Protein Folding: Free Energy's Masterpiece

A protein emerges from the ribosome as a linear chain of amino acids. Within milliseconds to seconds, it folds into a precise three-dimensional structure—a shape that determines its function.

This is the protein folding problem, and it's fundamentally a free energy problem. The native structure is the free energy minimum. The amino acid sequence encodes a free energy landscape that guides the chain to its destination.

Understanding protein folding through Gibbs free energy reveals how nature solves a combinatorial impossibility, why some proteins misfold into disease, and how evolution sculpts molecular machines from thermodynamic gradients.

Levinthal's Paradox

Consider a small protein of 100 amino acids. Each amino acid can adopt perhaps 3 backbone conformations. The total number of possible conformations: 3^100 ≈ 10^47.

If the protein sampled one conformation per picosecond (10^-12 seconds), exploring all possibilities would take 10^27 years—longer than the universe has existed.

Yet proteins fold in milliseconds to seconds.

This is Levinthal's paradox: random searching cannot explain protein folding. The search must be guided.

The pebble: Proteins don't find their structure by exploring all possibilities. They follow the free energy gradient downhill. The answer isn't search—it's thermodynamics.

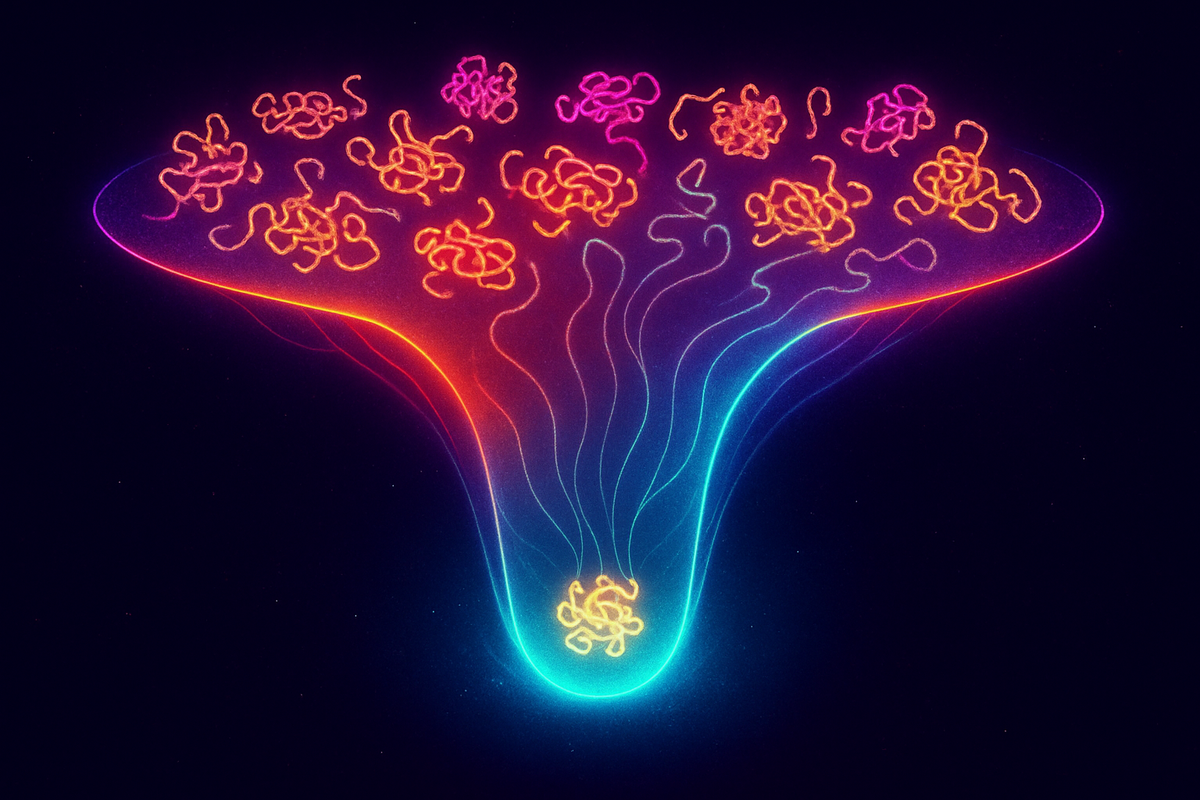

The Folding Funnel

Christian Anfinsen showed in the 1960s that protein structure is determined by sequence alone. A denatured protein, given proper conditions, will refold to its native structure. The sequence contains all the information.

The modern view: the amino acid sequence defines a free energy landscape. The unfolded state sits at high free energy with many conformations. The native state sits at the global minimum with essentially one conformation.

Between them: a funnel. The landscape slopes downward toward the native state from (almost) everywhere. Local traps exist, but the overall gradient points home.

This funnel picture resolves Levinthal's paradox. The protein doesn't search randomly; it rolls downhill. At each step, conformations with lower free energy are favored. The funnel guides the chain to its destination without exploring alternatives.

Thermodynamics of Folding

For folding to be spontaneous:

ΔG_folding = ΔH_folding - TΔS_folding < 0

The enthalpy contribution (ΔH_folding): - Favorable: Hydrogen bonds form, van der Waals contacts optimize, salt bridges form - Unfavorable: Burying charged groups, straining bond angles

Net ΔH_folding is typically small and can be positive or negative.

The entropy contribution (ΔS_folding): - Unfavorable: The chain loses conformational freedom (huge effect, ~100-1000 conformations → 1) - Favorable: The hydrophobic effect releases ordered water

The folded protein has vastly less conformational entropy than the unfolded chain. This should make folding unfavorable. So what drives folding?

The pebble: Proteins fold because of water, not despite it. The hydrophobic effect—releasing ordered water molecules when hydrophobic residues bury themselves—provides the entropic driving force.

The Hydrophobic Effect

In unfolded proteins, hydrophobic amino acids (leucine, valine, phenylalanine, etc.) are exposed to water. Water molecules must form ordered "cages" around these nonpolar surfaces, reducing water's entropy.

When the protein folds, hydrophobic residues cluster in the interior, away from water. The ordered water is released, increasing entropy.

ΔS_water > 0 (favorable)

This hydrophobic effect is the dominant driving force for most proteins. The entropy cost of constraining the chain is paid by the entropy gain of liberating water.

Quantitatively: - ΔS_chain ≈ -200 to -500 J/(mol·K) (unfavorable) - ΔS_water ≈ +300 to +600 J/(mol·K) (favorable) - ΔS_total ≈ +50 to +150 J/(mol·K) (favorable)

Folding increases total entropy, despite reducing protein entropy.

Marginal Stability

A striking fact: most proteins are only marginally stable.

ΔG_folding ≈ -20 to -60 kJ/mol

For a 100-residue protein with thousands of interactions, the net stabilization energy is equivalent to just a few hydrogen bonds. The enormous favorable contributions are almost entirely canceled by enormous unfavorable contributions.

This marginal stability is not a bug—it's a feature. Proteins need to: - Fold (requires ΔG < 0) - Unfold for degradation (requires not too negative) - Be flexible for function (requires not too stable) - Respond to regulation (requires accessibility)

Extreme stability would create rigid, non-functional, non-degradable molecules. Evolution fine-tunes stability to the minimum necessary.

The pebble: Proteins aren't as stable as they could be. They're as stable as they need to be—any more would make them rigid and unresponsive.

Temperature Dependence

Proteins can unfold at both high and low temperatures.

Heat denaturation: At high T, the TΔS term dominates. The entropy cost of folding (chain conformational restriction) becomes unsupportable.

Cold denaturation: At low T, the hydrophobic effect weakens. Water can form ordered cages without much entropy cost when T is low. The main driving force for folding diminishes.

The stability curve ΔG(T) is typically parabolic, with maximum stability around room temperature. This is why organisms have optimal temperature ranges—their proteins unfold outside them.

Chaperones: Kinetic Assistance

The thermodynamic minimum is the native state. But kinetics matter too. Proteins can get trapped in local minima—misfolded states that are metastable.

Molecular chaperones help proteins avoid these traps:

Hsp70 binds to exposed hydrophobic regions, preventing aggregation during folding. ATP hydrolysis drives cycles of binding and release.

Chaperonins (GroEL/GroES) encapsulate unfolded proteins in a chamber, allowing them to fold in isolation. ATP hydrolysis powers the cycle.

Hsp90 assists late-stage folding and stabilizes nearly-native conformations.

Chaperones don't change the thermodynamic destination—the native state is still the free energy minimum. They change the kinetics, helping proteins find the minimum rather than getting stuck.

Protein Misfolding Diseases

When proteins fold wrong and aggregate, disease results:

Alzheimer's disease: β-amyloid and tau proteins form aggregates (plaques and tangles).

Parkinson's disease: α-synuclein aggregates into Lewy bodies.

Prion diseases: PrP protein converts to an aggregation-prone form that templates further misfolding.

Type 2 diabetes: Islet amyloid polypeptide aggregates in pancreatic islets.

These aggregates are not the free energy minimum of a single protein. But for the aggregate system, they can be lower in free energy than many separate native proteins. The thermodynamics of aggregation differs from the thermodynamics of folding.

Aggregation is typically kinetically limited—slow nucleation followed by rapid growth. Once a nucleus forms, it catalyzes further misfolding. This is why misfolding diseases are progressive.

AlphaFold and the Folding Problem

In 2020, DeepMind's AlphaFold achieved near-experimental accuracy in predicting protein structures from sequences. Did it solve the folding problem?

Yes and no.

Yes: We can now predict structures for almost any sequence. The practical problem—given sequence, what's the structure?—is largely solved.

No: AlphaFold doesn't simulate the folding process. It doesn't explain why the sequence encodes that structure or how the protein navigates the landscape. The physics of the free energy funnel remains a research frontier.

AlphaFold learned patterns from known structures. It's pattern matching at superhuman scale. Understanding how physics determines those patterns is still ongoing.

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

Not all proteins fold. Perhaps 30-40% of the human proteome contains disordered regions that don't adopt stable structures.

These intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) have shallow free energy landscapes. No deep minimum exists. They sample many conformations without settling.

IDPs aren't broken—they're functional. Their disorder enables: - Binding to multiple partners (flexible recognition) - Rapid assembly and disassembly - Post-translational modification sites - Phase separation into membrane-less organelles

The absence of a folding minimum is itself evolutionarily selected. Not all proteins need a single structure.

Free Energy Perturbation Methods

Computational chemistry calculates ΔG of folding through various methods:

Molecular dynamics simulates atomic motions, sampling the free energy landscape. Challenging because folding takes microseconds to seconds, while simulations are limited.

Free energy perturbation calculates ΔG differences between similar states—useful for understanding mutations.

Enhanced sampling (metadynamics, replica exchange) accelerates rare events, allowing exploration of the landscape.

These methods increasingly match experimental values. The physics of protein folding is becoming computable.

Protein Engineering

Understanding ΔG enables protein design:

Stabilizing mutations: Reduce ΔG_folding (more negative). Fill cavities, optimize hydrogen bonding, increase hydrophobic packing.

Destabilizing mutations: Increase ΔG_folding. Often introduce steric clashes or unfavorable charges.

De novo design: Create new proteins from scratch by optimizing the free energy landscape. Recent successes include new folds not found in nature.

Directed evolution: Screen random mutations for desired properties. Lets evolution optimize what we can't calculate.

Enzyme engineering, therapeutic proteins, materials science—all benefit from thermodynamic understanding of folding.

Summary

Protein folding is a free energy problem:

- The native structure is the global free energy minimum - The hydrophobic effect provides the main driving force - Marginal stability enables function - Chaperones help kinetics match thermodynamics - Misfolding diseases arise when aggregates have lower free energy than native states - AlphaFold predicts structures; physics explains why

The pebble: A protein's fold is a theorem, proved by thermodynamics. The sequence states the axioms; the native structure is the conclusion; and every intermediate is a step in the proof, guided by free energy downhill.

Further Reading

- Dill, K. A. & MacCallum, J. L. (2012). "The protein-folding problem, 50 years on." Science, 338(6110), 1042-1046. - Finkelstein, A. V. & Ptitsyn, O. B. (2016). Protein Physics. Academic Press.

This is Part 8 of the Gibbs Free Energy series. Next: "Phase Transitions: When Free Energy Surfaces Cross"

Comments ()