The Bayesian Brain: Prediction All the Way Down

The Bayesian Brain: Prediction All the Way Down

Series: The Free Energy Principle | Part: 6 of 11

Your brain is not a camera recording reality. It's a prediction engine generating reality.

Right now, most of what you're seeing isn't coming from your eyes—it's coming from your visual cortex's best guess about what's out there. The actual sensory data contributes maybe 10% of the neural activity in visual areas. The other 90% is prediction, cascading down from higher regions.

You think you see the world. What you actually see is your brain's model of the world, continuously tested against sparse sensory evidence and updated only when prediction fails.

This is the Bayesian brain hypothesis—the idea that neural processing is fundamentally about probabilistic inference, with the brain constantly predicting incoming data and updating beliefs when predictions err. It's the neuroscientific flesh on the FEP skeleton.

And the evidence for it is everywhere.

Perception as Controlled Hallucination

Anil Seth calls perception "controlled hallucination"—the brain hallucinates reality, constrained by sensory input.

Without sensory input (like in sensory deprivation or certain psychedelic states), the hallucination runs unchecked. You perceive things that aren't there because there's no bottom-up data to contradict top-down predictions.

With normal sensory input, the hallucination is tightly controlled. Your predictions match incoming data closely, so the percept feels veridical. But it's still constructed—a hypothesis about hidden causes, rendered convincing by minimal prediction error.

Evidence:

Binocular rivalry: Present different images to each eye. Your brain doesn't blend them or see both—it alternates, because only one interpretation can minimize free energy at a time.

Perceptual filling-in: Your retina has a blind spot where the optic nerve exits. You don't see a hole. Your brain predicts what "should" be there based on surrounding context and fills it in seamlessly.

Change blindness: Huge changes in visual scenes go unnoticed if they don't violate expectations. You're not actually seeing everything—you're checking that the visual field matches predictions.

The dress: The famous photo that looked gold-white to some, blue-black to others. Not ambiguous input—ambiguous priors. Different assumptions about lighting conditions led to different inferred colors. Both were "correct" given their models.

All of these make sense if perception is inference under a generative model. They're puzzling if perception is passive reception.

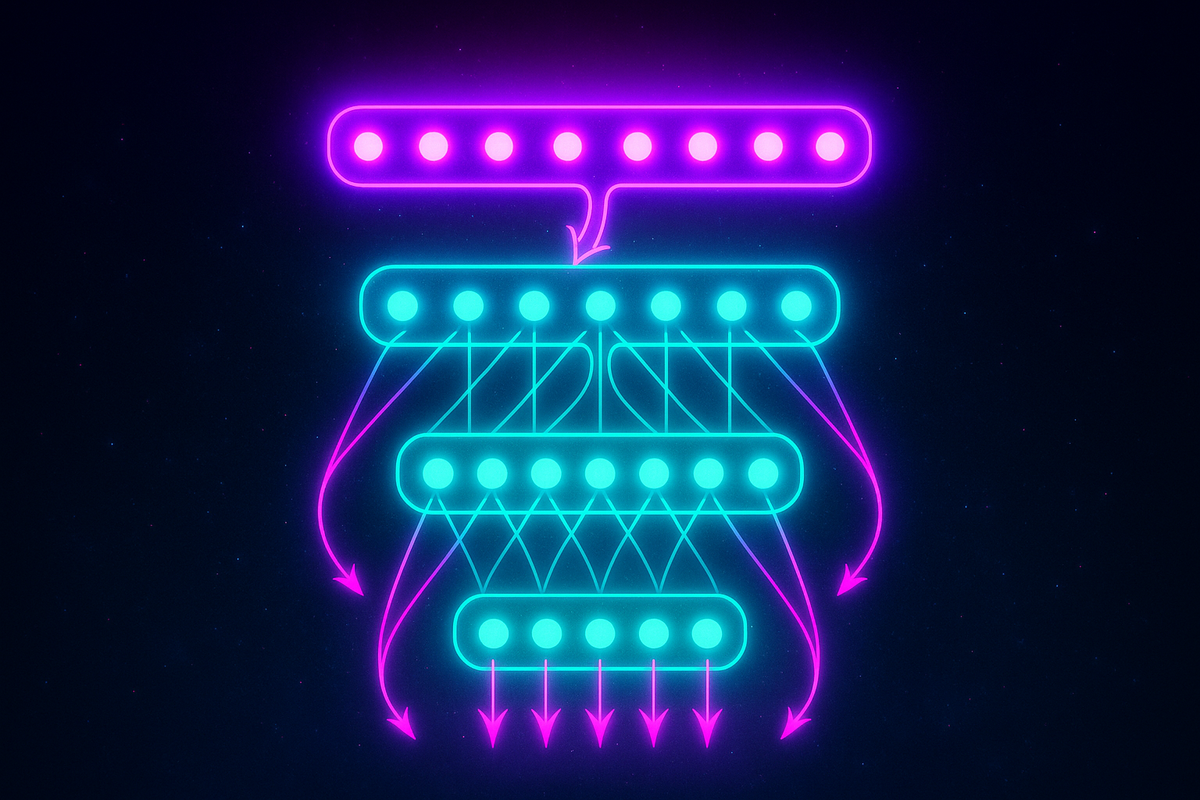

Hierarchical Predictive Coding

The brain's architecture reflects its function: hierarchical predictive coding.

Lower levels (sensory cortex): Represent specific features—edges, orientations, colors, pitches.

Higher levels (associative cortex): Represent abstract causes—objects, categories, scenes, meanings.

Information flows bidirectionally:

Top-down (predictions): Higher levels predict what lower levels should be signaling.

Bottom-up (errors): Lower levels send only the mismatch between prediction and actual input.

This is computationally efficient. Instead of sending all sensory data up the hierarchy, send only the unexpected. If predictions are good, transmission is minimal. Bandwidth is conserved.

Neuroanatomically:

- Deep layers of cortex: Send predictions down

- Superficial layers: Send errors up

- Connections between layers: Implement prediction and error computation

Different cell types encode predictions vs. errors. Pyramidal cells in deep layers predict. Superficial pyramidal cells signal errors. The whole cortical architecture implements variational inference.

Precision Weighting and Attention

Not all prediction errors matter equally. In fog, visual errors are unreliable—ignore them. In darkness with clear sound, auditory errors are trustworthy—weight them heavily.

The brain implements this through precision weighting—modulating the gain (amplification) of prediction errors before they drive belief updates.

High precision: Errors are amplified, strongly influence beliefs. You trust the sensory data.

Low precision: Errors are suppressed, weakly influence beliefs. You trust prior predictions.

Neurally, precision is thought to be encoded by neuromodulators (dopamine, acetylcholine, norepinephrine) that change the gain on error-signaling neurons.

This is what attention is. Attending to something is increasing the precision of prediction errors from that source. You're saying "weight these errors more when updating beliefs."

Why does attention improve perception? Because high-precision errors drive faster, more accurate inference. You converge on the true cause more quickly.

Why can't you attend to everything? Because precision is metabolically expensive (high firing rates) and computationally brittle (unstable if too many signals have maximum gain). You have to budget precision—allocate it to the most task-relevant channels.

Prediction Errors as Surprise

Remember from Part 2: surprise (in FEP terms) is the negative log probability of sensory data under the model.

In predictive coding, prediction error is surprise. When your model predicts X and you sense Y, the error magnitude reflects how surprising Y is given X.

Minimizing prediction error = minimizing surprise = minimizing free energy. It's all the same process, described at different levels:

- Mathematical: Minimizing free energy (variational inference)

- Computational: Minimizing prediction error (predictive coding)

- Neural: Adjusting synaptic weights and activity to reduce error signals

The Bayesian brain hypothesis says the latter two implement the first.

Learning as Synaptic Tuning

Short-term inference updates neural activity (firing rates). Long-term learning updates neural connectivity (synaptic weights).

Perception (fast): Adjust activity to minimize current errors. This is belief updating.

Learning (slow): Adjust weights to minimize expected errors over time. This is model updating.

Both are gradient descent on free energy, just at different timescales.

Hebbian learning ("neurons that fire together wire together") is gradient descent on prediction error. Synapses strengthen when presynaptic predictions correlate with postsynaptic errors, weakening when they don't. Over time, this tunes the generative model to predict sensory data better.

This explains why learning takes time. You can't instantly acquire a new skill because synaptic weights change slowly (hours to days). But you can quickly update beliefs about novel situations because neural activity changes fast (milliseconds to seconds).

Why Illusions Are Features, Not Bugs

Optical illusions aren't failures of perception—they're successes of inference under the wrong model.

The hollow mask illusion: A concave (inward) mask looks convex (outward) because your brain has a strong prior: "faces are convex." The prediction is so strong it overrides the actual sensory data. You minimize free energy by perceiving a convex face, even though the true cause is concave.

The Müller-Lyer illusion: Lines of equal length look different because the arrow endings create depth cues. Your brain infers different distances and scales perceived length accordingly. It's correct inference given the model—it's just that the model includes assumptions about 3D structure that don't apply to the 2D stimulus.

Placebos: Expect pain relief, and your brain predicts reduced pain signals. Endogenous opioids activate to make the prediction true. The relief is real—it's not "just in your head." It's the brain making its predictions come true.

Illusions show that perception is inference. The brain is trying to minimize free energy, not represent reality perfectly. Usually these align. When they don't, you get illusions.

Predictive Processing and Mental Illness

If the brain is a prediction machine, psychopathology might be prediction dysfunction.

Autism: Over-weighting sensory evidence relative to priors. The world feels unpredictable because you don't use learned regularities to filter noise. Preference for routine = attempt to reduce environmental variance.

Schizophrenia/psychosis: Under-weighting sensory evidence relative to priors. Top-down predictions overwhelm bottom-up data. Hallucinations are unchecked predictions. Delusions are high-confidence priors resistant to disconfirmation.

Anxiety: Over-predicting threat. High precision on threat-related prediction errors. The world feels dangerous because your model constantly generates threat predictions and weight them heavily.

Depression: Learned helplessness encoded as high expected free energy for all actions. No policy minimizes G, so behavioral activation drops. Anhedonia is failed reward prediction—nothing generates positive prediction errors anymore.

PTSD: Trauma fragments the model. Certain contexts trigger high-magnitude prediction errors because the model broke at the moment of trauma. Flashbacks are the brain re-experiencing the original prediction failure, trying to integrate it.

If this is right, treatment should target inference:

- Exposure therapy: Update priors by repeatedly experiencing disconfirming evidence.

- Cognitive therapy: Explicitly revise generative models (beliefs about self/world).

- Mindfulness: Reduce precision on thought-level predictions, increase precision on sensory input.

- Psychedelics: Temporarily relax high-level priors, allowing model revision.

The Bayesian Brain Is Still Just a Brain

The Bayesian brain hypothesis doesn't claim neural tissue does symbolic probability calculations. It claims brain dynamics approximate Bayesian inference through neuronal interactions.

Neurons don't "know" Bayes' theorem. But populations of neurons, connected in hierarchies with the right dynamics, functionally implement something equivalent.

This is important: the math (Bayesian inference, variational free energy) describes what the system is doing at a computational level. The biology (neurotransmitters, synapses, firing patterns) implements it at a physical level. They're different levels of description of the same process.

Prediction All the Way Down

If brains are prediction machines, several implications:

You never perceive the present. You always perceive your best prediction about what's causing recent input, updated slightly by errors.

Consciousness might be the model. The felt quality of experience could be what it's like to be a hierarchical generative model from the inside.

Free will is model-based action selection. You "choose" by computing expected free energy for policies and sampling from the distribution.

The self is a prediction. Your sense of being a continuous "you" is a high-level inference about the hidden cause integrating across sensory streams and time.

And beyond brains: any system that maintains structure through prediction might be implementing Bayesian inference in its own substrate. Cells, immune systems, ecosystems—wherever you find prediction error minimization, you find something functionally Bayesian.

The universe doesn't compute probabilities. But systems that persist in it must act as if they do.

Further Reading

- Rao, R. P., & Ballard, D. H. (1999). "Predictive coding in the visual cortex: a functional interpretation of some extra-classical receptive-field effects." Nature Neuroscience, 2(1), 79-87.

- Friston, K. (2010). "The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?" Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127-138.

- Clark, A. (2013). "Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science." Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 181-204.

- Seth, A. K. (2021). Being You: A New Science of Consciousness. Dutton.

- Hohwy, J. (2013). The Predictive Mind. Oxford University Press.

This is Part 6 of the Free Energy Principle series, exploring how predictive processing implements Bayesian inference in neural tissue.

Previous: Active Inference

Next: Beyond Biology: FEP as a Theory of Everything That Persists

Comments ()