Subsets and Supersets: When One Set Lives Inside Another

Every integer is a rational number. Every rational is a real. Every real is a complex.

That's not just a fact about numbers — it's a statement about sets living inside each other. The integers ℤ are a subset of the rationals ℚ. The rationals are a subset of the reals ℝ. Each set is contained in the next.

A ⊆ B means every element of A is also an element of B.

That's the unlock. Subsets describe containment. When you say "all dogs are mammals," you're saying the set of dogs is a subset of the set of mammals. The containment relation is one of the most fundamental in mathematics.

The Definition

A is a subset of B, written A ⊆ B, if:

Every element of A is also an element of B.

Formally: for all x, if x ∈ A, then x ∈ B.

Examples:

- {1, 2} ⊆ {1, 2, 3, 4} ✓

- {1, 5} ⊆ {1, 2, 3, 4} ✗ (because 5 ∈ {1, 5} but 5 ∉ {1, 2, 3, 4})

- {a, b} ⊆ {a, b} ✓ (every set is a subset of itself)

Every Set Is a Subset of Itself

A ⊆ A is always true.

Every element of A is in A. Trivially satisfied.

This might feel like cheating, but it's consistent with the definition. The subset relation includes equality as a possibility.

The Empty Set Is a Subset of Everything

∅ ⊆ A for any set A.

This is vacuously true. The definition says: "for all x, if x ∈ ∅, then x ∈ A." Since nothing is in ∅, there's no x to check. The statement holds by default.

Think of it this way: can you find an element of ∅ that isn't in A? No — because ∅ has no elements. So the condition can't be violated.

Proper Subsets

A is a proper subset of B, written A ⊂ B (or A ⊊ B), if:

- A ⊆ B, and

- A ≠ B

A proper subset is strictly smaller. It's contained in B but doesn't equal B.

{1, 2} ⊂ {1, 2, 3} — proper subset (missing the 3) {1, 2, 3} ⊂ {1, 2, 3} — false (they're equal, not proper)

Supersets

B is a superset of A, written B ⊇ A, if A ⊆ B.

It's just the subset relation from the other direction.

{1, 2, 3, 4} ⊇ {1, 2}

"Contains" and "is contained in" — two ways of saying the same relationship.

Proving Subset Relations

To prove A ⊆ B:

- Let x be an arbitrary element of A

- Show that x must be in B

- Conclude A ⊆ B

Example: Prove {x ∈ ℤ : x is divisible by 6} ⊆ {x ∈ ℤ : x is divisible by 3}.

Let n be divisible by 6. Then n = 6k for some integer k. So n = 3(2k), which means n is divisible by 3. Therefore n is in the second set. ∎

Proving Set Equality via Subsets

To prove A = B:

- Prove A ⊆ B

- Prove B ⊆ A

- Conclude A = B

This is the standard technique. Two sets are equal if and only if each is a subset of the other.

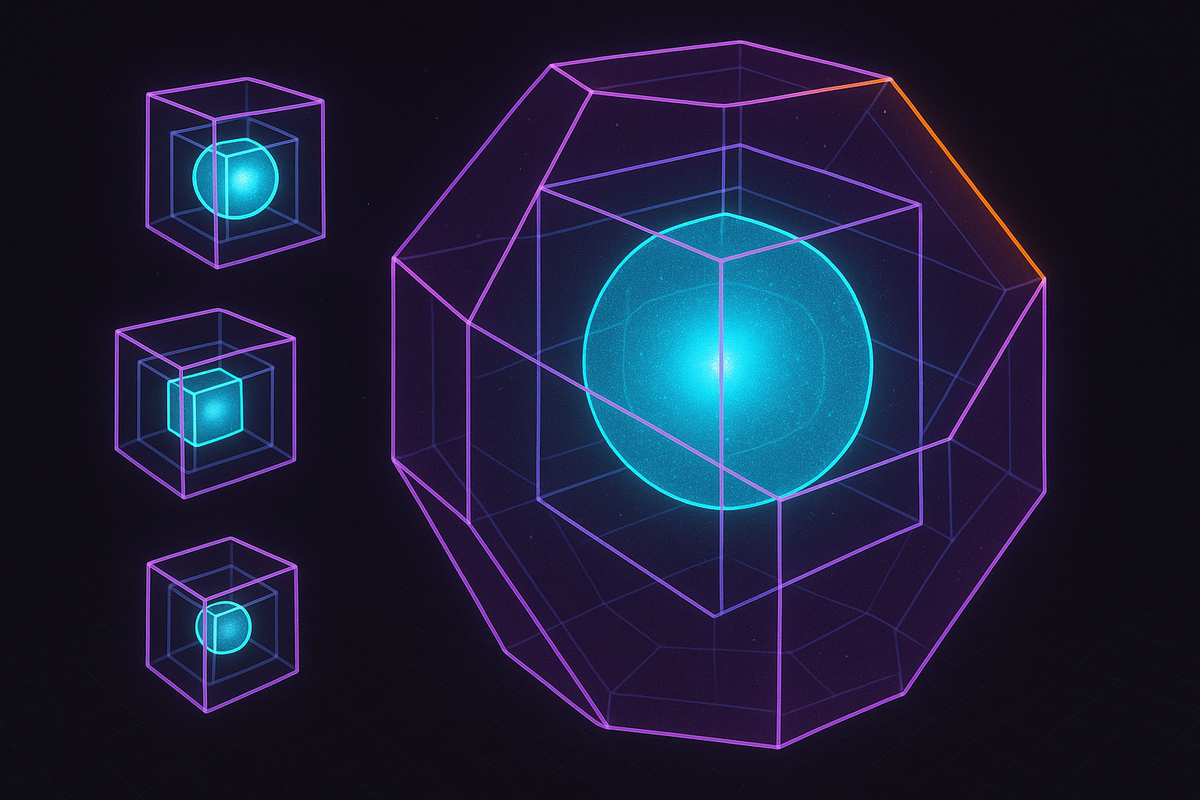

The Subset Lattice

For a given set S, the subsets form a structure called a lattice ordered by ⊆.

If S = {a, b}:

{a, b}

/ \

{a} {b}

\ /

∅

Moving up means adding elements. Moving down means removing them. ∅ is at the bottom; S is at the top.

Number Set Hierarchy

The standard number sets nest inside each other:

ℕ ⊆ ℤ ⊆ ℚ ⊆ ℝ ⊆ ℂ

- Natural numbers ⊆ integers (adding negatives)

- Integers ⊆ rationals (adding fractions)

- Rationals ⊆ reals (adding irrationals like √2, π)

- Reals ⊆ complex (adding imaginary numbers)

Each extension solves equations the previous set couldn't:

- ℤ: x + 3 = 0 (needs negatives)

- ℚ: 2x = 1 (needs fractions)

- ℝ: x² = 2 (needs irrationals)

- ℂ: x² = -1 (needs i)

Subsets vs. Elements

Don't confuse ∈ and ⊆.

- 3 ∈ {1, 2, 3} — 3 is an element of the set

- {3} ⊆ {1, 2, 3} — {3} is a subset of the set

The element 3 and the set {3} are different things. One is a number; the other is a set containing that number.

{3} ∈ {1, 2, 3}? No. The elements of {1, 2, 3} are the numbers 1, 2, and 3 — not the set {3}.

{3} ∈ {{1}, {2}, {3}}? Yes. Now {3} is an element of a set whose elements are sets.

How Many Subsets?

A set with n elements has exactly 2ⁿ subsets.

Why? For each element, you have two choices: include it or don't. That's 2 × 2 × ... × 2 = 2ⁿ possibilities.

{a, b} has 2² = 4 subsets: ∅, {a}, {b}, {a, b} {a, b, c} has 2³ = 8 subsets. A set with 10 elements has 1,024 subsets.

The set of all subsets is called the power set, written 𝒫(A).

Subset Relations Are Transitive

If A ⊆ B and B ⊆ C, then A ⊆ C.

Proof: Let x ∈ A. Since A ⊆ B, x ∈ B. Since B ⊆ C, x ∈ C. So x ∈ A implies x ∈ C. ∎

This is why the number hierarchy works: ℕ ⊆ ℤ and ℤ ⊆ ℚ implies ℕ ⊆ ℚ.

The Core Insight

Subsets formalize "all of these are also those."

When you say "every prime greater than 2 is odd," you're asserting a subset relation: {primes > 2} ⊆ {odd numbers}. When you classify objects into categories, you're mapping subsets.

The subset relation ⊆ is to sets what ≤ is to numbers — a way of ordering things by containment rather than size. And just as ≤ structures the number line, ⊆ structures the universe of sets.

Part 3 of the Set Theory series.

Previous: Set Notation: The Symbols That Define Collections Next: Union and Intersection: Combining Sets

Comments ()