The Number e: The Base That Calculus Prefers

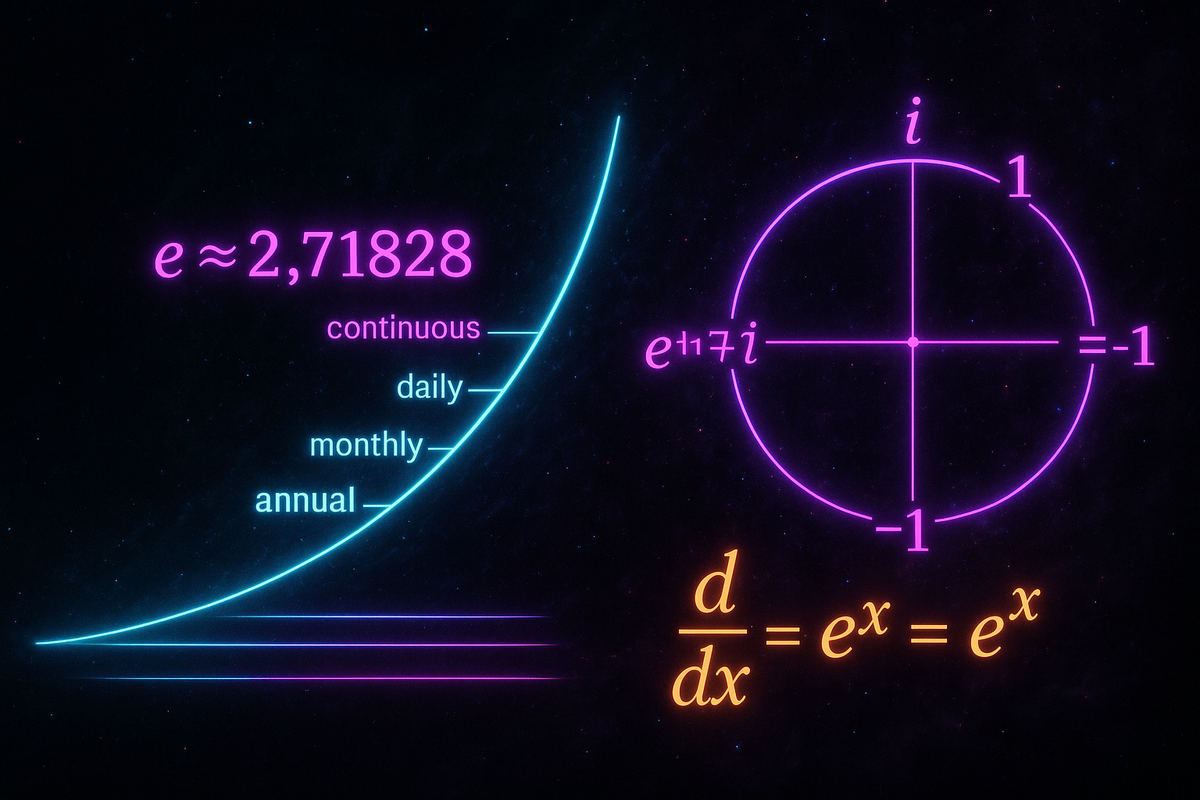

e ≈ 2.71828... is what you get when compound interest compounds forever.

Take $1, earn 100% interest for a year. If it compounds once, you get $2. If it compounds twice (50% each half-year), you get $2.25. Compound more often—monthly, daily, every second—and the amount approaches a limit.

That limit is e dollars.

e isn't constructed by mathematicians to be convenient. It emerges from the nature of continuous growth. It's the number that continuous compounding naturally produces.

Where e Comes From

Start with this limit:

e = lim(n→∞) (1 + 1/n)ⁿ

Try some values:

- n = 1: (1 + 1)¹ = 2

- n = 2: (1 + 1/2)² = 2.25

- n = 10: (1 + 0.1)¹⁰ ≈ 2.594

- n = 100: (1 + 0.01)¹⁰⁰ ≈ 2.705

- n = 1000: (1 + 0.001)¹⁰⁰⁰ ≈ 2.717

- n = ∞: e ≈ 2.71828182845...

The number converges. As compounding becomes continuous, the growth factor approaches e.

Why e Is Special

Many constants are defined by convenience. π is the ratio of circumference to diameter. √2 is the diagonal of a unit square.

e is different. It emerges from the deepest properties of growth and change:

Property 1: The derivative of eˣ is eˣ

d/dx(eˣ) = eˣ

This is unique. No other function equals its own derivative (except trivial multiples). The function eˣ is the fixed point of differentiation.

Property 2: The integral of eˣ is eˣ

∫eˣ dx = eˣ + C

Again unique. eˣ is unchanged by the fundamental operations of calculus.

Property 3: The series for e

e = 1 + 1/1! + 1/2! + 1/3! + 1/4! + ...

= 1 + 1 + 0.5 + 0.167 + 0.042 + 0.008 + ...

This series converges rapidly. Use 10 terms and you get e to 7 decimal places.

e in Compound Interest

The compound interest formula with n compounding periods per year:

A = P(1 + r/n)ⁿᵗ

As n → ∞ (continuous compounding):

A = Pe^(rt)

This is the natural form. Continuous growth at rate r multiplies by e^r per unit time.

Example: $1000 at 5% for 10 years, compounded continuously:

A = 1000 × e^(0.05 × 10) = 1000 × e^0.5 ≈ $1,649

Compare to annual compounding: 1000 × (1.05)¹⁰ ≈ $1,629

Continuous compounding gives slightly more. The difference is the "bonus" from infinitely frequent compounding.

The Natural Logarithm

The natural logarithm (ln) is the logarithm base e:

ln(x) = log_e(x)

ln(e) = 1, ln(1) = 0, ln(eˣ) = x.

Why "natural"? Because:

d/dx(ln x) = 1/x

∫(1/x) dx = ln|x| + C

The simplest antiderivative of 1/x uses base e. Any other base would introduce ugly constants.

e and Differential Equations

The equation for natural growth or decay is:

dy/dt = ky

Solution: y = y₀e^(kt)

This is the fundamental equation of change. Any process where the rate of change is proportional to the current value is exponential with base e.

- Population growth: dP/dt = rP → P = P₀e^(rt)

- Radioactive decay: dN/dt = -λN → N = N₀e^(-λt)

- Cooling: dT/dt = -k(T - Tₐ) → exponential approach to ambient

e isn't chosen for these applications. It arises inevitably.

Euler's Formula

The most famous equation in mathematics:

e^(iπ) + 1 = 0

This connects five fundamental constants: e, i, π, 1, and 0.

More generally, Euler's formula says:

e^(iθ) = cos(θ) + i·sin(θ)

Exponentiation of imaginary numbers produces rotation. The exponential function unifies trigonometry and complex numbers.

Computing e

Method 1: Compound interest limit

(1 + 1/n)ⁿ for large n. Slow convergence.

Method 2: Series

e = ∑(1/n!) for n = 0 to ∞. Fast convergence.

Method 3: Continued fraction

e = 2 + 1/(1 + 1/(2 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(4 + ...)))))

The pattern in the denominators is: 1, 2, 1, 1, 4, 1, 1, 6, 1, 1, 8, ...

e Is Transcendental

Like π, e is:

- Irrational: cannot be expressed as a fraction

- Transcendental: not the root of any polynomial with integer coefficients

This was proven by Hermite in 1873. You cannot construct e with ruler and compass.

The decimal expansion of e never repeats and follows no pattern: 2.71828182845904523536028747135266249775724709369995...

Why Use Base e Instead of Base 10?

Base 10 is natural for humans (10 fingers). But base e is natural for calculus.

d/dx(10ˣ) = 10ˣ × ln(10) ≈ 2.303 × 10ˣ

That extra factor of ln(10) appears because 10 isn't the natural base.

d/dx(eˣ) = eˣ

No extra factors. Clean. This is why mathematicians and scientists prefer e.

For practical calculations, base 10 (or base 2 for computers) is fine. But for theoretical work—differential equations, complex analysis, probability—e is the only sensible choice.

e in Probability

The probability of no events in a Poisson process with rate λ over time t:

P(0 events) = e^(-λt)

The base rate of "nothing happens" is an exponential decay.

The limit of the binomial distribution as n → ∞ and p → 0 with np = λ:

(n choose k) × pᵏ × (1-p)^(n-k) → e^(-λ) × λᵏ/k!

e appears because Poisson processes are the limit of many rare events.

The Bell Curve

The normal distribution has e in its formula:

f(x) = (1/√(2π)) × e^(-x²/2)

The e^(-x²) term creates the characteristic bell shape. Its integral over all x equals √π—another deep connection.

Why e Matters

- It's the natural base for growth. Continuous compounding at rate r multiplies by e^r.

- It simplifies calculus. d/dx(eˣ) = eˣ eliminates constant factors.

- It unifies mathematics. Euler's formula connects exponentials, trigonometry, and complex numbers.

- It appears everywhere. Probability, statistics, physics, engineering—e is inescapable.

- It emerges naturally. e isn't imposed by convention. It arises from the structure of continuous change.

The number e is what continuous growth naturally produces. That's why calculus prefers it.

Part 4 of the Exponential Functions series.

Previous: Exponential Decay: Half-Lives and Cooling Next: Compound Interest: Exponential Growth in Finance

Comments ()