RNA Interference: Silencing Genes on Demand

In 1998, two scientists published a paper that would win them a Nobel Prize and launch an entire industry. Andrew Fire and Craig Mello had been studying gene expression in C. elegans—the tiny nematode worm that molecular biologists love because it's transparent, genetically tractable, and dies quickly.

They were trying to silence genes using RNA. The obvious approach—injecting antisense RNA, the reverse complement of a target mRNA—worked, but weakly. Single-stranded RNA wasn't very effective.

Then they tried something different. They injected double-stranded RNA.

The effect was dramatic. Gene silencing was ten times more potent than with single-stranded RNA. More remarkably, the silencing spread. Inject double-stranded RNA into one part of the worm, and the silencing effect shows up throughout the organism. A tiny amount of RNA could shut down a gene completely, persistently, and with exquisite specificity.

Fire and Mello called it RNA interference—RNAi. They didn't know it at the time, but they'd discovered an ancient immune system, one that cells have been using to defend against viruses and regulate their own genes for billions of years.

We could now silence any gene we wanted, on demand. Genetic research would never be the same.

How It Works

Let's trace the mechanism. It's elegant, evolved, and now hijackable.

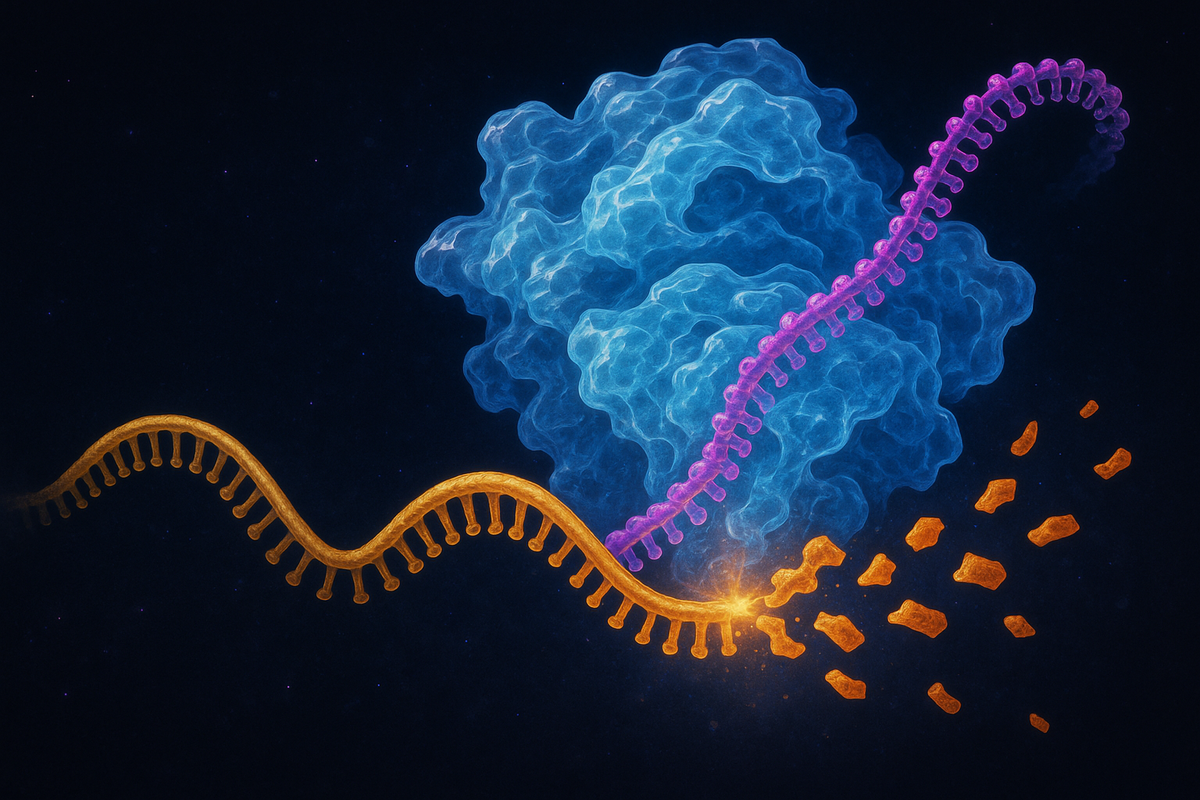

When double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) appears in a cell, an enzyme called Dicer recognizes it. Dicer is a molecular scissors—it cuts the long dsRNA into short fragments about 21-23 nucleotides long. These fragments are called small interfering RNAs, or siRNAs.

The siRNAs get loaded into a protein complex called RISC (RNA-Induced Silencing Complex). RISC keeps one strand of the siRNA—the guide strand—and discards the other. The guide strand then acts as a targeting system, directing RISC to any mRNA with a complementary sequence.

When RISC finds a matching mRNA, it cleaves it. The mRNA is destroyed. The gene is silenced.

The beauty of the system: the silencing is catalytic. One siRNA molecule, loaded into RISC, can destroy multiple target mRNAs. The guide strand isn't consumed—it just keeps matching and cleaving, matching and cleaving.

Twenty-one nucleotides of RNA can shut down a gene permanently. Point, shoot, silence.

Why It Exists

Why would cells have this machinery? What problem does it solve?

The original function, almost certainly, was defense. Viruses with RNA genomes produce double-stranded RNA intermediates during replication. This is unusual—cells don't normally make dsRNA in significant quantities. So dsRNA became a signal meaning "virus present."

The Dicer-RISC pathway lets cells recognize that signal and respond by destroying the viral RNA. It's an immune system—not the antibody-based adaptive immunity that vertebrates have, but a more ancient, RNA-based defense that exists in plants, fungi, invertebrates, and many other organisms.

But evolution is opportunistic. If you have a pathway for destroying specific RNA sequences, you can repurpose it for regulation. And cells did.

MicroRNAs are endogenous—the cell makes them on purpose, from its own genome. They use the same RISC machinery but for gene regulation rather than defense. Instead of destroying viral RNA, microRNAs fine-tune the cell's own gene expression.

This is the pattern: defense mechanisms get co-opted for regulation. The innate immune response became a control system. The sword became a scalpel.

The Research Revolution

For scientists studying gene function, RNAi was transformative.

Before RNAi, figuring out what a gene does typically meant knocking it out entirely—deleting it from the genome. This required breeding strategies that could take years, especially in mammals. Gene knockouts were heroic projects, each one a major undertaking.

RNAi offered a shortcut. Synthesize an siRNA targeting your gene of interest. Introduce it into cells or organisms. Wait a few days. The gene is silenced—not deleted, but functionally turned off. Now you can study what happens when that gene is missing.

This is reverse genetics: starting from the gene and asking what it does, rather than starting from a phenotype and finding the gene. RNAi made reverse genetics fast and accessible.

Within a few years of Fire and Mello's discovery, researchers were conducting genome-wide RNAi screens—systematically silencing every gene in an organism and cataloging the effects. In C. elegans, in Drosophila, eventually in mammalian cell lines, scientists worked through the genome one gene at a time. What happens when you silence this one? What about that one?

The flood of data was enormous. Functions were assigned to thousands of genes. Pathways were mapped. The architecture of cellular life came into sharper focus.

RNAi gave biology a universal gene silencing tool. The obscure became tractable.

The Jump to Therapeutics

If you can silence any gene, you can potentially treat any disease caused by too much of something.

That's the therapeutic logic. Some diseases result from genes being overexpressed or making toxic products. If you could deliver siRNAs that silence those genes, you could, in principle, treat the disease at its source.

The first attempts in the early 2000s were disappointing. siRNAs triggered immune responses, got degraded in the bloodstream, and couldn't get into target cells efficiently. The same problems that plagued mRNA therapeutics plagued RNAi: delivery, stability, immunogenicity.

Sound familiar? The same solutions emerged. Chemical modifications to the RNA backbone increased stability and reduced immune activation. Lipid nanoparticles protected the siRNAs during transit and delivered them into cells.

In 2018, the FDA approved the first RNAi drug: patisiran, marketed as Onpattro. It treats hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis, a rare genetic disease where the liver produces a misfolded protein that accumulates in nerves and organs, eventually killing the patient.

Patisiran silences the gene encoding transthyretin. Less mRNA, less protein, less accumulation, slower disease progression. The siRNA is delivered in lipid nanoparticles, injected intravenously every three weeks.

The drug works. Patients have improved neurological function and quality of life. A disease that was previously untreatable—and often fatal within a decade of diagnosis—became manageable.

From worm experiments in 1998 to FDA-approved medicine in 2018. Twenty years from discovery to treatment.

Alnylam and the Therapeutic Pipeline

The company behind patisiran is Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, which has bet everything on RNAi therapeutics. Founded in 2002, the company spent over a decade developing delivery technology and advancing candidates through clinical trials.

Since patisiran, Alnylam has won FDA approval for several more RNAi drugs:

Givosiran (Givlaari) for acute hepatic porphyria—a rare metabolic disorder that causes severe abdominal pain and neurological symptoms.

Lumasiran (Oxlumo) for primary hyperoxaluria type 1—a condition where the liver produces too much oxalate, leading to kidney stones and kidney failure.

Inclisiran (Leqvio) for hypercholesterolemia—high LDL cholesterol. This one isn't rare at all. It silences a gene called PCSK9, which regulates cholesterol levels. One injection every six months can significantly reduce LDL.

That last one matters. Most RNAi drugs have targeted rare diseases, in part because rare diseases have clearer regulatory paths and less competition. But inclisiran targets a huge market. Tens of millions of people have high cholesterol. If twice-yearly injections can control it better than daily pills, the therapeutic and commercial implications are enormous.

The pipeline is expanding. Alnylam and other companies have RNAi programs targeting Alzheimer's disease, hepatitis B, cardiovascular disease, and various cancers. The platform is proving versatile.

The first drug proved the concept. The pipeline proves the generality.

Antisense Oligonucleotides: The Cousin Technology

While we're here, let's talk about antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs)—a related technology that often gets discussed alongside RNAi.

ASOs are short, single-stranded pieces of synthetic DNA or chemically modified RNA. They bind to target mRNAs through Watson-Crick base pairing—the same A-T, G-C complementarity that holds DNA strands together.

Different ASO designs do different things:

RNase H-recruiting ASOs form DNA-RNA hybrids that get recognized and destroyed by a cellular enzyme called RNase H. The outcome is similar to siRNA: the target mRNA is degraded, the gene is silenced.

Splice-modifying ASOs don't destroy mRNA—they redirect how it's processed. By binding near splice sites, they can cause exons to be skipped or included, altering the protein product.

The most dramatic example: nusinersen (Spinraza), an ASO for spinal muscular atrophy. SMA is caused by mutations in a gene called SMN1. Patients have a backup gene, SMN2, but it's spliced incorrectly and produces mostly nonfunctional protein. Nusinersen binds to SMN2 mRNA and changes its splicing, causing it to produce functional SMN protein.

Before nusinersen, severe SMA was a death sentence—most patients died before age two. With treatment, many are walking, talking, going to school. The transformation in outcomes has been extraordinary.

ASOs aren't RNAi, but they're part of the same family: RNA-targeting therapeutics that intervene at the level of gene expression rather than protein function. The distinction between the technologies matters for researchers; for patients, what matters is that genetic diseases are becoming treatable.

Delivery Is Still the Bottleneck

Twenty years into the RNAi therapeutic era, the hardest problem remains delivery.

The liver is easy. Lipid nanoparticles and conjugation strategies reliably get RNA into hepatocytes. That's why most approved RNAi drugs target liver-expressed genes—the organ is accessible, and drug delivery is solved.

Everywhere else is harder.

The brain is protected by the blood-brain barrier. Getting RNA therapeutics into neurons is a major challenge, limiting applications in neurodegenerative disease.

Muscle is distributed throughout the body, making systemic delivery necessary. Achieving sufficient concentration in muscle cells remains difficult.

Tumors are heterogeneous and often poorly vascularized. Delivering siRNAs to all cancer cells, not just those near blood vessels, is unsolved.

Immune cells are promising targets for cancer immunotherapy but hard to transfect efficiently in vivo.

The field is advancing. Conjugate technologies—attaching siRNAs to molecules that target specific cell types—are expanding the addressable tissue range. GalNAc conjugation, which directs RNA to hepatocytes, is the first success story; similar approaches for other organs are in development.

But delivery remains the limiting factor. The biology works. The pharmaceutical engineering is catching up.

CRISPR's Shadow

In 2012, as RNAi therapeutics were grinding through clinical development, CRISPR-Cas9 emerged. Another revolution. Another tool for manipulating genes.

CRISPR and RNAi are often compared—both allow targeting of specific genes, both transformed research, both have therapeutic potential. But they do fundamentally different things.

RNAi silences genes temporarily. The effect requires ongoing presence of the siRNA. Stop treatment, and gene expression returns. This can be an advantage (the therapy is reversible) or a limitation (chronic dosing is required).

CRISPR edits genes permanently. Cut the DNA, repair it wrong, and the change persists in all daughter cells. One treatment, lifetime effect. This is an advantage (no chronic dosing) or a limitation (no undo button).

The technologies are complementary, not competitive. RNAi is appropriate when you want to reduce gene expression without permanent changes—cancer genes, inflammatory genes, genes where you might want to restore expression later. CRISPR is appropriate when permanent modification is acceptable or desirable—genetic diseases caused by single mutations, for example.

Both have a place. The molecular toolkit expands.

What We Can Now Do

Let's step back and appreciate what Fire and Mello's discovery enabled.

Before RNAi, silencing a specific gene in a living organism was a multi-year project requiring specialized techniques. Now it takes days.

Before RNAi, treating diseases caused by toxic gene products meant trying to neutralize the protein or manage symptoms. Now we can prevent the protein from being made in the first place.

Before RNAi, we didn't understand that cells use small RNAs for their own gene regulation. Now we know microRNAs regulate more than half of human genes.

RNAi revealed a whole layer of biology we'd missed, and then gave us tools to manipulate it.

The 2006 Nobel Prize citation called RNA interference "a fundamental mechanism for controlling the flow of genetic information." That's correct, but understated. RNAi is also a pharmaceutical platform, a research method, and a window into how cells defend themselves and regulate their own expression.

Fire and Mello found something elegant hiding in plain sight. The implications are still unfolding.

Further Reading

- Fire, A., Xu, S., Montgomery, M. K., Kostas, S. A., Driver, S. E., & Mello, C. C. (1998). "Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans." Nature. - Setten, R. L., Rossi, J. J., & Han, S. (2019). "The current state and future directions of RNAi-based therapeutics." Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. - Adams, D., et al. (2018). "Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic, for Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis." New England Journal of Medicine. - Crooke, S. T. (2017). "Molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides." Nucleic Acid Therapeutics.

This is Part 4 of the RNA Renaissance series. Next: "Long Non-Coding RNA: The Dark Matter of the Genome."

Comments ()