift. It's why mtDNA disease risk is so unpredictable between siblings.

Mito-Nuclear Incompatibility

Here's a subtler problem: the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes have to work together. They co-evolve. And sometimes they clash.

The electron transport chain is built from both mtDNA-encoded and nuclear-encoded subunits. Complex I, for example, has 7 subunits encoded by mtDNA and 38 encoded by the nucleus. These subunits must physically interact, fitting together precisely.

When they come from different genetic backgrounds—as in interspecies hybrids, or when mismatched by mitochondrial replacement therapy—they may not fit well. The machine malfunctions.

Within species, most people have well-matched mito-nuclear combinations—their mtDNA and nuclear genome have co-evolved. But mismatches can occur, especially in admixed populations or when mtDNA mutations affect interaction surfaces.

Mito-nuclear incompatibility has been linked to reduced fertility, developmental problems, and potentially some aspects of aging. The two genomes are in a forced partnership, and like any partnership, conflict is possible.

Aging and mtDNA

The mitochondrial theory of aging proposes that accumulating mtDNA mutations contribute to the decline we experience as we get older.

The logic is straightforward: mtDNA mutates faster than nuclear DNA. Damage accumulates over a lifetime. As mutant mtDNA copies spread (through a process called clonal expansion), more cells cross the threshold into dysfunction. Energy production falters. Tissues degrade.

The evidence is mixed but intriguing:

mtDNA mutations accumulate with age. Studies consistently find more mtDNA damage in older individuals and in post-mitotic tissues (like brain and muscle) that can't dilute mutations through cell division.

mtDNA mutator mice age prematurely. Mice engineered to have error-prone mtDNA polymerase accumulate mutations rapidly and show early-onset aging phenotypes: graying hair, weight loss, osteoporosis, heart problems.

But correlation isn't causation. mtDNA mutations might be a consequence of aging rather than a cause, or one of many contributing factors rather than the dominant driver.

The relationship between mtDNA and aging remains an active research area. What's clear is that mitochondrial function declines with age, and mtDNA integrity is part of that story.

Forensics and Ancestry

mtDNA's unique properties make it invaluable for identification.

High copy number. While nuclear DNA is present in only two copies per cell, mtDNA exists in thousands of copies. Even when nuclear DNA is too degraded to analyze—in ancient bones, decomposed remains, or trace evidence—mtDNA may still be recoverable.

Maternal lineage. mtDNA connects individuals through maternal lines. This has been used to identify remains of the Romanov royal family, victims of war crimes, and unnamed soldiers from past conflicts.

Population genetics. mtDNA haplogroups—clusters of related sequences—track maternal ancestry and migration patterns. Genetic genealogy services use mtDNA to connect people with distant maternal relatives.

The limitations are real: mtDNA can't distinguish between siblings who share a mother, and it provides only one line of ancestry among many. But for cases where nuclear DNA fails, mtDNA can be the only option.

The Other Genome

Your mitochondrial DNA is a window into deep time.

It's the genome of a bacterium that your ancestors engulfed two billion years ago. It's been passed from mother to child for millions of generations without recombination, accumulating mutations like a molecular diary. It traces a line from you to your mother, to her mother, back through prehistoric migrations, through the emergence of Homo sapiens, through primate evolution, through the mammalian radiation, back to the original eukaryotic merger.

The other genome. The maternal genome. The bacterial remnant that powers your cells.

You are not one lineage but two, intertwined.

Further Reading

- Wallace, D. C. (2005). "A Mitochondrial Paradigm of Metabolic and Degenerative Diseases, Aging, and Cancer." Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. - Stewart, J. B., & Chinnery, P. F. (2015). "The dynamics of mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy." Nature Reviews Genetics. - Cann, R. L., Stoneking, M., & Wilson, A. C. (1987). "Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution." Nature. - Craven, L., et al. (2010). "Pronuclear transfer in human embryos to prevent transmission of mitochondrial DNA disease." Nature.

This is Part 3 of the Mitochondria Mythos series. Next: "NAD+ and Aging: David Sinclair's Bet."

Comments ()