Random Variables: Numbers That Depend on Chance

A coin flip isn't a number. But you can make it one.

Heads = 1, Tails = 0. Now you have a random variable.

This seemingly trivial assignment unlocks all of statistics. Once uncertain outcomes become numbers, you can add them, average them, graph them, compute expectations and variances, discover distributions, and prove limit theorems.

Random variables are the bridge from abstract probability to quantitative statistics.

What Random Variables Are

A random variable is a function that assigns a number to each outcome in a sample space.

Flip a coin: outcomes are {H, T}. Define X(H) = 1, X(T) = 0. Now X is a random variable.

Roll a die: outcomes are {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}. Let X be the number rolled. X is already a number, so the random variable is just the identity.

The randomness comes from the underlying experiment. The variable assigns numerical values to random outcomes.

Notation: Random variables are usually capital letters (X, Y, Z). Specific values are lowercase (x, y, z).

P(X = 3) means "the probability that X takes value 3."

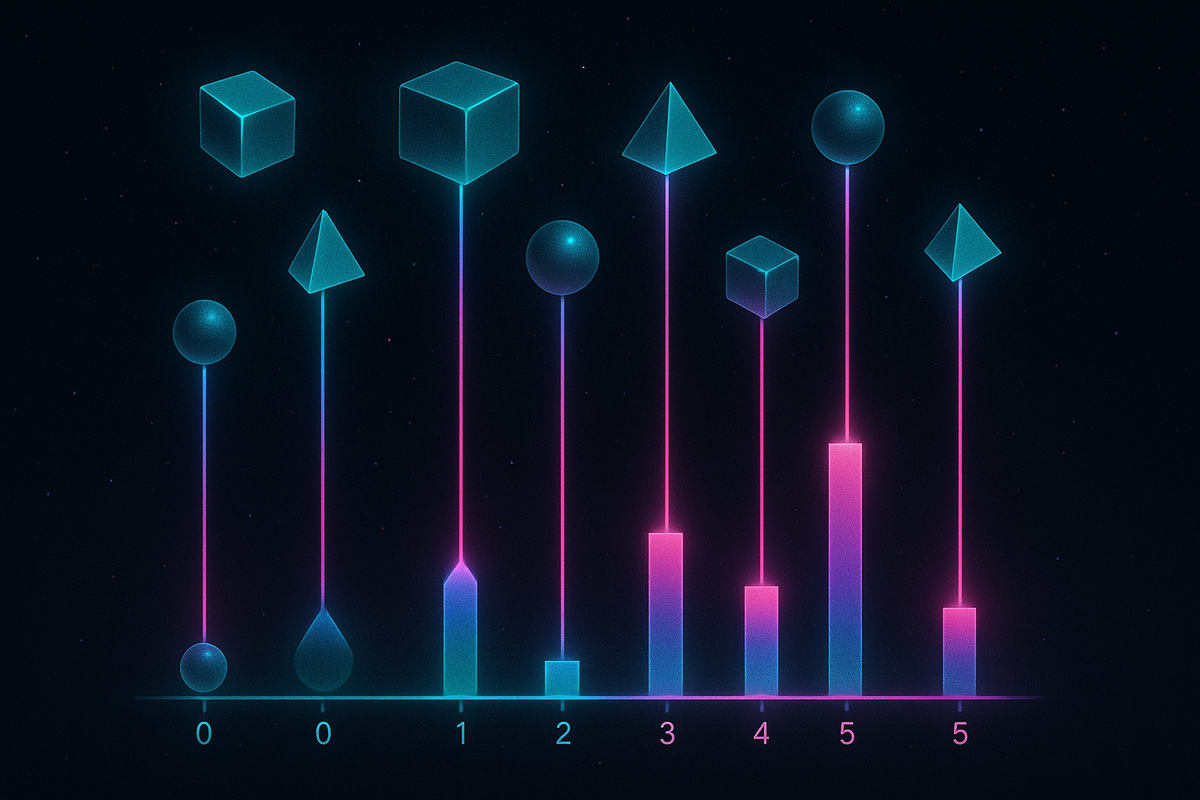

Discrete vs Continuous

Discrete random variables take countable values: integers, or a finite list.

Examples:

- Number of heads in 10 flips

- Number of customers arriving per hour

- Score on a test

Continuous random variables take values in an interval.

Examples:

- Height of a randomly selected person

- Time until a machine fails

- Temperature tomorrow

The distinction matters because continuous variables require calculus (integrals instead of sums), and P(X = exact value) = 0 for continuous variables—you measure probability of ranges instead.

Probability Mass Functions (Discrete)

For discrete random variables, the probability mass function (PMF) gives P(X = x) for each possible value x.

Example: Fair die.

P(X = 1) = P(X = 2) = ... = P(X = 6) = 1/6

Example: Number of heads in 2 flips.

X can be 0, 1, or 2.

P(X = 0) = P(TT) = 1/4 P(X = 1) = P(HT) + P(TH) = 2/4 = 1/2 P(X = 2) = P(HH) = 1/4

Requirements:

- Each probability ≥ 0

- Sum of all probabilities = 1

Probability Density Functions (Continuous)

For continuous random variables, the probability density function (PDF) is different.

P(a ≤ X ≤ b) = ∫ₐᵇ f(x) dx

The area under the curve between a and b gives probability of landing in that range.

Important: f(x) is not P(X = x). For continuous variables, P(X = exact value) = 0. The density can exceed 1; what matters is that the total area equals 1.

Example: Uniform distribution on [0, 1].

f(x) = 1 for x ∈ [0, 1], f(x) = 0 elsewhere.

P(0.25 ≤ X ≤ 0.75) = 0.75 - 0.25 = 0.5

Requirements:

- f(x) ≥ 0 everywhere

- Total area = ∫ f(x) dx = 1

Cumulative Distribution Functions

The cumulative distribution function (CDF) gives P(X ≤ x):

F(x) = P(X ≤ x)

For discrete variables: F(x) = Σ P(X = k) for all k ≤ x

For continuous variables: F(x) = ∫₋∞ˣ f(t) dt

Properties of CDFs:

- F(-∞) = 0

- F(∞) = 1

- F is non-decreasing

- P(a < X ≤ b) = F(b) - F(a)

The CDF contains all probability information. For continuous variables, f(x) = F'(x)—the PDF is the derivative of the CDF.

Multiple Random Variables

Often we have several random variables together.

Joint distribution: P(X = x and Y = y) or f(x, y) for continuous.

Marginal distribution: The distribution of one variable, ignoring the other. P(X = x) = Σᵧ P(X = x, Y = y)

Conditional distribution: The distribution of one variable given the other. P(Y = y | X = x) = P(X = x, Y = y) / P(X = x)

Independence: X and Y are independent if P(X = x, Y = y) = P(X = x) × P(Y = y) for all x, y.

Functions of Random Variables

If X is a random variable and g is a function, then Y = g(X) is also a random variable.

Example: X is die roll. Y = X².

Y takes values 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36 each with probability 1/6.

Example: X is uniform on [0, 1]. Y = -ln(X).

This transforms the uniform distribution into an exponential distribution. Such transformations are fundamental to simulation.

Why Random Variables Matter

Computation: Random variables let you calculate. You can add them (total of two dice), average them (sample mean), multiply them, compose them.

Generalization: The same math works for any random variable. The theory of expectations, variances, and distributions applies whether you're studying coin flips, stock prices, or quantum measurements.

Limit Theorems: The Law of Large Numbers and Central Limit Theorem are about random variables—they explain why averages converge and why the normal distribution appears everywhere.

Modeling: Real phenomena are modeled as random variables. Height, measurement error, arrival times, lifetimes—all become tractable through random variable formalism.

Notation and Conventions

P(X = x) or pₓ(x) — probability mass function f(x) or fₓ(x) — probability density function F(x) or Fₓ(x) — cumulative distribution function

E[X] — expected value (mean) Var(X) — variance σ² — variance notation σ — standard deviation

X ~ Distribution — "X follows Distribution" X ~ Binomial(n, p) — X has binomial distribution with parameters n and p

Building Intuition

Think of a random variable as a number you don't know yet, but you know the probability of each possible value.

Before rolling a die, X is uncertain. You know P(X = 1) = 1/6, etc. After rolling, X has a definite value.

The random variable captures your uncertainty about the value—not uncertainty about the function, but uncertainty from the underlying random experiment.

Random variables make probability computational. Instead of reasoning about events as abstract sets, you reason about numerical quantities with calculable properties.

The Transformation

Events to numbers. Qualitative to quantitative. Sets to functions.

Random variables are the conceptual leap that makes statistics possible. Once you can assign numbers to random outcomes, the entire machinery of mathematics applies—arithmetic, algebra, calculus, limits.

The next articles explore what you can do with this: expected values, variances, and the distributions that random variables follow.

This is Part 5 of the Probability series. Next: "Expected Value: The Average Outcome."

Part 5 of the Probability series.

Previous: Bayes' Theorem: Updating Beliefs with Evidence Next: Expected Value: The Long-Run Average

Comments ()