Simple vs Complex Contagions

For twenty years, everyone knew how ideas spread. Malcolm Gladwell had explained it in The Tipping Point. Mark Granovetter had proved it with "The Strength of Weak Ties." The conventional wisdom was clear: information spreads fastest through weak connections—acquaintances, not close friends. If you want something to go viral, bridge different social clusters. Connect the unconnected.

Then Damon Centola ran the experiment and broke the model.

His finding was simple and devastating: the viral spread model only works for information. For behavior change, it fails completely. Getting people to know something and getting people to do something follow opposite network dynamics.

This distinction—between simple and complex contagions—is one of the most important ideas in network science. And almost no one outside academia knows it.

The Granovetter Orthodoxy

In 1973, Mark Granovetter published a paper that would become one of the most cited in sociology. "The Strength of Weak Ties" argued that acquaintances—people you know slightly, not your close friends—are more valuable for spreading information than strong ties.

The logic was intuitive. Your close friends know mostly the same people you know. Their information overlaps with yours. But acquaintances move in different circles. They're bridges to other clusters. When you need a job lead or a new idea, it's your weak ties who deliver.

This became gospel. Network theorists built models on it. Marketers designed campaigns around it. The entire field of viral marketing assumed that bridging weak ties was the key to spread.

The assumption seemed validated by how information actually moves online. A tweet goes viral not because your best friend shares it, but because it hops across weak-tie bridges into new networks. A YouTube video spreads through acquaintance shares. The weak-tie model explained what everyone observed.

But there was a category error hiding in the model.

The Centola Experiments

Damon Centola, a sociologist at UPenn, noticed something odd. The viral spread model predicted that health behaviors should spread the same way information spreads—through weak ties, across bridges. But public health interventions kept failing when they relied on this logic.

Telling people about condom use was easy. Getting them to actually use condoms was hard. Awareness campaigns spread virally; behavior change didn't.

Centola designed an experiment to test why. He created online communities where people could adopt or not adopt a health behavior—signing up for a health forum. Some communities had network structures optimized for weak-tie spread (low clustering, many bridges). Others had structures optimized for strong-tie spread (high clustering, dense local connections).

The results inverted the conventional wisdom.

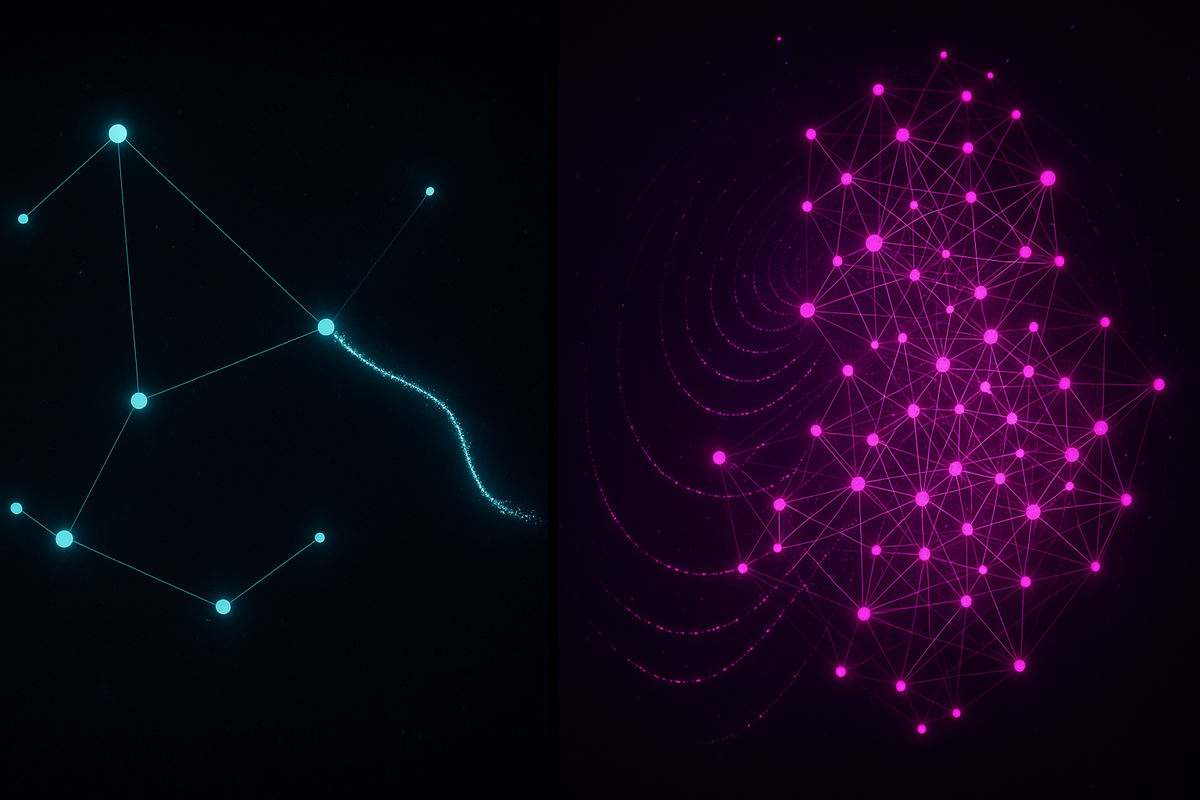

Simple contagions—things that spread on a single exposure, like information or awareness—spread faster through weak ties. The viral model worked perfectly.

Complex contagions—things that require reinforcement to spread, like behavior change or risky adoption—spread faster through strong ties and clustered networks. The weak-tie bridges that accelerated simple contagions actually blocked complex contagions.

Why? Because complex contagions need social proof. You don't change your behavior because one acquaintance mentioned something. You change your behavior when multiple trusted sources model it, when the social norm in your immediate cluster shifts, when adoption feels safe because your close friends have already done it.

The Mechanics of Complexity

What makes a contagion "complex"?

Risk. Adopting a new behavior involves potential costs—social embarrassment, wasted effort, actual danger. Before you take the risk, you want to see others take it first. One person isn't enough. You need multiple independent sources confirming it's safe.

Credibility. Information from a single source might be wrong. Information from multiple independent sources is more credible. The redundancy isn't wasteful—it's verification.

Legitimacy. Some behaviors require social permission. You can't adopt them unless enough of your immediate social circle has adopted them first. A single early adopter isn't permission. A cluster of adopters is.

Complementarity. Some behaviors are only valuable if others do them too. A phone is only useful if people you want to call also have phones. Adoption requires coordination, not just exposure.

All of these factors create threshold effects. Instead of spreading on single exposure (like measles), complex contagions spread only when exposure exceeds some threshold—two friends, three friends, a majority of your circle.

The threshold varies by person and by behavior. Some people need to see three friends adopt before they'll try something new. Others need a majority of their circle. Risk-averse individuals have high thresholds; early adopters have low ones. But the key insight is that thresholds exist at all. Simple contagions have no threshold—one exposure is enough. Complex contagions are defined by the threshold requirement.

And threshold effects completely change optimal network structure.

Why Bridges Fail

Here's the counterintuitive result: the network features that accelerate simple contagions actively impede complex contagions.

Bridges—connections between otherwise separate clusters—are valuable for simple contagions because they extend reach. One exposure is enough for transmission, so more reach means more spread.

But bridges are terrible for complex contagions. A single bridge delivers only one exposure to the new cluster. If adoption requires two or more sources, the bridge transmission fails. The contagion reaches the new cluster, but no one adopts.

Wide bridges—multiple connections between clusters—solve this. If three people in Cluster A are connected to three people in Cluster B, complex contagions can cross. The redundancy that seems inefficient for information spread is essential for behavior spread.

Similarly, clustering—dense local connections where everyone knows everyone—impedes simple contagions (by limiting reach) but accelerates complex contagions (by providing reinforcement). When your whole friend group adopts something, you adopt it. The social proof is overwhelming.

This explains why behavior change campaigns keep failing. They're designed for simple contagions—maximize reach, cross bridges, go viral. But behavior change is a complex contagion that needs the opposite: concentrate influence, build redundancy, create clusters of adoption.

The Innovation Diffusion Problem

This framework resolves a long-standing puzzle in innovation studies.

Everett Rogers, in Diffusion of Innovations, documented that new technologies follow an S-curve of adoption: slow start, rapid acceleration, gradual saturation. But the model never explained why the early phase was so slow, or why some innovations got stuck there permanently.

The complex contagion framework explains it. Early adoption is slow because early adopters are isolated. They're scattered across the network, connected by weak ties. Each one is the only person in their local cluster who's adopted. They can spread awareness (simple contagion) but not adoption (complex contagion).

The inflection point comes when adopters start clustering. When you have neighborhoods or friend groups where multiple people have adopted, the complex contagion kicks in. Now adoption spreads through local reinforcement. The S-curve accelerates.

Innovations that never reach this threshold get stuck in early adoption forever. There are enough scattered early adopters to sustain awareness but not enough clustered adopters to trigger the cascade.

The lesson for anyone trying to spread a behavior: don't maximize reach. Maximize density. A hundred scattered early adopters may be less effective than twenty adopters clustered in the same social space.

Online vs Offline

Social media should, in theory, turbocharge contagions. More connections, faster transmission, global reach. And for simple contagions—information, awareness, memes—it does exactly that.

But for complex contagions, social media may actually impede spread.

Online networks tend to have low clustering and many bridges. Great for viral information. Terrible for behavior change. Your Twitter followers don't form a dense cluster of trusted sources. They're weak ties scattered across the network.

This explains a persistent puzzle: why does so much online activism fail to translate into offline behavior? The information spreads virally. Everyone becomes aware. But awareness is a simple contagion. Behavior change is complex. And online network structures are optimized for simple, not complex.

Hashtag awareness ≠ behavioral adoption. The same network that makes the hashtag go viral makes the behavior change impossible to sustain.

Consider the Ice Bucket Challenge—one of the most successful viral campaigns ever. The awareness spread through classic weak-tie viral dynamics. Everyone saw it. But the actual behavior (donating to ALS research) required a hybrid approach: the viral video created social pressure within local clusters. You didn't donate because a stranger did. You donated because your actual friends did, and they tagged you, and now your local cluster was watching.

The campaigns that fail are the ones that assume viral awareness automatically converts to action. "Kony 2012" achieved massive viral reach—the video was viewed 100 million times in six days. But the organization behind it couldn't convert that awareness into sustained action. The network structure that spread the video was precisely wrong for spreading commitment.

Centola's later research suggested that online behavior change requires creating "reinforcement clusters"—small dense groups where members see multiple others adopting. Not viral broadcast, but intensive local coordination. Not reach, but depth.

Political Implications

The simple/complex distinction has profound implications for political mobilization.

Getting people to believe something politically is relatively easy. Political information spreads through weak ties like any other information. A single exposure to a meme or headline can shift a belief, at least temporarily.

Getting people to act politically—to vote, to donate, to protest, to organize—is complex contagion territory. It requires reinforcement. It requires seeing multiple trusted others take the same action. It requires local clustering.

This explains why social media is so effective at spreading political beliefs and so ineffective at generating political action. The beliefs go viral; the actions don't. The Arab Spring spread awareness across the entire region in days. Sustaining the political movements required dense local organizing that the same networks couldn't provide.

Effective political mobilization needs both: viral spread to build awareness, then local clustering to convert awareness into action. The failure mode is assuming that viral awareness is enough.

The Contagion Taxonomy

Centola's framework suggests a taxonomy of contagions:

Simple contagions (spread on single exposure): - News and information - Awareness of an idea - Emotional reactions (sometimes) - Memes and jokes

Complex contagions (require reinforcement): - Behavior change - Risky adoption (new technology, new practice) - Norm change (what's acceptable) - Sustained commitment (not just one-time action)

Hybrid contagions (start simple, become complex): - Political beliefs (easy to shift temporarily, hard to sustain) - Health behaviors (easy to know about, hard to do) - Social movements (easy to support symbolically, hard to participate actively)

The strategy for spreading each is different. Simple contagions want bridges and reach. Complex contagions want clusters and reinforcement. Hybrid contagions need a two-stage approach: viral for awareness, then intensive for action.

Most people designing interventions—in public health, marketing, social movements—don't make this distinction. They assume all contagions are simple, design for viral reach, then wonder why their campaigns spread awareness but not adoption. They've optimized for the wrong type of spread.

The Reversal

Here's the deepest implication of Centola's work: Granovetter was exactly right about information and exactly wrong about everything else.

For a generation, network theorists had been building on "The Strength of Weak Ties" as if it were a universal law of spreading. But it's only a law for a subset of contagions—the least consequential subset. News spreads through weak ties. Memes spread through weak ties. But the things that actually change behavior—norms, habits, commitments—spread through strong ties.

We built the internet to maximize weak-tie connections. We optimized for viral spread, for bridging clusters, for information velocity. And we got exactly what we optimized for: an engine for spreading simple contagions faster than any technology in history.

The cost was degrading the networks that spread complex contagions. Dense local clusters got replaced by sparse global connections. Strong ties got diluted by hundreds of weak ties. The redundancy that complex contagions need got optimized away in favor of reach.

We made ourselves very good at knowing things and very bad at doing things. The architecture of our networks determined what could spread—and the things that matter most got left behind.

The Takeaway

The viral model of spread is half right. For information and awareness, it works perfectly. Maximize reach, bridge clusters, let weak ties carry the message.

But for everything that actually matters—behavior change, norm change, sustained action—the viral model fails. You need the opposite: dense local clusters where multiple trusted sources model the behavior. Not reach, but depth. Not bridges, but redundancy.

The internet made us very good at spreading information and very bad at changing behavior. We optimized our networks for simple contagions and broke them for complex ones.

The next time someone tells you to "go viral," ask what you're trying to spread. If it's awareness, viral works. If it's adoption, viral is exactly wrong.

Further Reading

- Centola, D. (2018). How Behavior Spreads: The Science of Complex Contagions. Princeton University Press. - Centola, D., & Macy, M. (2007). "Complex contagions and the weakness of long ties." American Journal of Sociology. - Granovetter, M. S. (1973). "The strength of weak ties." American Journal of Sociology.

This is Part 3 of the Network Contagion series. Next: "Emotional Contagion"

Comments ()