Psychopathy Spectrum: It's Not Binary

Psychopathy Spectrum: It's Not Binary

The word "psychopath" conjures a specific image: Hannibal Lecter behind glass, Ted Bundy's courtroom smirk, the true crime documentary. Psychopathy is violence, predation, incarceration. It's them, not us.

Except that's not what the research shows.

Psychopathy isn't binary. It's a dimensional trait—a spectrum that exists in varying degrees across the population. Some people score high. Some score low. Most fall somewhere in the middle. And here's the kicker: psychopathic traits don't just predict violence and criminality. They also predict success. CEOs, surgeons, Special Forces operators—they score higher on psychopathic traits than the general population.

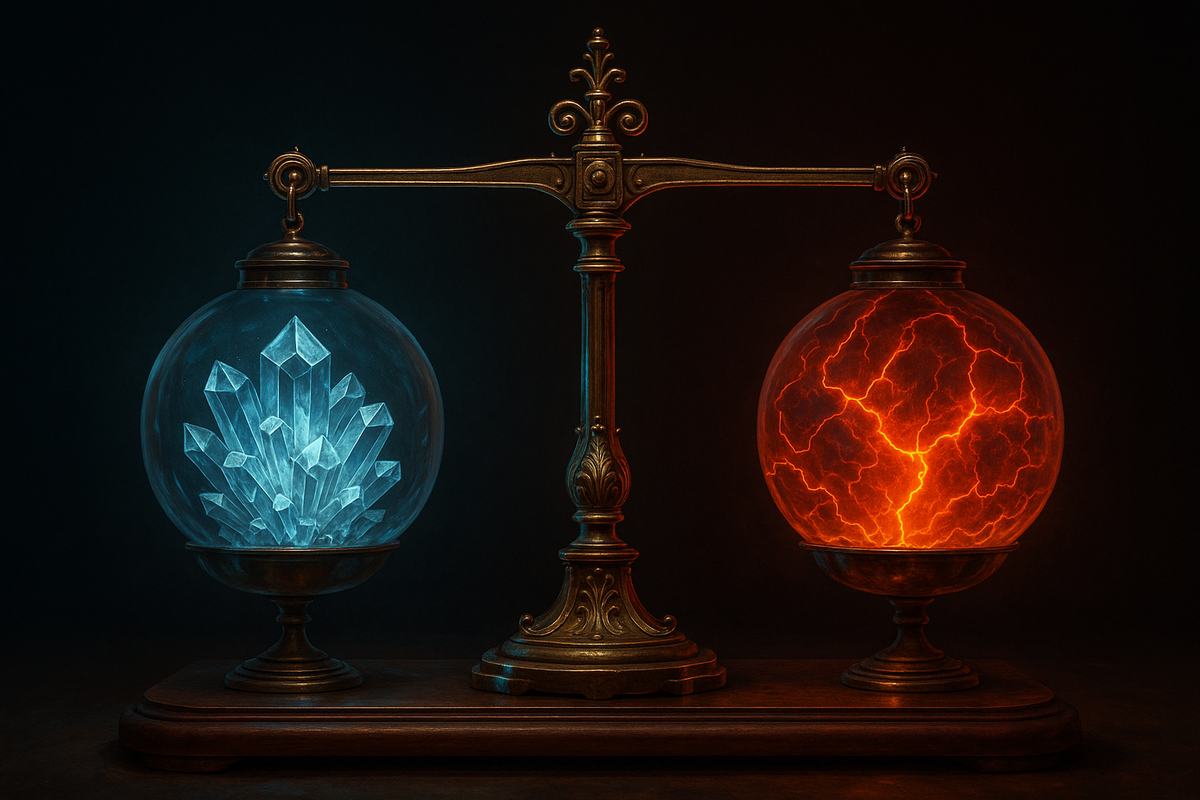

The psychopath in prison and the psychopath in the boardroom share core features but differ in one critical dimension. Understanding that difference requires unpacking psychopathy's two-factor structure: Factor 1 (the coldness—lack of empathy, no guilt, shallow emotions) and Factor 2 (the chaos—impulsivity, aggression, poor behavioral control). Factor 1 without Factor 2 gets you the boardroom. Factor 1 plus Factor 2 gets you the prison yard.

Once you see the spectrum, you start seeing it everywhere.

The Two-Factor Model: Successful vs Criminal Psychopathy

Psychopathy isn't one thing. It's two distinct dimensions that can vary independently.

Factor 1 (Interpersonal-Affective): The coldness. Lack of empathy, no guilt, superficial charm, shallow emotions. Factor 1 psychopaths understand emotions cognitively—they model them like dark empaths—but don't feel them. They know what fear looks like without experiencing it viscerally. They understand that hurting people is "wrong" without feeling the wrongness.

Factor 2 (Lifestyle-Antisocial): The chaos. Impulsivity, poor behavioral control, aggression, irresponsibility, criminal behavior. Factor 2 is the inability to delay gratification, plan ahead, or learn from consequences. It's reactive violence, reckless decision-making, and life instability.

Here's the key: you can have one without the other. High Factor 1 with low Factor 2 is coldness without recklessness. High Factor 1 with high Factor 2 is coldness plus chaos. The former gets you the boardroom. The latter gets you the prison yard.

The data is consistent:

- High Factor 1 + Low Factor 2: Leadership positions, high-pressure professions, corporate settings. Lower arrest rates, higher income.

- High Factor 1 + High Factor 2: Prisons. High recidivism. Violent offending.

- Low Factor 1 + High Factor 2: Generic antisocial behavior—more conduct disorder than psychopathy.

The difference isn't degree—it's type. Factor 1 gives you the emotional deficits. Factor 2 determines whether you can control yourself long enough to succeed. One population can delay gratification, plan strategically, and avoid detection. The other can't. Same coldness. Different outcome.

What Factor 1 Looks Like: Adaptive Psychopathy

Robert Hare developed the Psychopathy Checklist by interviewing prison inmates. One high-scoring psychopath described torturing and killing animals as a child. Hare asked if he felt remorse. The man paused, genuinely confused: "You mean, did I feel bad about it? No. Why would I? They were just animals."

That's Factor 1. Not anger. Not sadism. Just nothing. Absence where empathy should be.

But Factor 1 doesn't require violence. It's a personality configuration where emotional connections don't form, guilt doesn't register, and other people are objects with utility rather than subjects with feelings. Here's what it looks like:

Fearlessness: Low amygdala reactivity. Reduced physiological fear response. They don't startle easily, don't experience anticipatory anxiety. This makes them effective under pressure—bomb disposal, emergency surgery, combat—because fear doesn't degrade performance.

Stress tolerance: Reduced cortisol response. Where most people choke under pressure, Factor 1 psychopaths remain physiologically calm. They can make ruthless decisions without emotional interference.

Shallow affect: Emotions are brief, muted, cognitively processed rather than felt. They perform warmth, humor, concern—without feeling it. Emotions are social signals to deploy, not states to inhabit.

No guilt or remorse: Violating moral norms doesn't produce aversive affect. They understand intellectually that certain actions are "wrong" but don't feel the wrongness. Conscience is a concept, not a force.

Manipulativeness: Strategic lying and exploitation without emotional cost. Because they don't experience guilt or empathic concern, manipulation is just effective strategy.

This profile isn't maladaptive in many environments. It's adaptive. That's why Factor 1 traits show elevated prevalence in:

- Corporate leadership: CEOs, executives, entrepreneurs

- Surgery: Trauma surgery where emotional detachment prevents performance degradation

- Military: Special operations where fear is a liability

- Finance: Traders making high-stakes decisions under pressure

- Law: Corporate attorneys where adversarial zeal requires suppressing empathy

These aren't failed psychopaths. They're successful psychopaths whose emotional deficits map onto professional demands. Their coldness is their edge.

What Factor 2 Adds: The Criminal Path

Factor 2 is where psychopathy becomes obviously maladaptive. It's impulsivity, aggression, inability to learn from consequences.

Impulsivity: Can't delay gratification. Poor inhibitory control. Short-sighted exploitation—stealing, cheating, lying—without considering detection risk.

Irresponsibility: Failure to honor commitments. Parasitic dependence. Obligation doesn't register as binding.

Poor behavioral controls: Reactive aggression. Explosive anger. Physical violence in response to perceived slights. Unlike Factor 1's cold, instrumental aggression, Factor 2 aggression is hot—emotionally driven, poorly controlled.

Early behavioral problems: Childhood conduct disorder. Aggression toward peers. Authority conflicts. Factor 2 traits emerge early and persist.

Criminal versatility: Involvement in multiple types of crime—property, violent, drugs, fraud. Opportunistic offending across domains.

Where Factor 1 produces coldness, Factor 2 produces chaos. The combination is devastating: someone who feels no guilt (Factor 1) and can't inhibit destructive impulses (Factor 2). They'll harm you without remorse and without restraint.

But here's the key: Factor 2 without high Factor 1 doesn't produce psychopathy—it produces generic antisocial behavior. The person is impulsive, aggressive, irresponsible, but they still experience emotional connections, guilt, fear. They're not cold. They're volatile.

This matters for intervention. Factor 2 traits respond somewhat to cognitive-behavioral interventions, structure, incentives. Factor 1 traits—the core emotional deficits—don't. You can teach impulse control. You can't teach empathy if the wiring isn't there.

The Neuroscience of Cold Cognition

What makes Factor 1 possible? What does a brain without empathy look like?

Amygdala hypoactivation: The amygdala processes threat, fear, emotional salience. In Factor 1 psychopaths, amygdala activation to fearful faces and distress cues is significantly reduced. They see the fear—they don't feel it.

Reduced amygdala-prefrontal connectivity: The amygdala normally talks to the prefrontal cortex to integrate emotional information into decision-making. In psychopaths, this connectivity is weakened. Emotional signals don't modulate cognition.

Blunted startle response: The involuntary jump when startled is diminished in psychopaths. Their nervous systems don't react defensively to threat.

Altered insula function: The insula supports empathic resonance—feeling what others feel. Psychopaths show reduced insula activation when viewing others in pain.

Intact prefrontal function: Unlike Factor 2 impulsivity, Factor 1 psychopaths often show normal or enhanced prefrontal function—executive control, planning, inhibition. Their emotional deficits aren't due to frontal damage. They're due to decoupled emotion-cognition circuits.

This produces cold cognition: reasoning and decision-making uncontaminated by emotional interference. In some contexts, this is an asset. You can perform surgery without your hands shaking from empathic distress. You can fire 10,000 employees without losing sleep. You can send soldiers into battle knowing some will die without being paralyzed by guilt.

In other contexts, it's catastrophic. You can torture someone without visceral aversion. You can scam elderly victims without remorse. You can abuse a partner without feeling their pain.

Same neural architecture. Different context.

The Boardroom and the Prison Yard: Context Shapes Expression

Why do some high Factor 1 individuals become CEOs while others become inmates?

Intelligence and executive function: Successful psychopaths typically have higher IQ and better executive control. Intelligence allows strategic planning, risk assessment, adaptive manipulation. Low intelligence plus high psychopathy equals impulsive offending and detection.

Socioeconomic resources: Psychopaths born into wealth, education, and social capital have infrastructure that channels their traits into legitimate success. Psychopaths born into poverty express the same traits through crime.

Cultural fit: Some industries reward psychopathic traits explicitly—corporate ruthlessness, financial risk-taking, military emotional detachment. Other environments punish those traits—community-based cultures, relationship-intensive professions.

Impulse control development: Early interventions, structured environments, and high parental monitoring can shape Factor 2 traits even in high Factor 1 individuals. If you learn to delay gratification during development, you can leverage Factor 1 coldness without Factor 2 recklessness.

The traits don't change. The expression changes based on context, resources, and opportunity.

This explains uncomfortable findings: CEOs score higher on psychopathic traits than the general population. Studies estimate 4-12% of corporate executives meet criteria for psychopathy compared to ~1% population base rate. They're not failed psychopaths. They're optimized psychopaths—high Factor 1 giving them emotional detachment and ruthless decision-making, sufficient Factor 2 control to avoid self-sabotage, and contextual fit with corporate incentive structures that reward their traits.

Same traits. Different environment. Different outcome.

Spectrum Thinking: The Subclinical Population

Most people aren't high enough on psychopathic traits to meet clinical cutoffs. But psychopathic traits exist dimensionally across the population. Everyone falls somewhere on the spectrum.

You know people who make decisions without emotional interference, don't experience guilt over moral violations, charm strategically without genuine warmth, take risks others avoid, manipulate without apparent discomfort, experience emotions briefly and move on.

These aren't "psychopaths." They're individuals with elevated psychopathic traits—high enough to notice, not high enough to meet diagnostic thresholds. Estimates suggest 10-15% of the population scores moderately high on psychopathic traits without meeting full diagnostic criteria. They're your coworker who never seems stressed, your friend who's charming but emotionally unavailable, your partner who can lie smoothly without tells.

Relationships: People with elevated psychopathic traits form relationships differently—more transactional, less emotionally intimate, more prone to infidelity and instrumental manipulation. Not because they're evil. Because deep emotional bonding doesn't happen for them. They're not pretending to be detached. They are detached.

Moral reasoning: Subclinical psychopaths understand moral rules cognitively but don't feel their bindingness. They follow rules when detection risk is high, violate them when it's safe. Morality is external constraint, not internal motivation.

Stress resilience: Elevated psychopathic traits predict lower anxiety, lower depression, better performance under pressure. This is adaptive in high-stress roles.

Exploitation risk: Even subclinical levels increase likelihood of manipulation, deception, relational harm. Moderate elevation is enough.

Spectrum thinking reveals psychopathy isn't a kind of person—it's a configuration of traits that vary continuously. The question isn't "psychopath or not"—it's "how much, which dimensions, and in what context?"

Recognizing the Spectrum: Behavioral Signatures

If psychopathy is dimensional, how do you detect elevated traits?

Emotional incongruity: Their expressed emotion doesn't match situational demands. They describe tragedies flatly. They perform concern but the timing is off—like someone following an empathy script without feeling it.

Instrumentalization: Relationships are transactional. They invest when useful, withdraw when not. Friendships are contingent on utility.

Guiltless boundary violation: They violate norms—lying, cheating, rule-breaking—without visible distress. Not defiant. Just unbothered.

Cold vs hot aggression: Factor 1 aggression is cold, calculated, instrumental. Factor 2 aggression is hot—explosive, emotional, disproportionate.

Glib charm without depth: Conversations feel engaging but oddly shallow. They mirror your interests but disclose nothing genuine.

Fearlessness in high-stakes situations: Calm when others panic. Not because they're brave—because they don't process threat the same way.

Parasitic relationships: They extract resources, labor, emotional support without reciprocating. You give, they take, the imbalance doesn't register.

The pattern: functional absence of emotional resonance paired with strategic social engagement. They're in the game, playing skillfully, but not feeling what you feel.

Psychopathy and Coherence: The Uncoupled System

Psychopaths maintain their internal coherence by decoupling from emotional feedback loops that destabilize most people.

Guilt destabilizes: For most people, violating values produces guilt, shame, cognitive dissonance—forcing costly behavioral correction. Psychopaths don't experience the destabilization. They can exploit without internal friction.

Empathy creates coupling: Affective empathy binds you to others' emotional states. Their suffering becomes your suffering, constraining behavior. Psychopaths don't couple this way. Your pain is information, not experience.

Fear regulates risk: Fear makes risky decisions aversive, keeping behavior within safe bounds. Psychopaths' blunted fear response means they take risks others avoid—adaptive when risks pay off, catastrophic when they don't.

The result: stable internal coherence decoupled from social and moral feedback. Where most people's coherence depends on alignment between behavior and values, alignment with others' states, and threat-avoidance, the psychopath's coherence is internally stabilized without these external anchors.

They're not incoherent. They're differently coherent—coherence maintained through mechanisms that don't require emotional coupling.

This makes them dangerous in relational contexts and adaptive in contexts requiring emotional detachment. Same geometry. Different environment.

What's Ahead: The Dark Spectrum in Full

We've mapped dark empaths (cognitive empathy weaponized) and psychopathy (emotional decoupling across dimensions). Next:

- Narcissism Types — Grandiose vs vulnerable narcissism look nothing alike but share core fragility

- Machiavellianism Unpacked — The strategic manipulator playing a longer game

- Malevolent Creativity — Why dark traits predict success in specific niches

- Detection Science — Behavioral signatures for identifying high dark traits

- The Light Triad — The counter-model

- Coherence Parasitism — The full geometry of how dark traits destabilize others' meaning

Psychopathy isn't binary. It's not monster vs normal. It's a spectrum of emotional and behavioral traits that vary continuously, express contextually, and predict outcomes ranging from incarceration to executive success.

Understanding the spectrum doesn't make you paranoid. It makes you precise. The person across from you isn't good or evil. They're a configuration of traits navigating incentive structures. Some configurations are dangerous. Some are adaptive. Some are both.

Once you see the dimensions clearly, you stop asking "Are they a psychopath?" and start asking: "How much Factor 1? How much Factor 2? What context? What does that predict?"

That's not cynicism. That's seeing the geometry clearly.

Series: Dark Personality Science | Part: 4 of 10

This is Part 4 of the Dark Personality Science series, exploring the psychology of traits that predict exploitation and harm. Next: "Narcissism Beyond the Selfie: Grandiose vs Vulnerable."

Further Reading

- Hare, R. D. (1993). Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us. Guilford Press.

- Skeem, J. L., Polaschek, D. L., Patrick, C. J., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2011). "Psychopathic personality: Bridging the gap between scientific evidence and public policy." Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(3), 95-162.

- Lilienfeld, S. O., Watts, A. L., Francis Smith, S., Berg, J. M., & Latzman, R. D. (2015). "Psychopathy deconstructed: A multivariate perspective on personality structure." Nature Reviews Psychology, 1, 63-76.

- Babiak, P., & Hare, R. D. (2006). Snakes in Suits: When Psychopaths Go to Work. HarperCollins.

- Dutton, K. (2012). The Wisdom of Psychopaths: What Saints, Spies, and Serial Killers Can Teach Us About Success. Scientific American / Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Patrick, C. J., Fowles, D. C., & Krueger, R. F. (2009). "Triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Developmental origins of disinhibition, boldness, and meanness." Development and Psychopathology, 21(3), 913-938.

- Mahmut, M. K., Homewood, J., & Stevenson, R. J. (2008). "The characteristics of non-criminals with high psychopathy traits: Are they similar to criminal psychopaths?" Journal of Research in Personality, 42(3), 679-692.

Comments ()