Sickle Cell Cured: The First CRISPR Miracle

Victoria Gray remembers the pain.

Not just remembers—her body remembers. Thirty-four years of sickle cell crises, episodes where her blood cells jammed in her vessels like a traffic pileup, starving her tissues of oxygen. The pain would come like being stabbed with hot knives, she said. It would last days. Sometimes weeks. She'd end up in the hospital, doped on morphine, waiting for her body to clear the logjam.

Her first crisis hit at three months old. By adulthood, she'd spent more time in hospitals than most people spend on vacation. She couldn't plan her life. Couldn't commit to jobs. Couldn't promise her kids she'd make it to their school events. The disease was a thief, stealing her future one crisis at a time.

In July 2019, doctors at Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville removed some of Victoria's bone marrow cells, shipped them to a lab, and edited them with CRISPR. Then they destroyed her remaining bone marrow with chemotherapy and infused the edited cells back into her body.

Four years later, she hasn't had a single crisis.

Victoria Gray was the first American treated with CRISPR for a genetic disease. She's not cured in the careful, hedged language of medicine. She's cured in the way that matters: she has her life back.

The One-Letter Disease

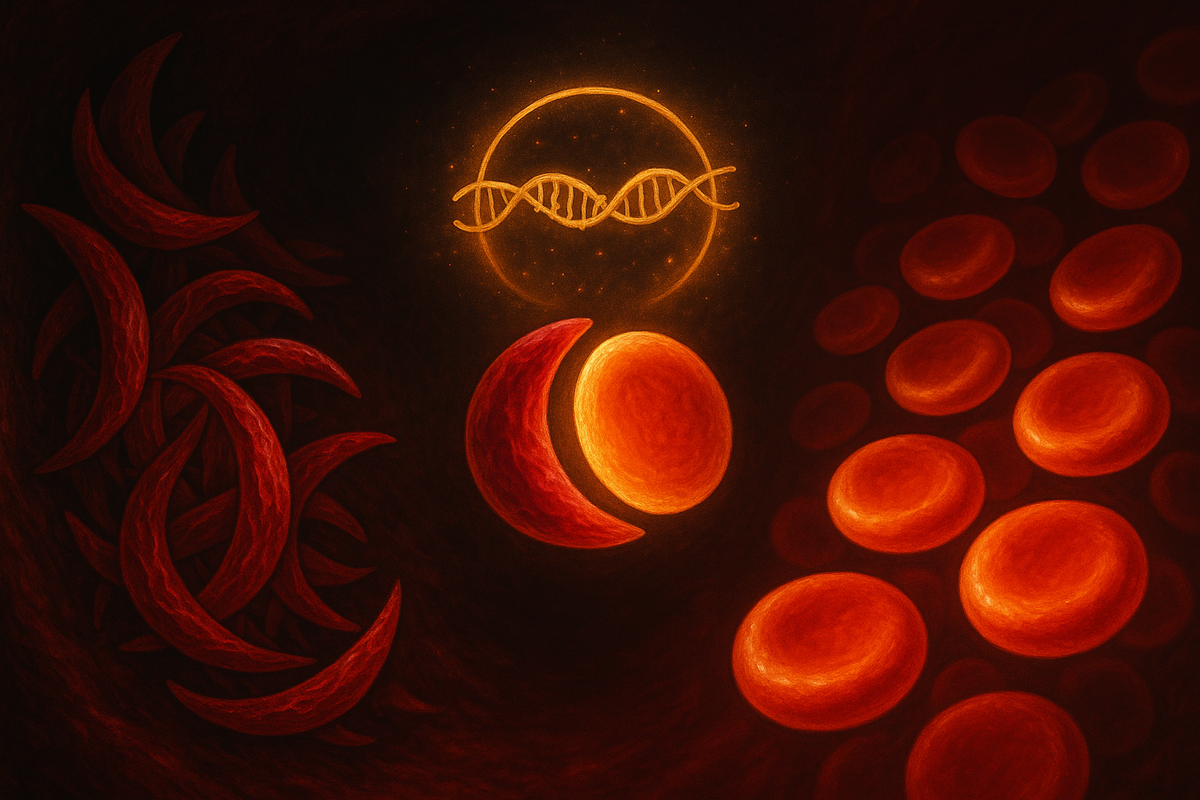

Sickle cell disease is caused by a single typo.

Your red blood cells carry hemoglobin—the protein that grabs oxygen in your lungs and releases it in your tissues. Hemoglobin is made of two types of protein chains, alpha and beta, encoded by genes you inherited from your parents. In sickle cell disease, one letter of the beta-globin gene is wrong: an A where there should be a T.

One letter. Out of three billion in your genome. And it changes everything.

That single mutation causes the hemoglobin molecules to stick together when they release oxygen. The sticky hemoglobin forms long fibers inside the red blood cell, distorting it from a soft, flexible disc into a rigid crescent—a sickle. These sickled cells can't squeeze through narrow capillaries. They jam. They block blood flow. Tissues downstream starve. Pain receptors scream.

And it gets worse. Sickled cells are fragile. They burst easily, leading to chronic anemia. The debris from burst cells damages blood vessel walls, causing organ damage that accumulates over decades. Sickle cell patients have shorter lifespans, higher rates of stroke, kidney failure, lung problems, and constant vulnerability to infections.

The disease is ancient. The sickle mutation arose independently multiple times in human history, in Africa, the Middle East, and India—wherever malaria was endemic. Because here's the cruel tradeoff: one copy of the sickle gene protects against malaria. Two copies give you sickle cell disease. Evolution kept the mutation around because malaria killed more people than sickle cell did.

About 100,000 Americans have sickle cell disease. Worldwide, hundreds of thousands of children are born with it every year, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. For most of medical history, treatment meant managing symptoms—transfusions for anemia, painkillers for crises, antibiotics for infections. The underlying genetic error couldn't be touched.

Until now.

The Clever Workaround (Fetal Hemoglobin)

Here's the elegant part: Casgevy, the CRISPR therapy that treated Victoria Gray, doesn't actually fix the sickle mutation.

It uses a workaround. And the workaround reveals something beautiful about human biology.

Before you were born, you made a different kind of hemoglobin. Fetal hemoglobin grabs oxygen more tightly than adult hemoglobin—it has to, because a fetus needs to pull oxygen across the placenta from its mother's blood. After birth, a genetic switch flips. Your body stops making fetal hemoglobin and starts making adult hemoglobin. The fetal genes are still there, intact, but they're silenced.

In sickle cell patients, the fetal hemoglobin genes are perfectly healthy. The sickle mutation only affects adult beta-globin. If you could flip the switch back—reactivate fetal hemoglobin production—you'd flood the red blood cells with normal hemoglobin. The sickled hemoglobin would be diluted. The cells would stay round. The crises would stop.

For decades, researchers tried to find that switch. They found it in a gene called BCL11A, which acts as a repressor—it keeps fetal hemoglobin turned off in adults. Disable BCL11A, and fetal hemoglobin comes flooding back.

Casgevy uses CRISPR to break BCL11A.

Specifically, it targets a region of BCL11A that's only active in red blood cell precursors. You don't want to disable BCL11A everywhere—it has other jobs in the immune system. But in the cells that become red blood cells? Break it. Let the fetal hemoglobin flow.

They're not fixing the typo. They're turning back the clock to before the typo mattered.

The Treatment Journey (It's Brutal)

Let's be clear about what "gene therapy" actually involves. It's not a pill. It's not a shot. It's one of the most intense medical procedures a patient can undergo.

Step 1: Harvest. Doctors extract stem cells from the patient's bone marrow—the cells that will become all future blood cells. This is done through multiple sessions of apheresis, where blood is drawn, stem cells are filtered out, and the rest is returned.

Step 2: Edit. The stem cells are shipped to a manufacturing facility where they're edited with CRISPR. The editing happens outside the body—ex vivo—because we don't yet have reliable ways to deliver CRISPR directly to bone marrow stem cells inside a living patient. Quality control is intense. Every batch has to be tested to ensure the edits worked and didn't introduce dangerous mutations.

Step 3: Destroy. Before the edited cells can be returned, the patient's remaining bone marrow has to be wiped out. This is done with high-dose chemotherapy—the same brutal regimen used before bone marrow transplants. It's necessary because you need to make room for the new cells and prevent the old, unedited cells from outcompeting them.

This step is rough. Patients lose their immune systems. They're vulnerable to infections. They lose their hair. They experience nausea, fatigue, mouth sores. They spend weeks in the hospital in protective isolation.

Step 4: Infuse. The edited cells are transfused back into the patient's bloodstream. They migrate to the bone marrow and start producing new blood cells—blood cells that now express fetal hemoglobin.

Step 5: Wait. It takes months for the new cells to fully engraft and populate the bone marrow. During this time, patients remain fragile and monitored.

Victoria Gray spent months in the hospital. The chemotherapy was miserable. But when her new blood cells started appearing, her fetal hemoglobin levels climbed. Within a year, her hemoglobin was over 90% fetal. Her sickle cells became rare. Her crises stopped.

"I pray for this for everyone that has this disease," she said in an interview. "That they would be able to live a normal life."

The First Approval (And the Price Tag)

In December 2023, the FDA approved Casgevy for sickle cell disease. It was the first CRISPR therapy approved for a genetic condition in the United States. The same week, a second gene therapy—Lyfgenia, using a different approach—was also approved.

The price: $2.2 million per patient.

That number sounds obscene. And in many ways, it is. But context matters.

Sickle cell patients require lifelong care. Blood transfusions every few weeks. Emergency room visits for crises. Hospitalizations. Pain management. Treatment for organ damage. Disability support. Lost wages. Some estimates put the lifetime cost of managing a sickle cell patient at $1.7 million to $2.5 million—and that's before you factor in the incalculable cost of suffering, of a life lived around a disease.

Casgevy offers a potential one-time cure. Pay once. No more transfusions. No more crises. No more lifetime of management. If the cure holds—and early data suggests it does—the economics might actually work.

But "might work" depends entirely on who's paying.

In the U.S., private insurers and Medicare are negotiating coverage. Some are exploring outcomes-based contracts: pay less upfront, more if the cure works. Novel financing models are emerging. But the infrastructure for $2 million therapies doesn't really exist.

In sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of sickle cell patients live, $2.2 million is impossible. It's not just expensive—it's in a different economic universe. A therapy that could cure sickle cell globally will remain a therapy for wealthy nations unless something changes dramatically.

The technology is here. The delivery system isn't.

The Other Approach (Gene Addition vs. Gene Editing)

Casgevy edits genes. Lyfgenia, the other approved therapy, uses a different approach: it adds genes.

Lyfgenia uses a lentiviral vector—a modified virus—to deliver a healthy copy of the beta-globin gene directly into the patient's stem cells. The sickle mutation stays, but now there's a new, working copy of the gene producing normal hemoglobin alongside it.

This is classic gene therapy, the approach scientists dreamed about in the 1990s. It finally works—but it took decades of refinement to make the viral vectors safe and effective.

The two approaches have different risk profiles. Gene editing with CRISPR is more precise—you're making a specific change to a specific location. But CRISPR can occasionally cut in the wrong place (off-target effects), potentially causing unintended mutations. Gene addition doesn't rely on cutting, but viral vectors can integrate randomly into the genome, occasionally disrupting important genes.

Both approaches require the same brutal chemotherapy conditioning. Both require the same hospitalization and recovery period. Both cost roughly the same.

In clinical trials, both work. Patients on both therapies show dramatic increases in healthy hemoglobin and dramatic reductions in vaso-occlusive crises. Which one "wins" may come down to long-term safety data, manufacturing efficiency, and the economics of healthcare systems.

For patients like Victoria Gray, the technical details matter less than the outcome: a life without sickle cell crises.

What Cure Means (And What It Doesn't)

We should be careful with the word "cure."

In clinical trials, Casgevy eliminated vaso-occlusive crises in 93% of patients followed for at least two years. That's extraordinary. But "no crises" isn't the same as "no disease."

Some patients still have low levels of sickled cells. Some still have chronic anemia. The organ damage accumulated over decades before treatment doesn't reverse. If you had silent strokes as a child, those effects remain.

And we don't know how long the cure lasts. The edited cells are self-renewing—they're stem cells, so they should produce edited blood cells indefinitely. But indefinitely is hard to prove when the longest follow-up is only a few years. Will the edited cells persist for a decade? Two decades? A lifetime? We don't know yet.

There are also patients for whom the therapy doesn't work as well. Engraftment can fail. Fetal hemoglobin levels can be lower than hoped. Some patients still experience crises, just fewer of them. Gene therapy isn't magic—it's medicine, with all medicine's variability.

But for the patients who respond well? For Victoria Gray and others like her?

The difference is the difference between a life defined by disease and a life defined by possibility. Victoria has gone back to work. She watches her children grow up. She makes plans. She lives.

That's what cure means in practice.

The Pipeline Beyond Sickle Cell

Casgevy is first, but it won't be last.

CRISPR Therapeutics (the company behind Casgevy) and Vertex Pharmaceuticals are testing the same approach for beta-thalassemia, another hemoglobin disorder. Early results look similar—high levels of transfusion independence, reduced disease burden.

Beam Therapeutics is developing a base editing approach for sickle cell that might directly correct the sickle mutation rather than reactivating fetal hemoglobin. If successful, it would be a true repair rather than a workaround.

Other companies are working on in-vivo approaches—delivering CRISPR directly into the body, avoiding the need for stem cell extraction and chemotherapy conditioning. This could make gene therapy accessible to far more patients. If you could inject a one-time treatment instead of undergoing bone marrow ablation, the calculus changes entirely.

The dream is a shot that fixes sickle cell. Show up at a clinic. Get an injection. Go home cured. That's still years away. But it's no longer fantasy.

What Victoria Gray Proved

Victoria Gray wasn't just the first patient. She was proof of concept for an entire field.

For decades, gene therapy was a promise that kept failing. Trial after trial disappointed. Patients died in early experiments. Vectors caused cancer. The technology wasn't ready.

Casgevy represents the moment when the technology finally arrived. Not perfect—the treatment is still brutal, expensive, and limited. But functional. The first true genetic cure for a disease that has tormented humanity for millennia.

Victoria Gray's blood cells now carry edited DNA. Her children won't inherit those edits—this isn't germline modification—but they can inherit the hope. The hope that one day, sickle cell disease will be something their grandchildren only read about in history books.

A disease caused by one wrong letter, corrected by molecular scissors.

That's what the CRISPR revolution looks like when it reaches patients.

Further Reading

- Frangoul, H. et al. (2021). "CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing for Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia." New England Journal of Medicine. - Kanter, J. et al. (2022). "Outcomes in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease Treated with CTX001." Blood. - U.S. FDA (2023). "FDA Approves First Gene Therapies to Treat Patients with Sickle Cell Disease." Press release. - NPR (2022). "Victoria Gray's story: The first U.S. patient to receive CRISPR gene therapy."

This is Part 5 of the CRISPR Revolution series. Previous: "Gene Drives." Next: "Off-Target Effects"—what happens when molecular scissors cut in the wrong place? The safety question that keeps researchers up at night.

Comments ()