Three-Parent Babies: Mitochondrial Replacement Therapy

In 2016, a baby was born with DNA from three people.

His mother carried a mutation in her mitochondrial DNA that causes Leigh syndrome—a devastating neurological disorder that had already killed two of her children. There was no way to prevent passing the mutation to another child through normal reproduction. The defective mitochondria would come along with the egg.

Unless you removed them.

A team led by John Zhang used a technique called spindle transfer. They took the nucleus from the mother's egg and transferred it to a donor egg whose nucleus had been removed—but whose healthy mitochondria remained. The resulting egg had the mother's nuclear DNA (all 20,000+ genes) and the donor's mitochondrial DNA (37 genes). After fertilization with the father's sperm, the embryo had genetic material from three people.

The baby was born healthy. He carries less than 1% mutant mitochondria.

This is mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT)—a technology that prevents mitochondrial disease by replacing defective mitochondria with healthy ones. It creates children with three genetic parents. And it raises questions about identity, inheritance, and the limits of medical intervention that we're still working through.

We can now prevent mitochondrial disease. The cost is rewriting the rules of genetic parenthood.

The Problem MRT Solves

Mitochondrial diseases are cruel.

They're caused by mutations in mitochondrial DNA or, sometimes, nuclear genes that affect mitochondrial function. The symptoms vary depending on which tissues are affected and how severe the mutation is, but they often include:

- Muscle weakness and exercise intolerance - Neurological problems: seizures, developmental delay, stroke-like episodes - Heart failure - Blindness, deafness - Diabetes - Organ failure

There's no cure. Treatment is supportive—managing symptoms, not fixing the underlying defect. For severe mutations, the prognosis is often death in childhood.

About 1 in 5,000 people carry pathogenic mitochondrial mutations. Most carriers don't have severe disease—the proportion of mutant mitochondria is below the threshold for symptoms. But affected families face an awful lottery. A mother with 30% mutant mitochondria might have one child with 10% (healthy) and another with 80% (severely ill), due to the random bottleneck during egg development.

There's no way to predict or control which children will be affected. Prenatal diagnosis can detect high mutation loads, but the only option then is termination. If you want healthy children, and you carry a severe mutation, your options are limited: use donor eggs, adopt, or take the gamble.

MRT offers a fourth option: have a genetically related child with healthy mitochondria from a donor.

How It Works

Two main techniques exist:

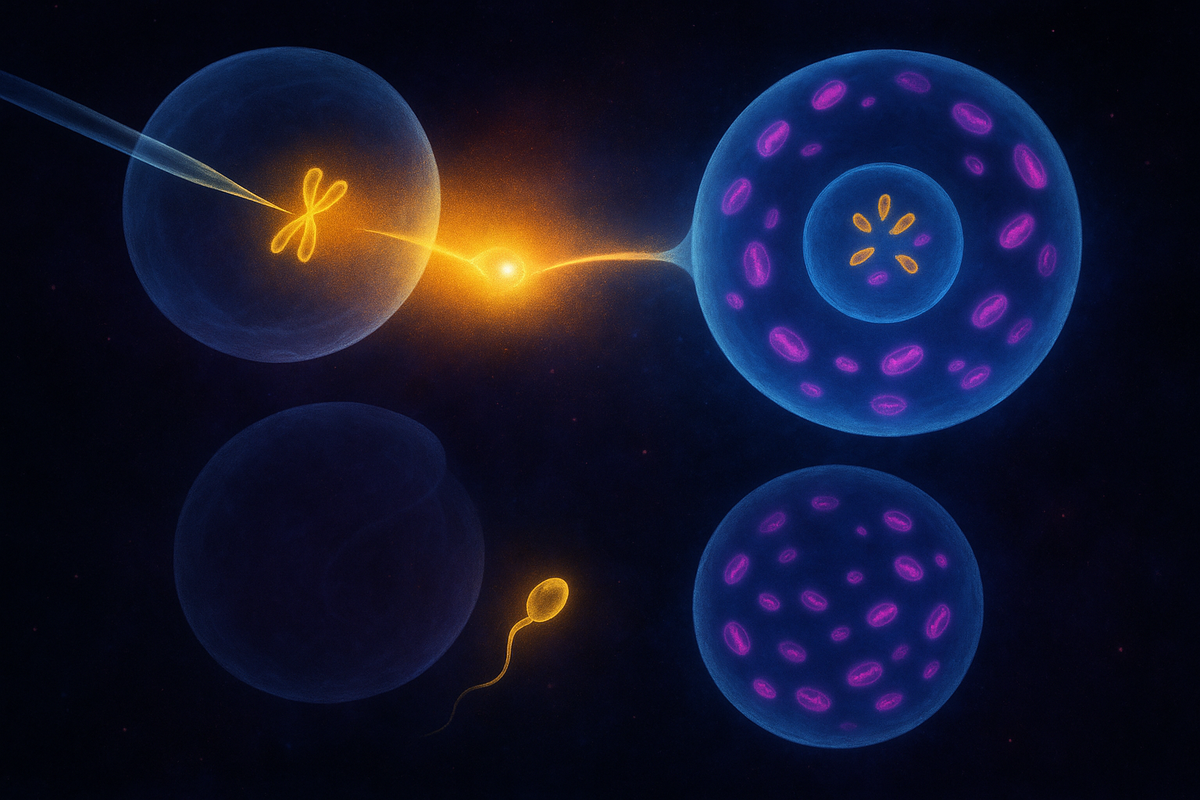

Maternal spindle transfer (MST): The mother's egg is collected. The spindle—the structure that holds the chromosomes during cell division—is extracted and transferred to a donor egg whose own spindle has been removed. The resulting reconstructed egg contains the mother's chromosomes and the donor's cytoplasm (including mitochondria). The egg is then fertilized with the father's sperm.

Pronuclear transfer (PNT): Both the mother's egg and a donor egg are fertilized first. Then, before the pronuclei (the early nuclei from egg and sperm) fuse, the pronuclei from the mother's fertilized egg are transferred to the donor egg whose pronuclei have been removed. The result is the same: nuclear DNA from the intended parents, mitochondrial DNA from the donor.

Both techniques aim to achieve the same outcome. The child inherits nuclear genes from their mother and father and mitochondrial genes from a donor. Three genetic contributions, combined into one person.

The UK Leads

The United Kingdom became the first country to legalize MRT for clinical use.

After years of scientific review and public consultation, Parliament amended the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act in 2015 to permit mitochondrial donation. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) now licenses clinics to offer the procedure.

The first UK baby born through MRT was announced in 2023. The procedure is tightly regulated—only approved for families with serious mitochondrial disease, only at licensed clinics, with ongoing monitoring of children born through the technique.

The US has taken a different path. The FDA has not approved MRT for clinical use. The technique is technically illegal in the US due to a congressional rider prohibiting FDA review of applications involving heritable genetic modifications.

The baby born in 2016 (the Zhang case) was born in Mexico, where regulations were less restrictive. This raised concerns about "reproductive tourism"—families seeking procedures abroad that aren't permitted at home.

The technology exists. The ethics and regulations are still catching up.

Three Parents?

Let's be clear about what "three-parent baby" means.

The child has nuclear DNA from two parents—mother and father, or two individuals contributing egg and sperm. This is the DNA that determines most traits: appearance, intelligence, personality, disease risk for most conditions.

The child also has mitochondrial DNA from a donor. This is 37 genes, encoding components of the energy production machinery.

Is the mitochondrial donor a "parent"?

In one sense, yes. The donor made a genetic contribution that will be inherited by the child and all their descendants through the maternal line. The mitochondrial lineage has been changed.

In another sense, no. The donor contributed no nuclear DNA. The child won't look like the donor, think like the donor, or have personality traits from the donor. The contribution is more like a transplant—an organ donation at the cellular level.

The social and legal implications are still being worked out. In the UK, mitochondrial donors are anonymous; children don't have the right to identify them. The donor is not considered a legal parent. But the genetic contribution is real and heritable.

The child has three genetic contributors but two legal parents. Biology and law don't always align.

Safety Concerns

MRT is new. Long-term safety data doesn't exist yet.

Concerns include:

Carryover. When you transfer a spindle or pronuclei, some of the mother's cytoplasm—including some mitochondria—comes along. The goal is to minimize this, but it's not zero. If too much mutant mtDNA carries over, the child might still develop disease. Early data suggests carryover can be reduced to <2%, but the threshold for safety depends on the specific mutation.

Reversion. In some cases, the small amount of mutant mtDNA that carries over might preferentially replicate and increase in proportion over time. This "reversion" could undermine the therapeutic goal. It's been observed in some studies, though not consistently.

Mito-nuclear incompatibility. The mitochondrial and nuclear genomes have to work together. When you mix nuclear DNA from one lineage with mitochondrial DNA from another, there's a theoretical risk of mismatch. In practice, this seems to be minimal for within-species transfers, especially within the same population. But it's a consideration.

Epigenetic effects. The egg's cytoplasm contains more than mitochondria—it has regulatory factors that affect early development. Swapping cytoplasm could, in theory, affect gene expression in ways we don't understand.

Unknown unknowns. The children born through MRT are young. We won't know the full safety profile for decades. This is inherent in any new reproductive technology.

The risk-benefit calculus depends on the alternative. For families with severe mitochondrial disease, the alternative is affected children who suffer and die. In that context, unknown long-term risks may be acceptable.

The Ethical Landscape

MRT raises ethical questions that go beyond safety.

Germline modification. MRT changes the germline—the genetic lineage that passes to future generations. This is different from treating a disease in one person. The mitochondrial DNA change will be inherited by all maternal descendants of the child, theoretically forever.

Some see this as a bright line. Germline modification has been forbidden by various international guidelines and national laws. MRT crosses that line.

Others argue that the line is arbitrary. We already make permanent changes to the human lineage through selective mating, prenatal genetic diagnosis, and even sperm/egg donation. MRT is just another tool.

Designer babies? MRT is not "enhancement"—it's disease prevention. The donor mitochondria aren't selected for superior function; they're simply not defective. But critics worry about the slippery slope. If we modify the germline for one purpose, what stops us from modifying it for others?

The response: slippery slope arguments apply to everything. Each technology should be judged on its own merits.

Identity. What does it mean for a child's identity to have three genetic contributors? The nuclear DNA defines most of what we think of as a person—but mitochondria aren't nothing. They're the descendants of an ancient symbiont. Does changing the mitochondrial lineage affect identity in a meaningful way?

Philosophically, the question has no clear answer. Practically, children born through MRT seem to be developing normally, with no apparent identity issues specific to their origins.

Consent. The child cannot consent to the procedure. Neither can their future descendants, who will inherit the modified mitochondria. This is true of all reproductive decisions—children never consent to being born, and genetic choices made by parents are always imposed on future generations.

The Alternative: Selection

MRT isn't the only approach to preventing mitochondrial disease.

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) can measure mtDNA mutation levels in embryos created through IVF. Embryos with low mutation levels can be selected for transfer. This works when the mother's heteroplasmy is not too severe—when there's a good chance some eggs will have low mutation loads.

For women with very high mutation levels (homoplasmic or near-homoplasmic for the mutation), PGD doesn't help—all embryos will have the mutation. MRT is the only option for genetically related children.

Egg donation is always an option but means the child has no genetic connection to the mother.

The choice between MRT, PGD, and egg donation depends on the specific situation. MRT fills a niche: severe mitochondrial mutation plus desire for genetic motherhood.

The Future

MRT is now a clinical reality, at least in the UK. Other countries are watching and debating.

The technique may evolve. Researchers are exploring ways to further reduce carryover, improve efficiency, and expand access. Gene editing of mitochondrial DNA is theoretically possible but faces enormous technical challenges (you'd have to edit thousands of copies per cell).

The broader implications extend beyond mitochondrial disease. MRT has proven that cytoplasmic transfer between eggs is technically feasible and compatible with healthy development. This opens doors to other applications—potentially including age-related infertility (where egg quality declines partly due to mitochondrial function).

The ethical debates will continue. Every new case, every outcome, every long-term follow-up will inform the conversation. We're in the early days of a technology that could reshape how we think about genetic inheritance.

The Deeper Question

Mitochondria are not us—they're our symbionts. They have their own genome, their own evolutionary history, their own lineage that we inherit from our mothers.

When we swap mitochondria, we're not changing what most people think of as identity—the traits encoded in nuclear DNA. We're changing which bacterial descendants live inside us. We're changing the power plant, not the building.

But the power plant matters. It's been with our lineage for two billion years. It's part of what makes us eukaryotes rather than bacteria. It's not nothing.

MRT forces us to confront what we mean by "genetic parent," by "inherited," by "identity." These words worked fine when inheritance followed clear patterns. Now we have to think more carefully.

The children born through MRT are healthy, living, growing people. They don't seem confused about who their parents are. They're not philosophical puzzles—they're kids.

But the questions they raise persist. What do we owe future generations? What risks are acceptable to prevent suffering? Where does medical treatment end and human enhancement begin? When is germline modification acceptable, and when is it not?

MRT is medicine. It's also the beginning of a conversation about who we are and who we might become.

Further Reading

- Craven, L., et al. (2010). "Pronuclear transfer in human embryos to prevent transmission of mitochondrial DNA disease." Nature. - Hyslop, L. A., et al. (2016). "Towards clinical application of pronuclear transfer to prevent mitochondrial DNA disease." Nature. - Nuffield Council on Bioethics. (2012). "Novel techniques for the prevention of mitochondrial DNA disorders: an ethical review." - Zhang, J., et al. (2017). "Live birth derived from oocyte spindle transfer to prevent mitochondrial disease." Reproductive BioMedicine Online.

This is Part 7 of the Mitochondria Mythos series. Next: "Synthesis: The Symbiont Within."

Comments ()