Synchron: The Less Invasive Competitor

Here's a question that keeps neurosurgeons up at night: what if we could put a device in someone's brain without actually cutting into their brain?

Tom Oxley, a neurologist from Melbourne, thought about this problem for years. The obvious barrier to brain-computer interfaces wasn't the electronics or the algorithms—it was the surgery. You had to drill through the skull. Open the protective membranes. Push electrodes into brain tissue. Every step carried risk: infection, bleeding, damage to nearby structures.

Most people, even those with severe disabilities, were unwilling to accept those risks for an experimental technology. The surgery was the bottleneck.

What if you could deliver the device through the blood vessels instead?

The brain is fed by blood vessels that branch and narrow as they penetrate deeper. Cardiologists have been threading devices through blood vessels for decades—stents, catheters, pacemaker leads. Why not use the same approach to reach the brain?

Oxley founded Synchron to find out. And the device they built—the stentrode—is the most serious competitor to Neuralink's approach.

The Stentrode: Brain Implant via Blood Vessel

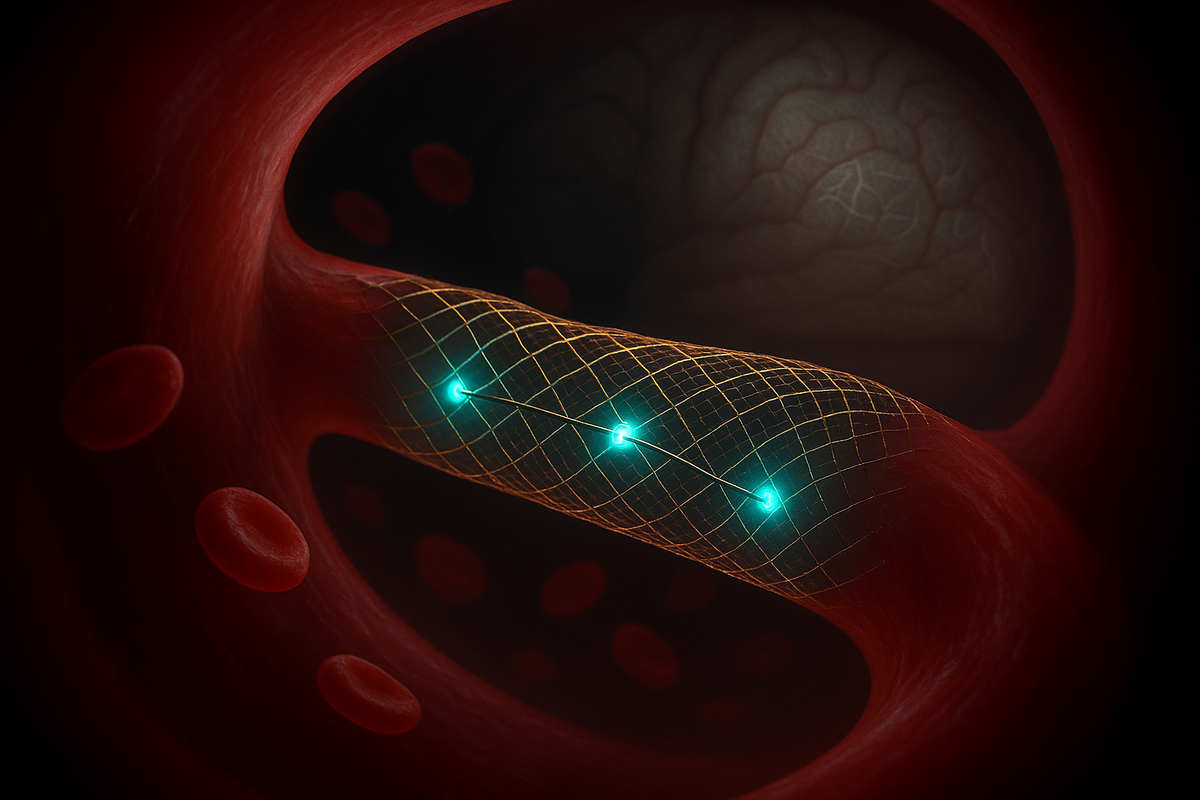

The stentrode looks nothing like traditional brain electrodes. It's a small mesh tube, about the size of a matchstick, embedded with 16 electrodes. Think of a tiny fishing net made of wire.

Here's how it's implanted:

A surgeon makes a small incision in the neck and accesses the jugular vein. They thread a catheter up through the vein, into the brain's venous system, until it reaches a blood vessel that runs next to the motor cortex. Then they deploy the stentrode.

The mesh expands and lodges against the inner wall of the blood vessel. The electrodes press against the vessel wall, close to the motor cortex tissue on the other side. Over time, the vessel wall grows around the mesh, integrating it.

No drilling through the skull. No opening the protective membranes. No penetrating brain tissue directly. The surgery takes about two hours and patients go home the same day.

You're putting a brain implant in through the neck. That's wild.

The Tradeoff

The obvious question: if you're recording through a blood vessel wall, at a distance from the neurons, don't you lose signal quality?

Yes. Significantly.

Neuralink's N1 has 1,024 electrodes in direct contact with brain tissue. The stentrode has 16 electrodes recording through the vessel wall. The signal-to-noise ratio is much lower. Individual neurons can't be distinguished—you're recording aggregate activity from populations of cells.

This is a fundamental tradeoff. Neuralink's approach: high resolution, high risk. Synchron's approach: low resolution, low risk.

The question is whether the stentrode's resolution is good enough. For some applications, it appears to be.

Synchron's patients can control computers. They can move a cursor. They can send text messages and emails. They can browse the web. Philip O'Keefe, one of their Australian patients with ALS, sent what's believed to be the first tweet composed directly from brain signals in 2021.

They're not getting the fine-grained control that Neuralink's high electrode count enables. They're not decoding individual finger movements or playing Mario Kart with precision. But for basic computer control, basic communication, basic digital independence—the stentrode works.

The best technology isn't always the most powerful. Sometimes it's the one people will actually use.

The Patients

Synchron started human trials in Australia in 2019, before Neuralink had implanted anyone. Their early patients have been living with stentrodes for years now, providing crucial long-term data.

Philip O'Keefe was diagnosed with ALS (Lou Gehrig's disease) in 2015. By 2020, he was almost completely paralyzed. He received a stentrode implant in April 2020 and has been using it to control computers ever since.

His description of the experience: "I just think about the movement I want, and it happens on the screen."

The training period was about three months. O'Keefe learned to generate consistent brain signals for different actions—thinking about movement in different ways produced different signals, which the system learned to map to different commands.

He sends texts to his wife. He shops online. He manages his banking. He stays connected to the world in ways that would otherwise require constant assistance.

Graham Felstead, another Australian patient, was implanted in 2019—making him one of the longest-running BCI users in the world. Years later, his stentrode is still working. This kind of durability data is exactly what the field needs.

These aren't just test subjects. They're pioneers who can now text their families.

The US Expansion

In 2022, Synchron received FDA approval to begin human trials in the United States. Their first US patient was implanted in July 2022 at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

This matters for the competitive landscape. Neuralink got massive attention when they announced human trials, but Synchron had been implanting patients for years already. They have more human data, even if Neuralink has more electrodes.

Synchron has also received significant investment—including from Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates. The market recognizes that there may be room for multiple approaches, or that the less invasive option might win in the long run.

The company is now running trials at multiple US sites and expanding their patient population. Each patient provides more data on safety, durability, and usability.

The Technical Details

Let's get specific about how the stentrode actually works.

Electrode placement. The stentrode lodges in the superior sagittal sinus, a large vein that runs along the top of the brain, near the motor cortex. The electrodes are positioned to record from the precentral gyrus—the strip of cortex that controls voluntary movement.

Signal processing. Because the signals are weaker and noisier than direct recordings, Synchron uses machine learning to decode movement intent from the aggregate neural activity. The system learns each patient's unique signal patterns and maps them to commands.

Command set. Current patients can generate about 16-20 distinct commands—enough for basic computer control but not complex manipulation. This is the resolution ceiling imposed by the limited electrode count and indirect recording.

Wireless transmission. Like Neuralink, the stentrode is wireless. A small device implanted in the chest (similar to a pacemaker) receives signals from the stentrode and transmits them to an external computer for processing.

Durability. The stentrode integrates with the blood vessel wall over months. Unlike electrodes that penetrate brain tissue, it doesn't trigger the same immune response. This may give it longevity advantages—early data suggests the signals remain stable over years.

The Regulatory Advantage

Here's something the headlines often miss: Synchron has a regulatory head start.

FDA approval for medical devices is hard. You need extensive safety data. You need to demonstrate that the device does what you claim. You need to navigate a complex bureaucratic process.

Synchron has been accumulating this data for years. Their Australian trials provided the foundation. Their US trials are extending it. By the time Neuralink finishes their early trials, Synchron may be further along the path to broader approval.

This matters because the first company to get FDA approval for a consumer-ready BCI will have an enormous advantage. They'll be able to market to patients, train surgeons, build infrastructure—while competitors are still in trials.

The race isn't just about technology. It's about regulatory positioning. And Synchron has a lead.

The Limitations

Let's be clear about what the stentrode can't do.

High-resolution control. If you want to decode individual finger movements, play complex video games, or control a robotic arm with precision, the stentrode's 16 electrodes aren't enough. This is fundamentally a limitation of the indirect recording approach.

Bidirectional communication. The stentrode is read-only—it records from the brain but doesn't stimulate. You can't create sensory feedback through it. More advanced applications (feeling through a prosthetic limb, for instance) require technology that the stentrode doesn't provide.

Cognitive enhancement. Any vision of BCIs for healthy people—enhancing memory, accelerating learning, connecting to AI—would require much higher resolution than the stentrode offers. This is a device for restoring basic function, not augmenting it.

Universal applicability. The stentrode is designed for a specific blood vessel position near the motor cortex. Different applications (visual prosthetics, speech decoding, mood modulation) would require different placements or different devices entirely.

None of these are criticisms—every technology has limits. The question is whether those limits are acceptable for the intended use case.

For basic computer control by paralyzed patients, the stentrode appears to be good enough. That's not a small thing.

The Business Case

Synchron's pitch to investors goes something like this:

Brain-computer interfaces will become a major medical market. Tens of millions of people worldwide have conditions that could benefit—paralysis, ALS, locked-in syndrome, severe stroke. Even a fraction of that market represents billions of dollars.

But market size depends on adoption, and adoption depends on risk tolerance. Most people won't accept a 1% risk of serious complication for an experimental device. They might accept a 0.1% risk. Or a 0.01% risk.

The stentrode's less invasive approach could dramatically expand the pool of people willing to try BCIs. Lower risk means more patients. More patients means more data. More data means faster iteration. Faster iteration means better technology.

And there's another angle: if the stentrode proves safe and effective enough, it might not need to compete with Neuralink at all. Different patients might choose different devices based on their specific needs and risk tolerance. A person with ALS who mainly wants to send emails might prefer the stentrode. A person with tetraplegia who wants to play competitive video games might prefer Neuralink.

Multiple technologies can succeed in the same market. Especially one this large.

What to Watch

Synchron's progress will be measured by several key indicators:

Trial results. How are US patients doing? What's the complication rate? How long do the devices remain functional?

Regulatory milestones. When do they move from investigational trials to broader approval? What indications are approved first?

Technical improvements. Can they increase electrode count while maintaining the minimally invasive approach? Can they add stimulation capabilities for bidirectional communication?

Market adoption. If/when approved, how many patients choose the stentrode? What's the training success rate? What are the outcomes?

The stentrode represents a bet that good enough, delivered safely, at scale, beats optimal, delivered riskily, to a few. That's a reasonable bet. We'll know within a few years whether it pays off.

Why Synchron Matters

Philip O'Keefe doesn't care that his device has 16 electrodes instead of 1,024. He cares that he can text his wife.

The ALS patients in Synchron's trials are on a timeline. Their disease is progressive. A device that works now, even if not optimal, is worth more than a theoretical perfect device that might arrive too late.

The technology is the means. Independence is the end.

Synchron proves something important: there's more than one path to working brain-computer interfaces. A device that's 95% as good but implantable with a two-hour outpatient procedure might reach far more patients than one requiring open brain surgery.

The blood vessel approach that seemed like a workaround might turn out to be the mainstream path. Or a stepping stone to something else entirely.

Either way, the patients are better off for having the option.

The brain isn't just accessible from outside. It's accessible from within—through the rivers of blood that keep it alive.

Comments ()