Perspectivism: Every Being Is the Center of Its Own World

Perspectivism: Every Being Is the Center of Its Own World

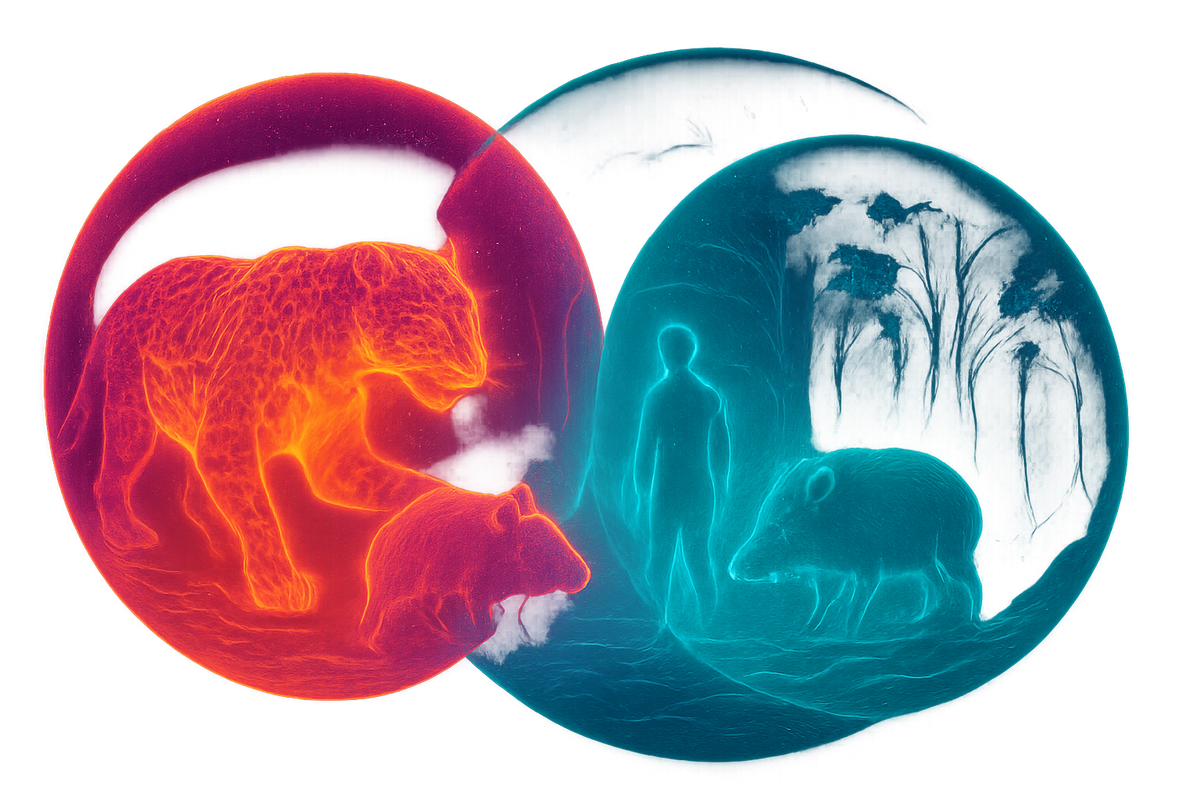

Here's the claim that broke Western anthropology: The jaguar sees itself as human.

Not metaphorically. Not as symbolic expression of kinship or ecological relationship. Actually. From within the jaguar's perspective—experienced through jaguar senses, lived in a jaguar body—it is human, and you are prey.

When it returns to its den, it experiences entering a house. When it drinks blood, it experiences drinking manioc beer. When it encounters a human in the forest, it sees a peccary (a prey animal). This isn't the jaguar being confused. This is what the world looks like from jaguar embodiment.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro calls this Amerindian perspectivism, and it's one of the most sophisticated ontological frameworks anthropology has encountered. It inverts nearly everything about how modern Western thought organizes the relationship between subjects, bodies, and worlds.

Understanding perspectivism requires abandoning the assumption that there's one world we all perceive differently. Instead: there are as many worlds as there are perspectives, and what you perceive depends entirely on the body you inhabit.

Series: Neo-Animism | Part: 3 of 10

The Core Claim: Culture Is Uniform, Nature Is Multiple

Western thought divides the world into nature (objective, universal, governed by physical law) and culture (subjective, variable, socially constructed). One nature, many cultures. We all inhabit the same physical reality, but interpret it through different cultural lenses.

Perspectivism inverts this completely.

In Amazonian ontologies, culture is uniform across species. All beings—humans, jaguars, tapirs, spirits, certain plants—share the same basic social organization, the same cultural logic, the same way of making sense of the world. They all live in villages, have kinship systems, hold ceremonies, drink beer, organize hunts.

What varies is nature—specifically, the body. Different bodies come with different sensory equipment, different motor capacities, different metabolic needs. And the body determines what you perceive.

A jaguar has jaguar eyes (excellent night vision), jaguar teeth (made for tearing flesh), jaguar digestion (carnivorous metabolism), jaguar instincts (predatory drives). These physical capacities shape what appears to the jaguar. Blood appears as manioc beer because that's what nourishment looks like to a carnivore. Humans appear as peccaries because that's what prey looks like to a predator.

The human has human eyes, human teeth, human digestion, human instincts. These shape a different world. Manioc beer appears as manioc beer. Other humans appear as persons. The jaguar appears as dangerous predator.

Same cultural framework, different natures. One culture, many natures. Viveiros de Castro calls this multinaturalism—the inverse of Western multiculturalism.

Bodies as Perspective Engines

The radical move: the body isn't what you have, it's what you are. And what you are determines what you can perceive.

In Western thought, we separate subject (the mind/soul) from body (the physical vehicle). The real "you" is the mental subject residing in a body. Different people have different minds but similar bodies (all human anatomy). We think minds vary, bodies are mostly uniform.

Perspectivism says the opposite. Subjectivity is uniform—all beings are subjects, all have interiority, all experience themselves as "I" at the center of a meaningful world. What varies is physicality—the body-form that generates and constrains perspective.

Your body is a perspective engine. It has sensors (eyes, ears, nose, proprioception) that register certain features of the environment. It has actuators (limbs, vocal cords, digestive system) that enable certain actions. The combination of what you can sense and what you can do determines what appears as meaningful in your perceptual field.

The jaguar's body makes certain things salient: movement in undergrowth (potential prey), territorial markers (other jaguars), the scent of blood (food). The human body makes other things salient: facial expressions (social information), speech patterns (linguistic meaning), tool affordances (technological possibility).

Neither is seeing "reality as it is." Both are bringing forth a world structured by bodily capacities.

This connects directly to contemporary 4E cognitive science: cognition is embodied (shaped by body structure), embedded (coupled to environment), enacted (brought forth through action), extended (distributed across body-world system). The jaguar's cognition and the human's cognition are different enactions of different worlds, using different bodily equipment.

Perspectivism arrived at this insight centuries before cognitive science, through entirely different means: taking seriously the phenomenology of interspecies encounter.

The Shamanic Crossing

If different bodies generate different worlds, an immediate question arises: Can you access another being's perspective?

In Amazonian thought, the answer is: yes, but it's dangerous.

This is what shamans do. Through ritual transformation—drugs, fasting, trance, costume—the shaman temporarily adopts another body, and thereby accesses another perspective. The shaman who dons jaguar skin and drinks ayahuasca can see the world as jaguars see it: blood as beer, humans as peccaries, the forest as village.

But this is risky. If you see too deeply from jaguar perspective, you might become jaguar. The perspective takes over. You forget your human form. You start thinking like a predator, seeing humans as food. This is how humans transform into jaguars in Amazonian cosmology—not magical curse, but perspectival capture.

The danger isn't supernatural. It's ontological. Perspectives have gravity. If you successfully inhabit another body's perceptual framework, you risk losing your grounding in your own. The shaman's skill is crossing perspectives while maintaining the ability to return—staying human while seeing as jaguar.

This has a curious parallel in contemporary psychology: perspective-taking can lead to identity fusion. When you deeply inhabit another's viewpoint, you can lose track of your own boundaries. Empathy carried far enough becomes identification. The shamanic crossing is this dynamic taken to metaphysical conclusion.

The implication: perspectives aren't just viewpoints you can freely swap between. They're coherence configurations. When you adopt one, it reorganizes your entire perceptual field. Shifting perspective means reorganizing coherence—and coherence has inertia. You can cross, but it costs.

What Appears From Different Bodies

Let's map the specific translations. When a jaguar encounters what a human calls "blood," the jaguar experiences manioc beer. Why?

Because manioc beer is what culturally appropriate nourishing drink looks like in Amazonian societies. Humans drink manioc beer at ceremonies. It's social, nourishing, culturally central. The jaguar, participating in the same cultural framework, experiences its appropriate nourishment (blood) as the culturally appropriate drink (manioc beer).

Similarly, when the jaguar looks at a human, it sees a peccary. Why? Because peccaries are what prey looks like to jaguars, and humans are prey from the jaguar's predatory perspective. The human body—slow, soft, poorly defended—registers in the jaguar's perceptual system as game animal.

When the jaguar returns to its den, it experiences a house. Why? Because houses are where persons live in Amazonian culture. The jaguar is a person. Persons live in houses. Therefore the den is experienced as house—with all the attendant meanings (safety, family, territory).

This isn't confusion or error. From within the jaguar's embodied perspective, these are accurate descriptions of reality.

The key insight: there is no view from nowhere. You can't step outside all perspectives to see "what's really there." You're always already embedded in a body, and that body structures what can appear. The jaguar's perspective is as valid as the human's—just different, because different bodies bring forth different worlds.

Modern science tries to access the view from nowhere through instrumentation, mathematics, and third-person description. But even scientific observation happens through embodied researchers using bodily-situated tools. We've built incredibly sophisticated perspective-engines (electron microscopes, particle accelerators, telescopes), but we're still bringing forth a world through particular physical couplings.

Perspectivism makes this explicit: all knowledge is perspectival. The question isn't "what's really real?" but "what appears from which embodied position?"

The Social Implications: Interspecies Diplomacy

If all beings are subjects experiencing themselves as persons, then interspecies encounter becomes diplomatic.

This is how Amazonian peoples actually navigate their environment. When hunters enter the forest, they're not entering neutral territory. They're entering a space filled with other persons—jaguars, tapirs, peccaries, spirits, plant teachers—each occupying their own perspective, each experiencing themselves as human, each pursuing their own concerns.

Hunting isn't harvesting resources. It's negotiating with persons who happen to appear as game from your perspective but experience themselves as persons from their own. Successful hunting requires relationship, respect, sometimes explicit permission. The animal may "offer itself" if the hunter has maintained proper protocols.

This sounds mystical until you recognize it as social ontology taken seriously. If animals are persons, you can't just take. You have to ask. You have to maintain relationship. You have to be someone they would choose to give to.

The practical result: sustainable hunting practices, embedded in social constraint. You don't overhunt, because that would damage your relationships. You don't hunt without proper respect, because the animals—as persons—will respond to disrespect by withdrawing.

Compare this to modern conservation biology's external approach: impose regulations, enforce limits, manage populations. It works, but it treats animals as resources to be managed, not persons to be related to.

Perspectivism embeds constraint in the relationship itself. This isn't more primitive than modern management. It's a different coherence strategy—maintaining ecological balance through social reciprocity rather than external control.

Perspectival Capture and the Problem of Predation

One of perspectivism's most challenging implications: predators see their prey as prey sees itself.

When the jaguar looks at a human, it sees a peccary. But from the peccary's perspective, it sees itself as human (all beings see themselves as human). So when the jaguar hunts, it's hunting something that experiences itself as a person.

This creates an ethical tension: how do you hunt without becoming a murderer?

Amazonian thought resolves this through recognizing that perspectives shift depending on relational position. In the encounter between predator and prey, both are persons, but they appear differently to each other because of their bodily positions and relational dynamics.

The hunter maintains humanity by not identifying too fully with predatory perspective. The risk is that if you become too efficient a hunter, too comfortable with killing, you start seeing humans as prey—you've crossed into predator perspective and might not come back.

This is also why shamanic jaguar transformation is dangerous. If you access jaguar perspective too deeply, you might start seeing your own relatives as food. The perspective doesn't just change what you see—it changes what you want, what matters, what drives action.

The implication: perspectives aren't neutral viewpoints. They're complete packages of perception, motivation, and meaning. Switching perspective means switching coherence configuration—reorganizing your entire way of being in the world.

This has practical application in understanding trauma, addiction, and psychological transformation. When someone says "I'm not myself," they're describing perspectival shift. The world appears different, different things seem valuable, different actions feel necessary. They're experiencing from a different coherence configuration—not their usual one.

Recovery means finding a way back to familiar perspective. Therapy becomes a kind of shamanic guiding: helping someone navigate back from a captured perspective to one that better serves their life.

The Geometry of Perspectivism

How does this translate into coherence geometry?

Perspectives are coherence configurations. Each body-type (human, jaguar, peccary) maintains a particular pattern of coupled dynamics—sensory inputs, motor outputs, metabolic processes, predictive models—that together constitute a stable attractor in phenomenological space.

What you perceive isn't "raw reality" but your system's best guess about what's out there, given your sensory data and prior expectations. This is active inference: your brain (and body) maintains models of the world and adjusts them based on prediction error.

Different bodies have different generative models. The jaguar's predictive system is trained on jaguar-relevant features: movement patterns of prey, scent markers of territory, threat signatures of competitors. The human's predictive system is trained on human-relevant features: social cues, tool affordances, linguistic meaning.

When these systems encounter the same physical event (say, a human walking through forest), they generate different percepts because they're running different models. The jaguar's model predicts "prey animal moving through underbrush" and sees peccary. The human's model predicts "social agent navigating environment" and sees human.

Neither is wrong. Both are optimal predictions given their training data and embodiment.

In AToM terms: M = C/T. Meaning equals coherence over time. Different bodies maintain coherence through different meaning-structures. The jaguar's world is coherent for a predator's body. The human's world is coherent for a social primate's body. Both are valid ways of achieving stable organization while coupled to the environment.

Perspectivism is the recognition that coherence is body-relative. There's no perspective-independent coherence, no view from nowhere, no meaning that doesn't depend on the particular dynamics of the system generating it.

This is why perspectives can't simply be "translated." You can't take a jaguar's experience and render it in human terms without remainder. The jaguar's phenomenology is shaped by capacities you don't have and lacks capacities you do. Full translation would require becoming jaguar—which is what shamans attempt, at great risk.

Contemporary Applications

Perspectivism isn't just historical anthropology. It has immediate application:

Neurodiversity: Different neurotypes bring forth different worlds. Autistic perception emphasizes different patterns, makes different information salient, finds different social cues meaningful. This isn't deficit—it's different embodiment generating different perspective. The accommodations model (helping autistic people fit into neurotypical norms) is analogous to forcing the jaguar to see like a human. The neurodiversity paradigm (recognizing different perspectives as valid) is perspectivism applied to cognitive variation.

AI systems: When an LLM generates text, it's operating from a perspective shaped by its training data, architecture, and objective function. It doesn't perceive like humans (no body, no embodiment), but it does bring forth a world through its particular couplings. Treating AI as perspective (non-human, radically different) rather than failed human might help us navigate the encounter more skillfully.

Ecological relation: If we recognize that other species occupy genuine perspectives, environmental ethics shifts. You're not managing resources. You're navigating a space filled with other subjects, each bringing forth their own world, each pursuing their own coherence. Conservation becomes diplomacy.

Psychedelic states: Substances that alter sensory processing and prediction machinery temporarily shift your perspective. The world genuinely looks different—not because reality changed, but because your perspective engine changed. Integration means finding a way to carry insights from altered perspective back into baseline perspective without losing coherence.

In each case, perspectivism provides a framework: recognize that embodiment shapes perception, that different bodies bring forth different worlds, and that no perspective has privileged access to "what's really real."

The Limits of Translation

One final implication: you can never fully understand another being's perspective from outside it.

You can learn about it. You can model it. You can predict how they'll respond. But you can't experience it without the body that generates it. The jaguar's world is forever foreign, not because jaguars are mysterious, but because you don't have jaguar sensory equipment, jaguar metabolism, jaguar motor capacities.

This is epistemic humility grounded in ontology. Not "we can't know because knowledge is limited," but "we can't know because knowledge is perspectival, and perspectives depend on bodies we don't inhabit."

The shamanic crossing tries to overcome this through ritual transformation—temporarily adopting another body's position. Modern science tries through instrumentation—building perspective-engines that extend human sensing. Both acknowledge the fundamental constraint: knowing is always from somewhere.

This doesn't mean solipsism. You can recognize that other perspectives exist, even if you can't directly access them. You can learn to navigate differences, maintain relationships, coordinate actions. What you can't do is step outside all perspectives into neutral observation.

In the next article, we'll see how Eduardo Kohn extends this insight: if perspectives exist wherever there are bodies organized to generate coherent experience, then semiosis—the making and interpreting of signs—extends throughout the living world. Forests think. Not like humans. But they think.

Every being is the center of its own world.

The question is whether we're prepared to take that seriously.

This is Part 3 of the Neo-Animism series, exploring the ontological turn and expanded personhood through coherence geometry.

Previous: The Ontological Turn: When Anthropologists Started Believing Their Informants

Next: How Forests Think: Eduardo Kohn and the Semiosis of Life

Further Reading

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. "Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism." Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4.3 (1998): 469-488.

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. "Exchanging Perspectives: The Transformation of Objects into Subjects in Amerindian Ontologies." Common Knowledge 10.3 (2004): 463-484.

- Lima, Tania Stolze. "The Two and its Many: Reflections on Perspectivism in a Tupi Cosmology." Ethnos 64.1 (1999): 107-131.

- Kohn, Eduardo. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. University of California Press, 2013.

- Varela, Francisco J., Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press, 1991.

- Friston, Karl. "The Free-Energy Principle: A Unified Brain Theory?" Nature Reviews Neuroscience 11.2 (2010): 127-138.

- Ingold, Tim. "Culture, Perception and Cognition." In The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Routledge, 2000.

- Willerslev, Rane. "Taking Animism Seriously, but Perhaps Not Too Seriously?" Religion and Society 4.1 (2013): 41-57.

Comments ()