Mitophagy: Clearing Out Damaged Mitochondria

Your cells are eating themselves right now.

Not all of themselves—just the damaged parts. The broken organelles. The misfolded proteins. The accumulated debris that would otherwise gum up the works.

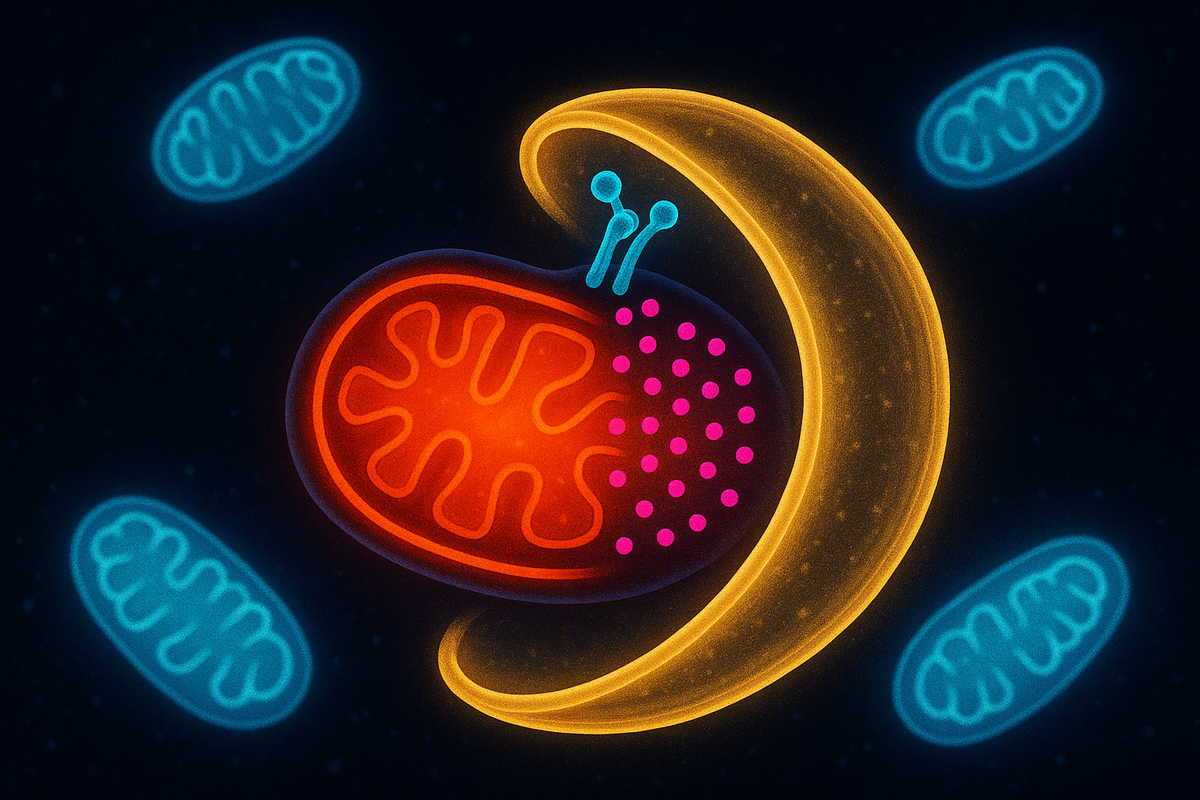

This process is called autophagy, from the Greek for "self-eating." And when cells specifically target damaged mitochondria for destruction, it's called mitophagy—mitochondrial autophagy.

It sounds destructive. It's actually essential for health. Without mitophagy, dysfunctional mitochondria accumulate, spewing reactive oxygen species, triggering inflammation, and dragging down cellular function. The ability to recognize, tag, and destroy damaged mitochondria is one of the key quality control systems that keeps you alive.

When mitophagy fails, diseases follow. Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, heart failure, cancer. The connection is becoming increasingly clear.

Your cells survive by selectively destroying parts of themselves. The power plants that malfunction have to go.

Why Mitochondria Need Quality Control

Mitochondria are dangerous.

They produce most of the cell's ATP—but the electron transport chain that generates ATP also generates reactive oxygen species. Superoxide. Hydrogen peroxide. Hydroxyl radicals. These molecules damage DNA, oxidize proteins, and degrade lipids.

Mitochondria are both the power plant and the source of pollution.

When a mitochondrion is healthy, it minimizes ROS production and the damage is manageable. Antioxidant systems neutralize what escapes. The cell maintains homeostasis.

But mitochondria accumulate damage over time. mtDNA mutations. Protein aggregates. Membrane damage. As a mitochondrion deteriorates, its ROS production increases and its ATP production decreases. A vicious cycle: more damage leads to more ROS, which leads to more damage.

A damaged mitochondrion is worse than useless—it's actively harmful. It makes less energy while producing more toxicity. The cell needs to identify these dysfunctional organelles and eliminate them before they poison the whole system.

Mitophagy is the cleanup crew. Find the broken power plants, wrap them up, and send them to the recycling center.

How Mitophagy Works

The basic process has several steps:

Step 1: Recognize the damaged mitochondrion. Something has to distinguish healthy from dysfunctional mitochondria. Multiple signals can trigger this recognition—loss of membrane potential, accumulation of misfolded proteins, or activation of specific stress sensors.

Step 2: Tag it for destruction. Once recognized, the damaged mitochondrion gets marked with molecular tags that say "eat me." Ubiquitin chains are the most common tags—they're recognized by the autophagy machinery.

Step 3: Wrap it in a membrane. An isolation membrane (phagophore) forms around the tagged mitochondrion, eventually closing to create a double-membraned vesicle called an autophagosome. The mitochondrion is now isolated from the rest of the cell.

Step 4: Fuse with a lysosome. The autophagosome fuses with a lysosome—an organelle filled with digestive enzymes. The contents are degraded, and the components (amino acids, lipids, nucleotides) are recycled.

This is selective autophagy. The cell isn't randomly digesting itself; it's targeting specific damaged components. Mitophagy receptors on the mitochondrial surface bind to autophagy machinery, ensuring that only the right mitochondria get destroyed.

PINK1 and Parkin: The Key Players

The most studied mitophagy pathway involves two proteins: PINK1 and Parkin. Mutations in the genes encoding these proteins cause familial Parkinson's disease.

Here's how the pathway works:

In healthy mitochondria: PINK1 (PTEN-induced kinase 1) is constantly imported into mitochondria and rapidly degraded inside. It never accumulates on the outer membrane. The mitochondrion looks normal to the cell.

In damaged mitochondria: When the mitochondrial membrane potential collapses (a sign of dysfunction), the import machinery fails. PINK1 can't get into the mitochondrion. Instead, it accumulates on the outer membrane, where it becomes stable and active.

PINK1 recruits Parkin: Accumulated PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin and activates Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Parkin then ubiquitinates proteins on the mitochondrial surface—coating the organelle with "eat me" signals.

Ubiquitin attracts autophagy receptors: Proteins like NDP52 and OPTN bind to the ubiquitin chains and recruit the autophagy machinery. The autophagosome forms around the damaged mitochondrion.

Destruction follows: The tagged mitochondrion is engulfed, delivered to lysosomes, and degraded.

This is an elegant damage-sensing system. Healthy mitochondria degrade PINK1, keeping it invisible. Damaged mitochondria can't import PINK1, causing it to accumulate and trigger destruction. The signal is the failure of normal function.

PINK1 is the sentinel. Parkin is the executioner. Together they maintain mitochondrial quality.

Parkinson's Disease Connection

The discovery of PINK1 and Parkin mutations in Parkinson's patients was a breakthrough.

Parkinson's disease is characterized by the death of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra—a brain region involved in movement control. The dying neurons accumulate protein aggregates called Lewy bodies, and patients progressively lose motor function.

Most Parkinson's is sporadic—no clear genetic cause. But about 10-15% of cases are familial, with identifiable mutations. PINK1 and PARK2 (the gene encoding Parkin) are two of the genes mutated in early-onset familial Parkinson's.

The implication: defective mitophagy causes neurodegeneration.

Dopaminergic neurons are particularly vulnerable. They have high energy demands (neurons are energetically expensive), they're exposed to dopamine metabolism byproducts (which generate ROS), and they have long axons that require extensive mitochondrial transport. If they can't clear damaged mitochondria, they accumulate dysfunction and eventually die.

The connection has been supported by animal models. Mice lacking PINK1 or Parkin develop mitochondrial abnormalities in neurons. Flies with these mutations show neurodegeneration. The pathway is evolutionarily conserved and functionally critical.

Parkinson's may be, at its core, a disease of mitochondrial quality control failure.

Beyond PINK1/Parkin

PINK1/Parkin is the best-understood mitophagy pathway, but it's not the only one.

Receptor-mediated mitophagy: Some mitochondrial outer membrane proteins can directly recruit autophagy machinery without ubiquitination. BNIP3, NIX, and FUNDC1 are examples. They contain motifs that bind LC3 (a key autophagy protein), enabling mitophagy through a simpler pathway.

Cardiolipin externalization: Cardiolipin is a lipid normally found only in the inner mitochondrial membrane. When mitochondria are damaged, cardiolipin can flip to the outer membrane, serving as an "eat me" signal recognized by LC3.

AMBRA1-mediated mitophagy: AMBRA1 can directly bind damaged mitochondria and recruit autophagy machinery, particularly during certain stress conditions.

Different pathways may operate in different cell types, under different conditions, or in response to different types of damage. The redundancy suggests mitophagy is important enough that evolution built multiple backup systems.

Mitophagy and Aging

Aging is associated with declining autophagy—including mitophagy.

Older organisms have: - Less autophagy activity overall - More dysfunctional mitochondria - Increased oxidative stress - More mtDNA mutations

The correlation is striking. The causation is harder to prove, but evidence is accumulating.

Enhancing autophagy extends lifespan in multiple model organisms. Caloric restriction—the most robust longevity intervention—activates autophagy. Rapamycin, which inhibits mTOR and thereby activates autophagy, extends mouse lifespan. The connection between autophagy and longevity is robust.

Specifically enhancing mitophagy is harder to test, but some experiments support its importance. Overexpressing PINK1 or Parkin can improve mitochondrial function in aged tissues. Drugs that enhance mitophagy are being explored as potential anti-aging interventions.

The logic is intuitive. If aging involves accumulating cellular damage, and mitophagy clears damaged mitochondria, then declining mitophagy should accelerate damage accumulation. Restoring it should slow the decline.

Aging may be partly a failure of quality control. The cleanup crews retire. The junk piles up.

Mitophagy in Disease

Beyond Parkinson's, defective mitophagy has been implicated in numerous conditions:

Alzheimer's disease: Accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria in neurons, impaired autophagy, and connections to amyloid and tau pathology. The relationship is complex but increasingly recognized.

Heart failure: The heart is the most metabolically active organ, packed with mitochondria. Cardiac mitophagy is essential for heart health. Defects contribute to cardiomyopathy and heart failure.

Metabolic diseases: Diabetes and obesity are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Impaired mitophagy in muscle, liver, and adipose tissue may contribute to insulin resistance.

Cancer: The relationship is paradoxical. Mitophagy can suppress cancer by clearing damaged mitochondria that might promote oncogenesis. But established tumors often upregulate mitophagy to survive metabolic stress. Context matters.

Infectious disease: Some pathogens target mitophagy pathways. Viruses may inhibit mitophagy to prevent their destruction. Bacteria may trigger mitophagy to evade immune detection. The battle between host and pathogen plays out on mitochondrial terrain.

Inflammatory diseases: Damaged mitochondria that escape mitophagy can release mtDNA into the cytoplasm. The immune system sees mtDNA as foreign (it looks bacterial, because it is) and triggers inflammation. Failed mitophagy fuels chronic inflammation.

Therapeutic Possibilities

If defective mitophagy causes disease, enhancing it might treat disease.

Several approaches are being explored:

Small molecule enhancers. Compounds that activate PINK1, enhance Parkin activity, or promote autophagy could boost mitophagy. Urolithin A, a metabolite produced by gut bacteria from pomegranate compounds, has shown mitophagy-enhancing effects in preclinical studies and is now in clinical trials.

NAD+ restoration. NAD+ boosters (NR, NMN) may enhance mitophagy indirectly by improving mitochondrial function and activating sirtuins, which regulate autophagy.

mTOR inhibitors. Rapamycin and its analogs activate autophagy by inhibiting mTOR, a nutrient-sensing pathway that suppresses autophagy when nutrients are abundant.

Exercise. Physical activity is one of the most potent autophagy activators known. Exercise increases mitophagy in muscle, clears dysfunctional mitochondria, and stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis to replace them. The combination—destroy the bad, build the new—is the ultimate mitochondrial renewal program.

Fasting. Nutrient deprivation activates autophagy. Intermittent fasting and caloric restriction enhance autophagy and mitophagy, which may contribute to their health benefits.

The drug pipeline is early-stage, but the lifestyle interventions—exercise, fasting—are available now. They're not specifically targeting mitophagy, but they activate it as part of broader adaptive responses.

The Balance: Too Little or Too Much

Mitophagy, like most biological processes, requires balance.

Too little mitophagy: Damaged mitochondria accumulate, ROS increases, cells become dysfunctional. This is the scenario in Parkinson's, aging, and many chronic diseases.

Too much mitophagy: If mitophagy is excessive, cells might destroy too many mitochondria, leaving themselves energy-starved. This can happen in some forms of stress or as a pathological response.

The cell constantly calibrates. Nutrient status, energy demands, stress signals, and damage levels all feed into the decision of how much mitophagy to run. The PINK1/Parkin pathway is sensitive to membrane potential—a direct readout of mitochondrial health. Receptor-mediated pathways respond to different signals.

Interventions need to enhance mitophagy when it's deficient without overshooting. This is one of the challenges in drug development—hitting the sweet spot of enhanced quality control without excessive destruction.

The Renewal Cycle

Mitophagy is only half the story. The other half is mitochondrial biogenesis—making new mitochondria.

The two processes are coupled. When mitophagy clears damaged mitochondria, biogenesis replaces them with fresh ones. The cell maintains its mitochondrial population not by preserving the same organelles forever but by constantly turning them over.

PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha) is the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Exercise, cold exposure, and caloric restriction all activate PGC-1α, stimulating the production of new mitochondria.

The healthy state is dynamic equilibrium: mitophagy removing the old and damaged, biogenesis generating the new. Aging and disease shift this balance—less clearance, less replacement, accumulating dysfunction.

Mitochondria aren't permanent fixtures. They're continuously replaced. Health depends on keeping the renewal cycle turning.

Coherence Through Destruction

The AToM framework sees coherence as central to meaning and function. Mitophagy is coherence maintenance at the cellular level.

A cell with damaged mitochondria is losing coherence. Energy production falters. ROS increases. Function degrades. The system drifts toward disorder.

Mitophagy restores coherence by removing the incoherent elements. It's pruning—cutting away what doesn't work so the whole can function. The cell maintains its identity and function by selectively destroying parts of itself.

This is a deep pattern. Organisms maintain themselves through continuous self-modification. Neurons prune synapses to sharpen circuits. Immune systems delete self-reactive cells. Bodies rebuild tissues. Life persists by changing.

Coherence is not stasis. It's dynamic stability through continuous renewal.

Further Reading

- Youle, R. J., & Narendra, D. P. (2011). "Mechanisms of mitophagy." Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. - Pickles, S., Vigié, P., & Bhatt, R. S. (2018). "Mitophagy and Quality Control Mechanisms in Mitochondrial Maintenance." Current Biology. - Harper, J. W., Ordureau, A., & Heo, J. M. (2018). "Building and decoding ubiquitin chains for mitophagy." Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. - Lemasters, J. J. (2005). "Selective Mitochondrial Autophagy, or Mitophagy, as a Targeted Defense Against Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Aging." Rejuvenation Research.

This is Part 5 of the Mitochondria Mythos series. Next: "The Warburg Effect: Cancer's Metabolic Signature."

Comments ()