Power Series: Polynomials That Go On Forever

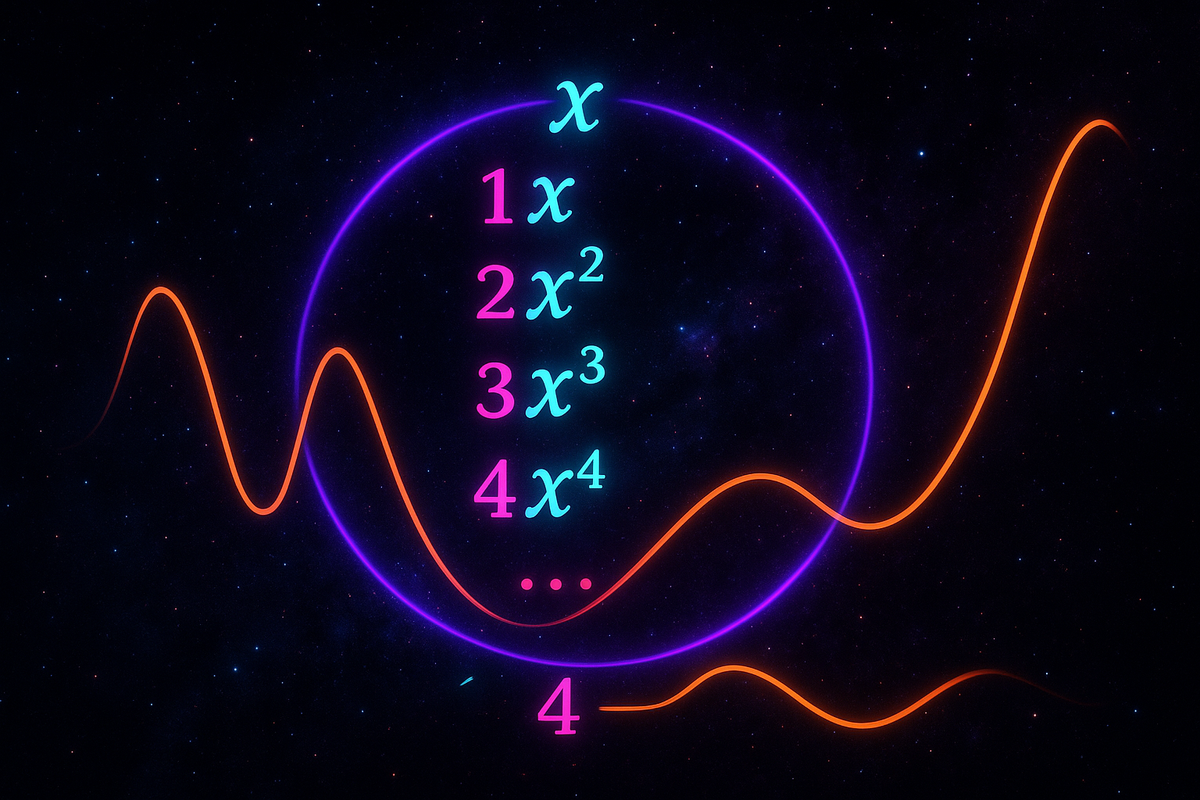

A power series is a polynomial that never ends.

f(x) = 1 + x + x² + x³ + x⁴ + ...

Polynomials stop. This doesn't. It's an infinite sum of powers of x.

And here's the remarkable thing: many functions you know—sin, cos, eˣ, ln—can be written as power series. The smooth functions of calculus are, in a precise sense, infinite polynomials.

This is the power series insight: infinity turns polynomials into something universal.

The Form of a Power Series

A power series centered at a = 0 looks like:

∑ₙ₌₀^∞ cₙxⁿ = c₀ + c₁x + c₂x² + c₃x³ + ...

The coefficients cₙ are constants. The variable x is what changes.

Centered at a different point a:

∑ₙ₌₀^∞ cₙ(x-a)ⁿ = c₀ + c₁(x-a) + c₂(x-a)² + ...

This is the same idea, just shifted to center at x = a instead of x = 0.

The question is always: For which values of x does this series converge?

Radius of Convergence

Every power series has a radius of convergence R.

- The series converges for |x| < R

- The series diverges for |x| > R

- At |x| = R, you have to check endpoints individually

The radius can be 0, any positive number, or ∞.

R = 0: Series only converges at x = 0. Useless.

R = ∞: Series converges for all x. The series for eˣ works everywhere.

R = finite: Series works in an interval. The series for ln(1+x) works for -1 < x ≤ 1.

The ratio test often finds R. For ∑cₙxⁿ:

R = lim |cₙ/cₙ₊₁| (if the limit exists)

The Geometric Series as Power Series

The simplest power series is the geometric series:

1 + x + x² + x³ + ... = 1/(1-x), for |x| < 1

This is a power series with cₙ = 1 for all n. It converges when |x| < 1, giving radius R = 1.

From this one series, you can derive many others by substitution, differentiation, and integration.

Replace x with -x: 1 - x + x² - x³ + ... = 1/(1+x)

Replace x with x²: 1 + x² + x⁴ + x⁶ + ... = 1/(1-x²)

The geometric series is the mother of power series.

Maclaurin Series: Centered at 0

A Maclaurin series is a power series centered at x = 0, where the coefficients come from derivatives of a function:

f(x) = ∑ₙ₌₀^∞ (f⁽ⁿ⁾(0)/n!) xⁿ

= f(0) + f'(0)x + f''(0)x²/2! + f'''(0)x³/3! + ...

The coefficients are cₙ = f⁽ⁿ⁾(0)/n!.

Why this works: The series is constructed so that its derivatives at 0 match the function's derivatives at 0. If all derivatives match, the function and series are the same.

Famous Maclaurin Series

Exponential: eˣ = 1 + x + x²/2! + x³/3! + x⁴/4! + ...

Converges for all x. Radius R = ∞.

Sine: sin(x) = x - x³/3! + x⁵/5! - x⁷/7! + ...

Only odd powers, alternating signs. Radius R = ∞.

Cosine: cos(x) = 1 - x²/2! + x⁴/4! - x⁶/6! + ...

Only even powers, alternating signs. Radius R = ∞.

Natural logarithm: ln(1+x) = x - x²/2 + x³/3 - x⁴/4 + ...

Converges for -1 < x ≤ 1. Radius R = 1.

Arctangent: arctan(x) = x - x³/3 + x⁵/5 - x⁷/7 + ...

Converges for |x| ≤ 1. Radius R = 1. At x = 1, gives π/4.

Taylor Series: Centered Anywhere

A Taylor series is centered at x = a:

f(x) = ∑ₙ₌₀^∞ (f⁽ⁿ⁾(a)/n!) (x-a)ⁿ

This is useful when you want to approximate a function near a point other than 0.

Example: The Taylor series for ln(x) centered at a = 1:

ln(x) = (x-1) - (x-1)²/2 + (x-1)³/3 - ...

This converges for 0 < x ≤ 2.

Taylor series are Maclaurin series shifted to a different center.

Operations on Power Series

Addition: Add coefficient by coefficient.

Multiplication: Cauchy product (like polynomial multiplication, but infinite).

Differentiation: Differentiate term by term.

If f(x) = ∑cₙxⁿ, then f'(x) = ∑ncₙxⁿ⁻¹.

The radius of convergence stays the same.

Integration: Integrate term by term.

∫f(x)dx = C + ∑cₙxⁿ⁺¹/(n+1).

Again, same radius.

This is powerful. Differentiating and integrating power series is easy—just apply the power rule to each term.

Finding Power Series

Method 1: Compute derivatives

Calculate f(0), f'(0), f''(0), ... and use cₙ = f⁽ⁿ⁾(0)/n!.

Method 2: Use known series

Substitute into known series, differentiate, integrate.

Example: Find the series for 1/(1+x²).

Start with 1/(1-u) = 1 + u + u² + ... and substitute u = -x²:

1/(1+x²) = 1 - x² + x⁴ - x⁶ + ...

Method 3: Multiply series

To find eˣsin(x), multiply the series for eˣ and sin(x) term by term.

Why Power Series Matter

- They approximate functions. Truncating a power series gives polynomial approximations. sin(x) ≈ x - x³/6 works well for small x.

- They solve differential equations. Many differential equations have power series solutions when closed-form solutions don't exist.

- They define functions. eˣ can be defined by its power series. This is how complex exponentials work.

- They compute values. Calculators use power series to evaluate sin, cos, exp. Truncate the series for the desired precision.

- They reveal structure. The power series for eˣ shows why its derivative equals itself. Each term's derivative gives the previous term.

Convergence vs. Representation

A power series may converge but not equal the function everywhere.

Example: f(x) = e^(-1/x²) for x ≠ 0, f(0) = 0.

All derivatives at 0 are 0. The Maclaurin series is 0 + 0x + 0x² + ... = 0.

But f(x) ≠ 0 for x ≠ 0. The series converges but doesn't represent the function.

Functions whose Taylor series equal them everywhere are called analytic. Most functions you encounter in practice are analytic, but not all.

The Power of Infinite Polynomials

Power series say: polynomials aren't limited. Let them go on forever, and they can represent the transcendental functions—exp, log, sin, cos.

The finite polynomials are dense enough in function space that, by taking limits, they can approximate anything smooth.

This is the deep truth: smooth functions are secretly infinite polynomials. The calculus of derivatives and integrals—applied infinitely—recovers them exactly.

Part 10 of the Sequences Series series.

Previous: Convergence Tests: When Does an Infinite Series Have a Sum? Next: Recursion: Sequences Defined by Their Own Terms

Comments ()