Joseph Tainter: Diminishing Returns on Complexity

In the late Roman Empire, the government tried something desperate: it made occupations hereditary by law.

If your father was a baker, you were a baker. If your father was a soldier, you were a soldier. If your father was a tax collector, guess what—you were a tax collector. The state literally bound people to their jobs because it couldn't afford to let the workforce reorganize itself.

This wasn't tyranny for its own sake. It was desperation. The empire had become so complex, so expensive to maintain, that any disruption to the system threatened its survival. The cost of flexibility had become higher than the cost of rigidity. So they chose rigidity.

Joseph Tainter, an anthropologist who spent decades studying collapsed civilizations, saw this story and asked a question that would reshape how we understand collapse: What if this wasn't a failure of Roman governance? What if this was the inevitable result of success?

His answer became the most influential framework in collapse studies: societies collapse because they're good at solving problems.

Wait, what?

The Logic of Complexity

Here's Tainter's core insight, and it's counterintuitive enough that you should sit with it for a moment.

Societies face problems. Invasion. Famine. Disease. Conflict. Coordination failures. The successful societies are the ones that solve these problems. And how do they solve them? By adding complexity.

You need to defend your borders? Create a standing army with a hierarchy of officers, a logistics system, and training institutions. That's complexity. You need to manage water resources? Build an irrigation bureaucracy with engineers, administrators, and inspectors. Complexity. You need to settle disputes? Develop a legal system with judges, lawyers, and precedents. More complexity.

Each addition makes sense in the moment. You have a problem; complexity solves it. The society that can manage more complexity can solve more problems. This is adaptive. This is what winning looks like.

But—and here's where Tainter earns his place in the collapse literature—complexity has costs. Every bureaucrat needs a salary. Every soldier needs food and equipment. Every road needs maintenance. Every law needs enforcement. The complexity that solved your problems now requires resources to sustain.

And the relationship between complexity and returns isn't linear. It's a curve that bends.

The Curve That Dooms Civilizations

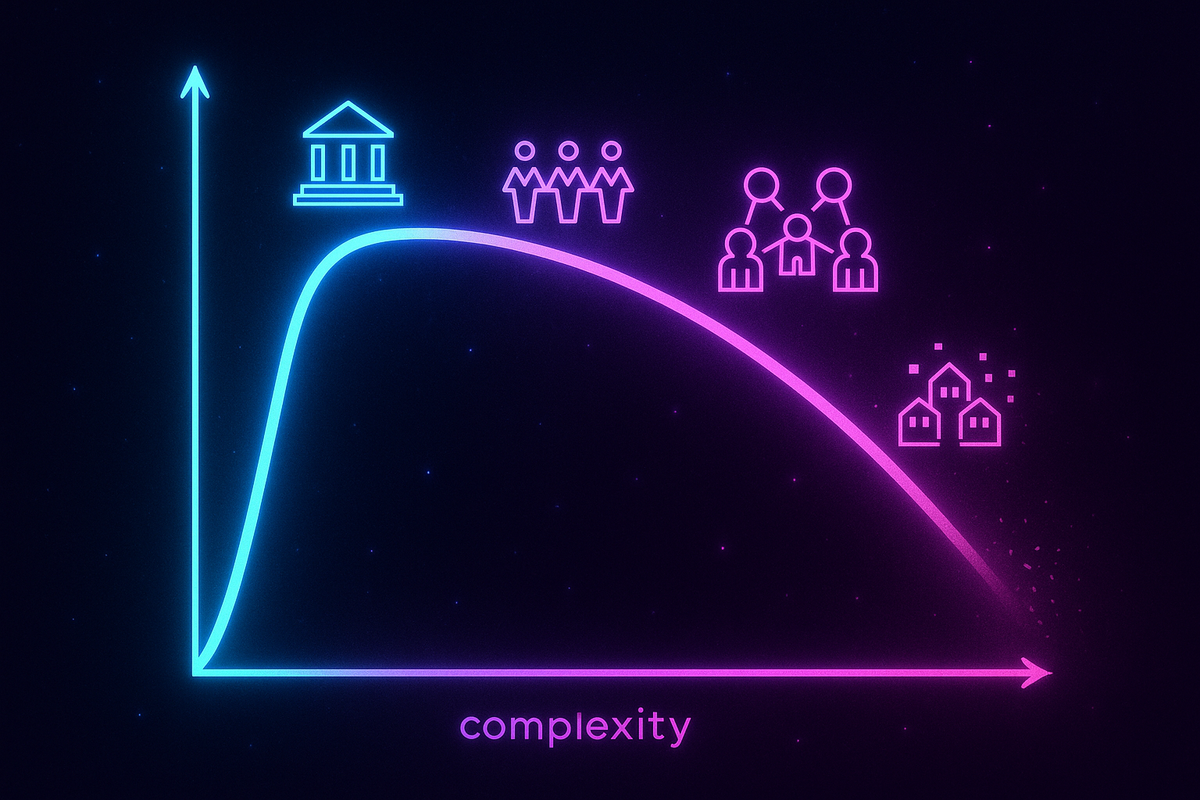

Imagine graphing this. X-axis is complexity: bureaucracy, specialization, hierarchy, infrastructure. Y-axis is benefits: security, prosperity, coordination, problem-solving capacity.

At the beginning, the curve rises steeply. Your first standing army is transformative. Your first writing system revolutionizes administration. Your first professional bureaucracy enables coordination at scale you couldn't previously imagine. High complexity, high returns.

But the curve bends. The tenth layer of bureaucracy helps less than the first. The hundredth regulation adds less benefit than the tenth. You're still gaining, but the gains are shrinking.

Then the curve flattens. More complexity yields almost nothing. You're spending resources to add administrative capacity that doesn't actually improve anything. But you keep adding because you don't know how to stop, because every problem still looks like it needs a complex solution, because the bureaucracy that allocates resources is itself part of the complexity and isn't going to vote to eliminate itself.

Then—and this is the part that gets people—the curve can decline. Past a certain point, more complexity makes things worse. The bureaucracies conflict with each other. The regulations contradict. The coordination costs exceed the coordination benefits. You're now paying to make your society less functional.

Tainter's argument is that Rome, the Maya, the Chacoans, and dozens of other collapsed societies weren't destroyed by external enemies or natural disasters. They were destroyed by the logic of their own success. They solved problems by adding complexity until the complexity cost more than it was worth.

How This Actually Worked in Rome

Let's trace it through the Roman case, because it's the one Tainter analyzed most thoroughly.

Early Rome was simple. Citizen-farmers who served as soldiers when needed. Minimal bureaucracy. Local governance. The complexity was low, but so were the problems it could solve.

As Rome expanded, it added complexity to manage its growth. Provincial governors to administer conquered territories. Tax systems to extract resources. Roads to move armies and goods. Legal frameworks to integrate diverse populations. Each addition made sense. Each addition enabled further expansion.

By the height of the empire in the second century AD, Rome had achieved complexity no previous society had matched. Professional bureaucracy spanning three continents. Legal system that influenced Western law for two millennia. Infrastructure—roads, aqueducts, harbors—that wouldn't be equaled for a thousand years. Standing army of hundreds of thousands. Grain distribution feeding a million people in the capital.

But complexity has costs, and by the third century, those costs were becoming visible.

The army, expanded to defend lengthening frontiers, consumed an ever-larger share of the budget. The bureaucracy, grown to manage the expanded empire, consumed its own share. Together they demanded tax revenues that exceeded what the economy could sustainably produce.

The government responded the only way it knew how: with more complexity. More tax collectors to extract more revenue. More administrators to manage the tax collectors. More soldiers to enforce the extraction. More bureaucracy to coordinate the soldiers.

Each addition was locally rational. Each addition made the problem worse at the system level. The empire was now spending resources to maintain complexity that wasn't delivering returns. The curve had bent past the peak.

The Trap Nobody Escapes

Here's the part of Tainter's analysis that should keep you awake at night: the trap is almost impossible to escape.

Why don't societies just... simplify? If complexity has diminishing returns, why not remove some complexity and pocket the savings?

Because complexity creates constituencies. Every bureaucracy employs people who don't want to lose their jobs. Every regulation benefits someone who will lobby to keep it. Every layer of hierarchy contains people whose status depends on that layer existing.

And because simplification looks like failure. The politician who says "we should have fewer programs, less regulation, smaller bureaucracy" is announcing that previous investments were wasted. Nobody wants to hear that. It's much easier to add a new program than to admit an old one didn't work.

And because the simple solutions have been foreclosed. Once you've built an elaborate irrigation bureaucracy, "just move to where water is more abundant" stops seeming like an option. The investment in the current approach precludes alternatives.

Tainter argues that societies don't choose collapse. They choose complexity. Collapse is what happens when the complexity they've chosen can no longer be sustained.

The Most Disturbing Implication

Ready for the part that really keeps people up?

Tainter argues that collapse can be economically rational. For ordinary people. In certain circumstances.

Think about it from the perspective of a peasant farmer in late Roman Britain. What does the empire provide you? Roads you don't travel. Legal rights you can't enforce. Military protection that increasingly fails to protect. And in exchange? Crushing taxes. Forced labor. Sons conscripted into armies that fight on frontiers you'll never see.

When the legions withdraw, when the empire contracts, when the complexity evaporates—what do you actually lose?

The taxes stop. The conscription stops. The forced labor stops. Yes, some services disappear. The roads degrade. The courts close. But those services weren't serving you anyway. You're arguably better off.

This is why collapses often happen without much resistance from ordinary people. The complexity that collapsed was elite complexity—serving elite interests, extracting from everyone else. When it goes, the people who were paying for it don't necessarily mourn.

The fall of Rome wasn't bad for all Romans. It was bad for the people whose positions depended on Roman complexity—the senators, the bureaucrats, the generals. For the peasant in the provinces, the simplified post-Roman world might have been... fine. Different. But fine.

The Problem-Solving Trap in Real Time

Let me make this concrete with an example that isn't Roman.

Consider airline security before and after 9/11. Before: walk through a metal detector, maybe get your bag x-rayed, board your flight. After: take off your shoes, remove your laptop, 3.4 ounces of liquids maximum, full-body scanners, TSA PreCheck (which costs money to avoid the security that supposedly keeps you safe), random secondary screening, no-fly lists, reinforced cockpit doors, air marshals.

Has this made flying safer? Probably somewhat, though the evidence is contested. Has it made flying dramatically more expensive and unpleasant? Definitely. The complexity was a response to a real problem. But the relationship between the complexity added and the safety gained is... unclear.

And here's the thing: none of it will ever be removed. Every security measure has become permanent. No politician will vote to reduce airline security, even if the measures demonstrably don't work, because if something goes wrong afterward, they'll be blamed. The complexity only accumulates.

Now multiply this across every domain. Healthcare. Education. Finance. Environmental regulation. Criminal justice. In each domain, problems arise. In each domain, complexity is the solution. In each domain, the complexity compounds.

Nobody is making a mistake. Each individual addition is defensible. The aggregate result is a society that spends ever-increasing resources on administration, compliance, and coordination—while the actual things being administered, complied with, and coordinated receive ever-decreasing shares of attention and funding.

The curve bends. We just don't notice because we're inside it.

What Tainter Got Wrong (Maybe)

Tainter's framework has been challenged on several fronts. Fair to address them.

Technology can change the curve. Tainter developed his framework in the 1980s, before the internet, before the dramatic reduction in information costs. Maybe digital infrastructure has increasing returns—maybe the marginal cost of coordination actually decreases with scale in ways that weren't true for physical bureaucracies. The complexity calculus for a society with Google might be different from the complexity calculus for a society with clay tablets.

Collapse isn't the only outcome. Some societies have simplified without catastrophic collapse. Byzantium, which we'll discuss later in this series, repeatedly shed complexity and survived. Japan has deliberately simplified at various points in its history. Collapse happens when simplification doesn't, but simplification is at least theoretically possible.

The framework is hard to operationalize. How do you actually measure complexity? How do you measure returns on complexity? The framework is compelling as a qualitative story, but turning it into quantitative predictions is difficult. We can tell the story after the fact, but can we identify where on the curve a society is before collapse?

External shocks matter. Tainter emphasizes internal dynamics, but Rome also faced climate changes, plague pandemics, and unusually intense barbarian pressure. Would Rome have collapsed without those shocks? Tainter would say yes—the internal dynamics made it inevitable. Critics argue the shocks were necessary, the internal dynamics just determined how bad the result would be.

These are real objections. Tainter's framework isn't the complete story. But nobody seriously argues it's not part of the story. The diminishing returns on complexity are real. The question is how much they explain.

The Contemporary Resonance

I've avoided contemporary applications until now, but let's be honest about why you're reading this.

Tainter's book was published in 1988. It keeps getting cited today because people see the pattern.

The Federal Register—the compendium of US federal regulations—ran 2,620 pages in 1936. Today it exceeds 90,000 pages. That's not 90,000 pages of wisdom. It's 90,000 pages of complexity, accumulated because nobody ever removes anything, because every problem gets addressed with more rules, because simplification is politically impossible even when everyone agrees the complexity has become counterproductive.

Healthcare administration consumes roughly 30% of healthcare spending in the US—not care, administration. We've built complexity to manage complexity to manage complexity, and somewhere in there we forgot we were supposed to be treating patients.

Higher education now requires students to spend four years and six figures to acquire credentials that employers increasingly find meaningless—but nobody can stop requiring, because everyone else requires them, because the system is locked in.

Is any of this news to you? Or does it just sound like... how things are?

The trap is that "how things are" is exactly what diminishing returns on complexity feels like from the inside. You don't notice the degradation because it's gradual. You don't notice the costs because they're distributed. You don't notice the absence of returns because you've normalized the current level of dysfunction.

Tainter would say: the curve bends the same way whether you notice or not.

The Coherence Connection

Through the lens of coherence theory—the framework this publication exists to explore—Tainter's insights get even sharper.

Complexity serves coherence, initially. Coordination mechanisms, shared institutions, common infrastructure—these increase the coherence of a society. They make the parts work together. They enable collective action at scale.

But excessive complexity can undermine coherence. When the rules contradict each other. When the bureaucracies work at cross purposes. When the coordination mechanisms require so much overhead that they prevent the coordination they were designed to enable.

A society can be highly complex and completely incoherent. The formal structures exist, but they don't actually integrate anything. The system runs hot—lots of activity, lots of energy consumption—while producing less and less actual coordination.

Collapse, in this view, is coherence failure. The system becomes too complex to cohere. It fragments because fragmentation—local coherence replacing failed global coherence—is the only option left.

The Western Roman Empire didn't fall because the pieces stopped existing. It fell because the pieces stopped functioning as a whole. The coherence that made Rome Rome evaporated. What remained was complexity without integration, structure without function.

Eventually, even the structure went.

Further Reading

- Tainter, J.A. (1988). The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press. - Tainter, J.A. (2006). "Social complexity and sustainability." Ecological Complexity. - Tainter, J.A. & Patzek, T.W. (2012). Drilling Down: The Gulf Oil Debacle and Our Energy Dilemma. Springer.

This is Part 2 of the Collapse Science series. Next: "Jared Diamond: Why Societies Choose to Fail."

Comments ()