Organoid Intelligence: Wetware as Compute

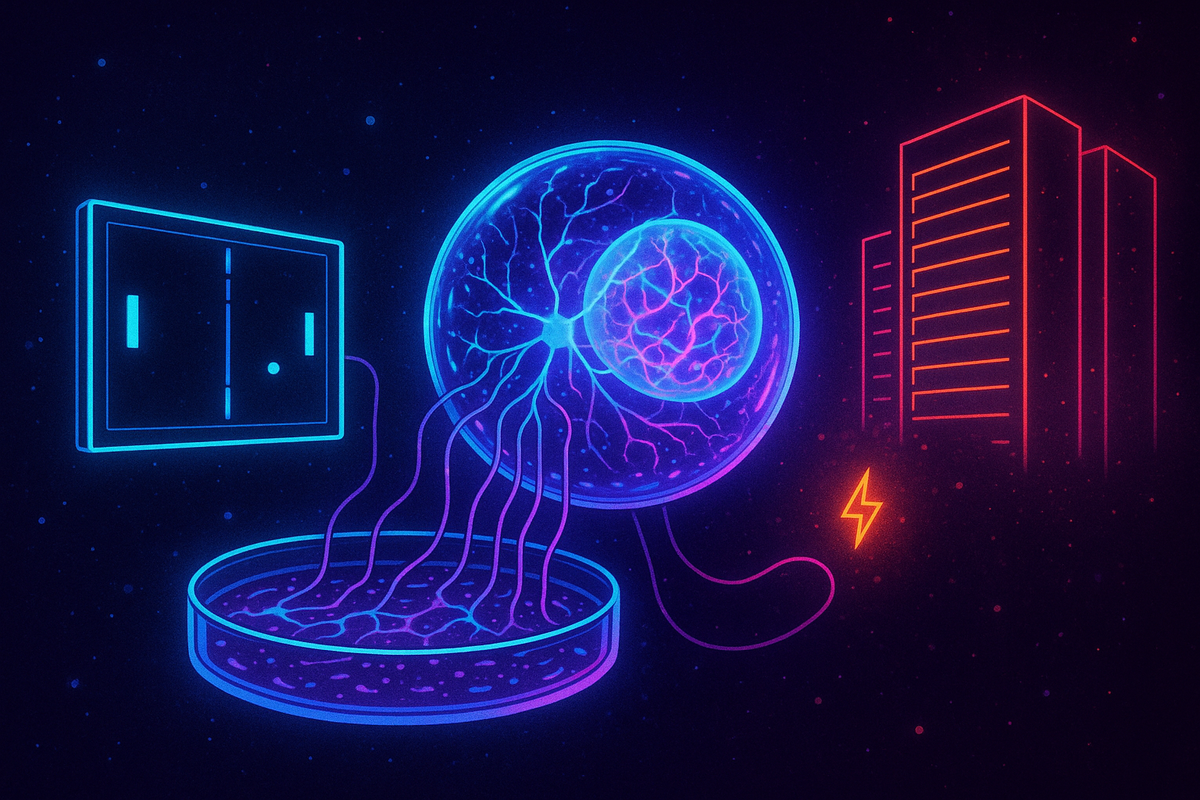

In 2022, a company called Cortical Labs published a paper with an audacious title: "In vitro neurons learn and exhibit sentience when embodied in a simulated game-world."

They had grown a small cluster of human neurons in a dish. They connected it to electrodes. They fed it signals from the classic video game Pong. And the neurons learned to play.

Not well. Not for long. But measurably better than random. The biological tissue learned—adapted its behavior based on feedback—in about five minutes. From scratch. With no prior training.

A clump of neurons in a dish learned Pong faster than any artificial neural network of comparable size.

Welcome to organoid intelligence, where the solution to the compute efficiency problem might be to stop building silicon brains and start growing real ones.

What Is an Organoid?

An organoid is a three-dimensional structure grown from stem cells that mimics the architecture and function of an organ. Scientists have created organoids of kidneys, livers, intestines, and—most relevantly for our purposes—brains.

Brain organoids, sometimes called "mini-brains" (a term neuroscientists hate), are tiny balls of neural tissue, typically a few millimeters across. They don't look like brains. They don't have the complex architecture of actual brains. But they do have real neurons, real synapses, and real neural activity.

The neurons fire. They form connections. They exhibit spontaneous rhythmic activity similar to brain waves. Under the right conditions, they respond to stimuli, adapt their behavior, and—arguably—learn.

This isn't science fiction. Labs around the world are growing brain organoids right now. The technology has existed for about a decade, originally developed for studying brain development and disease. Only recently has anyone thought to use them as computational substrates.

DishBrain: Neurons Playing Pong

Cortical Labs' DishBrain system is the most famous example of organoid computing, but it's worth understanding exactly what they did.

They grew about 800,000 neurons—a mix of human stem cell-derived neurons and mouse neurons—on a multi-electrode array. This is a chip with a grid of electrodes that can both stimulate and record neural activity.

The electrodes delivered signals representing the game state: where the ball was, how fast it was moving, where the paddle was. Other electrodes read out the neural activity, which was interpreted as paddle movement commands.

Crucially, the system provided feedback. When the paddle hit the ball, the neurons received predictable stimulation. When the paddle missed, they received random, chaotic stimulation.

Over about five minutes, the neural activity patterns changed. The paddle started hitting the ball more often. Not perfectly—the dish achieved about 75% accuracy, compared to 50% for random play. But the improvement was real and statistically significant.

The neurons learned that hitting the ball led to predictable states and missing led to chaos. They adapted to maximize predictability. This is exactly what predictive processing theory suggests brains do: minimize prediction error, seek coherent futures.

For comparison: training a comparable artificial neural network to play Pong requires thousands or millions of training iterations and hours or days of compute time. The biological neurons did it in minutes, with no pre-training, using a fraction of the energy.

The implications are staggering. If a few hundred thousand neurons in a dish can learn a basic task in five minutes, what could millions or billions of neurons do?

The Efficiency Argument

Here's why organoid computing matters for the energy crisis in AI: biological neurons are approximately one million times more energy-efficient than silicon transistors for similar computations.

That's not a metaphor. It's a measurement.

Cortical Labs estimates their DishBrain system uses about 10 picojoules per operation—ten trillionths of a joule. Modern GPUs use about 10 nanojoules per operation—ten billionths of a joule. That's a factor of a thousand.

But the comparison is actually worse than that, because "operation" means different things. A neural operation involves complex, high-dimensional integration over thousands of synaptic inputs, followed by a nonlinear threshold decision. A transistor operation is a single bit flip. Comparing them directly understates the biological advantage.

When you account for the computational complexity of each operation, biological neurons are roughly a million times more efficient than silicon for comparable tasks. Some estimates go higher.

This efficiency comes from everything we discussed in the previous article: sparse activation, local processing, analog computation, event-driven signaling. Biological tissue just does it naturally, because that's what neurons evolved to do.

The question is whether we can harness this efficiency for practical computation.

The Case For Wetware

Why grow neurons instead of just copying their principles into silicon? Several reasons:

Evolution did the hard work. Billions of years of optimization produced neurons. Neuromorphic chips try to approximate biological principles, but they're still approximations. Actual biological tissue is the genuine article, optimized by natural selection at every level from molecular machinery to network architecture.

Continuous learning. Biological neural networks learn in real time, all the time. They don't need separate training and inference phases. They adapt to new situations without catastrophic forgetting of old ones. This is something artificial neural networks still struggle with.

Low-precision tolerance. Biological systems work despite enormous molecular noise. They're robust to component failure, temperature variation, and imperfect signals. This tolerance is built in at every level. Silicon systems require elaborate error correction to achieve the same reliability.

Self-repair. Within limits, biological tissue can heal itself. Damaged neurons can sometimes regenerate connections. Dead cells can be replaced. Silicon that breaks stays broken.

Manufacturing efficiency. Growing neurons is, in principle, cheap. You start with stem cells and a culture medium. The neurons build themselves through programmed development. No lithography, no clean rooms, no rare earth elements. The main ingredients are glucose and oxygen.

The biological path to efficient computation isn't about mimicking neurons in silicon. It's about using actual neurons—the real thing, grown in the lab, harnessed for computation.

The Case Against Wetware

This all sounds almost too good to be true. What's the catch?

Speed. Neurons are slow. They fire at most a few hundred times per second. Transistors switch billions of times per second. For tasks that require raw sequential speed, silicon wins overwhelmingly. Biological advantages in energy efficiency are partly offset by disadvantages in throughput.

Reliability. Individual neurons are unreliable. They fire stochastically, miss signals, die randomly. Brains work despite this unreliability because they have enormous redundancy and error-tolerant algorithms. Building reliable computational systems from unreliable components is hard.

Interface. Connecting biological tissue to digital systems is an unsolved problem. Current electrode arrays are crude—thousands of electrodes connecting to millions of neurons. We can't read or write neural activity with anything like the precision we have for silicon.

Longevity. Neurons in dishes don't live forever. Current organoids survive weeks to months. For practical computation, you'd need either longer-lived tissue or mechanisms for continuous replacement and knowledge transfer.

Scalability. Growing bigger organoids is hard. Beyond a certain size, the interior cells die because nutrients can't reach them. Vascularization—growing blood vessels into the tissue—is an active area of research but not solved.

Ethics. Growing human brain tissue raises uncomfortable questions. At what point does an organoid become sentient? Does it suffer? Do we have obligations to it? Current organoids are almost certainly too simple for these concerns, but the questions loom as the technology advances.

None of these objections are necessarily fatal. They're engineering challenges, not fundamental impossibilities. But they explain why organoid computing isn't about to replace data centers.

The Current Frontier

Several companies and research groups are pushing organoid computing forward.

Cortical Labs (Melbourne, Australia) continues developing the DishBrain platform. They've demonstrated learning on multiple tasks beyond Pong and are working on scaling to larger networks and longer-duration systems.

FinalSpark (Switzerland) has created a platform they call the Neuroplatform, offering remote access to biological neural networks. Researchers can submit computational tasks to actual living neurons via the internet. It's like cloud computing, but wetware.

Johns Hopkins researchers have proposed "organoid intelligence" as a formal research program, arguing that brain organoids could eventually power AI systems orders of magnitude more efficient than silicon.

Various academic labs are exploring the interface problem—how to communicate with neural tissue at higher bandwidth and precision. Advances in optogenetics, nanotechnology, and bioelectronics could eventually enable dense, reliable neural interfaces.

The technology is real but early. Current organoid computers are proof-of-concept demonstrations, not practical tools. The gap between a Pong-playing dish and a useful computational system is vast.

But so was the gap between the first transistor and a modern GPU. What matters is whether the trajectory is promising. For organoid computing, it seems to be.

The Hybrid Future

The most likely near-term path isn't pure biological computing. It's hybrid systems that combine biological and silicon components, playing to the strengths of each.

Silicon is good at: speed, precision, reliability, digital interfaces, mass production.

Biology is good at: efficiency, learning, pattern recognition, robustness to noise, low power.

A hybrid system might use biological tissue for the computationally expensive parts—the "thinking"—while silicon handles input/output, error correction, and tasks requiring raw speed. The brain already works this way: peripheral nerves and sensory organs do preprocessing before information reaches the energy-expensive cortex.

This is speculative, but the pieces are falling into place. Interface technology is improving. Organoid culture techniques are advancing. The economic pressure from AI energy costs is growing.

If biological computing becomes ten times cheaper than silicon for certain tasks, economics will drive adoption. If it becomes a hundred times cheaper, it will be irresistible. A million times cheaper? Revolutionary.

We might see biological computing emerge first in niches where its advantages are most pronounced: tasks requiring massive parallelism, real-time learning, or ultra-low power. Think always-on environmental monitoring, adaptive sensors, or implantable medical devices. Success in niches could fund development toward broader applications.

The timeline is uncertain but not impossibly long. Cortical Labs is talking about commercial applications within a decade. Academic researchers are more cautious but see no fundamental barriers. The question isn't whether biological computing works—DishBrain proved that. The question is whether the engineering challenges can be solved economically.

The Deeper Question

Organoid computing raises a question that goes beyond engineering: What is computation?

We've assumed computation means silicon, digital logic, deterministic algorithms. But the brain computes, and it does so with none of those things. It's analog, stochastic, biological. And it works.

Maybe "computation" is more general than we thought. Maybe it's any physical process that transforms information according to useful rules. Maybe neurons in a dish processing Pong signals are computing just as much as transistors in a chip, just differently.

If that's true, then the compute ceiling isn't a limit on computation per se. It's a limit on one particular kind of computation—the silicon kind. Other kinds might have entirely different limits.

The universe has been computing for billions of years, in water and carbon instead of silicon and copper. We call it life. Perhaps the future of artificial intelligence isn't artificial at all.

This isn't a prediction that organoid computing will replace silicon. It's a recognition that the design space for computation is larger than we assumed. Silicon is one point in that space. Biology is another. There may be others we haven't discovered yet.

The compute ceiling is forcing exploration of that design space. When one path hits a wall, you look for alternatives. Organoid computing is one of the most radical alternatives being explored—and one of the most promising.

Further Reading

- Kagan, B. J., et al. (2022). "In vitro neurons learn and exhibit sentience when embodied in a simulated game-world." Neuron. - Smirnova, L., et al. (2023). "Organoid intelligence (OI): the new frontier in biocomputing and intelligence-in-a-dish." Frontiers in Science. - Lancaster, M. A., & Knoblich, J. A. (2014). "Organogenesis in a dish: Modeling development and disease using organoid technologies." Science.

This is Part 4 of the Intelligence of Energy series. Next: "Neuromorphic Chips: Silicon Learns from Neurons."

Comments ()