Selection as Constructor: Where Assembly Theory Meets Constructor Theory

Selection as Constructor: Where Assembly Theory Meets Constructor Theory

Series: Assembly Theory | Part: 5 of 9

There's a puzzle at the heart of complexity science: How do you explain the existence of things that seem impossible to make by chance alone? A bacterium. A Boeing 747. A Beethoven sonata. The standard answer invokes selection—Darwin's elegant mechanism that explains how complexity emerges through differential survival and reproduction.

But here's the deeper question: What, exactly, is selection? Is it just a filter that sieves through random variation? Or is it something more fundamental—a physical principle as real as gravity or thermodynamics?

This is where two radical frameworks converge. Assembly Theory (developed by Lee Cronin and Sara Walker) measures complexity by counting the minimum steps needed to construct an object. Constructor Theory (developed by David Deutsch and Chiara Marletto) describes physical laws in terms of which transformations are possible and which aren't. When you bring them together, something striking emerges: selection isn't just a biological quirk. It's a constructor—a physical system that enables transformations that wouldn't otherwise occur.

This article explores that convergence. We'll see how selection processes act as constructors that make complex assembly not just possible but inevitable. We'll understand why life isn't a lucky accident but a consequence of constructor-theoretic principles operating at the molecular scale. And we'll glimpse how this framework might extend beyond biology to explain the emergence of meaning, culture, and consciousness.

Constructor Theory in Five Minutes

Constructor Theory is a radically different way of formulating physical laws. Instead of describing what happens (trajectories, states, probabilities), it describes what tasks are possible.

A constructor is a physical system that causes a specific transformation to occur and then remains unchanged to perform that transformation again. Think of an enzyme catalyzing a reaction, a ribosome assembling proteins, or a 3D printer manufacturing parts. The constructor enables a transformation without being consumed by it.

A task is a set of input-output pairs. For example:

- "Convert substrate A into product B"

- "Copy information from DNA to RNA"

- "Translate symbolic instructions into protein sequences"

Constructor Theory asks: Which tasks are possible in principle? Which are impossible? And crucially: What properties must a physical system have to be a constructor for a given task?

This shift from dynamical laws to task-theoretic principles is profound. Traditional physics says: "Here's the Hamiltonian; evolve the system forward." Constructor Theory says: "Here are the possible and impossible transformations; now explain which physical systems can perform them."

The payoff? Constructor Theory naturally captures counterfactual properties—what could happen under different conditions. This makes it the right framework for understanding information, knowledge, and causation in a way that standard physics struggles with.

David Deutsch puts it bluntly: "Laws of physics should be expressed as statements about which transformations are possible and which are impossible." Once you see the world this way, selection processes start looking very different.

Assembly Theory: Counting Steps to Complexity

Assembly Theory, as we've explored in previous articles in this series, provides a rigorous way to measure molecular complexity. The assembly index of an object is the minimum number of joining operations needed to construct it from elementary building blocks.

A simple molecule like methane (CH₄) has an assembly index of 1—you can make it in a single joining step. A moderately complex molecule like glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆) has an assembly index around 6-7. A protein with 200 amino acids might have an assembly index in the hundreds.

The key insight: High assembly index molecules don't appear by chance. The probability of randomly assembling a molecule with an assembly index of 15 or higher is so astronomically low that if you detect such a molecule, you can infer that a selection process produced it.

This gives us an operational definition of life: Life is the process that generates molecular ensembles with high assembly index and high copy number. Not metabolism, not reproduction, not homeostasis—those are mechanisms. The signature is molecular complexity that couldn't arise by chance.

But here's where things get interesting. Assembly Theory describes what selection produces (high-AI molecules). Constructor Theory describes how physical systems enable transformations. When you combine them, you get a framework for understanding selection itself as a physical process.

Selection as Physical Causation

Let's start with a deceptively simple question: What does natural selection actually do?

The standard answer: It filters variation. Organisms with beneficial traits survive and reproduce more than those without. Over generations, beneficial traits accumulate. Selection is the sieve; variation is the raw material.

But this framing misses something crucial. Selection doesn't just filter existing possibilities—it creates new causal pathways that wouldn't otherwise exist.

Consider a population of RNA molecules undergoing replication with error. Most mutations are neutral or deleterious. But occasionally, a mutation produces an RNA sequence that can catalyze its own replication more efficiently. This sequence will increase in frequency.

From a constructor-theoretic perspective, what just happened? A new constructor emerged: a self-replicating RNA molecule that can perform the task of making copies of itself more reliably than competitors. This constructor enables a transformation (RNA → 2× RNA) that was physically possible but extremely unlikely before selection acted.

Selection didn't just filter pre-existing molecules. It created a new constructor—a physical system capable of performing a specific task repeatably. That constructor, in turn, enables the production of other constructors (more complex catalysts, eventually proteins, eventually cells).

This is the deep link: Selection processes are themselves constructors whose task is to produce other constructors.

The Constructor Theory of Evolution

Chiara Marletto and David Deutsch have developed a constructor-theoretic formulation of evolution that makes this explicit. In their framework:

A Darwinian replicator is a constructor whose task is to copy information faithfully enough that variants can be selected but inaccurately enough that new information can emerge.

Let's unpack that:

- Replication is a task: Convert [information state A] into [two instances of information state A].

- A replicator is a constructor: It performs this task repeatedly without being consumed.

- Variation introduces new tasks: Errors in copying create variants, each defining a new replication task.

- Selection winnows constructors: Variants that perform the replication task more effectively (faster, more accurately, in more environments) outcompete others.

The result? An evolutionary process that can be understood purely in terms of which constructors for which tasks are possible, and which combinations of constructors enable new tasks.

This reframes the origin of life. Instead of asking "What is the probability of assembling a self-replicating molecule by chance?" we ask: "What constructors enable the task of self-replication, and what physical conditions allow those constructors to emerge?"

Assembly Theory answers the second question: You need an environment where molecules with sufficiently high assembly index can be produced and then selected for functionality. Not randomly—by iterative construction guided by selection acting as a constructor-generating process.

Assembly Space as Constructor Space

Here's where Assembly Theory and Constructor Theory become deeply complementary.

Assembly space is the set of all possible assembly pathways—the combinatorial graph of how elementary parts can be joined into complex objects. Each node in this graph is a possible object; each edge is a joining operation.

Constructor space is the set of all possible constructors—the physical systems capable of performing specific tasks.

These spaces are intimately related. Every high-AI object in assembly space corresponds to a specific assembly pathway—a sequence of joining operations. To traverse that pathway physically, you need constructors that can perform each operation.

For simple molecules, the environment itself provides constructors: thermal energy, catalytic surfaces, photochemistry. But as assembly index increases, the probability of random environmental constructors performing the needed operations drops exponentially.

This is the constructor bottleneck: Beyond a certain assembly index (around AI = 15), you need evolved constructors—physical systems specifically structured to perform the complex assembly tasks required.

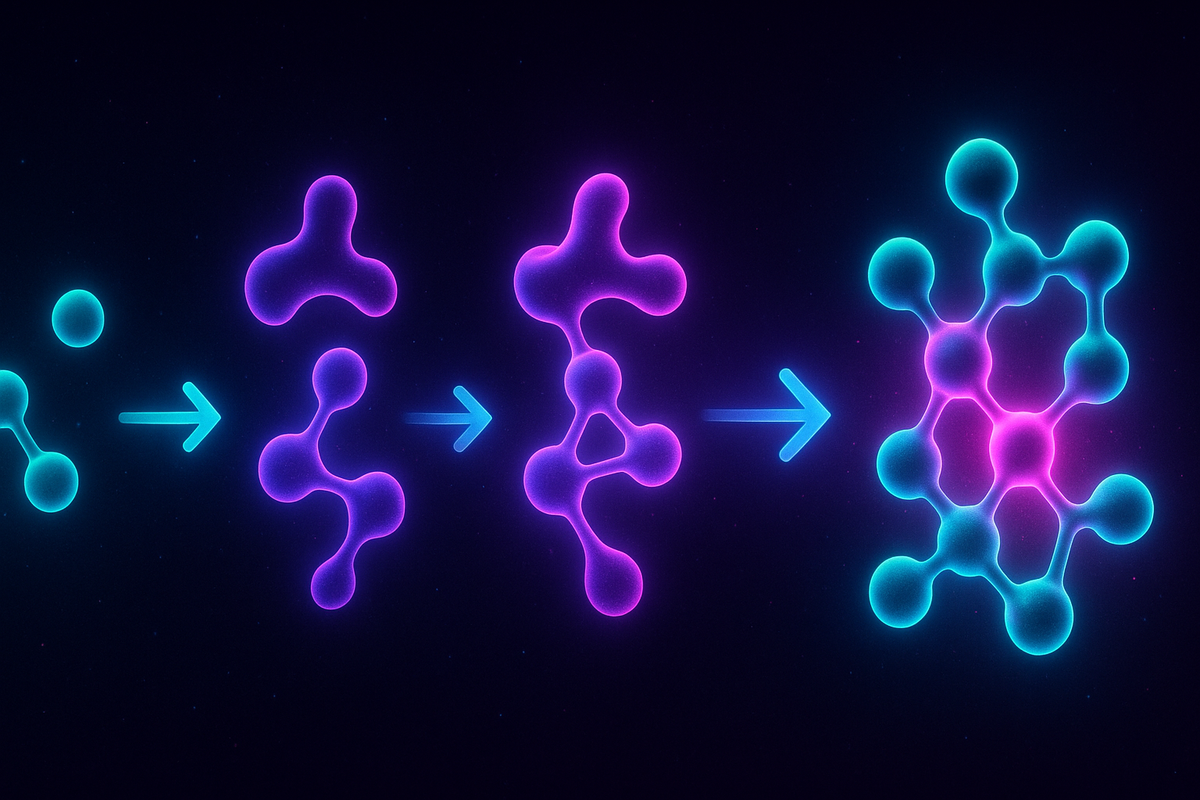

Selection solves the constructor bottleneck by iteratively building constructors for more complex assembly tasks:

- Simple constructors (ribozymes, autocatalytic networks) emerge by chance in favorable chemical environments.

- These enable the assembly of moderately complex molecules.

- Some of those molecules are better constructors, enabling more complex assemblies.

- Selection amplifies better constructors, creating a constructor ratchet that climbs assembly space.

The result? Life is the process by which assembly space and constructor space co-evolve. Higher assembly index objects require more sophisticated constructors, which themselves have high assembly index, which require selection to produce, which requires replication, which is enabled by high-AI molecules acting as constructors.

It's circular—but not viciously so. It's a bootstrapping loop, where each step enables the next.

Why Chemistry Is Special: Constructor-Theoretic Foundations

If selection is a constructor-generating process, why does it work so well in chemistry but not (usually) in physics?

Constructor Theory provides the answer: Chemistry offers the right substrate properties for constructor emergence.

Specifically:

Modularity: Molecules are discrete, combinatorial objects. You can join them, break them, rearrange them without fundamentally altering their identity. This allows iterative assembly.

Stability: Covalent bonds are strong enough to preserve structures over many thermal fluctuations but weak enough to be broken and reformed by available energy sources.

Information substrate: Molecular sequences (nucleotides, amino acids) can encode arbitrary information that specifies constructors. DNA doesn't just store data; it specifies tasks (make this protein) and constructors (the protein itself).

Environmental coupling: Chemical systems are open—they exchange matter and energy with their environment. This prevents thermal equilibrium death and provides free energy to drive constructor action.

Catalysis: Molecules can lower activation barriers for specific reactions without being consumed. This is constructor behavior at the molecular level.

These aren't arbitrary features. They're necessary conditions for evolutionary constructors to emerge. Physics at larger scales (solid-state, planetary) lacks modularity. Physics at smaller scales (particle physics) lacks stability over time. Chemistry sits at the Goldilocks scale where constructors can bootstrap complexity.

Assembly Theory quantifies this: molecules with AI > 15 don't appear in non-living chemistry. Constructor Theory explains why: they require evolved constructors to assemble, and evolved constructors only emerge where the substrate supports the task of self-replication with variation and selection.

Beyond Biology: Cultural and Cognitive Constructors

If selection is a constructor for producing constructors, does this framework apply beyond biology?

Increasingly, researchers argue yes. Consider:

Cultural evolution: Memes (ideas, practices, technologies) are information structures that replicate with variation and selection. A useful idea spreads; a bad one dies. But crucially, ideas are constructors—they cause transformations in human behavior and material culture. "How to make fire" is a constructor for the task of ignition. "How to smelt iron" is a constructor for the task of metallurgy.

Cultural evolution is a selection process operating in cognitive assembly space—the space of possible ideas and their combinations. Just as biological selection climbs molecular assembly space by producing molecular constructors, cultural selection climbs conceptual assembly space by producing conceptual constructors (technologies, institutions, languages).

Technological evolution: Each technology is a constructor that enables new tasks. The wheel enables transportation. The printing press enables mass information replication. The internet enables global coordination. Each constructor enables the creation of more complex constructors.

Cognitive systems: Your brain is a prediction machine, yes—but from a constructor-theoretic view, it's a constructor-generation system. It builds internal models (constructors for prediction tasks) and updates them through error-driven learning (a selection process). The task of the brain isn't just to predict—it's to construct better constructors for prediction.

This isn't metaphor. These systems exhibit the same structural properties:

- Replication (ideas spread, models update)

- Variation (new ideas, modified models)

- Selection (useful ideas survive, accurate models dominate)

- Constructor emergence (new technologies, new cognitive strategies)

The mathematics is different—cognitive assembly space isn't molecular assembly space—but the logic is identical. Selection processes are constructors for producing constructors, whether the substrate is chemistry, culture, or computation.

The Deep Convergence: Assembly, Construction, and Coherence

Let's zoom out to see the full picture.

Assembly Theory tells us that complexity is measurable by construction depth. High assembly index objects require many steps to build from elementary parts.

Constructor Theory tells us that physical possibility is characterized by which tasks can be performed by which constructors.

Together, they reveal: Selection is the physical process by which constructor-rich regions of assembly space become accessible.

But there's a third framework lurking here, one that regular readers of Ideasthesia will recognize: coherence geometry.

Coherence, in the AToM framework (M = C/T), is a measure of how well a system's dynamics hang together over time. High coherence systems exhibit stable, predictable, integrable trajectories. Low coherence systems fragment, fail to predict, accumulate error.

Notice the structural parallel:

- High assembly index = many construction steps = information-rich structure

- High constructor capacity = ability to perform complex tasks reliably

- High coherence = low prediction error = stable dynamics over time

These aren't three separate properties. They're three perspectives on the same underlying phenomenon: organized complexity that persists because it enables its own persistence.

A high-AI molecule persists because its structure enables functional tasks (constructor capacity) that lead to its own replication (coherence over time). The selection process that produces it is itself a high-coherence dynamical system—it reliably produces high-AI outcomes across generations.

In AToM terms: Selection is a coherence-generating process operating in assembly space via constructor production.

Or more simply: Meaning (M) emerges when constructors (C) persist over time (T).

This is why Assembly Theory and Constructor Theory feel so conceptually aligned with coherence geometry. They're all describing the physics of how organized complexity becomes self-sustaining—just from different angles.

Assembly Theory: What gets built?

Constructor Theory: What enables building?

Coherence Theory: Why does it persist?

The answer to all three: Selection as constructor-generating process.

Implications: From Molecules to Minds

If this framework is correct, several predictions follow:

1. Biosignature detection: We can search for life on other worlds by looking for molecular ensembles with high assembly index and high copy number. No need to assume Earth-like biochemistry—just look for the constructor signature.

2. Origin of life: Life emerges where physical conditions allow iterative assembly of molecules with increasing constructor capacity. Not a single critical event (first replicator) but a gradual climb through assembly space via evolving constructors.

3. Open-ended evolution: Systems exhibit open-ended complexity growth when they can produce constructors that enable the construction of novel constructors. Biology does this via genetic coding. Culture does this via language and technology. AI might do this via learned world models.

4. Cognitive convergence: Minds aren't uniquely biological. Any physical system that iteratively constructs better predictors of its environment via selection on model error is building constructors in cognitive assembly space. Brains, AI systems, even immune systems.

5. Meaning generation: Meaning isn't subjective or mystical. It's the coherence property of high-AI cognitive structures—ideas, narratives, identities—that act as constructors for prediction tasks. Selection on prediction error (free energy minimization) drives cognitive assembly just as selection on replication success drives molecular assembly.

These aren't speculations. They're testable implications of taking Constructor Theory and Assembly Theory seriously together.

Challenges and Open Questions

This synthesis isn't without problems. Several key challenges remain:

Quantifying constructor capacity: How do we measure how good a constructor is at performing a task? Assembly index measures object complexity, but constructor quality requires task-specific metrics.

Constructor composition: How do constructors combine? Can we predict the constructor capacity of a system from its parts? This is the compositionality problem in a new guise.

Selection without replication: Some selection processes don't involve replication (neural Darwinism, immune selection). Can Constructor Theory accommodate these? Or does constructor emergence always require copying?

Thermodynamic constraints: Constructors require free energy. How do thermodynamic limits constrain constructor space? Can we derive assembly bounds from thermodynamic principles?

Cognitive assembly space: How do we define assembly index for ideas, not molecules? What are the elementary units? What counts as a joining operation? This remains deeply unclear.

Coherence formalization: The link between assembly index, constructor capacity, and coherence geometry is conceptually compelling but mathematically underspecified. We need formal proofs, not just analogies.

These aren't fatal objections. They're the research frontier—the place where Assembly Theory, Constructor Theory, and coherence geometry meet and demand synthesis.

Further Reading

- Cronin, L., & Walker, S. I. (2023). "Assembly Theory Explains and Quantifies Selection and Evolution." Nature.

- Marletto, C. (2021). "Constructor Theory of Life." Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

- Deutsch, D., & Marletto, C. (2015). "Constructor Theory of Information." Proceedings of the Royal Society A.

- Walker, S. I., et al. (2017). "Exoplanet Biosignatures: Future Directions." Astrobiology.

- Friston, K. (2019). "A Free Energy Principle for a Particular Physics." arXiv preprint.

This is Part 5 of the Assembly Theory series, exploring how molecular complexity, selection, and physical law converge to explain life and meaning.

Previous: Beyond Shannon: How Assembly Theory Differs from Information Theory

Next: From Molecules to Meaning: Can Assembly Theory Scale to Cognitive Systems?

Comments ()