Recurrence Relations: Sequences Defined Recursively

The Fibonacci sequence: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34...

You've seen it. Maybe you know the rule: each number is the sum of the previous two.

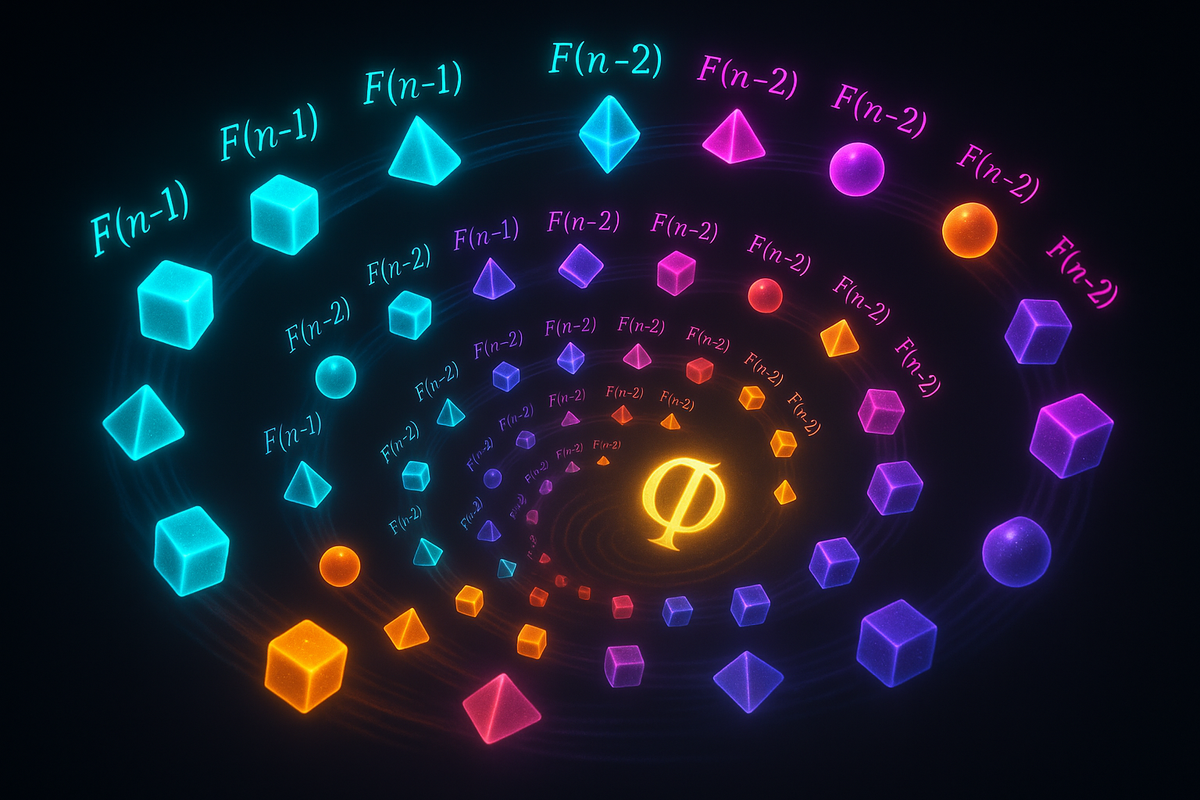

F(n) = F(n-1) + F(n-2)

This is a recurrence relation—a sequence defined in terms of itself. No explicit formula for the nth term. Instead, a recursive rule: to get the next value, look backward.

And it turns out this pattern—defining a sequence recursively—is everywhere:

- Algorithm runtime: T(n) = 2T(n/2) + n (merge sort's complexity)

- Population growth: P(t+1) = r × P(t) (exponential growth)

- Tower of Hanoi: H(n) = 2H(n-1) + 1 (moves required)

- Financial modeling: A(t+1) = A(t) × (1 + r) (compound interest)

- Physics: Newton's method, difference equations, discrete-time dynamics

Recurrence relations are the mathematics of feedback—where the present depends on the past. They're how we model processes that evolve step-by-step, where each state builds on the previous one.

The Definition

A recurrence relation defines a sequence where each term is a function of previous terms.

General form: a_n = f(a_{n-1}, a_{n-2}, ..., a_{n-k})

Plus initial conditions (base cases) to start the sequence.

Example: Fibonacci

- Recurrence: F(n) = F(n-1) + F(n-2)

- Initial conditions: F(0) = 0, F(1) = 1

Without initial conditions, the recurrence is undefined—you need starting points to generate the sequence.

Linear Recurrence Relations

The most common type: linear recurrence relations with constant coefficients.

Form: a_n = c_1 × a_{n-1} + c_2 × a_{n-2} + ... + c_k × a_{n-k}

Where c_1, c_2, ..., c_k are constants.

Examples:

- Geometric sequence: a_n = r × a_{n-1} (constant ratio)

- Arithmetic sequence: a_n = a_{n-1} + d (constant difference—technically a_n = 1 × a_{n-1} + d, inhomogeneous)

- Fibonacci: a_n = a_{n-1} + a_{n-2}

Linear recurrences have closed-form solutions—explicit formulas for a_n without recursion.

Solving Linear Recurrences: The Characteristic Equation

Consider: a_n = c_1 × a_{n-1} + c_2 × a_{n-2}

Guess: a_n = r^n for some constant r.

Substitute: r^n = c_1 × r^{n-1} + c_2 × r^{n-2}

Divide by r^{n-2}: r² = c_1 × r + c_2

Rearrange: r² - c_1 × r - c_2 = 0

This is the characteristic equation. Solve for r using the quadratic formula.

Two distinct roots r_1, r_2: General solution is a_n = A × r_1^n + B × r_2^n, where A and B are determined by initial conditions.

Example: Fibonacci F(n) = F(n-1) + F(n-2)

Characteristic equation: r² - r - 1 = 0

Solutions: r = (1 ± √5) / 2

Let φ = (1 + √5) / 2 (golden ratio ≈ 1.618) and ψ = (1 - √5) / 2 ≈ -0.618

General solution: F(n) = A × φ^n + B × ψ^n

Apply initial conditions F(0) = 0, F(1) = 1:

- A + B = 0

- A × φ + B × ψ = 1

Solve: A = 1/√5, B = -1/√5

Closed-form: F(n) = (φ^n - ψ^n) / √5

This is Binet's formula. The Fibonacci sequence—defined recursively—has an explicit formula involving irrational numbers and exponents. Mind-blowing.

When Roots Are Equal

If the characteristic equation has a repeated root r, the solution changes:

a_n = (A + B × n) × r^n

Example: a_n = 2a_{n-1} - a_{n-2}

Characteristic equation: r² - 2r + 1 = 0 → (r - 1)² = 0 → r = 1 (repeated)

Solution: a_n = A + B × n (linear function)

This models sequences growing linearly rather than exponentially.

Inhomogeneous Recurrence Relations

What if there's a non-recursive term?

a_n = c_1 × a_{n-1} + c_2 × a_{n-2} + f(n)

Example: a_n = a_{n-1} + n (each term increases by n)

Solution approach:

- Solve the homogeneous part (set f(n) = 0): a_n^(h) = c_1 × a_{n-1} + c_2 × a_{n-2}

- Find a particular solution a_n^(p) that satisfies the full equation

- General solution: a_n = a_n^(h) + a_n^(p)

Example continued: Homogeneous: a_n = a_{n-1} → a_n^(h) = A (constant) Particular: Guess a_n^(p) = Bn + C. Substitute, solve for B and C. Result: a_n = A + Bn + C

Initial conditions determine A.

Divide-and-Conquer Recurrences

Algorithm analysis often yields divide-and-conquer recurrences:

T(n) = a × T(n/b) + f(n)

Where:

- a = number of subproblems

- b = factor by which problem size shrinks

- f(n) = cost of dividing and combining

Examples:

- Binary search: T(n) = T(n/2) + O(1) → O(log n)

- Merge sort: T(n) = 2T(n/2) + O(n) → O(n log n)

- Karatsuba multiplication: T(n) = 3T(n/2) + O(n) → O(n^{log₂3}) ≈ O(n^{1.58})

These are solved using the Master Theorem.

The Master Theorem

For T(n) = a × T(n/b) + f(n) where f(n) = O(n^d):

Case 1: If a > b^d, then T(n) = Θ(n^{log_b a}) Case 2: If a = b^d, then T(n) = Θ(n^d log n) Case 3: If a < b^d, then T(n) = Θ(n^d)

Intuition:

- Case 1: Recursion dominates → runtime determined by number of subproblems

- Case 2: Recursion and combining balanced → extra log factor

- Case 3: Combining dominates → runtime determined by f(n)

Example: Merge sort T(n) = 2T(n/2) + O(n)

- a = 2, b = 2, d = 1

- a = b^d (2 = 2¹)

- Case 2: T(n) = Θ(n log n)

The Master Theorem transforms recursive runtime analysis into pattern matching.

The Tower of Hanoi

Three pegs. n disks of increasing size. Goal: move all disks from peg A to peg C using peg B, never placing larger disk on smaller.

Recurrence: H(n) = 2H(n-1) + 1

Why? To move n disks:

- Move top n-1 disks from A to B (using C): H(n-1) moves

- Move largest disk from A to C: 1 move

- Move n-1 disks from B to C (using A): H(n-1) moves

Total: 2H(n-1) + 1

Initial condition: H(1) = 1 (move single disk)

Solve: H(n) = 2H(n-1) + 1 Expand: H(n) = 2(2H(n-2) + 1) + 1 = 4H(n-2) + 2 + 1 Continue: H(n) = 2^k H(n-k) + (2^k - 1)

Set k = n-1: H(n) = 2^{n-1} × H(1) + (2^{n-1} - 1) = 2^{n-1} + 2^{n-1} - 1 = 2^n - 1

Closed-form: H(n) = 2^n - 1

For 64 disks (the legend of Hanoi), 2^{64} - 1 ≈ 1.8 × 10^{19} moves. At one move per second, that's 585 billion years—longer than the age of the universe.

Recurrence relations reveal exponential growth hiding in simple rules.

Generating Functions: Solving Recurrences with Algebra

Generating function: Encode a sequence a_0, a_1, a_2, ... as a power series:

G(x) = a_0 + a_1 × x + a_2 × x² + a_3 × x³ + ...

Why? Recurrence relations on sequences become algebraic equations on generating functions.

Example: Fibonacci F(n) = F(n-1) + F(n-2), F(0) = 0, F(1) = 1

Let G(x) = Σ F(n) × x^n

Multiply recurrence by x^n, sum over n: Σ F(n) × x^n = Σ F(n-1) × x^n + Σ F(n-2) × x^n

Simplify using generating function algebra: G(x) = x × G(x) + x² × G(x) + x

Solve for G(x): G(x) = x / (1 - x - x²)

Partial fraction decomposition: G(x) = (1/√5) × [1/(1 - φx) - 1/(1 - ψx)]

Expand as power series (geometric series): G(x) = (1/√5) × Σ (φ^n - ψ^n) × x^n

Coefficient of x^n: F(n) = (φ^n - ψ^n) / √5

We derived Binet's formula via generating functions. This technique works for many recurrences.

Catalan Numbers (Again)

Catalan numbers satisfy a recurrence:

C_n = Σ_{i=0}^{n-1} C_i × C_{n-1-i}

With C_0 = 1.

Why? Counting binary trees: A tree with n nodes has a root. The left subtree has i nodes (C_i ways), right subtree has n-1-i nodes (C_{n-1-i} ways). Sum over all splits.

This recurrence can be solved via generating functions to get the closed-form:

C_n = (1/(n+1)) × C(2n, n)

Recurrence relations reveal structure in combinatorial sequences.

Population Models

Exponential growth: P(t+1) = r × P(t)

Solution: P(t) = P(0) × r^t

If r > 1, exponential growth. If r < 1, exponential decay.

Logistic growth: P(t+1) = r × P(t) × (1 - P(t) / K)

Where K = carrying capacity. This models populations with resource constraints. Non-linear recurrence—exhibits complex dynamics (chaos for certain r values).

Fibonacci rabbits: Fibonacci's original problem—pairs of rabbits breeding. Each pair produces a new pair every month, starting at age 1 month. F(n) = breeding pairs at month n.

Recurrence relations model biological and economic systems where state evolves step-by-step.

Difference Equations: Continuous Analogue

Recurrence relations are discrete-time difference equations.

Continuous analogue: differential equations.

Connection: As time step shrinks, difference equations approximate differential equations.

Example: a_n = a_{n-1} + r × Δt → da/dt = r (exponential growth)

Discrete and continuous math mirror each other. Recurrence relations are the discrete version of differential equations—both model systems evolving over time.

Recurrence in Algorithm Analysis

Every recursive algorithm yields a recurrence relation.

Binary search: T(n) = T(n/2) + O(1) → O(log n)

Merge sort: T(n) = 2T(n/2) + O(n) → O(n log n)

Quick sort (average case): T(n) = 2T(n/2) + O(n) → O(n log n)

Matrix multiplication (Strassen): T(n) = 7T(n/2) + O(n²) → O(n^{log₂7}) ≈ O(n^{2.807})

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT): T(n) = 2T(n/2) + O(n) → O(n log n)

Analyzing algorithms = solving recurrence relations. The Master Theorem, substitution method, and generating functions are tools for extracting closed-forms.

Recurrence in Sequences You Know

Powers of 2: a_n = 2 × a_{n-1}, a_0 = 1 → a_n = 2^n

Factorials: a_n = n × a_{n-1}, a_1 = 1 → a_n = n!

Triangular numbers: a_n = a_{n-1} + n, a_0 = 0 → a_n = n(n+1)/2

Harmonic numbers: H_n = H_{n-1} + 1/n, H_1 = 1 → H_n = 1 + 1/2 + 1/3 + ... + 1/n ≈ ln(n)

Catalan numbers: C_n = Σ C_i × C_{n-1-i} → C_n = C(2n, n) / (n+1)

Recurrence relations unify seemingly unrelated sequences under a common framework.

Linear Homogeneous Recurrences: Higher Orders

For k-th order recurrence: a_n = c_1 × a_{n-1} + c_2 × a_{n-2} + ... + c_k × a_{n-k}

Characteristic equation: r^k - c_1 × r^{k-1} - c_2 × r^{k-2} - ... - c_k = 0

Solve for k roots. General solution is linear combination: a_n = A_1 × r_1^n + A_2 × r_2^n + ... + A_k × r_k^n

Example: a_n = a_{n-1} + a_{n-2} + a_{n-3} (Tribonacci)

Characteristic equation: r³ - r² - r - 1 = 0

Solve numerically for roots, construct solution.

Higher-order recurrences model more complex dependencies—systems where the present depends on multiple past states.

Matrix Methods for Recurrence Relations

Recurrence relations can be represented as matrix equations.

Example: Fibonacci [F(n) ] = [1 1] × [F(n-1)] [F(n-1)] [1 0] [F(n-2)]

Let M = [1 1] [1 0]

Then [F(n) ] = M^{n-1} × [F(1)] [F(n-1)] [F(0)]

F(n) = (M^{n-1})_{1,1}

Matrix exponentiation computes F(n) in O(log n) time (via repeated squaring). Faster than naive recursion (O(φ^n)) or iteration (O(n)).

This technique generalizes: any linear recurrence can be written as matrix multiplication.

Why Recurrence Relations Matter

Recurrence relations are how we model feedback loops—systems where the present depends on the past.

- Algorithms: Runtime analysis reduces to recurrences

- Biology: Population dynamics, epidemic spread

- Economics: Compound interest, investment growth

- Physics: Discrete-time dynamics, difference equations

- Combinatorics: Counting sequences (Fibonacci, Catalan, etc.)

They're the discrete analogue of differential equations—the mathematics of change over discrete steps.

And they reveal something profound: simple rules generate complex behavior. The Fibonacci sequence—defined by two numbers and one addition rule—produces the golden ratio, appears in nature (pinecones, sunflowers), and connects to deep mathematical structures.

Recurrence relations show that complexity emerges from simplicity, given enough iterations.

Further Reading

- Graham, Ronald L., Donald E. Knuth, and Oren Patashnik. Concrete Mathematics. Addison-Wesley, 2nd edition, 1994. (Chapter 7: Generating Functions)

- Rosen, Kenneth H. Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications. McGraw-Hill, 8th edition, 2018. (Recurrence relations, solving techniques)

- Cormen, Thomas H., et al. Introduction to Algorithms. MIT Press, 4th edition, 2022. (Master Theorem, algorithm analysis)

- Wilf, Herbert S. Generatingfunctionology. A K Peters, 3rd edition, 2005. (Generating functions for recurrences)

This is Part 8 of the Discrete Mathematics series, exploring the foundational math of computer science, algorithms, and computational thinking. Next: "Big O Notation Explained — How Algorithms Scale."

Part 8 of the Discrete Mathematics series.

Previous: Trees: Connected Graphs Without Cycles Next: Big O Notation: How Algorithms Scale

Comments ()