Surface Integrals: Integrating Over Surfaces

Surface integrals let you sum a vector field over a 2D surface embedded in 3D space. They answer the question: "How much of this field passes through this surface?"

The canonical application is flux. If F is a vector field (velocity, electric field, whatever) and S is a surface, the surface integral ∫∫_S F · dS measures the total flow of F through S. How much fluid crosses the surface per unit time. How much electric field penetrates a closed shell. How much heat flows through a boundary.

Line integrals sum along curves. Surface integrals sum over surfaces. This is the next dimension up in integration: from 1D paths to 2D manifolds in 3D space.

The Setup

You have a vector field F(x, y, z) and a surface S parameterized by r(u, v) = (x(u, v), y(u, v), z(u, v)) for (u, v) in some region D.

The parameterization describes the surface as a function of two parameters u and v. As (u, v) varies over D, r(u, v) traces out the surface S.

Examples:

- A sphere of radius a: r(θ, φ) = (a sin φ cos θ, a sin φ sin θ, a cos φ)

- A plane z = c: r(u, v) = (u, v, c)

- A cylinder: r(θ, z) = (a cos θ, a sin θ, z)

The surface integral of F over S is:

∫∫_S F · dS = ∫∫_D F(r(u, v)) · (r_u × r_v) du dv

Let's break this down:

- r_u and r_v are the partial derivatives of r with respect to u and v. They're tangent vectors to the surface—one in the u-direction, one in the v-direction.

- r_u × r_v is the cross product of these tangent vectors. It's perpendicular to the surface (the normal vector) and has magnitude equal to the area of the infinitesimal parallelogram spanned by r_u and r_v.

- F(r(u, v)) is the field evaluated at the point on the surface.

- F · (r_u × r_v) is the dot product. It projects the field onto the normal direction. Only the component of F perpendicular to the surface contributes. Tangential components don't cross through—they slide along the surface.

- ∫∫_D ... du dv is a double integral over the parameter domain D. You're summing contributions from every infinitesimal patch of the surface.

The result is a single number: the total flux of F through S.

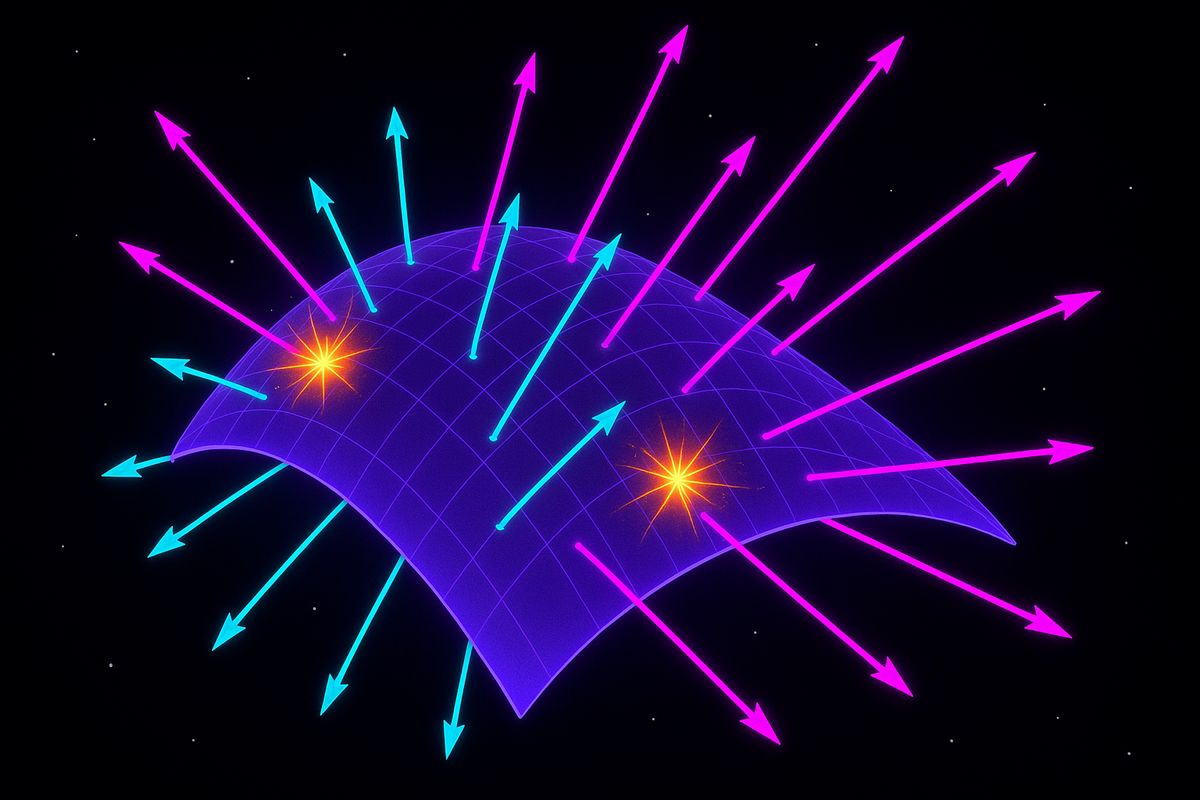

The Geometric Picture

Imagine the surface as a mesh. Each tiny patch has an area and a normal direction. The flux through that patch is (field component perpendicular to surface) × (patch area).

If the field points out of the surface, flux is positive. If it points in, flux is negative. If it's parallel to the surface, flux is zero—nothing crosses.

You sum flux over all patches. That's the surface integral.

For a velocity field, this is the volume flow rate. For an electric field, it's the electric flux (Gauss's law uses this). For a heat flux field, it's the total heat transfer.

The Normal Vector and Orientation

The cross product r_u × r_v gives a normal vector, but it can point in either direction depending on the order of u and v. Reversing the order reverses the normal.

For open surfaces, you choose an orientation (which side is "positive"). For closed surfaces, the convention is to use the outward-pointing normal.

The flux depends on orientation. Flipping the normal flips the sign of the flux:

∫∫S F · dS = -∫∫{-S} F · dS

where -S denotes the surface with reversed orientation.

This matters physically. If you're measuring flow out of a region, you use the outward normal. If you're measuring flow into a region, you use the inward normal (or take the negative of the outward flux).

Computing Surface Integrals: Example

Let F(x, y, z) = (0, 0, z), a field pointing upward with strength proportional to height.

Let S be the top hemisphere of the unit sphere: x² + y² + z² = 1, z ≥ 0.

Parameterize using spherical coordinates: r(θ, φ) = (sin φ cos θ, sin φ sin θ, cos φ) for θ in [0, 2π], φ in [0, π/2].

Compute the tangent vectors: r_θ = (-sin φ sin θ, sin φ cos θ, 0) r_φ = (cos φ cos θ, cos φ sin θ, -sin φ)

Cross product: r_θ × r_φ = (sin² φ cos θ, sin² φ sin θ, sin φ cos φ)

(After some vector algebra. The magnitude is sin φ, and the direction is outward radial.)

Evaluate F on the surface: F(r(θ, φ)) = (0, 0, cos φ)

Dot product: F · (r_θ × r_φ) = (0, 0, cos φ) · (sin² φ cos θ, sin² φ sin θ, sin φ cos φ) = sin φ cos² φ

Integrate: ∫∫_S F · dS = ∫_0^{2π} ∫_0^{π/2} sin φ cos² φ dφ dθ

The θ integral gives 2π. The φ integral: ∫_0^{π/2} sin φ cos² φ dφ = [-cos³ φ / 3]_0^{π/2} = 1/3

Total flux: 2π · (1/3) = 2π/3.

This is the flux of the field F through the hemisphere. The field points upward, the surface is curved upward, and flux is positive.

Flux Through Closed Surfaces

For a closed surface (like a sphere, a cube, a torus), the surface integral measures net flux out of the enclosed volume.

If ∫∫_S F · dS > 0, more field flows out than in. The interior contains sources.

If ∫∫_S F · dS < 0, more field flows in than out. The interior contains sinks.

If ∫∫_S F · dS = 0, inflow equals outflow. No net sources or sinks.

This is the conceptual foundation for the Divergence Theorem, which relates surface integrals over closed surfaces to volume integrals of divergence.

For incompressible fluid flow (∇ · F = 0), flux through any closed surface is zero. What flows in must flow out.

For electric fields around charges (∇ · E = ρ/ε₀), flux through a closed surface equals the enclosed charge. That's Gauss's law.

Scalar Surface Integrals

So far, we've discussed vector surface integrals: ∫∫_S F · dS, where F is a vector field.

There's also the scalar surface integral: ∫∫_S f dS, where f is a scalar function and dS is the surface area element.

This measures the integral of a scalar field over the surface. Applications include:

- Mass of a surface with variable density: ∫∫_S ρ dS

- Surface area: ∫∫_S 1 dS

- Average temperature over a surface: (1/Area) ∫∫_S T dS

The formula is:

∫∫_S f dS = ∫∫_D f(r(u, v)) |r_u × r_v| du dv

Same as before, but no dot product. You're just summing f weighted by surface area, not projecting a vector field.

Both types are called "surface integrals," which can be confusing. The vector version (flux) is more common in physics. The scalar version appears when integrating density or other scalar quantities over surfaces.

Surfaces Defined Implicitly

Sometimes surfaces are given implicitly as level sets: g(x, y, z) = c.

For example, a sphere is x² + y² + z² = 1. A plane is ax + by + cz = d.

For implicit surfaces, the normal vector is ∇g (the gradient of the defining function). This is perpendicular to the level set.

If the surface is z = f(x, y) (an explicit function), you can parameterize as r(x, y) = (x, y, f(x, y)).

Then: r_x = (1, 0, f_x) r_y = (0, 1, f_y) r_x × r_y = (-f_x, -f_y, 1)

And the surface integral becomes:

∫∫_S F · dS = ∫∫_D (F · (-f_x, -f_y, 1)) dx dy

This is a convenient form when the surface is given as a graph z = f(x, y).

Parameterization Independence

Like line integrals, surface integrals are independent of parameterization (as long as orientation is preserved).

You can parameterize the same surface in many ways. The surface integral will be the same, because the geometric object (surface + field + orientation) is fixed.

Different parameterizations change r_u × r_v, but the physical flux through the surface doesn't change.

This is important conceptually: surface integrals are geometric. They depend on the surface and the field, not on how you choose to describe the surface.

Applications: Gauss's Law

Gauss's law in electrostatics says:

∫∫S E · dS = Q{enclosed} / ε₀

where E is the electric field, S is a closed surface, and Q_{enclosed} is the total charge inside.

This is a surface integral. The flux of the electric field through a closed surface equals the charge inside (up to a constant).

Why? Because electric charge creates diverging electric field. The divergence theorem connects the surface integral (flux out) to the volume integral of divergence (sources inside). For electric fields, ∇ · E = ρ/ε₀, where ρ is charge density.

Gauss's law is useful for calculating electric fields when there's symmetry. If you have a spherically symmetric charge distribution, use a spherical Gaussian surface, and symmetry makes the surface integral trivial.

Applications: Fluid Flow

For an incompressible fluid, ∇ · v = 0 (divergence-free velocity field).

The surface integral ∫∫_S v · dS through any closed surface is zero. Inflow equals outflow.

For compressible fluids or fluids with sources/sinks, the flux through a closed surface equals the rate of volume creation inside:

∫∫_S v · dS = ∫∫∫_V (∇ · v) dV

This is the divergence theorem, which we'll cover in detail later. The point here is that surface integrals of velocity measure volume flow rate—a fundamental quantity in fluid dynamics.

Stokes' Theorem Preview

Just as line integrals around closed curves relate to curl via Green's Theorem, surface integrals relate to curl via Stokes' Theorem.

Stokes' Theorem says:

∫∫_S (∇ × F) · dS = ∫_C F · dr

where S is a surface, C is its boundary curve, and ∇ × F is the curl of F.

The surface integral of curl over S equals the line integral around the boundary. Local rotation sums to boundary circulation.

This is a 3D generalization of Green's Theorem. We'll explore it fully later, but the key point is that surface integrals of curl are connected to line integrals—another instance of a fundamental theorem relating integration and differentiation.

Coordinate Systems

Surface integrals can be computed in different coordinate systems.

Spherical coordinates are natural for spheres. The surface element on a sphere of radius a is:

dS = a² sin φ dθ dφ

Cylindrical coordinates are natural for cylinders. The surface element on a cylinder of radius a is:

dS = a dθ dz

Cartesian coordinates work when the surface is a graph z = f(x, y).

Choosing the right coordinate system simplifies computation. A sphere is a nightmare in Cartesian coordinates but trivial in spherical coordinates.

The Divergence Theorem Connection

For closed surfaces, surface integrals are intimately connected to volume integrals via the Divergence Theorem:

∫∫_S F · dS = ∫∫∫_V (∇ · F) dV

The flux through the surface equals the integral of divergence in the volume.

Divergence measures "spreading" at each point. Summing divergence over a volume tells you the net spreading. But net spreading is also the flux out of the boundary. The two are equal.

This theorem is fundamental. It transforms surface integrals (hard to compute) into volume integrals (often easier), or vice versa. It also reveals conservation laws and connects local properties (divergence at a point) to global properties (flux through a surface).

Computational Tips

When computing surface integrals:

- Parameterize the surface: Choose r(u, v) that makes the geometry clear. Use symmetry.

- Compute tangent vectors: r_u and r_v. These are partial derivatives.

- Cross product: r_u × r_v gives the normal vector. Check that it points in the correct direction (outward for closed surfaces).

- Evaluate the field: Substitute r(u, v) into F to get F(r(u, v)).

- Dot product: Compute F · (r_u × r_v). Simplify as much as possible.

- Integrate: ∫∫_D (result from step 5) du dv over the parameter domain.

If the surface has symmetry and the field respects that symmetry, the integral can simplify dramatically. Exploit symmetry whenever possible.

Why Surface Integrals Matter

Surface integrals extend integration from 1D (intervals) and 2D (regions in the plane) to 2D surfaces embedded in 3D space. They let you measure flux, flow, and field penetration through boundaries.

They're essential for:

- Gauss's law in electromagnetism

- Fluid dynamics (flow through surfaces)

- Heat transfer (energy flux through boundaries)

- The Divergence Theorem (relating surface and volume integrals)

- Stokes' Theorem (relating surface integrals and line integrals)

Without surface integrals, you can't formulate the fundamental conservation laws of physics. Flux is a fundamental concept, and surface integrals are how you calculate it.

Understanding surface integrals—both computationally and geometrically—is necessary for the Divergence Theorem and Stokes' Theorem, which are the capstones of vector calculus. Those theorems only make sense once you understand what surface integrals are measuring.

Next, we'll turn to the differential operators—divergence, curl, and the gradient—that appear inside the integrals in the fundamental theorems. These operators describe local properties of vector fields. The theorems connect those local properties to global integrals.

Part 4 of the Vector Calculus series.

Previous: Line Integrals: Integrating Along Curves Next: Divergence: How Much Does a Field Spread Out?

Comments ()