The Pythagorean Theorem: a² + b² = c² and Why It Matters

The Pythagorean theorem is not about triangles. It's about how distance works.

Here's what a² + b² = c² actually says: if you walk 3 blocks east and 4 blocks north, you're exactly 5 blocks from where you started — as the crow flies. Not 7 blocks (3+4). Not some complicated mess. Exactly 5, because 3² + 4² = 5².

This is the unlock: the Pythagorean theorem is the definition of distance in flat space. It tells you how to calculate "how far apart" when you can only measure horizontal and vertical.

Every time you use distance — in physics, in navigation, in computer graphics, in machine learning — you're using Pythagoras. It's not just a triangle fact. It's the formula for measurement itself.

The Statement

In any right triangle, the square of the hypotenuse equals the sum of the squares of the other two sides.

The hypotenuse is the side opposite the right angle — always the longest side. Call its length c.

The legs are the two sides that form the right angle. Call their lengths a and b.

Then: a² + b² = c²

Equivalently: c = √(a² + b²)

This gives you the hypotenuse from the legs, or either leg from the hypotenuse and the other leg.

Why Squares?

Why a² + b² instead of a + b? What's special about squaring?

The answer is area. Literally.

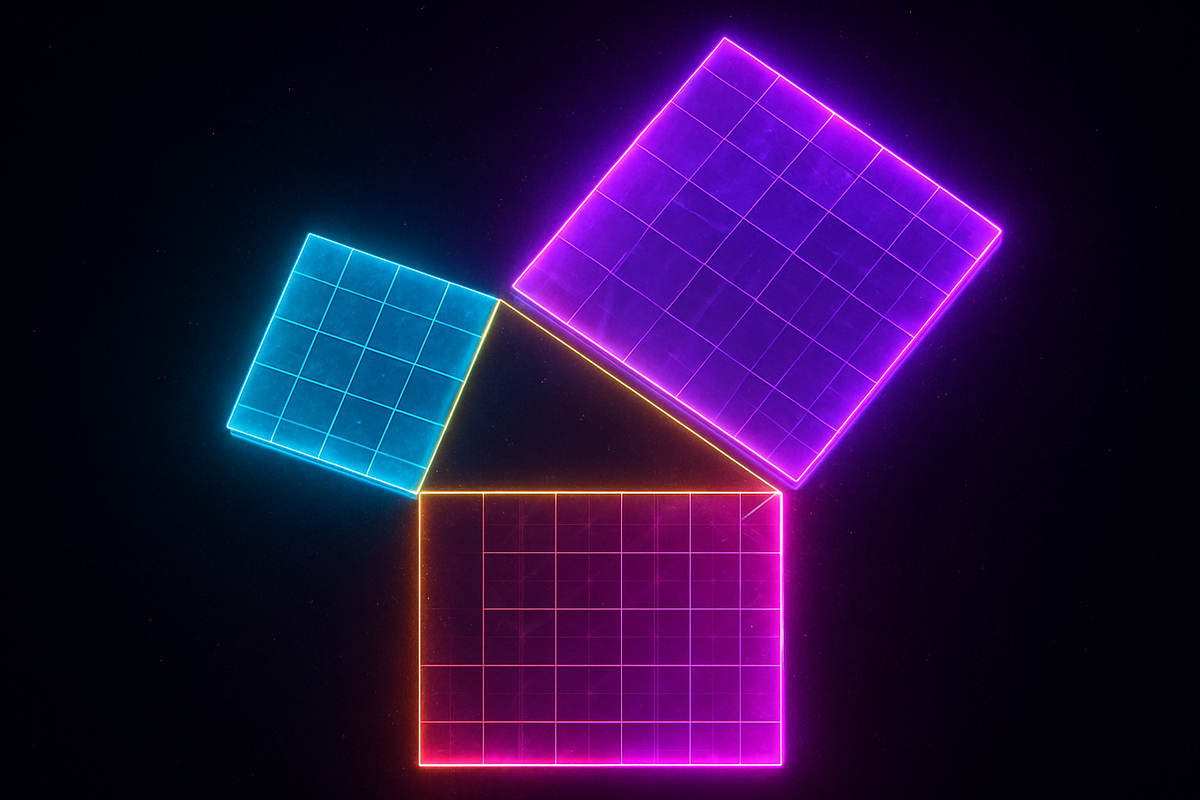

Draw a right triangle. Now draw a square on each side — a square whose edge is that side of the triangle. The area of the square on the hypotenuse equals the combined areas of the squares on the legs.

This is the original meaning. "The square on the hypotenuse" meant an actual geometric square. The theorem says those areas balance: the big square equals the two small squares combined.

Pythagoras proved it geometrically, by rearranging shapes. No algebra needed.

The Simplest Proof

Here's a proof that requires nothing but looking at a picture:

Take a square with side (a + b). Inside it, arrange four copies of your right triangle, corners pointing inward. They leave a square hole in the middle.

What's the area of the big square? (a + b)².

What's the total area of the four triangles? 4 × (½ab) = 2ab.

What's the area of the hole? Big square minus triangles = (a + b)² − 2ab = a² + 2ab + b² − 2ab = a² + b².

But the hole is a square with side c (the hypotenuse of each triangle). So its area is c².

Therefore: a² + b² = c².

Done. The theorem falls out from counting area two different ways.

The 3-4-5 Triangle

The most famous right triangle has legs 3 and 4, hypotenuse 5.

Check: 3² + 4² = 9 + 16 = 25 = 5². ✓

This was known to ancient builders. Need a perfect right angle? Cut a rope with knots at 3, 4, and 5 units. Stretch it into a triangle. The corner between the 3-side and the 4-side is exactly 90°.

Egyptian surveyors used this to lay out right angles for the pyramids. No protractors needed — just arithmetic and rope.

Pythagorean Triples

A Pythagorean triple is three whole numbers that satisfy a² + b² = c².

Besides 3-4-5, there's:

- 5-12-13

- 8-15-17

- 7-24-25

And infinitely more. Euclid found a formula that generates all of them.

Any triple can be scaled: 6-8-10 (double 3-4-5), 9-12-15 (triple it). These are all the same shape of triangle, just different sizes.

The existence of Pythagorean triples means there are right triangles with all-integer sides. This mattered to the Greeks, who were suspicious of irrational numbers. But most right triangles have irrational hypotenuses — like the 1-1-√2 triangle (a 45° right triangle).

Distance in Two Dimensions

Here's where the theorem becomes foundational.

Put a coordinate system on a plane. A point has coordinates (x, y). How far is it from the origin (0, 0)?

Draw a right triangle: horizontal leg from (0, 0) to (x, 0), vertical leg from (x, 0) to (x, y), hypotenuse from (0, 0) to (x, y).

The horizontal leg has length |x|. The vertical leg has length |y|. By Pythagoras, the hypotenuse — the actual distance — is √(x² + y²).

This is the Euclidean distance formula. It's Pythagoras applied.

Distance Between Any Two Points

Two points: (x₁, y₁) and (x₂, y₂). How far apart?

Same idea. Horizontal distance: |x₂ − x₁|. Vertical distance: |y₂ − y₁|.

Distance: √[(x₂ − x₁)² + (y₂ − y₁)²]

Every distance calculation you've ever done in a coordinate system — every one — is a disguised Pythagorean theorem.

Three Dimensions and Beyond

In 3D, the same logic extends. A point at (x, y, z) is distance √(x² + y² + z²) from the origin.

Between two points: √[(x₂−x₁)² + (y₂−y₁)² + (z₂−z₁)²]

In four dimensions: √(w² + x² + y² + z²).

In n dimensions: √(a₁² + a₂² + ... + aₙ²).

The Pythagorean theorem generalizes to any number of dimensions. It's not a 2D trick. It's the fundamental relationship between distance and components.

The Connection to Circles

Why is a circle all points at distance r from the center?

Because a point (x, y) is at distance √(x² + y²) from the origin. If that distance equals r, then:

√(x² + y²) = r

x² + y² = r²

This is the equation of a circle. It's Pythagoras, rearranged.

Every circle equation is the Pythagorean theorem saying "all these points are the same distance away."

What Happens When It's Not a Right Angle?

The Pythagorean theorem only works for right triangles. But there's a generalization:

Law of Cosines: c² = a² + b² − 2ab·cos(C)

Here, C is the angle opposite side c. If C = 90°, then cos(C) = 0, and you recover a² + b² = c².

For acute angles (C < 90°), cos(C) > 0, so c² < a² + b² — the side is shorter than Pythagoras would predict.

For obtuse angles (C > 90°), cos(C) < 0, so c² > a² + b² — the side is longer.

The Pythagorean theorem is a special case of the Law of Cosines, with the correction term zeroing out.

Non-Euclidean Geometry

The Pythagorean theorem fails in curved space.

On a sphere, the sum of squares of two sides of a "right triangle" is less than the square of the hypotenuse. The curvature squashes things together.

In hyperbolic space, the sum is greater than the square of the hypotenuse. The curvature pulls things apart.

The Pythagorean theorem is true in flat space and false in curved space. It's actually a test for flatness — if a² + b² = c² holds everywhere, your space is Euclidean.

Einstein's general relativity describes gravity as curved spacetime. The degree to which the Pythagorean theorem fails tells you the curvature — tells you the strength of gravity.

The Core Insight

a² + b² = c² isn't a formula to memorize. It's the definition of what "distance" means in flat space.

If you can move east-west and north-south independently, and you want to know the straight-line distance, you add squares of components and take the square root. That's what flat geometry is.

When you hear "Pythagorean theorem," don't think "right triangles." Think: this is how distance works. It's the most used formula in all of mathematics because distance is everywhere.

And it fits on a T-shirt.

Part 5 of the Geometry series.

Previous: Triangles: The Simplest Polygon and the Strongest Shape Next: Circles: The Shape of Constant Distance

Comments ()