Neuralink: Elon Musk's Bet on the Brain

On January 28, 2024, Elon Musk tweeted: "The first human received an implant from Neuralink yesterday and is recovering well."

That's it. That's how we found out that the most ambitious brain-computer interface project in history had put a chip in someone's head. A tweet.

The patient was Noland Arbaugh, a 29-year-old who'd been quadriplegic since a diving accident eight years earlier. Within weeks, he was streaming on X, playing chess, beating friends at Mario Kart, and controlling everything—the cursor, the moves, the whole interface—using nothing but his thoughts.

Holy shit.

Let's talk about what Neuralink actually built, what it's actually doing, and why it might matter even if you think Elon Musk is a lunatic.

The Hardware

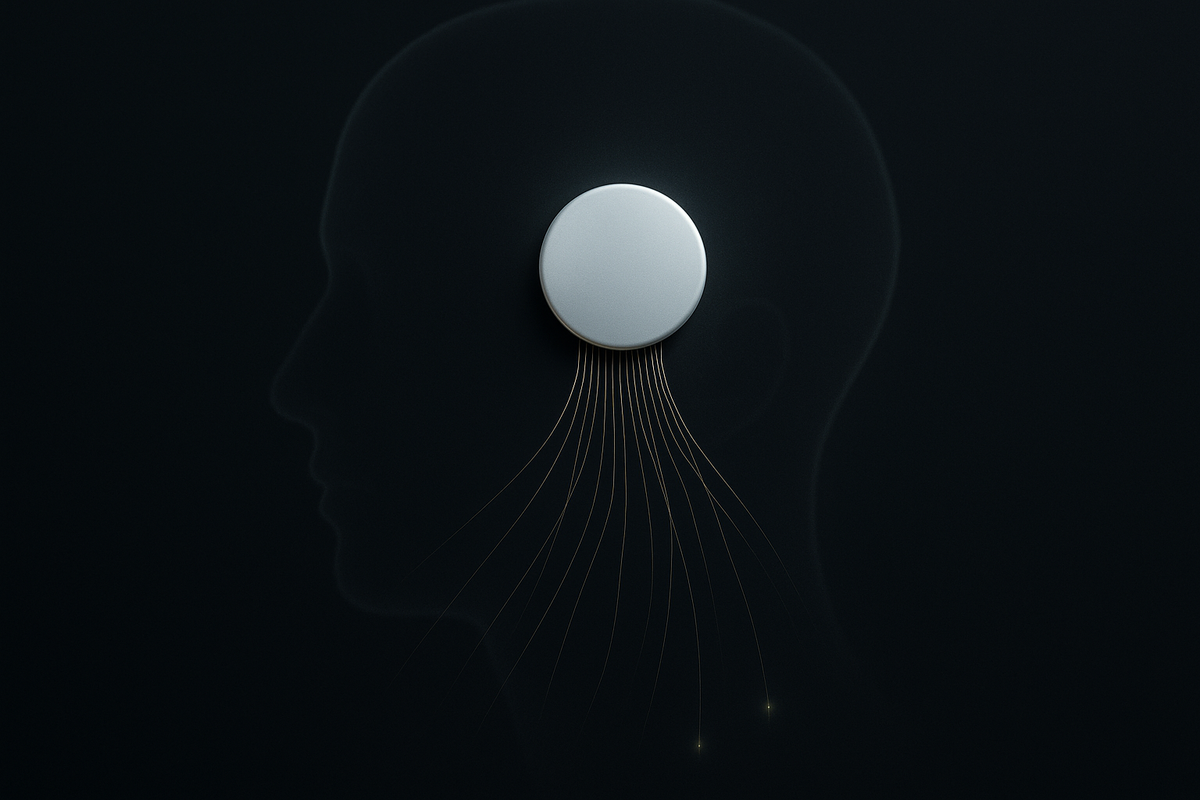

The device implanted in Noland's brain is called the N1. It's about the size of a quarter, roughly 23mm in diameter, and it sits flush with the skull—you can't see it from outside. The surgery creates a small hole in the skull, the device is placed, and the skin is closed over it.

Here's what makes it different from previous BCIs:

1,024 electrodes. The standard Utah array used in academic research has 96 electrodes. Neuralink crammed more than ten times that into a single device. More electrodes means more neurons sampled, which means more information decoded.

Thread architecture. Instead of rigid silicon needles, Neuralink's electrodes sit on incredibly thin, flexible polymer threads—about 5 microns thick, roughly 1/20th the width of a human hair. The theory is that flexible threads cause less damage and trigger less scarring than rigid electrodes, potentially lasting longer in the brain.

Custom surgical robot. You can't sew those threads by hand—they're too thin. Neuralink built a robot specifically to insert them. The robot uses computer vision to identify blood vessels on the brain surface and avoid them while placing threads at precise depths.

Wireless everything. No wires poking through the skull. The implant processes signals onboard, compresses the data, and transmits it wirelessly to an external receiver. The patient charges it inductively, like a smartphone.

The full stack. Neuralink doesn't just make the implant. They designed the surgical robot, the electrodes, the chip, the wireless transmission, the signal processing algorithms, and the user interface. It's Apple-style vertical integration for brain-computer interfaces.

This is genuinely impressive engineering. Whatever you think of Musk, the technical team at Neuralink has built something that advances the state of the art.

What Noland Can Actually Do

Let me be specific, because the headlines often aren't.

Noland can control a computer cursor using his thoughts. He positions the cursor and clicks by imagining specific movements. After training, this becomes intuitive—he's not consciously thinking "move cursor left," he's just... moving the cursor left. The same way you don't consciously think about moving your physical hand.

With cursor control, he can:

- Browse the web - Play video games (chess, Mario Kart, Civilization VI) - Control streaming software to broadcast himself playing - Navigate computer interfaces generally

He's described it as "using the Force." Think about moving, and the cursor moves.

What he cannot do (yet):

- Move his actual limbs. The Neuralink reads signals; it doesn't stimulate his spinal cord or muscles. - Feel anything through the interface. It's one-way—brain to computer, not computer to brain. - Control anything outside the designated computer interface. There's no robot arm, no smart home integration (yet). - Type at the speed of a keyboard. He's using point-and-click, not direct neural typing.

This is important to keep clear. Neuralink's first patient is controlling a computer cursor. That's the actual capability. It's revolutionary for people who can't move—and it's just the beginning of what the technology might do—but it's not telepathy, not mind uploading, not superhuman cognition.

The reality is remarkable enough. It doesn't need hype.

The Second Patient and the First Problem

A second Neuralink patient, identified only as "Alex," received an implant in August 2024. He's also quadriplegic and has reported similar experiences—intuitive cursor control, gaming, computer use.

But there's been a complication.

In Noland's case, some of the electrode threads retracted from the brain tissue after implantation. Neuralink disclosed this in a blog post a few months after the surgery. The threads that were supposed to be embedded in the motor cortex partially pulled back, reducing the number of electrodes in contact with neurons.

This decreased the amount of signal the device could capture. Neuralink compensated by adjusting their algorithms—they modified the decoding software to work with the reduced electrode count and changed sensitivity settings. Performance recovered, and Noland has continued using the system effectively.

But this is a significant issue. The whole point of the flexible thread design was durability—the theory that flexible electrodes would stay in place better than rigid ones. If threads are retracting, that theory needs revision.

It's possible this was a one-time problem related to this specific surgery. It's possible it indicates a more fundamental design issue. We don't have enough data yet. Two patients isn't a clinical trial.

This is what experimental technology looks like. Problems arise. You solve them or you don't.

The Musk Factor

It's impossible to talk about Neuralink without talking about Elon Musk. And that's a problem, because it makes it hard to evaluate the technology on its merits.

Musk has made wildly optimistic claims about Neuralink for years. In 2019, he said they hoped to begin human trials by 2020 (they started in 2024). He's talked about treating blindness, paralysis, obesity, depression, autism, schizophrenia—conditions that are nowhere near being addressed by current BCI technology. He's mentioned "digital telepathy" and "symbiosis with AI" as future applications.

These claims range from plausible-but-far-off to fantasy. Treating paralysis with motor BCIs is a real goal, actively being researched by multiple groups. Treating autism with a brain implant is not a thing—autism isn't even a well-defined neural disorder that you could target with electrodes.

Musk also has a pattern of overpromising timelines and underdelivering. SpaceX has been more successful than critics expected, but it's also years behind many of Musk's stated schedules. Tesla's "Full Self-Driving" has been perpetually imminent for a decade. The Hyperloop is vaporware.

So there's reason for skepticism when Musk makes claims about Neuralink.

But here's the thing: the actual engineering team at Neuralink includes serious neuroscientists and engineers. Many came from academic BCI research. They're doing real work, publishing real data, and putting real devices in real patients.

The question isn't whether Musk is trustworthy. It's whether the technology works. And so far, it appears to.

The Competition

Neuralink isn't alone. Let's see how it compares.

Synchron has a completely different approach: the stentrode. Instead of drilling into the skull, they insert a device through a blood vessel—similar to how cardiologists insert stents. The stentrode lodges inside a blood vessel near the motor cortex and records through the vessel wall.

Synchron's device has fewer electrodes (16 versus 1,024) and lower resolution. But the procedure is minimally invasive—no craniotomy, no open brain surgery. They've implanted multiple patients in Australia and the US, and their patients are controlling computers, sending emails, and browsing the web.

For many patients, Synchron's approach might be preferable. Lower resolution but much lower surgical risk. The tradeoff depends on the application.

Blackrock Neurotech has been making Utah arrays for decades. These are the electrodes used in almost all the landmark academic studies—Jan Scheuermann's robotic arm, the Stanford speech decoding work, most of the research we've discussed. They're proven technology with years of human data.

Blackrock is now developing higher-density arrays and working on bidirectional systems. They have the track record and the regulatory history. They're not as flashy as Neuralink, but they're not playing catch-up either.

Precision Neuroscience was founded by Benjamin Rapoport, a Neuralink co-founder who left to pursue a different approach. Their "Layer 7" device sits on the brain surface rather than penetrating it. This offers higher resolution than Synchron but lower invasiveness than Neuralink.

BrainGate isn't a company—it's a research consortium spanning Brown University, Stanford, Massachusetts General Hospital, and other institutions. They've been doing this longer than anyone and have generated most of the fundamental science. Neuralink is building on their work.

The field is competitive and rapidly evolving. Neuralink's advantages are scale (more electrodes), integration (the full stack), and resources (Musk's money and manufacturing capacity). Their disadvantages are timeline (they started human trials later than competitors) and hype (claims that outrun evidence).

This is a real race with multiple legitimate contenders.

What Comes Next

Neuralink's FDA-approved trial, called PRIME (Precise Robotically Implanted Brain-Computer Interface), is designed to assess safety and initial efficacy. They're implanting paralyzed patients and measuring their ability to control computers.

The next phase, presumably, would be larger trials with more patients and longer follow-up. How long do the electrodes last? Does performance degrade over time? What's the complication rate across many surgeries?

Then: expanded applications. Neuralink has mentioned wanting to address blindness (a visual prosthesis that would require a completely different implant in the visual cortex) and spinal cord injury (potentially stimulating below the injury to restore movement, not just reading from above it).

Further out, Musk has talked about cognitive enhancement for healthy people. This is the science fiction scenario—brain chips that make you smarter, let you communicate telepathically, merge you with AI.

Let's be real about what this would require:

To genuinely enhance cognition, you'd need to interface with cognitive processes that we don't yet understand. We can decode motor intentions because we understand motor cortex well. We don't understand how abstract thought, creativity, or general intelligence are represented in neural activity. You can't interface with what you can't decode.

To enable telepathy, you'd need to encode and decode the full complexity of human thought—not just motor commands but concepts, emotions, memories. We're nowhere close to that.

To "merge with AI," you'd need... well, it's not even clear what that would mean. AI systems process information differently than brains. "Merging" them isn't a well-defined engineering problem.

The near-term applications are real. The far-term speculation is speculation.

The Stakes

Here's why Neuralink matters even if you never plan to get a brain chip.

First: it's accelerating the field. Neuralink's resources, engineering talent, and manufacturing capacity are pushing BCI technology forward faster than academic labs could manage alone. Competition drives innovation. Even if you think Musk is problematic, the engineers at Neuralink are doing work that benefits everyone.

Second: it's normalizing the concept. Ten years ago, brain-computer interfaces were a niche academic topic. Now millions of people have watched Noland play chess with his mind. Public awareness changes what's possible—it influences funding, regulation, and talent flow.

Third: the underlying technologies have applications beyond BCIs. High-density electrodes, flexible electronics, wireless neural recording, surgical robotics—these have implications for neuroscience research, epilepsy treatment, and other areas.

Fourth: this is the beginning. The first computers filled rooms and calculated ballistics tables. The first brain-computer interfaces control cursors. What they become depends on what we learn from these early experiments.

Noland Arbaugh, right now, is playing video games with his mind. That's not the destination. That's the proof of concept.

The question isn't whether neural interfaces work. They do. The question is how far they can go—and who decides.

What to Watch

Let's be honest about timelines and what matters.

Now through 2028: Early trials with small patient populations. The focus is safety, durability, and basic efficacy. Can the threads stay in place? Do signals degrade? What's the complication rate?

2028-2035: If trials succeed, FDA approval for specific indications. BCIs become a treatment option—expensive, requiring surgery, but available.

Beyond 2035: Speculative. More applications, possibly cognitive enhancement. Depends entirely on what the earlier data shows.

The pattern with transformative technologies: longer than hype suggests, faster than skeptics predict. Anyone who tells you exactly how this plays out is selling something.

What matters: Electrode durability (the thread retraction is a warning sign). Complication rates (two patients isn't enough data). Performance metrics over time. Regulatory decisions. What competitors are doing.

The spectacle is entertaining. The substance is in the data. Watch the data.

The Bet

Here's what Neuralink is really betting on: that brain-computer interfaces will become as transformative as computers themselves.

Today we have keyboards and mice, voice assistants and touchscreens. These are all translation layers between human intention and machine action. Your brain has an intention, you translate it into a physical movement, the movement activates an interface, the interface triggers computation.

Neuralink is betting that direct neural interfaces will eventually bypass all those translation layers. Brain to computer, no intermediary. And if that works—if BCIs become fast, reliable, and high-bandwidth—then everything we do with computers changes.

It's a big bet. Maybe too big. The brain is more complex than any system we've engineered. Our understanding of neural coding is still primitive. The gap between controlling a cursor and "merging with AI" is vast.

But the first bet has already paid off. There's a man in Texas playing chess with his mind. That's not speculation. That's happening right now.

The rest of the bet is still open.

The future of brain-computer interfaces isn't written. It's being debugged, one patient at a time.

Comments ()