Natural Logarithm: Why ln Uses Base e

The natural logarithm is what you get when you measure continuous growth.

If you want to know how many doublings, use log₂. If you want to know how many powers of 10, use log₁₀. If you want to know how much continuous growth, use ln.

The "natural" in natural logarithm means: this is the base that calculus prefers. It's not natural for humans (who like base 10) or computers (who like base 2). It's natural for mathematics itself.

The Definition

ln(x) = logₑ(x)

The natural log is the logarithm base e, where e ≈ 2.71828...

ln(e) = 1, because e¹ = e. ln(1) = 0, because e⁰ = 1. ln(eˣ) = x, because the log undoes the exponential.

Why e Is Special

The number e is the base that makes calculus clean:

d/dx(eˣ) = eˣ

No other exponential has this property. For 2ˣ or 10ˣ, the derivative includes an extra constant.

The inverse relationship:

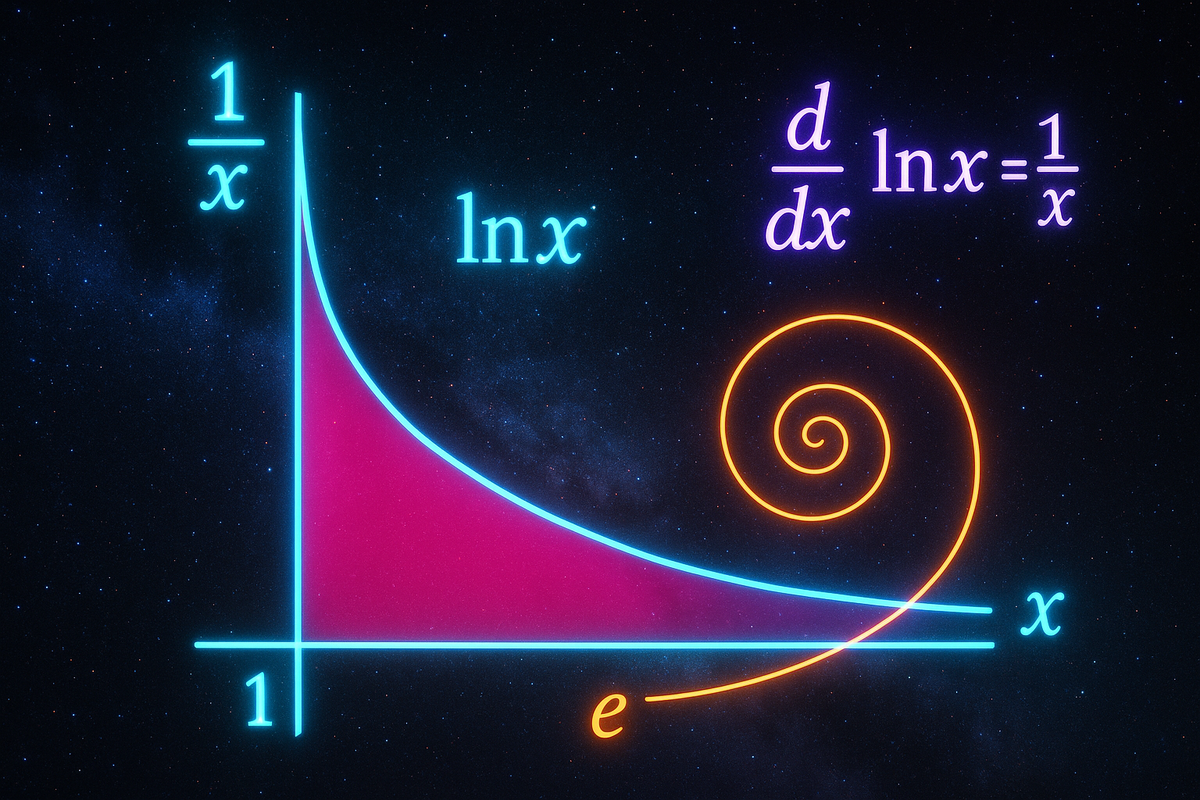

d/dx(ln x) = 1/x

This is the simplest possible derivative for a logarithm. No base-dependent constants. Just 1/x.

And for integrals:

∫(1/x)dx = ln|x| + C

The antiderivative of 1/x is the natural log. This is unique—no other logarithm works this cleanly.

The Graph

y = ln(x) has these features:

- Domain: x > 0

- Range: all real numbers

- Passes through (1, 0)

- Passes through (e, 1) ≈ (2.718, 1)

- Increases slowly, ever more slowly

- Concave down everywhere

- Vertical asymptote at x = 0

Compare to y = eˣ: they're mirror images across the line y = x. Where eˣ explodes upward, ln(x) creeps rightward.

Key Values

| x | ln(x) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1/e ≈ 0.368 | -1 | e⁻¹ |

| 1 | 0 | Always |

| e ≈ 2.718 | 1 | Definition |

| e² ≈ 7.389 | 2 | |

| 10 | 2.303 | Conversion factor to log₁₀ |

| 100 | 4.605 |

Notice: ln(10) ≈ 2.303. This number appears whenever you convert between natural and common logs.

Properties

All log rules apply, just with base e:

ln(xy) = ln(x) + ln(y) ln(x/y) = ln(x) - ln(y) ln(xⁿ) = n·ln(x) ln(1) = 0 ln(e) = 1

And the inverse relationships:

ln(eˣ) = x for all x e^(ln x) = x for x > 0

Why "Natural"?

Consider continuous compound interest at rate r:

A = Pe^(rt)

To find how long until your money doubles:

2P = Pe^(rt) 2 = e^(rt) ln(2) = rt t = ln(2)/r

The natural log appears naturally when solving continuous growth problems.

Similarly, for radioactive decay with half-life T:

N = N₀e^(-λt) λ = ln(2)/T

The decay constant λ involves ln(2). The natural log is baked into continuous exponential processes.

Calculating with ln

Finding ln(x):

Most calculators have a dedicated ln button. For mental estimates:

- ln(1) = 0

- ln(2) ≈ 0.693

- ln(3) ≈ 1.099

- ln(10) ≈ 2.303

- ln(e) = 1

Useful approximation: ln(1 + x) ≈ x for small x.

Finding x from ln(x):

If ln(x) = k, then x = eᵏ.

If ln(x) = 2, then x = e² ≈ 7.389.

The Natural Log and Calculus

The definite integral of 1/t from 1 to x equals ln(x):

ln(x) = ∫₁ˣ (1/t) dt

This is sometimes used as the definition of ln. The area under 1/t from 1 to x is ln(x).

This definition explains why:

- ln(1) = 0 (no area from 1 to 1)

- ln(x) < 0 for x < 1 (area runs "backward")

- ln'(x) = 1/x (by the fundamental theorem of calculus)

Converting Between Bases

ln(x) = log₁₀(x) × ln(10) ≈ 2.303 × log(x)

log₁₀(x) = ln(x) / ln(10) ≈ ln(x) / 2.303

The factor ln(10) ≈ 2.303 converts between natural and common logs.

For base 2:

log₂(x) = ln(x) / ln(2) ≈ ln(x) / 0.693 ≈ 1.443 × ln(x)

Applications

Continuous growth: A = A₀e^(kt) ↔ ln(A/A₀) = kt

Carbon dating: Age = -ln(remaining fraction) × (half-life / ln(2))

Complexity analysis: O(log n) often means O(ln n) in theoretical CS.

Information theory: Entropy H = -∑ pᵢ ln(pᵢ) uses natural log for theoretical elegance.

Physics: The Boltzmann equation S = k ln(W) defines entropy with natural log.

Statistics: Maximum likelihood involves ln because products become sums.

Why Use ln Instead of log?

When should you use natural log vs. common log?

Use ln when:

- Doing calculus (derivatives, integrals)

- Working with continuous growth/decay

- Following physics/chemistry conventions

- Dealing with e or expressions involving e

Use log (base 10) when:

- Measuring orders of magnitude

- Working with decibels, pH, Richter scale

- Matching human intuition about "10 times bigger"

- Following engineering conventions

Use log₂ when:

- Counting doublings

- Working with binary/computer science

- Measuring bits of information

The Essential Insight

The natural logarithm is natural because it makes calculus work smoothly.

d/dx(ln x) = 1/x

No constants, no conversions, just the simplest possible relationship.

This simplicity isn't arbitrary. It emerges because e is defined as the base where (d/dx)bˣ = bˣ. The natural log is the inverse of the natural exponential, and together they form the cleanest pair in calculus.

When growth or decay is continuous—not in discrete steps but flowing smoothly—the natural logarithm is the measuring stick.

Part 4 of the Logarithms series.

Previous: Common Logarithms: Base 10 and Scientific Notation Next: Change of Base Formula: Converting Between Logarithms

Comments ()