Synthesis: Sequences and Series as the Language of Patterns

Sequences and series are how mathematics writes "and then, and then, and then..."

A sequence is a pattern with positions. A series is what accumulates when you add the pattern up. Together, they capture two fundamental operations: extending a rule and summing the results.

This sounds simple. It is simple. And from this simplicity emerges the entire theory of infinite processes.

The Core Insight

The deepest idea in this series isn't a formula. It's this:

Infinite addition can have finite results.

Not always. But sometimes. The geometric series 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + ... sums to exactly 1. The harmonic series 1 + 1/2 + 1/3 + ... sums to infinity.

The difference isn't whether there are infinitely many terms. Both have infinitely many. The difference is whether the terms shrink fast enough.

This is the partition: convergent series (finite sum) versus divergent series (infinite or undefined). Every series falls on one side.

What Determines Convergence

The terms must approach zero—that's necessary but not sufficient.

What's sufficient depends on the series type:

Geometric: Converges when |r| < 1. The ratio between terms determines everything.

p-series: Converges when p > 1. The harmonic series (p = 1) is the boundary.

Alternating: Converges if terms decrease to zero. The alternation creates cancellation.

General: Compare to known series, use ratio/root tests, or integrate.

The convergence tests are detective tools. They determine which side of the partition a series falls on without computing the sum.

The Formulas That Matter

Three formulas handle most cases:

Arithmetic series: Sₙ = n(a₁ + aₙ)/2

The sum of an arithmetic sequence. Pair first with last, multiply by half the count.

Finite geometric series: Sₙ = a₁(1 - rⁿ)/(1 - r)

The sum of a geometric sequence. Derived by the multiply-and-subtract trick.

Infinite geometric series: S = a₁/(1 - r), when |r| < 1

The limit as n → ∞. The most useful formula in series theory.

These three formulas—or variations of them—handle arithmetic sequences, geometric sequences, and their sums.

Recursion: The Third Pattern

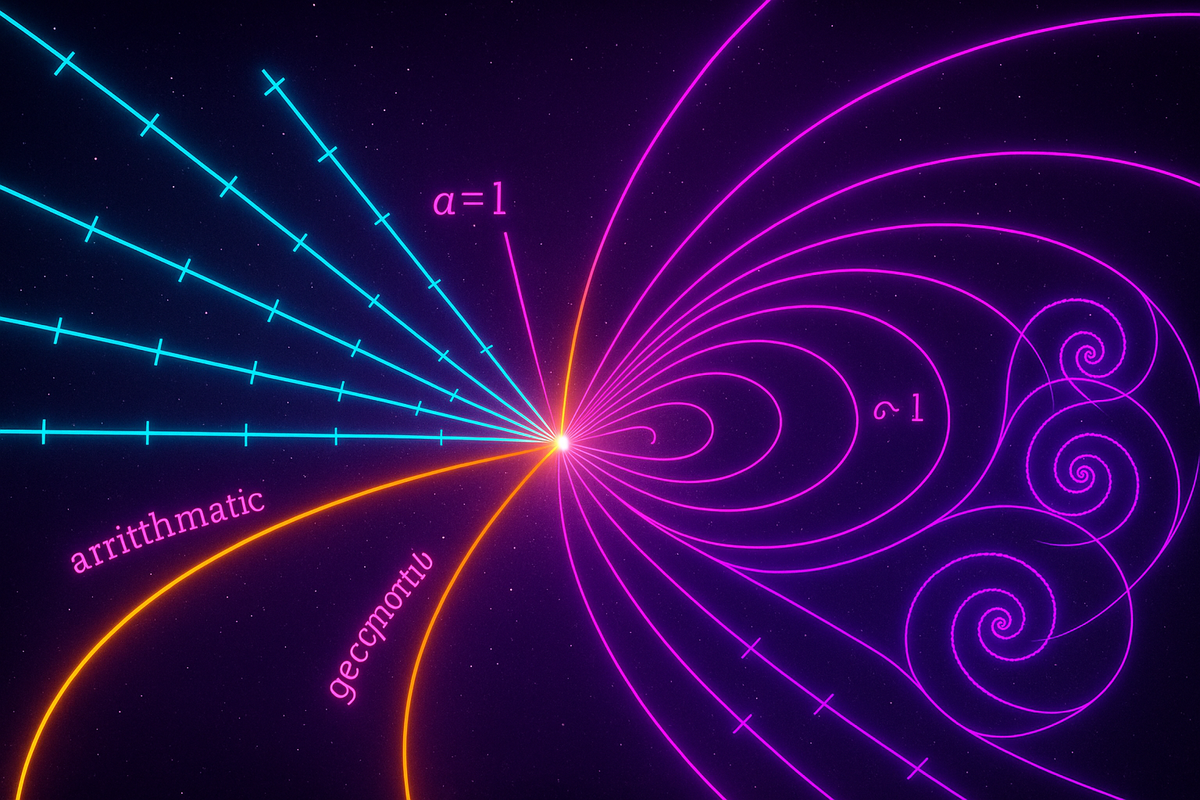

Beyond arithmetic (add constant) and geometric (multiply constant), there's recursive.

Recursive sequences define each term using previous terms. Fibonacci is the prototype: Fₙ = Fₙ₋₁ + Fₙ₋₂.

Remarkably, recursive sequences often have closed forms that are sums of exponentials. The characteristic equation method transforms difference equations into algebraic equations.

This reveals: recursion isn't a third fundamental type. Recursive sequences are often geometric in disguise—sums of exponential growth patterns.

Power Series: The Infinite Polynomial

The culmination of series theory is the power series:

f(x) = c₀ + c₁x + c₂x² + c₃x³ + ...

Power series turn functions into infinite polynomials. They're why calculators can compute sin, cos, and exp.

The key properties:

- Radius of convergence determines where the series works

- Term-by-term differentiation and integration preserve convergence

- Maclaurin/Taylor series express smooth functions as power series

Power series are the bridge between discrete sequences and continuous functions.

The Hierarchy

We've moved through layers:

- Finite sequences: Lists of numbers

- Infinite sequences: Lists that never end

- Finite series: Sums of finite sequences

- Infinite series: Limits of partial sums

- Power series: Functions as infinite series

Each layer builds on the previous. Sequences become series by summing. Series become power series by introducing variables.

Applications Everywhere

Finance: Compound interest, present value, annuity formulas—all geometric series.

Computer science: Algorithm analysis, recurrence relations, complexity bounds.

Physics: Fourier series decompose signals. Perturbation series approximate solutions.

Calculus: Taylor series enable approximation. Riemann sums define integrals.

Number theory: Euler's product formula connects primes to infinite series.

Any field that deals with accumulation, approximation, or infinite processes uses sequences and series.

The Philosophy

Sequences and series extend arithmetic beyond the finite.

Addition is easy: 2 + 3 = 5. Adding a million numbers is tedious but conceptually the same.

Adding infinitely many numbers is different. It requires limits, convergence tests, and careful definitions. But when it works, it works powerfully.

The infinite is not inherently undefined. It's defined carefully, through limits of finite processes. The sequence of partial sums approaches a limit. That limit is the infinite sum.

This is how mathematics tames infinity: not by accessing it directly, but by approaching it through finite approximations.

What We've Learned

- Sequences are patterns with positions. Know the rule, know any term.

- Series are sums of sequences. Partial sums reveal whether the infinite sum converges.

- Arithmetic sequences have constant differences. Their series diverge (unless trivial).

- Geometric sequences have constant ratios. Their series converge when |r| < 1.

- Recursive sequences look backward. They often reduce to exponential forms.

- Convergence requires terms to shrink—fast enough. The divergence test (terms → 0) is necessary but not sufficient.

- Power series represent functions. Smooth functions are infinite polynomials.

The language of sequences and series is the language of patterns, accumulation, and limits. It's how mathematics describes processes that repeat, grow, and converge.

And the central miracle remains: sometimes, adding forever gives you a finite answer.

Part 12 of the Sequences Series series.

Comments ()