mRNA Vaccines: How COVID Changed Everything

In 2005, Katalin Karikó was demoted.

She'd been working on mRNA therapeutics at the University of Pennsylvania for years—decades, really. The idea was simple: if you could deliver mRNA to cells, you could get them to produce any protein you wanted. Medicine would become programmable. You'd be writing prescriptions in nucleotides.

But it kept not working. When you inject synthetic mRNA into the body, the immune system freaks out. The mRNA gets destroyed before it can do anything useful, and the inflammatory response can be dangerous. Grant applications were rejected. Papers were ignored. The university decided she wasn't faculty material.

So they demoted her. Stripped her tenure track. Cut her salary. In the academic hierarchy, she was functionally nobody—a researcher without a lab, without funding, without institutional support, plugging away at a problem everyone else had given up on.

Fifteen years later, her work saved millions of lives and she won the Nobel Prize.

The mRNA vaccine story isn't just about science. It's about the structure of science—what gets funded, who gets heard, and how breakthroughs happen despite institutions, not because of them.

The Problem Nobody Wanted to Solve

The idea of using mRNA as a therapeutic agent goes back to the 1990s. Researchers demonstrated you could inject mRNA into mouse muscle and get the cells to produce protein from it. Proof of concept achieved. Paper published. Problem solved.

Except not really.

Synthetic mRNA triggers an immune response. The body has evolved sophisticated sensors—toll-like receptors, among others—that detect foreign RNA and sound the alarm. This made evolutionary sense: viral infections often involve foreign RNA, so treating RNA as a threat is a reasonable defensive strategy.

But it meant that therapeutic mRNA caused inflammation, got degraded quickly, and often didn't produce much protein before being destroyed. The approach seemed to have a fundamental ceiling.

Most researchers moved on. Other delivery mechanisms seemed more promising. Gene therapy using viral vectors was getting all the attention. mRNA was a scientific curiosity, a good idea that didn't quite work.

Karikó didn't move on. She kept asking: why does synthetic mRNA trigger the immune response? And can we make it stop?

The Karikó-Weissman Discovery

In the early 2000s, Karikó met Drew Weissman at a photocopier. (Science often works this way. The most consequential collaborations form by accident.) Weissman was studying vaccines and immunology. Karikó knew mRNA. They started talking.

Together, they figured out the key insight: natural mRNA contains chemical modifications. The body's own mRNA has nucleosides like pseudouridine and methylated bases that synthetic mRNA typically lacks. And those modifications are what keeps the immune system calm.

When you inject synthetic mRNA with standard nucleosides, the toll-like receptors recognize it as foreign—potentially viral—and trigger inflammation. But when you substitute modified nucleosides—when you make synthetic mRNA that looks like natural mRNA—the immune system relaxes.

Their 2005 paper, published in Immunity, demonstrated that mRNA containing pseudouridine didn't trigger the inflammatory response. The immune system essentially ignored it. And because it wasn't being attacked, it lasted longer in cells and produced more protein.

This was the breakthrough. Not a new technology. A tweak. A modification that made the technology actually work.

The paper got about 100 citations in its first five years. Not obscure, but not earthshaking either. The field remained small. The academic establishment remained skeptical. Karikó had been right—and nobody particularly cared.

The Delivery Problem

Making mRNA that doesn't trigger inflammation was step one. Step two was getting it into cells.

mRNA is fragile. It's a long, single-stranded molecule that enzymes everywhere want to destroy. Injecting naked mRNA into the body is like dropping a laptop into a swimming pool—the information might technically still exist, but good luck accessing it.

You need packaging. Something that protects the mRNA in the bloodstream and helps it get inside cells where it can actually be read.

The solution that emerged: lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). Tiny bubbles of fat that encapsulate the mRNA, protecting it from degradation and fusing with cell membranes to release their cargo inside. The technology had been in development for decades—originally for other purposes—but it turned out to be exactly what mRNA needed.

This wasn't one lab's work. It was the accumulation of advances in lipid chemistry, nanoparticle engineering, and drug delivery. Companies like Arbutus Biopharma held key patents. Researchers at dozens of institutions contributed pieces. By the mid-2010s, the pieces were in place.

Modified mRNA + lipid nanoparticle delivery = a platform that could actually work.

BioNTech and Moderna: The Startups

In 2008, two companies were founded that would eventually make the mRNA vaccines that reached billions of arms.

Moderna was founded by a team including Derrick Rossi, a stem cell biologist who'd read the Karikó-Weissman papers and realized the implications. The name is a portmanteau of "modified RNA." The company raised enormous amounts of venture capital—over $2 billion before having any product on the market—betting that mRNA could become a platform for therapeutics and vaccines.

BioNTech was founded by Ugur Sahin and Özlem Türeci, a husband-and-wife team in Germany. Their original focus was cancer immunotherapy—using mRNA to teach the immune system to recognize and attack tumor cells. Vaccines came later.

Both companies spent years in the wilderness. Neither had an approved product. The technology kept promising but never quite delivering. The pipeline had candidates for cancer, rare genetic diseases, infectious diseases—but nothing had crossed the finish line.

Then 2020 happened.

11 Months

On January 10, 2020, Chinese scientists published the genetic sequence of a new coronavirus. By January 13, Moderna had designed an mRNA vaccine candidate. BioNTech started work around the same time.

Design is the easy part. The beauty of mRNA is that once you have your platform, targeting a new pathogen is mostly computational. You identify the protein you want the immune system to recognize—for SARS-CoV-2, the spike protein—sequence the gene, reverse-engineer the mRNA sequence that would code for it, and synthesize it. Days, not months.

Manufacturing is harder. Clinical trials are harder. Regulatory approval is harder. But those things can be paralyzed by bureaucracy or accelerated by necessity.

COVID provided necessity.

By March, both vaccines were in Phase 1 trials. By July, Phase 3 trials with tens of thousands of participants. By November, efficacy data: Pfizer-BioNTech's vaccine was 95% effective at preventing symptomatic COVID-19. Moderna's was 94%.

By December, the FDA issued emergency use authorizations. Less than a year from genetic sequence to injection.

The fastest vaccine development in history. By a factor of several.

The previous record holder was the mumps vaccine in the 1960s—about four years. Most vaccines take a decade or more. The mRNA vaccines compressed that timeline by an order of magnitude, not through recklessness but through parallel processing: running steps simultaneously that are usually done sequentially, manufacturing doses while trials were still ongoing, having regulatory agencies review data in real-time rather than waiting for final submissions.

The platform that nobody believed in saved millions of lives in a matter of months.

Why It Worked

Let's be precise about what the vaccines do.

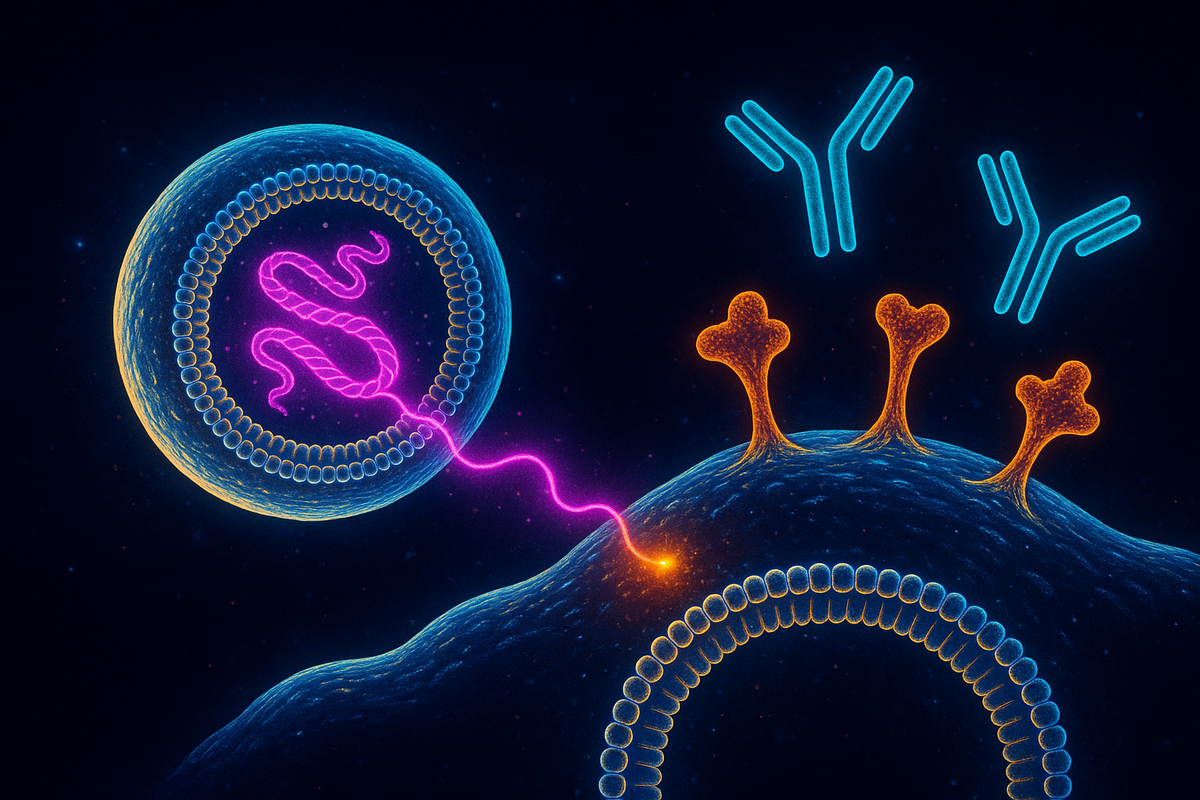

You get an injection of lipid nanoparticles containing mRNA encoding the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. The nanoparticles fuse with cells—mostly at the injection site and in nearby lymph nodes. The cells take up the mRNA and translate it, producing spike protein.

The spike protein triggers an immune response. Your body makes antibodies against it, trains T cells to recognize it, and creates memory cells for future encounters. When you later encounter the actual virus, your immune system already knows what to look for.

The mRNA itself doesn't integrate into your DNA—it can't, lacking the enzymes required for that process. It gets degraded within days, having served its purpose. What remains is immunological memory.

This is why mRNA vaccines could be developed so fast. The platform was already validated. Only the cargo—the specific mRNA sequence—needed to change. Compare to traditional vaccine development, where each new vaccine requires developing new production processes, new quality controls, new manufacturing at scale. mRNA standardizes all that. The factory stays the same; only the instructions change.

mRNA vaccines aren't just vaccines. They're programmable vaccine factories you temporarily install in your cells.

Katalin Karikó's Vindication

In 2023, Karikó and Weissman won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

The Nobel Committee cited their discovery of nucleoside modifications—the work that was done in the early 2000s, that the University of Pennsylvania responded to by demoting Karikó. The committee explicitly noted that their research "was critical for the development of effective mRNA vaccines."

Karikó's story has become a parable about scientific perseverance. Twenty years of obscurity. Funding rejected. Tenure denied. Salary cut. And then: proof that she was right all along, in the most dramatic possible way.

But there's a darker reading. The system failed. The mechanisms that are supposed to identify important research and support it—peer review, grant funding, tenure committees—looked at Karikó's work and said no. Not once, but repeatedly, over decades.

She persisted anyway. But how many other Katalin Karikós gave up? How many important ideas died because the researchers pursuing them ran out of funding, or couldn't get promoted, or needed to feed their families?

The mRNA vaccine success story is also a scientific infrastructure failure story. We got lucky. Karikó happened to be stubborn enough, and BioNTech and Moderna happened to have enough venture capital runway, and a pandemic happened to create urgency that finally matched the technology's potential.

We should not need planetary emergencies to fund important research.

Beyond COVID

The COVID vaccines were a proof of concept for something bigger.

If mRNA can teach your immune system to recognize a viral spike protein, it can teach your immune system to recognize other things too. Cancer cells that express abnormal proteins. Cells infected with HIV or tuberculosis. Any target you can encode in nucleotides.

Cancer vaccines are already in clinical trials. The idea: sequence a patient's tumor, identify proteins that are specific to that tumor (and not normal cells), design mRNAs encoding those proteins, inject them, and train the immune system to hunt down cancer cells with surgical precision. BioNTech and Moderna both have programs. Early results are promising.

HIV vaccines have failed for forty years because the virus mutates too fast and hides too well. mRNA's flexibility—the ability to update the vaccine sequence quickly—might finally make a broadly protective HIV vaccine possible.

Flu vaccines could become more effective if they're designed and manufactured each season using mRNA rather than the egg-based production that's been standard for decades.

Personalized medicine becomes real. If you can sequence a pathogen or a tumor and have a vaccine candidate within days, medicine becomes responsive in ways it never has been.

The platform is general. The applications are legion. COVID was the emergency that proved it worked. Now comes the expansion.

The Limits

mRNA isn't magic. It has real constraints.

Stability remains a challenge. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine required ultra-cold storage (-70°C initially) because the lipid nanoparticles are fragile. Moderna's formulation was more stable but still required freezing. This creates logistical nightmares in places without cold chain infrastructure.

Duration of response varies. mRNA vaccines produce strong initial immunity, but boosters are often needed. Whether this is a fundamental limitation or something that can be engineered away remains unclear.

Manufacturing scale hit ceilings during COVID. Producing billions of doses of an entirely new class of medicine tested the limits of global pharmaceutical infrastructure. Companies had to build new facilities, train new workers, establish new supply chains—all during a pandemic.

Cost is nontrivial. mRNA vaccines aren't cheap to produce, though they're cheaper than some alternatives and may become cheaper at scale.

The immune system is complicated. Not everyone responds to mRNA vaccines the same way. Some people get robust, durable protection; others need more doses. Optimizing this for different populations and different diseases is an ongoing challenge.

But these are engineering problems, not fundamental barriers. The science works. Now comes the optimization.

The Structure of Breakthroughs

The mRNA vaccine story teaches something about how breakthroughs actually happen.

It wasn't a flash of genius. It was decades of incremental work, much of it ignored or undervalued, coming together when circumstances demanded it. Karikó and Weissman's modification discovery. LNP delivery technology from multiple labs. Startup companies willing to bet on an unproven platform. A pandemic that created both need and funding.

Breakthroughs look sudden from outside. From inside, they're the slow accumulation of solutions waiting for the right problem.

The lesson isn't "trust the system"—the system repeatedly failed. The lesson is that important ideas often persist despite institutions, carried forward by stubborn individuals and contrarian funders, ready to emerge when circumstances finally align.

We can't predict when circumstances will align. But we can keep funding the stubborn individuals. We can tolerate research that doesn't fit current fashions. We can remember that the ideas that look useless today might save millions of lives tomorrow.

Katalin Karikó was demoted in 2005 for working on mRNA.

In 2020, her work saved the world.

Further Reading

- Karikó, K., & Weissman, D. (2005). "Suppression of RNA Recognition by Toll-like Receptors." Immunity. - Pardi, N., Hogan, M. J., Porter, F. W., & Weissman, D. (2018). "mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology." Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. - Kolata, G. (2021). "Kati Karikó Helped Shield the World From the Coronavirus." New York Times. - The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2023. NobelPrize.org.

This is Part 2 of the RNA Renaissance series. Next: "Epitranscriptomics: RNA's Own Epigenetic Layer."

Comments ()