Tarot: How 78 Cards Became a Mirror

In 1440s Milan, a duke commissioned a set of illustrated playing cards.

The Visconti-Sforza deck wasn't meant for divination. It was meant for games—specifically, a game called tarocchi, probably similar to modern bridge. The cards had four suits (cups, coins, swords, batons) plus a fifth suit of picture cards (the trump cards, or trionfi) featuring images like The Fool, The Emperor, The Wheel of Fortune.

Rich people played cards. Artists painted elaborate decks for rich people. Nobody was reading fortunes.

Three hundred years later, those same images had become the foundation of Western occultism. How?

The transformation of tarot from a card game to a divination system is a case study in how humans create meaning—how we take arbitrary symbols and project onto them until they seem to vibrate with cosmic significance.

The Occult Turn

In 1781, a French freemason named Antoine Court de Gébelin published a speculative essay claiming tarot cards were actually the remnants of ancient Egyptian wisdom. The book of Thoth, god of magic and writing, encoded in playing cards and smuggled through history by secretive initiates.

This was complete fantasy. There's no historical connection between tarot and ancient Egypt. Court de Gébelin made it up based on superficial symbolic associations and Enlightenment-era Egyptomania.

But it didn't matter. The idea caught on.

Within decades, fortune tellers were using tarot cards for divination. Occultists developed elaborate systems mapping the 22 trump cards (now called the "Major Arcana") onto the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet, the 22 paths of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, the 22-stage journey of spiritual development.

The symbols hadn't changed. The context had. Cards that once depicted Renaissance allegorical figures now represented universal archetypes. The Fool wasn't just a jester—he was the soul beginning its journey. The Wheel of Fortune wasn't just a common image—it was the cosmic cycle of karma.

The Rider-Waite Revolution

In 1909, Arthur Edward Waite commissioned artist Pamela Colman Smith to create a new tarot deck. The result—the Rider-Waite deck (named after publisher William Rider)—is now the most influential tarot deck in history.

What made it different? The Minor Arcana.

Previous decks showed the Minor Arcana (the four suits of numbered cards) as simple pip cards—three cups, seven swords, nine coins. Like a regular deck of playing cards, just with medieval imagery.

Pamela Colman Smith illustrated every card. The Three of Swords became a heart pierced by three blades. The Ten of Cups became a family gazing at a rainbow. The Five of Pentacles became two beggars in snow outside a church window.

Each card became a scene. And scenes invite interpretation.

Now when you drew the Five of Cups—which shows a figure in a black cloak contemplating three spilled cups while two full cups stand behind them—you had an image to work with. Loss. Grief. But also what remains. The visual detail created infinite interpretive angles.

The Rider-Waite deck made tarot readable in a way it hadn't been before. The imagery provided scaffolding for projection. And a century later, it remains the standard.

The Structure of the Deck

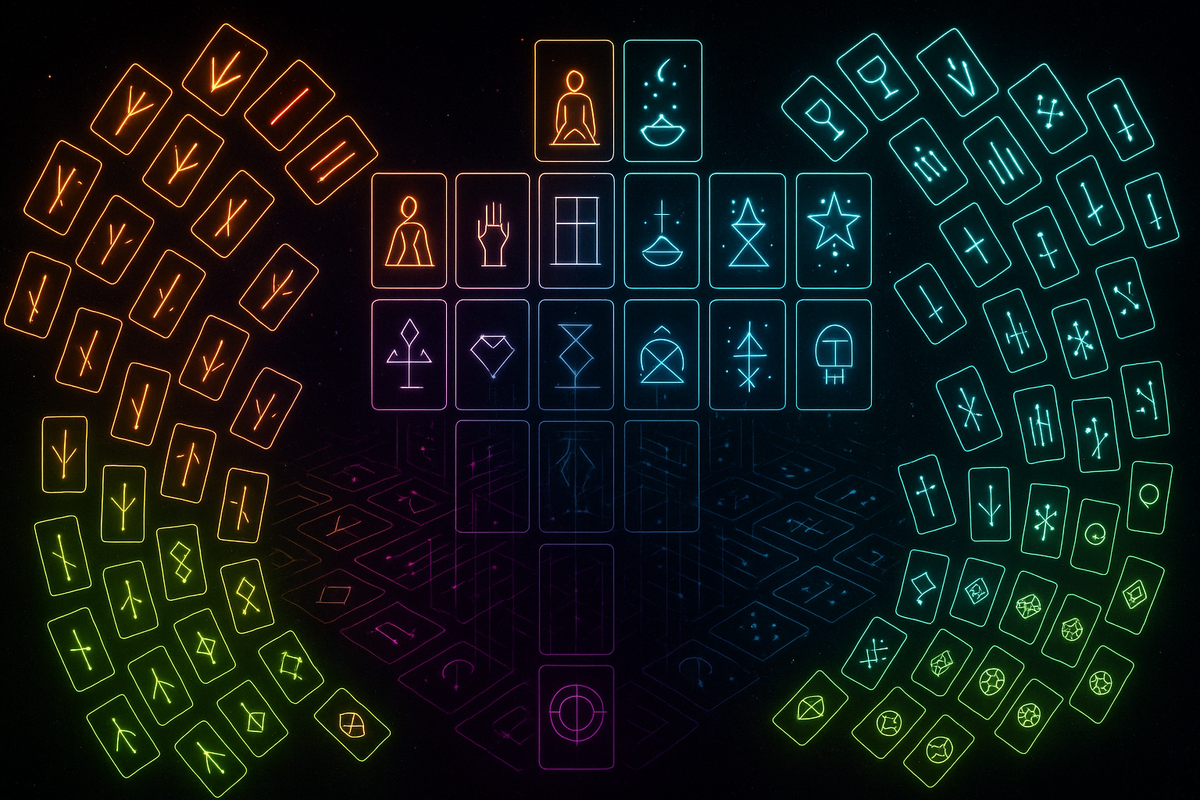

A tarot deck has 78 cards divided into two groups:

Major Arcana (22 cards): The Fool through The World, plus cards like The High Priestess, The Lovers, Death, The Tower. These represent archetypal forces, major life themes, spiritual principles.

Minor Arcana (56 cards): Four suits of 14 cards each. Wands (fire, creativity), Cups (water, emotion), Swords (air, intellect), Pentacles (earth, material world). Each suit runs Ace through Ten plus four court cards (Page, Knight, Queen, King).

The structure creates a layered meaning system: - Major Arcana: the big stuff, the soul journey, fate - Minor Arcana: the daily stuff, specific situations, practical matters - Suits: elemental domains (creative, emotional, mental, material) - Numbers: quantity and stage (ones are beginnings, tens are completions) - Court cards: personality types, people in your life

This is remarkably well-designed for divination purposes. You can do simple three-card draws or elaborate spreads. You can focus on Major Arcana for spiritual questions or Minor Arcana for practical ones. The system scales.

The Spread as Framework

You don't just draw cards at random. You lay them in a spread—a spatial arrangement where each position has a designated meaning.

The most famous spread is the Celtic Cross (ten cards): 1. The present situation 2. The challenge 3. The distant past 4. The recent past 5. The best possible outcome 6. The near future 7. Your attitude/approach 8. External influences 9. Hopes and fears 10. The final outcome

This is narrative scaffolding made explicit. The spread turns the card-drawing into a structured story: here's where you are, here's what shaped you, here's where you're going, here's what you can control, here's what you can't.

The spread doesn't require the cards to have meaning. It creates a framework, and then the cards—whatever they are—fill the slots. Your brain does the rest.

This is the genius of tarot as a divination system. The spread provides structure. The imagery provides raw material. The reader (you or someone else) provides the interpretive labor that connects the two.

The Archetypal Theory

Jung (again) provides the theoretical framework that makes tarot seem profound.

His concept of archetypes—universal patterns in the collective unconscious—maps neatly onto the Major Arcana. The Fool is the eternal innocent, the Holy Fool who knows nothing and thus can learn anything. The Magician is the archetype of creative will, the ability to manifest. The High Priestess is the unconscious, the hidden, the feminine mystery.

These aren't random images. They're images that resonate across cultures because they tap into deep psychological patterns. The Hero, the Shadow, the Wise Old Man, the Great Mother—these appear in myths worldwide, and they appear in tarot.

Whether or not archetypes are "real" in Jung's sense, the Major Arcana do function as projective surfaces for universal human concerns. Death, change, authority, love, fate, completion—the cards address themes everyone confronts.

This is why tarot feels meaningful even to skeptics. The imagery touches real psychological content. When you draw The Tower—a structure struck by lightning, figures falling—you don't need to believe in divination to feel something. The image resonates because catastrophic change is a human universal.

The Reading Dynamic

Watch an actual tarot reading and something interesting emerges.

The reader lays out cards. They narrate: "In the challenge position, you have the Three of Swords. This often represents heartbreak or painful truths. Does that resonate with your situation?"

The querent responds. "Well, I've been having a hard conversation with my partner..."

The reader builds on this. "And here in the near future position is the Two of Cups—which represents partnership, emotional connection, mutual commitment. So perhaps this difficult conversation is leading toward deeper connection..."

This is collaborative meaning-making. The reader provides interpretation. The querent confirms, denies, or reframes. The reading evolves as a dialogue.

The cards aren't providing information. They're providing prompts—starting points for a conversation that the querent actually needs to have. The reading becomes a semi-structured therapeutic dialogue, with the cards serving as a neutral third party that makes certain topics easier to address.

Many tarot readers understand this explicitly. They're not claiming psychic powers. They're using the cards as a tool for helping people access and articulate their own concerns.

Why 78 Works

There's something important about the size of the deck.

With only a few cards—say, 10—you'd see the same images constantly. The system would feel repetitive, its meanings obvious.

With too many cards—say, 500—the system would be unwieldy. You couldn't learn the meanings. Each reading would feel disconnected from the last.

78 hits a sweet spot. Large enough for variety, small enough for familiarity. Large enough that specific cards feel significant when they appear, small enough that you develop relationships with individual cards.

The combination of Major and Minor Arcana creates two levels: the big themes and the specific situations. This matches how life actually works—we have overarching patterns and daily variations.

The system evolved to fit human cognitive constraints. That's why it works. That's why variants with radically different structures (like Lenormand, with 36 cards) feel different—they're optimized for different cognitive experiences.

The Modern Proliferation

Today there are thousands of tarot decks. The traditional Rider-Waite imagery has been reinterpreted through every possible lens: feminist tarot, Black tarot, queer tarot, Star Wars tarot, cat tarot.

This proliferation reveals something about how the system works. The specific images are replaceable. The structure is what matters.

78 positions in a semantic space. 22 major themes, 56 specific situations. Positions in spreads with designated meanings. The underlying architecture stays constant; the imagery varies.

A good modern deck isn't just an aesthetic choice. It's a resonance choice. If you connect more with images from your own cultural background, those images will serve as better projective surfaces. The divination will feel more meaningful because the initial raw material is closer to your own symbolic vocabulary.

The Barnum Dynamic

Return to the Barnum effect. The Three of Swords means "heartbreak, betrayal, painful truths." That's vague enough to apply to almost anyone.

But here's the thing: vague doesn't mean useless.

If you draw the Three of Swords and think "that doesn't apply at all"—well, now you've clarified something. You've established that heartbreak isn't your current concern.

If you draw it and think "oh god, yes"—you've identified something you need to address.

If you draw it and think "maybe... there's something difficult I've been avoiding"—you've opened a door.

The Barnum effect isn't just about being fooled. It's about being prompted. Vague statements invite you to do the specifying. The cards say "think about loss." You think about your specific losses. The cards have done their job.

Tarot as Technology

Strip away the occultism and tarot is a structured randomization system with projective imagery.

The randomization breaks habitual thought patterns. You can't choose which card to draw. Whatever comes up, you have to work with it.

The imagery provides starting material. You're not working with pure abstraction—you're working with pictures that suggest themes, stories, emotional tones.

The structure (spreads, positions, suits) provides framework. You're not just free-associating—you're interpreting within a narrative structure.

Put together, this is a remarkably sophisticated tool for psychological exploration. Not because it's magic. Because it's well-designed.

78 cards became a mirror because humans are excellent at seeing themselves in mirrors—especially mirrors that show us slightly abstracted, slightly defamiliarized versions of our concerns. Tarot works because projection works, narrative works, structured randomness works.

And it's lasted 600 years because it's genuinely useful for the purposes people use it for.

Further Reading

- Decker, R. & Dummett, M. (2002). A History of the Occult Tarot. Duckworth. - Pollack, R. (1980). Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom. Weiser Books. - Place, R. M. (2005). The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination. Tarcher.

This is Part 3 of the Divination Systems series. Next: "Astrology: The Persistence of an Unfalsifiable System."

Comments ()