Every Neuroscience Headline Lies: Here's What We Actually Know

"Scientists discover the brain region for love."

"This is your brain on meditation—and it's incredible."

"Neuroscience proves free will is an illusion."

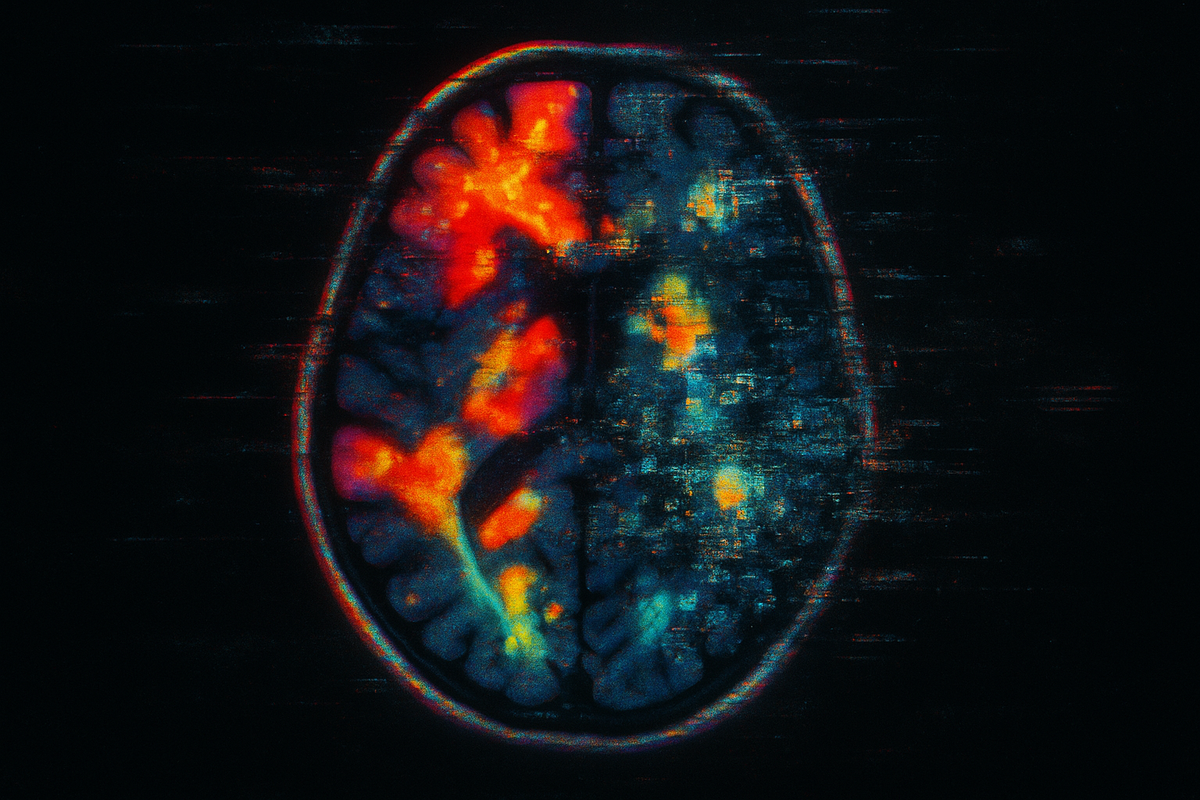

You've seen these headlines. They show up every week, accompanied by colorful brain scans with blobs lighting up in red and yellow. They make neuroscience sound like it's cracked the code, like we've mapped the mind the way we mapped the genome.

It's mostly bullshit.

Not because neuroscience isn't making progress—it is, dramatically. But because the gap between what studies actually show and what headlines claim is vast. A paper showing slightly elevated activity in one region during one task, in 23 undergraduates, becomes "Scientists Find the Brain Region for X." The statistics are often underpowered. The effects are often tiny. The interpretations are often wild extrapolations.

And yet: there are things neuroscience has actually established. Real findings. Replicated results. Solid ground.

This article is about what we actually know—the signal underneath the noise.

The Replication Problem (Why You Should Be Skeptical)

Let's start with why skepticism is warranted.

In 2015, a team of researchers tried to replicate 100 psychology studies, many of them neuroscience-adjacent. Only 36% replicated. The effect sizes of those that did replicate were, on average, half as large as originally reported.

Neuroscience has similar problems. A 2020 analysis found that most fMRI studies are statistically underpowered—they don't have enough participants to reliably detect the effects they're looking for. The median sample size in cognitive neuroscience studies is around 25 participants. To detect a medium-sized effect with 80% power, you need around 80.

This matters because small samples combined with noisy data and flexible analysis methods create a recipe for false positives. Researchers can analyze the data multiple ways, compare multiple brain regions, and report only the comparisons that hit statistical significance. This isn't fraud—it's just how incentives work when journals want surprising results and careers depend on publications.

The result: a literature full of findings that don't replicate, brain regions that "light up" for everything, and bold claims built on shaky foundations.

Does that mean neuroscience is worthless? No. It means you need to know what's been replicated and what hasn't.

What We Actually Know: The Solid Ground

Here's the stuff that's held up. The findings that replicate. The claims you can actually believe.

1. Localization Is Real (But Not How You Think)

Different brain regions do specialize in different functions. This isn't phrenology—it's been confirmed by over a century of lesion studies, split-brain research, and modern imaging.

Broca's area (left frontal lobe) is involved in speech production. Damage it, and people can understand language but struggle to produce it. Wernicke's area (left temporal lobe) is involved in language comprehension. Damage it, and people speak fluently but nonsensically.

The hippocampus is critical for forming new memories. Patient H.M. had his hippocampi removed to treat epilepsy; he could no longer form new long-term memories for the rest of his life. This has been replicated countless times in other patients and animal models.

The amygdala is involved in processing emotional salience, especially fear and threat. Patient S.M., born with a rare genetic condition that destroyed her amygdalae, cannot experience fear in the normal way.

The cerebellum, long thought to just handle motor coordination, also contributes to timing, prediction, and procedural learning. Damage it, and you don't just stumble—you also have trouble with precise timing of speech and movement sequences.

But here's the caveat: localization doesn't mean each region does one thing exclusively. The brain is massively interconnected. Every "area" participates in multiple functions. Every function involves multiple areas. The popular idea of "left brain vs. right brain" is oversimplified to the point of being misleading.

Localization is real. Simple localization stories are mostly wrong.

2. Plasticity Is Profound

The adult brain changes. This was controversial fifty years ago; it's now established fact.

London taxi drivers, who spend years memorizing the city's street layout, have measurably larger posterior hippocampi than control subjects. And when they retire, that region shrinks. The brain literally reshapes itself around what you practice.

Stroke recovery demonstrates plasticity in action. When a brain region is damaged, neighboring regions can sometimes take over its functions—not perfectly, but enough to recover significant capability. The younger the patient, the more dramatic the plasticity.

Learning changes brain structure. Juggling training increases gray matter in visual and motor areas. Musical training changes auditory cortex organization. Second language acquisition changes the size and connectivity of language regions.

The brain isn't fixed after childhood. It's constantly remodeling itself based on experience. The phrase "neurons that fire together wire together" (Hebb's rule) is a simplification, but the core insight is solid: repeated patterns of activity strengthen the connections that produce them.

3. The Brain Is Massively Parallel

Your brain runs on 20 watts. The most powerful supercomputers use megawatts. How does biology achieve such efficiency?

Parallelism. Your brain doesn't process information sequentially like a computer executing instructions one at a time. It processes in parallel across billions of neurons simultaneously.

Visual processing illustrates this. When you look at a scene, different features—color, motion, edges, faces—are processed in different regions simultaneously. There's no central processor assembling the image; the processing is the assembly.

Memory retrieval is similarly distributed. A memory isn't stored in one location; it's a pattern of activation across many regions. The hippocampus helps coordinate retrieval, but the content is distributed throughout cortex.

This architecture is radically different from digital computers. It's why the brain is so good at pattern recognition, so fault-tolerant (you can lose neurons without losing functions), and so energy-efficient. It's also why building artificial neural networks—crude approximations of biological ones—has revolutionized AI.

4. Prediction, Not Just Reaction

For decades, neuroscience treated the brain as a stimulus-response machine. Signals come in, processing happens, actions come out.

The new view: the brain is fundamentally a prediction machine.

Your brain doesn't wait for sensory data to arrive and then process it. It constantly generates predictions about what's coming and compares those predictions to actual input. Perception is less like a camera and more like a hypothesis-testing engine.

This framework—called predictive processing or predictive coding—explains a huge range of phenomena:

- Illusions occur when predictions override actual sensory data - Attention is the process of increasing precision on certain predictions - Learning is updating predictions that turned out wrong - Surprise is what happens when predictions fail dramatically

Karl Friston, the neuroscientist who formalized much of this theory, argues that minimizing prediction error is the brain's fundamental operating principle. It's controversial, but the basic insight—that brains predict rather than just react—is now mainstream.

5. Networks Matter More Than Regions

The early days of brain imaging focused on finding "the" region for each function. The new neuroscience focuses on networks—distributed systems of regions that work together.

The default mode network (DMN) activates when you're not focused on the external world—during mind-wandering, self-reflection, imagining the future, remembering the past. It's the brain's "screensaver mode," but it's doing real work: maintaining your sense of continuous self.

The salience network detects important events and switches attention between external focus and internal processing. It's the traffic cop, deciding what deserves attention.

The frontoparietal control network handles executive functions—planning, decision-making, cognitive control. It's the most flexible network, reconfiguring itself depending on task demands.

These networks interact dynamically. Mental illness often involves dysfunctional network connectivity—too much communication here, too little there. The network perspective has transformed how we understand disorders like depression, schizophrenia, and autism.

Single regions don't cause complex behaviors. Network dynamics do.

What We Don't Know (The Honest Gaps)

For all the progress, there's plenty neuroscience hasn't figured out.

How do neurons produce consciousness? We know consciousness correlates with certain kinds of brain activity. We have no idea how neural activity becomes subjective experience. This is the "hard problem," and it's still completely open.

How is information encoded? We know information is somehow stored in patterns of synaptic strength, but we can't read it out. We can't look at a brain and extract the memories stored there. The code is unknown.

How do decisions actually happen? We can see brain activity preceding decisions, but we don't understand how competing options are evaluated and one is selected. The neural basis of choice remains murky.

Why do brains sleep? We know sleep is critical—deprive an animal of sleep and it dies. We have theories about memory consolidation, metabolic waste clearance, synaptic homeostasis. None is definitively proven.

How do 86 billion neurons become a unified experience? The "binding problem"—how distributed processing becomes unified perception—is unsolved. You see a red ball as a single object, but color and shape are processed in different regions. How does it come together?

These aren't minor details. They're central questions that decades of research haven't answered.

The Tools That Changed Everything

Much of what we know comes from new tools that let us see and manipulate the brain in ways that were impossible before.

fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) measures blood flow as a proxy for neural activity. It has good spatial resolution (millimeters) but poor temporal resolution (seconds). It's the source of most colorful brain images—and most hype.

EEG (electroencephalography) measures electrical activity directly, with excellent temporal resolution (milliseconds) but poor spatial resolution. It's been around for nearly a century but remains useful for studying the timing of brain processes.

Optogenetics (which we'll cover in detail) allows precise control of specific neuron types using light. Developed by Karl Deisseroth in the mid-2000s, it transformed neuroscience from correlational to causal: instead of just observing what happens, we can make things happen.

Two-photon microscopy allows imaging of individual neurons in living brains. Combined with genetically encoded activity indicators, it lets researchers watch thousands of individual neurons fire in real time in awake, behaving animals.

Connectomics maps every connection in a brain. We've done this for C. elegans (302 neurons) and a fly (roughly 100,000). Human brains (86 billion neurons, 100 trillion synapses) are orders of magnitude harder, but progress is happening.

Each tool has limitations. The revolution comes from combining them—using optogenetics to establish causation, fMRI to localize, EEG to time, and connectomics to map.

How to Read Neuroscience News

Given all this, how should you interpret the next headline claiming "Scientists Discover X About the Brain"?

Check the sample size. Under 30 participants? Be very skeptical. Under 100? Still be cautious.

Check if it replicated. A single study proves little. Ask: has this been found by multiple labs, multiple times?

Check the effect size. Statistical significance isn't the same as practical importance. A "significant" difference of 1% in brain activation means almost nothing.

Beware reverse inference. Just because a region is active during a task doesn't mean it's necessary for that task. The amygdala activates for lots of things besides fear. Activity doesn't equal causation.

Look for manipulation, not just correlation. The strongest findings come from studies that intervene—lesion studies, stimulation studies, optogenetics—not just observation.

Remember the file drawer. For every published positive finding, many negative findings went unpublished. Publication bias inflates the apparent reliability of effects.

Most neuroscience headlines fail these tests. The findings that pass them are worth taking seriously.

What This Series Will Cover

This is the first article in a series on the new neuroscience—the methods, the findings, and the frameworks that have emerged in the last two decades.

We'll explore connectomics and the quest to map every synapse. Optogenetics and the power to control neurons with light. The glial cells that make up half your brain and might be more important than neurons. Neuroinflammation and the immune system's role in brain disorders. The default mode network and the neuroscience of the self. Predictive processing and the brain as prediction machine.

And we'll end with a synthesis: what all of this tells us about what brains actually do, and what it means for understanding ourselves.

The brain is the most complex object in the known universe. We're finally learning how it works.

Further Reading

- Poldrack, R.A. (2018). The New Mind Readers: What Neuroimaging Can and Cannot Reveal about Our Thoughts. Princeton University Press. - Open Science Collaboration (2015). "Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science." Science. - Yarkoni, T. (2009). "Big Correlations in Little Studies." Perspectives on Psychological Science. - Button, K.S. et al. (2013). "Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience." Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

This is Part 1 of the New Neuroscience series. Next: "Connectomics: Mapping the Brain's Wiring"—the quest to map every connection in the brain, synapse by synapse.

Comments ()