Peter Zeihan: Contemporary Geopolitics

Peter Zeihan makes a provocative claim: the world order that has existed since 1945 is ending, and most countries aren't ready.

For nearly 80 years, the United States guaranteed global security—open sea lanes, stable trade, protection for allies. This wasn't altruism; it was Cold War strategy. America created a system where allies could prosper, binding them against the Soviet Union. In exchange, they accepted American leadership.

But the Cold War ended. And Zeihan argues that America no longer needs the system it created. With shale energy, favorable demographics, and unmatched geographic advantages, the US can thrive while the rest of the world fragments. The question isn't whether America will remain engaged—it's what happens when it withdraws.

American Geographic Exceptionalism

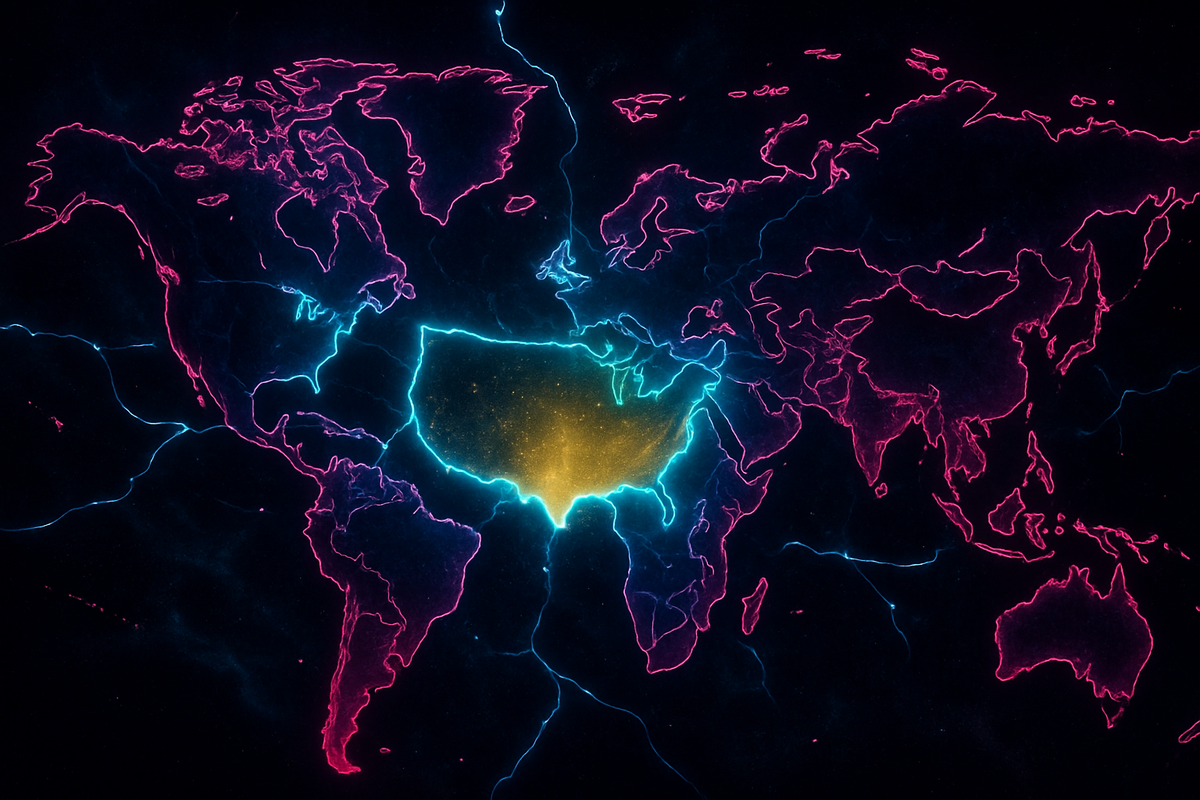

Zeihan's core argument starts with a map of the United States:

The ocean moats. America is protected by two oceans from any serious invasion threat. No other major power enjoys this security. Russia fears invasion across the North European Plain. China worries about its coastal vulnerabilities. America can sleep peacefully.

The river system. The Mississippi-Missouri-Ohio river network is the world's largest system of navigable waterways. More miles of navigable rivers than the rest of the world combined. This enabled cheap internal transport before railroads and still provides massive logistical advantage.

The neighbors. Canada and Mexico are friendly or weak. No American resources go to defending against land invasion. Compare this to Germany, surrounded by rivals, or China, with contested borders on multiple fronts.

The farmland. The American Midwest is the world's most productive agricultural region. Temperate climate, rich soil, adequate rainfall, connected by that river system. America doesn't just feed itself—it exports massively.

The energy. The shale revolution made America the world's largest oil and gas producer. Energy independence means America doesn't need Middle Eastern oil—removing one of the main reasons for global engagement.

The demographics. While Europe, China, Japan, and Korea face demographic collapse, American population continues to grow through immigration and higher birth rates. A shrinking workforce constrains economies; America doesn't have that problem.

This isn't just good luck—it's structurally unmatched advantage. No other country has all these features. Most have serious disadvantages in multiple areas.

Zeihan's point isn't American triumphalism—it's structural analysis. America isn't better; it's luckier. The geographic lottery gave it winning numbers. Other countries can work hard and make smart decisions, but they can't change their position on the map. America's rivals face headwinds that America doesn't, and that gap matters enormously.

The End of the Postwar Order

Zeihan argues that the American-led global order was historically anomalous and is now ending:

The order was a bribe. After WWII, America essentially paid other countries to be allies by guaranteeing their security and opening American markets. This was expensive but worthwhile during the Cold War.

The bribe no longer makes sense. With the Soviet Union gone and America energy-independent, why maintain the system? From a pure American interest perspective, global engagement is a cost without commensurate benefit.

Allies have become competitors. Germany, Japan, South Korea—these former recovery projects are now economic rivals. American workers compete with subsidized imports from countries America defends.

The populist turn reflects this. Trump's "America First" rhetoric resonated because it articulated what many Americans felt: why are we defending rich countries that compete with us? Zeihan argues this isn't temporary populism but recognition of structural realities.

The implication: America will increasingly withdraw from global commitments. Not because of ideology, but because geography and economics no longer require engagement.

This shift transcends political parties. Obama began the "pivot" away from the Middle East. Trump articulated withdrawal most explicitly. Biden continued many Trump-era trade policies. The direction is bipartisan because it reflects structural pressures, not partisan preferences.

The Coming Disorder

If America withdraws, Zeihan predicts cascading consequences:

Sea lane insecurity. The US Navy guarantees global shipping. Without that guarantee, piracy returns, shipping insurance skyrockets, and trade becomes riskier and more expensive. Countries that depend on imports—which is most countries—face disruption.

Energy competition. Most of the world depends on Middle Eastern oil transported through chokepoints America protects. Without American security, those oil flows become contested. Countries will have to secure their own energy supplies—or fight for them.

Demographic collapse. China, Russia, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Italy—all face shrinking workforces and aging populations. Economic dynamism requires workers. Without immigration (which these countries resist) or higher birth rates (which aren't appearing), these economies will contract.

Regional conflicts. American presence suppresses conflicts that would otherwise occur. Remove America, and old rivalries resurface. Japan-Korea tensions. Saudi-Iranian competition. European states no longer constrained by alliance. India-Pakistan. Turkey-Greece.

Food insecurity. Global agriculture depends on fertilizers, fuels, and transport that American security underwrites. Disruption to any of these threatens harvests. Countries that import food—which is most—face potential famine.

Zeihan's vision is dark: a world fragmenting into regional blocs, competing for resources, unable to maintain the trade flows that enabled globalization. Winners and losers will be determined largely by geography—who has food, energy, defensible borders, and young populations.

This isn't science fiction—it's the historical norm. The postwar American order was the anomaly. For most of human history, countries secured their own trade, fought for resources, and maintained spheres of influence. We might simply be reverting to normal after an unusual period of hegemonic stability.

Winners and Losers

In Zeihan's framework:

America wins. Energy self-sufficient, food secure, protected by oceans, with favorable demographics. America can watch the world burn and still prosper. Not pleasant, but true.

France wins. Nuclear power provides energy. Diverse agriculture provides food. Mediterranean climate attracts immigration. France doesn't depend on the global order the way Germany does.

Argentina could win. Enormous agricultural potential, no serious enemies, young population—if it can ever get its governance right. Geography offers advantages Argentina hasn't exploited.

Germany loses. Export-dependent economy requires open trade. Energy-poor: depends on Russian gas and imported oil. Aging population. Surrounded by potential rivals. Germany prospered under American order; without it, Germany faces painful adjustment or worse.

China loses. Imports most of its oil through straits America controls. Terrible demographics—the one-child policy created a demographic time bomb now detonating. Food-insecure. Surrounded by American allies. China's rise required American order; its continued rise requires that order to persist.

Zeihan is particularly bearish on China—arguing its challenges are structural and unsolvable. The coastal export economy depends on American consumer markets and American naval protection of shipping lanes. Remove either, and China's model breaks. Add demographic collapse, and Zeihan sees not continued rise but crisis.

Japan loses. Even worse demographics than China. Imports nearly all energy. Food-insecure. Protected by America against China—without that protection, vulnerable. Japan's postwar miracle was built on American security; that foundation is crumbling.

Middle East fragments. Without outside powers maintaining order, regional rivalries explode. Saudi-Iran competition goes hot. Smaller states get squeezed. Oil production disrupted by conflict.

Criticisms of Zeihan

Zeihan is controversial, and critics raise legitimate objections:

Too deterministic. Geography matters, but so do choices. Countries have overcome geographic disadvantages. Zeihan sometimes reads inevitability into contingency.

American withdrawal isn't automatic. Zeihan assumes America will disengage because geography permits it. But politics, ideology, and elite interests might sustain engagement. The national security establishment wants to stay engaged.

Underestimates adaptation. Countries facing Zeihan's pressures will adapt—new energy sources, new trade partners, new alliances. History is full of comebacks from unpromising positions.

Overconfident predictions. Zeihan makes specific predictions (China will collapse, Germany will fail) that are testable and might prove wrong. Forecasting complex systems is hard; Zeihan sometimes seems too certain.

Selection bias in examples. Zeihan emphasizes cases that support his thesis and downplays counterexamples. Countries with poor geography sometimes succeed; countries with good geography sometimes fail.

Nuclear weapons complicate everything. Zeihan focuses on conventional geographic factors but nuclear weapons change the game. Countries that might otherwise be invaded can deter. This affects the calculations significantly.

Technology could change constraints. Renewable energy could reduce dependence on oil transport. Automation could offset demographic decline. Vertical farming could alter food geography. Zeihan assumes current technological constraints persist; they might not.

The Value of Zeihan's Framework

Despite criticisms, Zeihan offers valuable perspectives:

Geography as constraint. Politicians promise many things; geography limits what's possible. Understanding geographic constraints helps assess which promises are realistic.

Demographics as destiny. Population pyramids are remarkably predictive. A country with collapsing birth rates will face specific challenges regardless of policy. Zeihan forces attention to these slow-moving but powerful trends.

Energy as foundation. Modern economies run on energy. Countries that produce it have advantages; countries that import it have vulnerabilities. Energy security isn't optional.

American advantage is real. Whatever one thinks of Zeihan's predictions, his description of American geographic advantages is accurate. America really does have unmatched endowments. Understanding this contextualizes American behavior.

The order isn't permanent. The postwar system feels natural because it's all most people have known. But it's historically unusual and not guaranteed to persist. Planning should account for possible fragmentation.

Vulnerability assessment is useful. Even if you reject Zeihan's predictions, asking "what would happen to my country/company/industry if global trade disrupted?" is valuable. Identifying dependencies clarifies risks. Many businesses and governments haven't done this analysis—and they should.

The Takeaway

Peter Zeihan applies geographic thinking to contemporary geopolitics, arguing that American advantages are structural and permanent while the challenges facing other countries are severe and worsening.

His core insight: the global order that enabled modern prosperity was a specific historical arrangement that may not persist. If America withdraws, the consequences for countries dependent on that order could be catastrophic.

Whether Zeihan's specific predictions prove correct, his framework forces attention to fundamentals: geography, demography, energy, food. These unglamorous factors constrain what politics can achieve. Understanding them helps distinguish realistic scenarios from wishful thinking.

The framework is also democratizing—anyone can look at a country's demographics, energy balance, and geographic position and make informed assessments. You don't need classified intelligence or insider access. The fundamentals are public. This makes geopolitical analysis accessible in a way that ideological or personality-based analysis isn't.

The map hasn't changed since Zeihan started writing, and his analysis remains uncomfortably relevant. Whether one accepts his conclusions or not, the questions he raises deserve serious engagement.

Zeihan is frequently wrong about specifics and timing—his predictions about imminent Chinese collapse, for instance, have been premature. But his structural analysis has proven durable. The pressures he identified continue operating. The tensions he described have intensified. Even if the timeline is wrong, the underlying logic may be right.

Further Reading

- Zeihan, P. (2014). The Accidental Superpower. Twelve. - Zeihan, P. (2016). The Absent Superpower. Zeihan on Geopolitics. - Zeihan, P. (2022). The End of the World Is Just the Beginning. Harper Business.

This is Part 3 of the Geography of Power series. Next: "Tim Marshall: Prisoners of Geography"

Comments ()