Natural Transformations: When Different Paths Lead to the Same Place

Different therapeutic approaches—psychoanalysis, CBT, EMDR—achieve equivalent healing through distinct mechanisms. Category theory's natural transformations explain how fundamentally different paths lead to the same place.

Natural Transformations: When Different Paths Lead to the Same Place

Formative Note

This essay represents early thinking by Ryan Collison that contributed to the development of A Theory of Meaning (AToM). The canonical statement of AToM is defined here.

Different therapies work.

Psychoanalysis works for some people. Cognitive-behavioral therapy works. EMDR works. Somatic experiencing works. IFS works. Even apparently opposite approaches—insight-oriented versus behavioral, top-down versus bottom-up—can produce genuine healing.

How is this possible? If these approaches are doing different things, how can they achieve similar results? And if they're achieving similar results, in what sense are they different?

One answer is that they're all doing the same thing at different levels of description. The behavioral intervention changes brain states. The insight intervention changes brain states. The somatic intervention changes brain states. Different paths, same destination.

But this answer is unsatisfying. The paths really are different. The experience of each therapy is different. The mechanisms proposed are different. Saying "they all change brain states" collapses important distinctions. It's true but unhelpful.

Category theory offers a more precise answer: natural transformations. Different functors—different ways of mapping structure from one domain to another—can be systematically related. They accomplish similar structural work through different routes. Understanding the relationship between the routes is understanding how different paths can lead to the same place while remaining genuinely different paths.

This concept matters beyond therapy. Whenever you encounter multiple approaches to the same problem, multiple ways of understanding the same phenomenon, multiple routes to the same destination, natural transformations are lurking. They're the mathematics of equivalence-with-difference.

The Setup: Multiple Functors

Recall that a functor is a structure-preserving map between categories. The functor from neural states to psychological states maps neural configurations to mental states and neural transitions to psychological transitions, preserving composition—the pattern of how things chain.

But there isn't just one such functor. There could be many different functors between the same categories. Different ways of mapping neural to psychological. Different ways of mapping individual to relational. Different ways of translating structure from one domain to another.

Consider two functors F and G, both going from category C to category D.

F maps every object in C to some object in D, and every arrow in C to some arrow in D. G does the same. But F and G might make different choices. For object A in C, F(A) might be different from G(A). For arrow f in C, F(f) might be different from G(f).

Both functors are legitimate. Both preserve composition. But they're different mappings.

The question is: how do F and G relate to each other? Is there a systematic relationship between them?

What a Natural Transformation Is

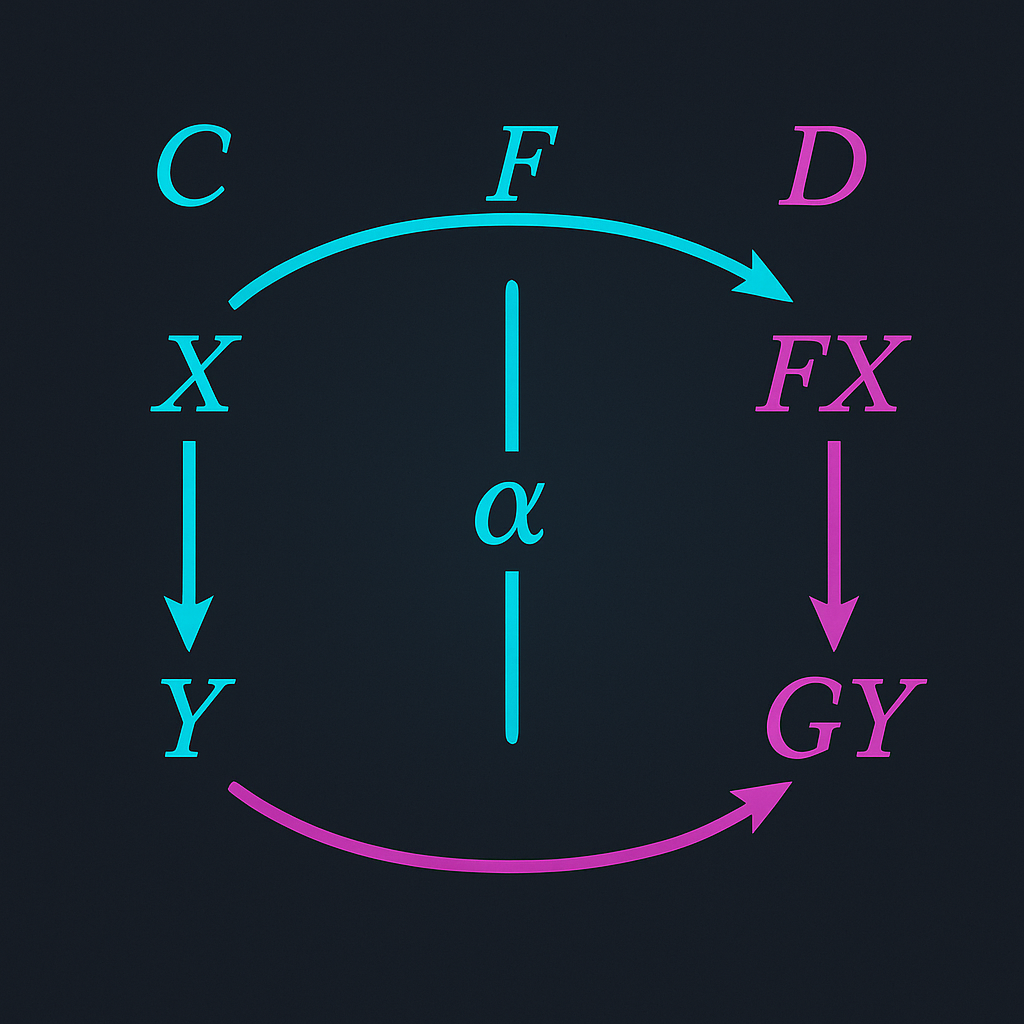

A natural transformation η: F ⇒ G is a way of systematically relating two functors.

For every object A in C, the natural transformation provides an arrow η_A: F(A) → G(A) in D. This arrow connects what F does to A with what G does to A. It's a component of the transformation—one piece of the systematic relationship.

But the components must fit together. They must satisfy the naturality condition:

For every arrow f: A → B in C, the following diagram commutes:

F(A) --F(f)--> F(B)

| |

η_A η_B

| |

v v

G(A) --G(f)--> G(B)

Commuting means: going across the top (F(f)) and then down (η_B) gives the same result as going down (η_A) and then across the bottom (G(f)).

η_B ��� F(f) = G(f) ∘ η_A

In words: if you transform an object using F, then move within F's image, then transform to G's image, you get the same result as if you first transform to G's image, then move within G's image.

The relationship between the functors is consistent with the structure they're preserving. The transformation respects the arrows.

What This Means Intuitively

Natural transformations say: different paths, same structural effect.

F is one way of translating from C to D. G is another way. The natural transformation η relates them by showing how F's translations can be systematically converted to G's translations, in a way that respects the structure both are preserving.

Think of it as equivalence-with-structure.

F and G aren't identical—they make different choices. But they're naturally equivalent—there's a systematic, structure-respecting way to go from one to the other.

The naturality condition is crucial. It's not enough to have arbitrary arrows from F(A) to G(A). The arrows have to fit together. They have to respect the web of relationships in both categories. The transformation must be coherent across the entire structure.

This is why natural transformations matter: they capture when two different approaches are genuinely equivalent in a deep, structural sense, not just superficially similar.

Back to Therapy

Apply this to the therapeutic example.

Let the source category C be the category of psychological problems—configurations of distress, dysfunction, suffering. Objects are problem-states; arrows are the natural transitions between problem-states (how problems evolve, worsen, or occasionally spontaneously resolve).

Let the target category D be the category of psychological wellness—configurations of function, flourishing, capacity. Objects are wellness-states; arrows are transitions within wellness.

A therapeutic modality is a functor from C to D. It takes problem-states and maps them to the wellness-states they can reach through that therapy. It takes the natural dynamics of problems and maps them to the dynamics of recovery.

CBT is one functor, call it F_CBT. It maps problem-states to wellness-states via cognitive restructuring and behavioral change.

Psychodynamic therapy is another functor, G_psychodynamic. It maps problem-states to wellness-states via insight, transference, and working-through.

These functors make different choices. The wellness-state that CBT reaches from a given problem-state might differ from the wellness-state that psychodynamic therapy reaches. The path through recovery is different. The experience is different.

But suppose there's a natural transformation between them.

The transformation would provide, for each problem-state A, a connection between F_CBT(A) and G_psychodynamic(A). It would show how the CBT outcome relates to the psychodynamic outcome. And it would do this systematically—respecting the structure of how problems evolve and how recovery proceeds.

What would this mean?

It would mean that while the therapies take different paths, the structural relationship between their outcomes is consistent. They're accomplishing equivalent structural work through different routes. The difference is real—different experiences, different mechanisms, different vocabularies—but the equivalence is also real. They're naturally transformable into each other.

This explains how different therapies can "work" in some common sense while being genuinely different. They're different functors with a natural transformation between them. Different but systematically related. Not identical, not arbitrary, but naturally equivalent.

Isomorphism and Weaker Equivalences

When the natural transformation has an inverse—when there's another natural transformation going the other direction, and they compose to identities—the functors are naturally isomorphic. This is the strongest equivalence: F and G are, for structural purposes, the same functor.

Natural isomorphism is rare. More often, natural transformations go in one direction but not the other. Or they go both directions but don't compose to identities. The functors are related but not identical.

This gradation matters. Some therapeutic modalities might be naturally isomorphic—truly equivalent, interchangeable for structural purposes. Others might be naturally related without being equivalent—one might be a refinement of the other, or they might partially overlap.

The precision of the categorical language helps. Instead of vague claims that therapies are "similar" or "different," we can ask: what's the natural transformation? Is it an isomorphism? What structure does it preserve or lose?

The answer might be: CBT and psychodynamic therapy are naturally related through a transformation that preserves symptomatic improvement but doesn't preserve subjective experience of the healing process. They achieve structurally similar outcomes through experientially different paths. The natural transformation connects them without collapsing them.

Why Naturality Matters

The naturality condition—that the components fit together, that the diagram commutes—isn't just technical requirement. It captures something important about genuine equivalence.

Without naturality, you have mere correlation. You could pick arbitrary arrows from F(A) to G(A) for each object A. Sometimes F's outcome and G's outcome happen to connect. But the connections are ad hoc, coincidental, unexplained.

With naturality, you have systematic equivalence. The connections respect the structure. They fit together across the whole category. They explain why the different paths lead to related places.

Naturality distinguishes genuine theoretical equivalence from mere empirical correlation. Two therapies might happen to produce similar outcomes in a study without being naturally equivalent—the similarity might be coincidental, unstable, non-systematic. Or they might be naturally equivalent—the similarity grounded in structural relationship that holds across contexts.

The naturality condition is what makes equivalence deep rather than shallow. It's what makes "different paths, same place" a structural truth rather than an accident.

Natural Transformations in Other Domains

The pattern extends beyond therapy.

Different formalizations of a theory. In science, the same phenomenon can often be formalized in different ways. Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics are different formalizations of classical physics. Schrödinger's wave mechanics and Heisenberg's matrix mechanics are different formalizations of quantum mechanics. In each case, the formalizations are related by natural transformations—systematic equivalences that show they're accomplishing the same structural work through different mathematical routes.

Different educational approaches. Teaching the same content through different methods—lecture versus discussion, visual versus verbal, structured versus exploratory. When these work, it's because they're naturally equivalent: different functors from "content to be learned" to "understanding in the learner," related by transformations that preserve learning outcomes while varying learning experience.

Different organizational structures. Hierarchy and flatness, centralized and distributed, can sometimes accomplish similar coordination. When they do, they're naturally related—different functors from "coordination problem" to "coordinated action," connected by transformations that preserve coordination while varying structure.

Different relationship styles. Two couples might have very different dynamics—different communication patterns, different divisions of labor, different ways of being together—yet be equally healthy, equally functional. They're different functors from "individual needs" to "mutual flourishing," related by natural transformations that preserve flourishing through different relational routes.

In each case, the natural transformation explains how genuine difference coexists with genuine equivalence. The paths differ; the structural destination relates.

When Natural Transformations Don't Exist

Not all functors are naturally related. Sometimes F and G are just different, with no systematic connection.

This is important. The existence of natural transformations is not guaranteed. It's a substantive fact about the structure of the domains involved.

When natural transformations don't exist between approaches, the approaches are genuinely incommensurable. They're not doing equivalent work; they're doing different work. The outcomes don't systematically relate; they're just different outcomes.

This happens. Some therapeutic modalities might genuinely treat different things, achieve different outcomes, address different aspects of the problem. No natural transformation relates them because they're not naturally related. They're functors to different destinations, not different paths to the same place.

Recognizing when natural transformations don't exist is as important as recognizing when they do. It prevents the false equivalence of treating genuinely different approaches as variations on a theme. It preserves the reality of incommensurability where incommensurability exists.

The question "is there a natural transformation?" is an empirical question, not a definitional one. It depends on the actual structure of the domains, the actual relationships between approaches. The mathematics gives us the question to ask; reality gives us the answer.

Composing Natural Transformations

Natural transformations compose.

If η: F ⇒ G and θ: G ⇒ H, then there's a composite transformation θη: F ⇒ H. You can chain the relationships.

And functors and natural transformations together form a rich structure. There are categories of functors, where the arrows are natural transformations. There are higher categories where natural transformations are objects and there are arrows between them.

This might seem like abstraction spiraling into irrelevance. But it captures something real.

Chains of equivalence. If psychodynamic therapy is naturally equivalent to EMDR, and EMDR is naturally equivalent to somatic experiencing, then psychodynamic and somatic are naturally equivalent through the composite transformation. The chain of relationships preserves structure through the entire sequence.

Equivalence of equivalences. Sometimes there are multiple natural transformations between the same functors—multiple ways of connecting F and G. The relationships between these relationships might themselves be systematic. Higher categorical structure captures this.

The web of connections. Reality isn't just objects and arrows. It's objects, arrows, arrows between arrows, and potentially further levels. Natural transformations reveal that the world has more structure than objects and mappings—it has structure in how mappings relate.

For meaning, this matters. The coherence operator we discussed doesn't just integrate properties at one level. It integrates across the web of functors and transformations that connect levels. Meaning propagates not just through functors but through the transformations between functors—through the relationships between different ways of relating scales.

What Natural Transformations Tell Us About Meaning

If meaning is coherence under constraint, and coherence propagates through functors, then natural transformations tell us something important: meaning has multiple valid expressions.

The same meaning can be carried by different functors. Neural coherence and psychological coherence are related by functor, but there might be multiple valid functors—multiple ways of mapping neural to psychological. Natural transformations between these functors reveal the different-but-equivalent ways meaning can manifest.

Equivalence is structural, not superficial. When we say two things "mean the same," naturality tells us what we should mean by that. Not that they're identical. Not that they're arbitrarily similar. But that they're systematically related in a way that respects the structure of meaning itself.

Different paths are genuinely different. Natural transformation doesn't collapse F into G. Both remain distinct. The transformation relates them without identifying them. The paths matter, even when they're equivalent. How you get somewhere is part of what it means to be there.

The space of equivalences matters. Sometimes there's one natural transformation between F and G; sometimes there are many; sometimes there are none. The structure of this space—what equivalences exist and how they relate—is part of the structure of meaning. Meaning lives not just in the functors but in the web of their natural transformations.

This is why the same insight can arrive through different modalities—therapy or meditation or relationship or crisis—and feel like the same insight while being different experiences. The insight is the structure that natural transformations preserve. The difference is everything else.

Different paths. Same structural place. Related naturally.

Comments ()