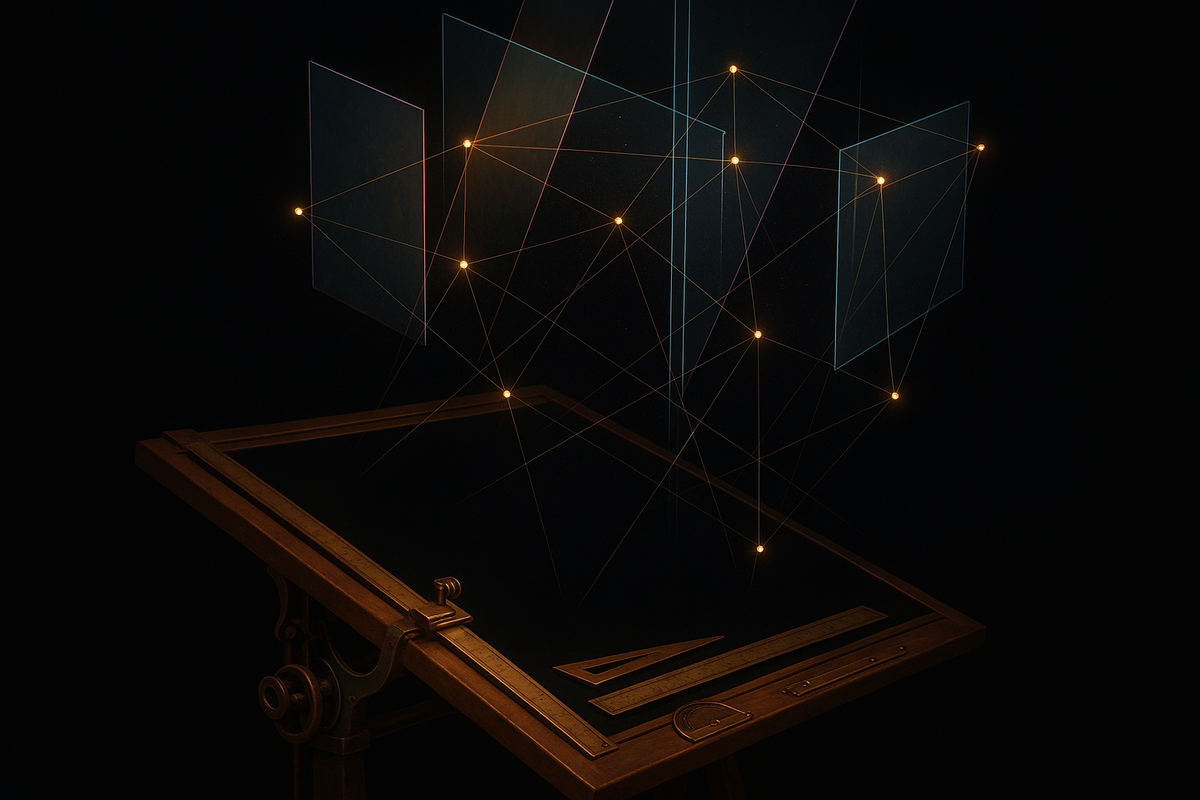

Points Lines and Planes: The Building Blocks of Space

A point has no size. A line has no width. A plane has no thickness.

This should bother you. How can something with no size be the foundation of geometry — a subject entirely about size and shape?

Here's the unlock: points, lines, and planes aren't things. They're ideas about location. A point isn't a tiny dot. It's the concept of "exactly here and nowhere else." A line isn't a thin mark. It's "all the places you pass through when you go perfectly straight forever."

You can't see a point. You can only see drawings of points — little dots that are actually circles with area. Real points have no dimension at all. They're pure position.

Once you stop thinking of these as objects and start thinking of them as concepts, geometry opens up.

Why Zero Dimensions?

The dimension of something is how many independent directions you can move within it.

On a plane, you can move north-south or east-west. Two directions. Two dimensions.

On a line, you can only move back and forth. One direction. One dimension.

At a point? You can't move at all and stay on the point. Zero directions. Zero dimensions.

This is why a point has "no size" — size requires at least one dimension to exist in. A point is the minimum: location without extension.

Lines: One Dimension of Freedom

A line is what you get when you allow movement in exactly one direction.

Pick a point. Now pick a direction. Move that way forever, and also forever in the opposite direction. That's a line.

Every line is:

- Straight: It never curves

- Infinite: It goes forever in both directions

- Determined by two points: Any two points define exactly one line

That last property is crucial. It's Euclid's first postulate: between any two points, there exists exactly one straight line. This seems obvious, but it's actually a statement about the structure of space. In curved spaces, it's not always true.

The Difference Between Lines, Rays, and Segments

Geometry distinguishes three related concepts:

Line: Extends infinitely in both directions. No endpoints.

Ray: Starts at a point and extends infinitely in one direction. One endpoint.

Line segment: Starts at a point, ends at another point. Two endpoints.

When you draw a "line" on paper, you're actually drawing a line segment — a finite portion of the infinite object. The arrows on both ends are the convention for "this keeps going."

Planes: Two Dimensions of Freedom

A plane is what you get when you allow movement in two independent directions.

Pick a point. Pick two directions that aren't the same (and aren't opposite). Move freely in any combination of those directions, forever. That's a plane.

Every plane is:

- Flat: It never curves

- Infinite: It extends forever in all directions within it

- Determined by three points: Any three non-collinear points define exactly one plane

"Non-collinear" means the three points don't all lie on the same line. If they did, infinitely many planes would pass through them — just rotate around the line they share.

How Points, Lines, and Planes Interact

This is where geometry gets interesting. These primitives relate to each other in specific ways:

Two points determine exactly one line.

Two lines either:

- Intersect at exactly one point (if they cross)

- Are parallel (never meet, same plane)

- Are skew (never meet, different planes — only in 3D)

Three points determine exactly one plane (if non-collinear).

Two planes either:

- Intersect in exactly one line

- Are parallel (never meet)

A line and a plane either:

- Intersect at exactly one point

- The line lies entirely in the plane

- Are parallel (never meet)

These relationships aren't arbitrary. They follow from the definitions and the properties of flat space.

Collinear and Coplanar

Two important terms:

Collinear: Points that lie on the same line. Any two points are automatically collinear (they define a line). Three or more points might be collinear, or might not.

Coplanar: Points that lie on the same plane. Any three points are automatically coplanar (they define a plane). Four or more points might be coplanar, or might not.

These concepts matter when you're reasoning about spatial relationships. If four points are coplanar, certain theorems apply. If they're not, the situation is fundamentally three-dimensional.

The Real Number Line

Here's where algebra and geometry first meet: you can identify each point on a line with a number.

Pick any point as zero. Pick a direction as positive. Choose a unit length. Now every point corresponds to exactly one real number — its signed distance from zero.

This is the number line, and it's a profound idea. It says that the one-dimensional geometry of a line is exactly the same as the structure of real numbers. Every real number is a point. Every point is a real number.

The number line is geometry and arithmetic unified.

Coordinates: When Lines Cross

Extend this idea to planes. Take two perpendicular lines (the axes). Their intersection is the origin, labeled (0, 0). Now every point in the plane corresponds to an ordered pair of numbers — its distances from each axis.

This is the Cartesian coordinate system, named after Descartes. It transformed geometry by letting you describe shapes with equations.

The point (3, 4) is where you end up if you go 3 units along the x-axis and 4 units along the y-axis. The equation y = x describes all points where the two coordinates are equal — a diagonal line through the origin.

Coordinates don't change the geometry. They give you a language for describing it numerically.

Why These Primitives?

You might ask: why build geometry from these particular concepts?

The answer is minimalism. Points, lines, and planes are the simplest objects with 0, 1, and 2 dimensions. Everything more complex can be built from them.

A triangle is three non-collinear points plus the line segments connecting them. A circle is all points at a fixed distance from a center point. A cube is eight points, twelve edges, six faces — all defined in terms of points, segments, and planes.

You need primitives that are too simple to decompose further. Points, lines, and planes are exactly that: the atoms of spatial reasoning.

The Idealization

Real-world objects are never truly points, lines, or planes. The tip of a needle has some width. A laser beam has some spread. A tabletop has some wobble and thickness.

But the idealization is useful precisely because it strips away the irrelevant details. When you analyze a bridge's structure, you don't care about the molecular composition of the steel. You care about the geometric relationships between components.

Points, lines, and planes are tools for thinking about space at the level of relationship and structure. They're not claims about what exists. They're a language for describing how space works.

The Foundation

Everything in geometry rests on these three concepts:

A point is pure location — zero-dimensional, no size, just "here."

A line is pure direction — one-dimensional, infinite, perfectly straight.

A plane is pure flatness — two-dimensional, infinite, perfectly flat.

From these, you build angles (where lines meet), triangles (three points connected), circles (points equidistant from a center), and ultimately all the shapes geometry studies.

The building blocks have no size. But what you build from them describes the entire structure of space.

Part 2 of the Geometry series.

Previous: What Is Geometry? The Mathematics of Space and Shape Next: Angles: Measuring the Space Between Lines

Comments ()