Modular Arithmetic: When Numbers Wrap Around

It's 11 o'clock. Add 3 hours. What time is it?

2 o'clock.

Not 14 o'clock. The numbers wrap around. After 12 comes 1. This is modular arithmetic—arithmetic where numbers cycle back to the beginning after reaching a limit.

You use it every day: clocks (12-hour and 24-hour), calendars (days of the week cycle every 7 days), angles (360° = 0°).

But modular arithmetic isn't just clock math. It's the foundation of:

- Cryptography: RSA encryption, Diffie-Hellman key exchange, elliptic curve crypto

- Hash functions: Distributing data evenly across buckets

- Error detection: Check digits in credit cards, ISBNs, bar codes

- Random number generation: Pseudorandom sequences

- Computer science: Circular buffers, hash tables, ring networks

The math of "wrapping around" turns out to be one of the most powerful tools in discrete mathematics.

The Definition

Modular arithmetic is arithmetic where numbers wrap around after reaching a value called the modulus.

Notation: a ≡ b (mod m)

Read: "a is congruent to b modulo m"

Meaning: a and b have the same remainder when divided by m.

Example:

- 17 ≡ 5 (mod 12) because 17 = 1×12 + 5 and 5 = 0×12 + 5 (both leave remainder 5)

- 23 ≡ 3 (mod 10) because 23 = 2×10 + 3 and 3 = 0×10 + 3

Equivalently: a ≡ b (mod m) if m divides (a - b).

Example: 17 ≡ 5 (mod 12) because 12 divides (17 - 5) = 12.

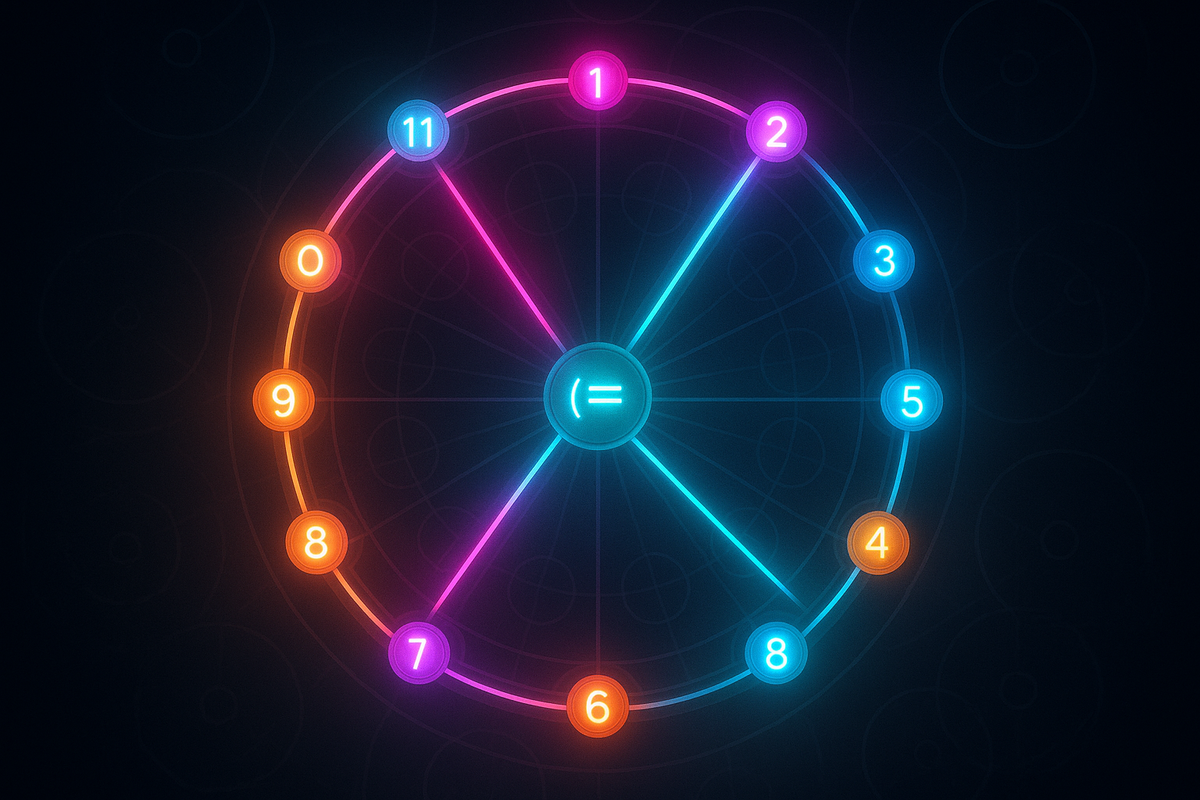

Clock Arithmetic

The classic example: A 12-hour clock.

11 + 3 ≡ 2 (mod 12) 8 + 7 ≡ 3 (mod 12) 10 - 11 ≡ 11 (mod 12) (going backward wraps to 11)

Why it works: Time is periodic. After 12 hours, you're back to hour 0 (or 12 in 12-hour notation).

Modular arithmetic formalizes this cyclic behavior.

Operations in Modular Arithmetic

Addition

(a + b) mod m = ((a mod m) + (b mod m)) mod m

Example: (17 + 23) mod 10 = (7 + 3) mod 10 = 10 mod 10 = 0

Subtraction

(a - b) mod m = ((a mod m) - (b mod m)) mod m

If the result is negative, add m.

Example: (5 - 8) mod 12 = -3 mod 12 = (-3 + 12) mod 12 = 9 mod 12

Multiplication

(a × b) mod m = ((a mod m) × (b mod m)) mod m

Example: (17 × 23) mod 10 = (7 × 3) mod 10 = 21 mod 10 = 1

Exponentiation

aⁿ mod m can be computed efficiently using modular exponentiation.

Naive approach (compute aⁿ, then mod m) fails for large n—intermediate values explode.

Fast method (repeated squaring): Compute a¹, a², a⁴, a⁸, ... (mod m), then combine based on binary representation of n.

Example: Compute 7¹⁹ mod 13

- 19 in binary: 10011

- 7¹ mod 13 = 7

- 7² mod 13 = 49 mod 13 = 10

- 7⁴ mod 13 = (7²)² mod 13 = 100 mod 13 = 9

- 7⁸ mod 13 = (7⁴)² mod 13 = 81 mod 13 = 3

- 7¹⁶ mod 13 = (7⁸)² mod 13 = 9 mod 13 = 9

- Combine: 7¹⁹ = 7¹⁶ × 7² × 7¹ = 9 × 10 × 7 = 630 mod 13 = 6

Runs in O(log n) time instead of O(n). Essential for cryptography (exponents can be hundreds of digits).

Modular Inverses

In regular arithmetic, the inverse of a (for multiplication) is 1/a. In modular arithmetic, the inverse of a (mod m) is a number b such that:

a × b ≡ 1 (mod m)

Example: What's the inverse of 3 (mod 7)?

Try: 3 × 1 = 3 ≠ 1 3 × 2 = 6 ≠ 1 3 × 3 = 9 ≡ 2 (mod 7) 3 × 4 = 12 ≡ 5 (mod 7) 3 × 5 = 15 ≡ 1 (mod 7) ✓

So 5 is the inverse of 3 (mod 7). Written: 3⁻¹ ≡ 5 (mod 7).

Key fact: a has an inverse mod m if and only if gcd(a, m) = 1 (a and m are coprime).

If m is prime, every number 1 ≤ a < m has an inverse.

Finding inverses: Use the Extended Euclidean Algorithm to compute inverses efficiently.

Why inverses matter: Division in modular arithmetic is multiplication by the inverse. a / b (mod m) = a × b⁻¹ (mod m).

Cryptography depends on modular inverses (RSA decryption, elliptic curves, etc.).

Fermat's Little Theorem

If p is prime and a is not divisible by p:

aᵖ⁻¹ ≡ 1 (mod p)

Example: p = 7, a = 3 3⁶ mod 7 = 729 mod 7 = 1 ✓

Corollary: aᵖ ≡ a (mod p) for any a.

Why it matters:

- Primality testing: If aⁿ⁻¹ ≢ 1 (mod n) for some a, then n is composite. (Fermat's test—not definitive but fast.)

- Computing inverses: a⁻¹ ≡ aᵖ⁻² (mod p) when p is prime. (From a × aᵖ⁻² = aᵖ⁻¹ ≡ 1.)

Fermat's Little Theorem is foundational in number theory and cryptography.

Euler's Theorem (Generalization)

For any a and m where gcd(a, m) = 1:

a^φ(m) ≡ 1 (mod m)

Where φ(m) is Euler's totient function—the count of numbers ≤ m that are coprime to m.

Example: φ(9) = 6 (numbers coprime to 9: 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8).

If p is prime, φ(p) = p - 1 (all numbers 1 to p-1 are coprime to p). Euler's theorem reduces to Fermat's Little Theorem for primes.

Why it matters: Euler's theorem is the basis of RSA encryption.

RSA Cryptography

RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman) is the most widely used public-key cryptosystem. It's built on modular arithmetic.

Key generation:

- Choose two large primes p and q

- Compute n = p × q

- Compute φ(n) = (p-1)(q-1)

- Choose e coprime to φ(n) (commonly e = 65537)

- Compute d = e⁻¹ (mod φ(n)) using Extended Euclidean Algorithm

- Public key: (e, n). Private key: (d, n).

Encryption: Ciphertext c = mᵉ (mod n), where m is the message.

Decryption: Message m = cᵈ (mod n).

Why it works: c^d = (mᵉ)^d = m^{ed} (mod n).

Since d = e⁻¹ (mod φ(n)), we have ed ≡ 1 (mod φ(n)), so ed = k×φ(n) + 1 for some k.

By Euler's theorem: m^{φ(n)} ≡ 1 (mod n) (assuming gcd(m, n) = 1).

So m^{ed} = m^{k×φ(n) + 1} = (m^{φ(n)})^k × m ≡ 1^k × m = m (mod n).

Decryption recovers the original message.

Security: Factoring n = p × q is hard for large n. Without p and q, you can't compute φ(n), so you can't find d. The security relies on the difficulty of factoring—a number theory problem intimately tied to modular arithmetic.

Chinese Remainder Theorem

Problem: Solve a system of congruences:

- x ≡ a₁ (mod m₁)

- x ≡ a₂ (mod m₂)

- ...

- x ≡ aₖ (mod mₖ)

Where m₁, m₂, ..., mₖ are pairwise coprime.

Chinese Remainder Theorem (CRT): There exists a unique solution modulo M = m₁ × m₂ × ... × mₖ.

Example:

- x ≡ 2 (mod 3)

- x ≡ 3 (mod 5)

- x ≡ 2 (mod 7)

M = 3 × 5 × 7 = 105.

Use CRT formula (construction via Bézout's identity and modular inverses): x ≡ 23 (mod 105).

(Verify: 23 mod 3 = 2 ✓, 23 mod 5 = 3 ✓, 23 mod 7 = 2 ✓)

Applications:

- Fast modular arithmetic: Break large modulus computations into smaller coprime moduli, compute separately, combine via CRT (faster).

- Secret sharing: Split a secret among multiple parties using CRT.

- Error correction: Redundant residue number systems.

Hashing and Hash Tables

Hash functions map data to a fixed range (often modulo a prime).

Example: Hash function h(key) = key mod m.

If you have 1000 buckets (m = 1000), each key gets mapped to a bucket 0-999.

Why modular arithmetic? Ensures uniform distribution (if m is prime or carefully chosen).

Collision resolution: When two keys hash to the same bucket, use chaining (linked lists) or probing (search for next empty bucket).

Modular arithmetic underpins hash tables—the data structure powering dictionaries, sets, database indices, caches.

Check Digits

Credit card numbers, ISBNs, barcodes use check digits to detect errors.

Example: ISBN-10 uses modular arithmetic mod 11.

ISBN: 0-306-40615-2

Check digit calculation: Σ (10-i) × digit_i (mod 11) = 0

If the sum isn't 0 mod 11, the number is invalid (typo detected).

Why modular arithmetic? Wrapping around provides error-checking structure. Single-digit errors and transpositions often change the checksum.

Pseudorandom Number Generators

Linear congruential generator (LCG): X_{n+1} = (a × X_n + c) mod m

Example: X_0 = 1, a = 5, c = 3, m = 16

- X_1 = (5×1 + 3) mod 16 = 8

- X_2 = (5×8 + 3) mod 16 = 43 mod 16 = 11

- X_3 = (5×11 + 3) mod 16 = 58 mod 16 = 10

- ...

The sequence cycles (period depends on choice of a, c, m). LCGs are fast but not cryptographically secure.

Better PRNGs use more sophisticated modular arithmetic (Mersenne Twister, etc.).

Cyclic Groups

In modular arithmetic mod m, the set {0, 1, 2, ..., m-1} under addition forms a cyclic group.

Example: mod 5: {0, 1, 2, 3, 4}

- 2 + 3 ≡ 0 (mod 5)

- 4 + 4 ≡ 3 (mod 5)

Multiplicative group: For m prime, {1, 2, ..., m-1} under multiplication mod m forms a cyclic group.

Generators: An element g is a generator if repeatedly multiplying g generates all elements.

Example: mod 7, g = 3:

- 3¹ = 3

- 3² = 9 ≡ 2 (mod 7)

- 3³ = 27 ≡ 6 (mod 7)

- 3⁴ = 81 ≡ 4 (mod 7)

- 3⁵ = 243 ≡ 5 (mod 7)

- 3⁶ = 729 ≡ 1 (mod 7)

3 generates {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}—all non-zero elements mod 7.

Why it matters: Cyclic groups underpin Diffie-Hellman key exchange and discrete logarithm problems in cryptography.

Discrete Logarithm Problem

Given g, h, and m, find x such that g^x ≡ h (mod m).

Example: g = 3, h = 6, m = 7. Find x where 3^x ≡ 6 (mod 7).

Try: 3¹ = 3, 3² = 2, 3³ = 6 ✓. So x = 3.

For small m, brute force works. For large m (hundreds of digits), no efficient algorithm is known. This hardness secures Diffie-Hellman and elliptic curve cryptography.

Relation to factoring: Both discrete log and factoring are hard number theory problems. Quantum computers (Shor's algorithm) can solve both efficiently, threatening current cryptography.

Applications in Computer Science

Circular buffers: Queue wraps around when reaching end of array. Index = (start + i) mod size.

Round-robin scheduling: Processes scheduled in cyclic order. Next process = (current + 1) mod n.

Hash tables: Hash function h(key) = key mod m distributes keys across buckets.

Network protocols: Sequence numbers wrap around (TCP uses modular arithmetic for packet ordering).

Graphics: Angles wrap (360° ≡ 0°). Rotations use mod 360 or mod 2π.

Why Wrapping Around Matters

Modular arithmetic seems like a quirk—numbers resetting after a limit. But it's fundamental:

- Finite structures: Computers have finite memory, finite registers. Modular arithmetic models overflow behavior.

- Cyclic phenomena: Time, angles, periodic processes—nature is full of cycles.

- Number theory: Divisibility, primes, factorization—modular arithmetic reveals deep structure.

- Cryptography: The hardness of modular problems (factoring, discrete log) secures digital communication.

The mathematics of "wrapping around" isn't a simplification. It's a window into the structure of numbers, the behavior of finite systems, and the foundation of secure computation.

Further Reading

- Burton, David M. Elementary Number Theory. McGraw-Hill, 7th edition, 2010. (Modular arithmetic, Fermat, Euler)

- Rosen, Kenneth H. Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications. McGraw-Hill, 8th edition, 2018. (Modular arithmetic, RSA)

- Koblitz, Neal. A Course in Number Theory and Cryptography. Springer, 2nd edition, 1994. (Cryptographic applications)

- Cormen, Thomas H., et al. Introduction to Algorithms. MIT Press, 4th edition, 2022. (Modular exponentiation, hash functions)

This is Part 11 of the Discrete Mathematics series, exploring the foundational math of computer science, algorithms, and computational thinking. Next: "Discrete Math Synthesis — The Foundation of Computer Science."

Part 11 of the Discrete Mathematics series.

Previous: Boolean Algebra: The Mathematics of True and False Next: Synthesis: Discrete Math as the Foundation of Computer Science

Comments ()