Stokes' Theorem: Generalizing Green's Theorem to Surfaces

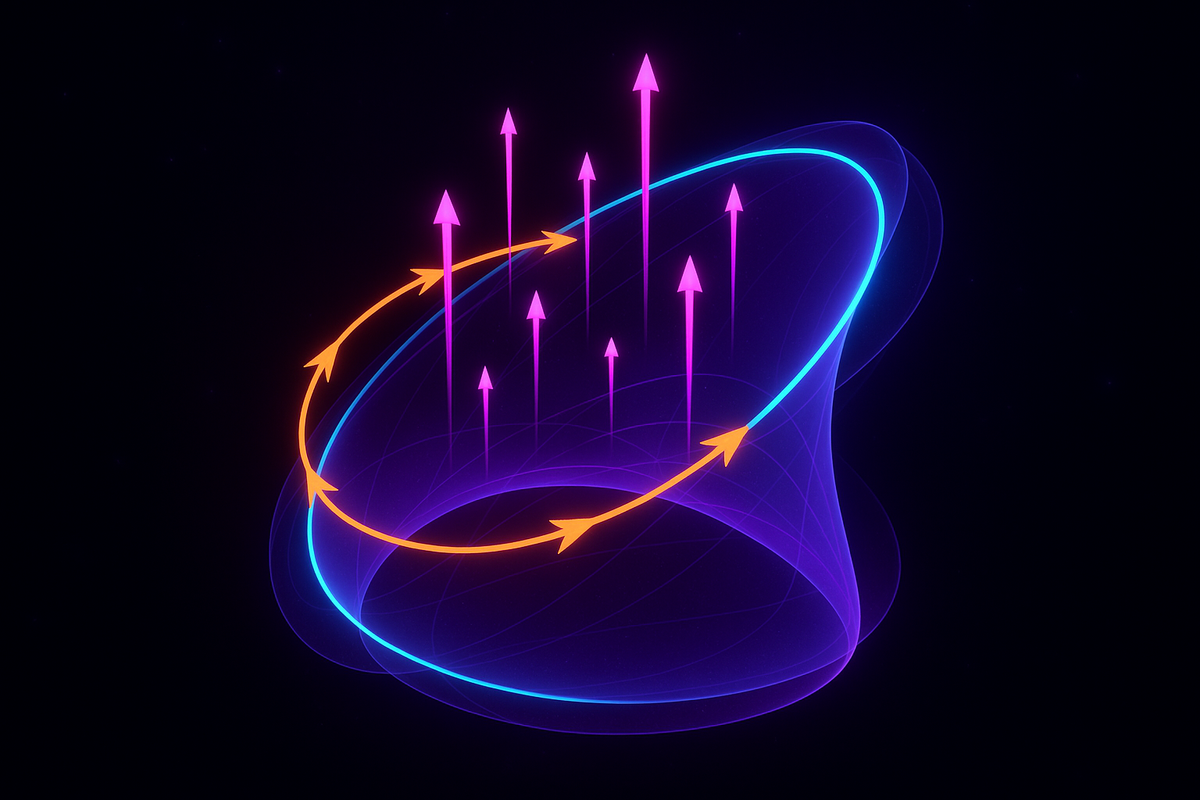

Stokes' Theorem generalizes Green's Theorem to 3D. It connects a line integral around a closed curve to a surface integral of curl over any surface bounded by that curve.

∫_C F · dr = ∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS

where C is a closed curve, S is any surface with boundary C, and F is a vector field in 3D.

This is the fundamental theorem for curl. Circulation around the boundary equals the total curl through the surface. Local rotation integrates to boundary circulation.

The beauty: you can choose any surface with the given boundary. A flat disk, a hemisphere, a crazy twisted surface—doesn't matter. The integral of curl over the surface always equals the circulation around the edge.

The Setup

You have a closed curve C in 3D space. Think of it as a loop of wire.

You have a surface S that has C as its boundary. The surface "spans" the curve like a soap film spanning a wire loop.

You have a vector field F defined in the region.

Stokes' Theorem says:

∫_C F · dr = ∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS

Line integral around the edge = Surface integral of curl through the interior.

Why It Generalizes Green's Theorem

Green's Theorem: ∫_C F · dr = ∬_R (∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y) dA

This is Stokes' Theorem for a flat surface in the xy-plane. The 2D curl (∂Q/∂x - ∂P/∂y) is the z-component of the 3D curl ∇ × F.

Stokes' extends this to curved surfaces in 3D. The surface doesn't have to be flat. It doesn't even have to be in a coordinate plane. As long as it has the curve C as its boundary, Stokes' applies.

The Geometric Picture

Imagine the surface S divided into tiny patches. For each patch, the circulation around its boundary approximately equals the curl through the patch (by a local version of Stokes').

Now add up all patches. The interiors sum to ∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS. The boundaries mostly cancel—each internal edge is traversed twice in opposite directions. Only the outer boundary C survives.

So ∑(circulation around tiny patches) = ∫_C (outer boundary) = ∫∫_S curl.

This is the telescoping idea again, now in 3D. Interior edges cancel, leaving only the boundary contribution.

Example: Hemisphere

Let F = (-y, x, 0), the rotating field around the z-axis.

∇ × F = (0, 0, 2), pointing up along the z-axis.

Let C be the circle of radius a in the xy-plane: x² + y² = a², z = 0.

Line integral around C:

Parameterize: r(t) = (a cos t, a sin t, 0), t ∈ [0, 2π] r'(t) = (-a sin t, a cos t, 0) F(r(t)) = (-a sin t, a cos t, 0) F · r' = a² sin² t + a² cos² t = a²

∫_C F · dr = ∫_0^{2π} a² dt = 2πa²

Surface integral over the flat disk:

S is the disk x² + y² ≤ a² in the xy-plane. (∇ × F) · dS = (0, 0, 2) · (0, 0, 1) dA = 2 dA

∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS = ∫∫_disk 2 dA = 2 · πa² = 2πa²

They match. Stokes' Theorem confirmed.

Surface integral over a hemisphere:

Now use S = upper hemisphere of radius a.

In spherical coordinates: r = a, θ ∈ [0, 2π], φ ∈ [0, π/2].

The normal vector to the hemisphere is radial: n = (sin φ cos θ, sin φ sin θ, cos φ).

∇ × F = (0, 0, 2).

(∇ × F) · n = 2 cos φ.

The surface element: dS = a² sin φ dφ dθ.

∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS = ∫_0^{2π} ∫_0^{π/2} 2 cos φ · a² sin φ dφ dθ

= 2a² ∫_0^{2π} dθ ∫_0^{π/2} sin φ cos φ dφ

= 2a² · 2π · [sin² φ / 2]_0^{π/2}

= 2a² · 2π · (1/2) = 2πa²

Same answer. Whether you use the flat disk or the curved hemisphere, the surface integral of curl equals the line integral around the boundary.

Surface Independence

This is the key insight: the integral ∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS depends only on the boundary C, not on the choice of surface S.

Any two surfaces with the same boundary give the same integral. This is surface independence, analogous to path independence for conservative fields.

Why? Because if you have two surfaces S₁ and S₂ with the same boundary, you can glue them together to form a closed surface (with S₂ reversed). The Divergence Theorem (applied to curl, which is divergence-free) says the integral over a closed surface is zero. So ∫∫{S₁} = ∫∫{S₂}.

Surface independence is powerful. It means you can choose the easiest surface for computation. Flat disk too hard? Use a hemisphere. Hemisphere too hard? Use another surface. The answer is the same.

Orientation and the Right-Hand Rule

Orientation matters. The curve C and the surface S must have compatible orientations.

Convention: if you walk around C in the direction of the line integral, the surface should be on your left (via the right-hand rule). Equivalently, curl your right hand in the direction of C; your thumb points in the direction of the surface normal.

If you reverse the orientation of C, you reverse the sign of the line integral. If you reverse the orientation of S (flip the normal), you reverse the sign of the surface integral. Stokes' Theorem still holds with consistent orientations.

Curl-Free Fields

If ∇ × F = 0 everywhere (curl-free field), then ∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS = 0 for any surface S.

By Stokes', ∫_C F · dr = 0 for any closed curve C.

This is why conservative fields (which are curl-free) have zero circulation around any loop. Stokes' explains the connection: zero curl integrates to zero circulation.

Applications: Faraday's Law

Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction:

∫_C E · dr = -d/dt ∫∫_S B · dS

The line integral of the electric field around a loop equals the negative rate of change of magnetic flux through the loop.

Using Stokes' on the left side:

∫∫_S (∇ × E) · dS = -d/dt ∫∫_S B · dS

If the surface is fixed, bring the time derivative inside:

∫∫_S (∇ × E) · dS = ∫∫_S (-∂B/∂t) · dS

This holds for any surface S, so the integrands must be equal:

∇ × E = -∂B/∂t

This is the differential form of Faraday's law. The curl of the electric field equals the negative rate of change of the magnetic field.

Stokes' Theorem connects the integral form (experimentally observed) to the differential form (Maxwell's equation).

Applications: Ampère's Law

Ampère's law (in magnetostatics):

∫C B · dr = μ₀I{enclosed}

The circulation of the magnetic field around a loop equals the current through the loop (up to μ₀).

Using Stokes':

∫∫S (∇ × B) · dS = μ₀I{enclosed}

If the current density is J, then I_{enclosed} = ∫∫_S J · dS.

So:

∫∫_S (∇ × B) · dS = μ₀ ∫∫_S J · dS

Again, this holds for any surface, so:

∇ × B = μ₀J

This is the magnetostatic form of Ampère's law (ignoring the displacement current). The curl of the magnetic field equals the current density.

Stokes' connects the integral form to the differential form.

Proof Sketch

For a flat surface in the xy-plane, Stokes' reduces to Green's Theorem (already proved).

For a general surface, approximate it with tiny flat patches. Apply Green's to each patch. Sum over all patches. Interior edges cancel, leaving only the outer boundary. In the limit, you get Stokes'.

The proof involves parameterizing the surface, computing tangent vectors, cross products, and carefully tracking orientations. It's technical but conceptually straightforward: it's Green's Theorem applied locally and summed.

Relationship to the Divergence Theorem

Stokes' Theorem: ∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS = ∫_C F · dr (boundary is a curve)

Divergence Theorem: ∫∫∫_V (∇ · F) dV = ∫∫_S F · dS (boundary is a surface)

Both theorems connect an integral of a del operation over a region to an integral over the boundary. Stokes' handles curl and surfaces. Divergence handles divergence and volumes.

Together with Green's Theorem (the 2D case), they form the trinity of fundamental theorems in vector calculus.

Stokes' in Differential Geometry

In differential geometry, Stokes' Theorem is formulated using differential forms:

∫M dω = ∫{∂M} ω

where ω is a differential form, dω is its exterior derivative, M is a manifold, and ∂M is its boundary.

This unifies the fundamental theorem of calculus, Green's Theorem, Stokes' Theorem, and the Divergence Theorem into one statement. They're all special cases of the generalized Stokes' Theorem.

But for classical vector calculus in R³, the version we've discussed is the relevant one.

Computational Strategy

When should you use Stokes' Theorem?

Line integral looks hard, surface integral of curl looks easier: Convert to a surface integral. Choose the simplest surface with the given boundary.

Surface integral looks hard, line integral looks easier: Convert to a line integral. This is less common but occasionally useful.

Check if a field is conservative: If ∇ × F = 0, circulation around any loop is zero. The field is conservative.

Verify Faraday's or Ampère's law: Stokes' connects the integral and differential forms.

Why Stokes' Theorem Matters

Stokes' Theorem is the fundamental theorem for curl. It reveals that:

- Curl is the source of circulation (local rotation integrates to boundary circulation)

- Surface integrals of curl are independent of the surface (only the boundary matters)

- Curl-free fields have zero circulation (conservative fields are gradients)

It's essential for:

- Electromagnetism (Faraday's law, Ampère's law)

- Fluid dynamics (Kelvin's theorem, vorticity dynamics)

- Differential geometry (connections, curvature, gauge theory)

And it's the 3D generalization of Green's Theorem, completing the picture of how del operations connect to boundary integrals.

Understanding Stokes' geometrically—why boundary circulation equals interior curl, why the surface doesn't matter—is key to understanding the unity of vector calculus. It's not just a computational tool. It's a fundamental statement about the structure of space and fields.

Next, we'll cover the Divergence Theorem, which does for divergence what Stokes' does for curl. After that, we'll see how all three theorems unify in Maxwell's equations.

Part 9 of the Vector Calculus series.

Previous: Green's Theorem: Relating Line and Double Integrals Next: The Divergence Theorem: From Surface Flux to Volume Sources

Comments ()