The Generative Model: Building World Models for Active Inference Agents

The Generative Model: Building World Models for Active Inference Agents

Series: Active Inference Applied | Part: 2 of 10

The difference between an active inference agent that works and one that fails catastrophically usually comes down to a single question: how well does its generative model capture the structure of its world?

This isn't philosophical abstraction. It's the engineering bottleneck. You can have perfect message passing algorithms, optimized belief propagation, and elegant expected free energy minimization—but if your generative model doesn't reflect the actual causal structure of the environment, your agent will hallucinate its way into failure states with mathematical precision.

The generative model is the core of active inference. It's how an agent represents what it expects to happen—the probabilistic structure of how hidden states generate observations, how actions influence outcomes, how the world unfolds over time. Get this right, and you have an agent that can navigate uncertainty, plan under ambiguity, and adapt to novel situations. Get it wrong, and you have an expensive random walk with Bayesian pretensions.

This article unpacks the engineering challenge of building generative models for active inference agents. Not the theory—we covered that in the introduction. This is about implementation: what choices you face, what trade-offs matter, and what actually works when you try to instantiate world models in code.

What a Generative Model Actually Does

A generative model is a joint probability distribution over observations, hidden states, policies, and time. Formally:

P(o, s, π) = P(o|s)P(s|π)P(π)

Where:

- o = observations (what the agent senses)

- s = hidden states (what's actually happening in the world)

- π = policies (sequences of actions the agent might take)

Translated: the generative model specifies how the world generates observations from hidden states, how actions influence state transitions, and which policies are a priori plausible.

This is the agent's theory of its world. Not a literal replica, but a probabilistic compression of the regularities that matter for prediction and control. The agent doesn't know what's really happening—it only has access to observations. The generative model is its best guess about the latent structure producing those observations, updated continuously through Bayesian inference.

Why this matters: Active inference agents don't learn arbitrary input-output mappings like reinforcement learning agents. They learn to infer the hidden causes of their sensory data, then act to minimize surprise about future observations. The generative model is the scaffolding that makes this inference tractable. Without it, there's no active inference—just random sampling in sensory space.

The Discrete State Space Formulation

Most practical active inference implementations start with discrete state spaces—finite sets of categorical states rather than continuous variables. This isn't a limitation; it's a design choice that makes inference computationally feasible.

In the discrete formulation, the generative model consists of:

1. The A Matrix (Observation Model)

A[o, s] = P(o|s) — the likelihood of observation o given hidden state s.

This encodes your agent's sensor model. If state s = "apple in front of me," what distribution over observations (color, shape, smell) should I expect?

Example: A grid-world robot with noisy vision:

- True state: Cell (3,2)

- Observation: "Something in cells (3,2), (3,1), or (4,2)" with probabilities [0.7, 0.15, 0.15]

- The A matrix captures this uncertainty: each hidden state maps to a distribution over possible sensory readings.

Engineering choice: How precise is your observation model? High precision (sharp distributions) means the agent trusts its sensors. Low precision (flat distributions) means sensory data is treated as unreliable. This precision is a hyperparameter you tune based on your environment's actual sensor noise.

2. The B Matrix (Transition Model)

B[s_t+1, s_t, a] = P(s_t+1 | s_t, a) — the probability of transitioning to state s_t+1 from state s_t under action a.

This is your world's physics. How do states evolve? What do actions actually do?

Example: Same grid-world robot:

- Action: "Move North"

- Current state: Cell (3,2)

- Next state distribution: Cell (3,3) with p=0.9, Cell (3,2) with p=0.1 (action fails)

The B matrix encodes controllability: which actions reliably change which states, and which transitions are stochastic. In a deterministic environment, each B[:, s, a] is a one-hot vector. In a stochastic world, it's a proper probability distribution.

Critical insight: The B matrix defines what the agent can control. States unreachable under any policy are uncontrollable. This matters for planning—expected free energy calculations only consider state transitions that actions can actually influence.

3. The C Matrix (Preferences)

C[o] = log P(o) — the agent's prior preference over observations.

This is not a reward function. It's a probability distribution representing which observations the agent expects (or prefers) to encounter. High C values mean "I expect to see this observation in my preferred futures." Low C values mean "This is surprising and undesirable."

Example: A foraging agent:

- C["food"] = high → expects to observe food

- C["empty"] = low → does not expect emptiness

- C["predator"] = very low → strongly expects to avoid predators

The agent doesn't maximize C directly. Instead, it minimizes expected free energy, which includes terms for both pragmatic value (achieving preferred observations) and epistemic value (resolving uncertainty). The C matrix shapes the pragmatic term.

Subtle distinction: In reinforcement learning, rewards are external signals the environment provides. In active inference, preferences are internal to the generative model—the agent's own expectations about what it should observe. This makes active inference agents self-motivated: they act to fulfill their own predictions, not to chase external carrots.

4. The D Matrix (Initial State Prior)

D[s] = P(s_0) — the probability distribution over initial states.

Where does the agent expect to start? This matters more than you'd think. If D is concentrated on a small region of state space, the agent has strong beliefs about its starting configuration. If D is uniform, the agent begins maximally uncertain.

Practical use: D influences early behavior. An agent with a sharp D will act confidently from the first timestep, committed to a particular interpretation of its initial observations. An agent with a flat D will engage in epistemic foraging—exploration to figure out where it actually is before committing to goal-directed action.

Constructing the Generative Model: Where Do These Matrices Come From?

Here's the engineering reality: you have to specify these matrices. The agent doesn't learn them automatically (in basic active inference). You, the designer, provide the probabilistic structure.

This is both a constraint and a feature. It means you need domain knowledge. But it also means the agent can operate from the first timestep with structured priors, rather than requiring thousands of episodes to stumble onto basic regularities like "walls block movement" or "food is at specific locations."

Strategy 1: Hand-Craft from Domain Knowledge

For simple, well-understood environments, you can directly encode the generative model. Grid worlds, board games, and simulated tasks with known physics work well. Write down the transitions (B), define observation noise (A), set preferences (C), and the agent immediately understands its world. Limitation: doesn't scale to complex, partially-known environments like "navigate a real city."

Strategy 2: Learn from Data

For complex domains, pre-train the generative model on observational data. Collect state-observation-action tuples, use maximum likelihood to learn A and B, hand-specify C and D, then deploy. Works for robotics with complex sensors, environments with unknown but consistent dynamics, or domains where you have simulation data.

Hybrid approach: Start with a hand-crafted skeleton (rough dynamics), then refine with data. This provides structure while allowing adaptation to actual sensor noise and stochasticity.

Strategy 3: Hierarchical and Compositional Models

Real-world generative models aren't monolithic matrices. They're compositional: built from reusable components that represent different aspects of the world.

Deep temporal models: States have hierarchical structure. High-level states ("in kitchen") persist over many timesteps. Low-level states ("gripper position") change rapidly. The B matrix reflects this temporal abstraction—slow variables provide context for fast variables.

Factored state spaces: Instead of enumerating every possible world configuration, factor the state into independent (or weakly coupled) components.

Example:

- Object position (10 discrete locations)

- Object color (5 possible colors)

- Agent position (10 locations)

Rather than 10 × 5 × 10 = 500 explicit states, represent as three factors with learned dependencies. The generative model becomes a Dynamic Bayesian Network where nodes correspond to factors and edges encode conditional dependencies.

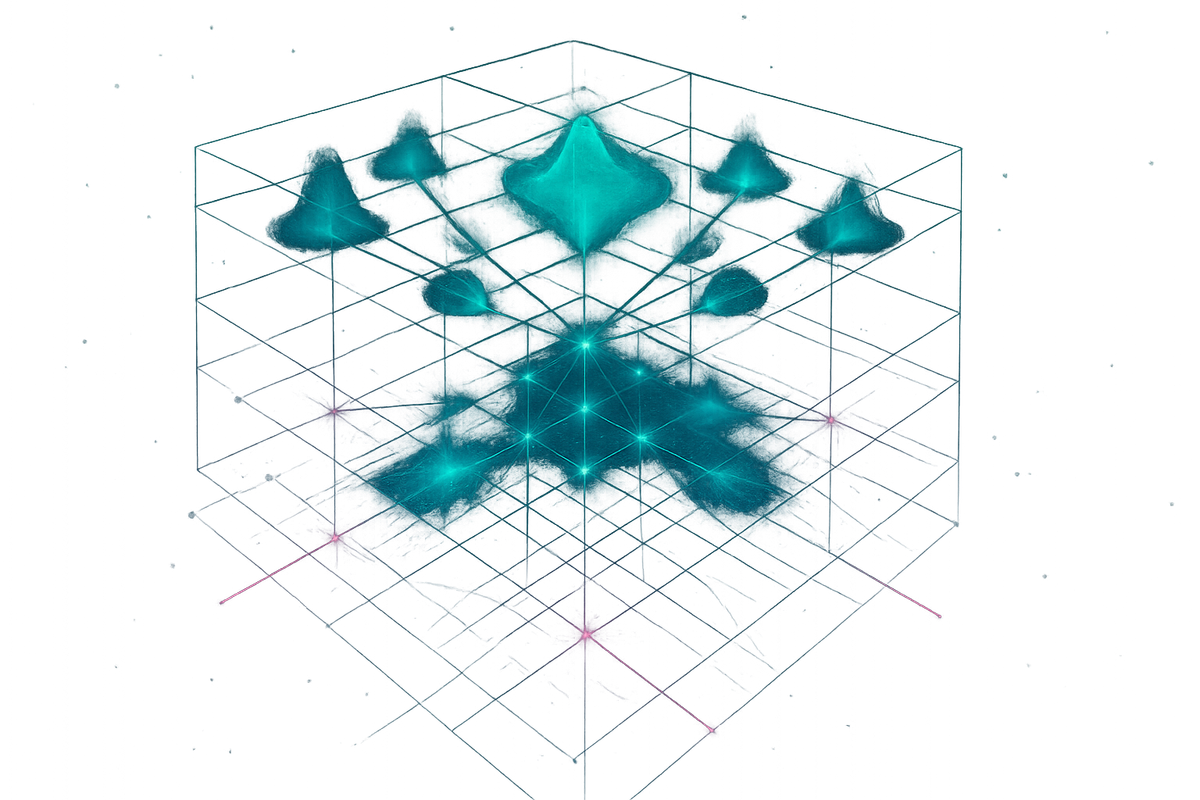

This is where active inference meets probabilistic programming. Tools like RxInfer (which we'll cover in Article 5) let you specify generative models as factor graphs rather than giant matrices. You define the causal structure—which variables influence which—and the inference engine automatically derives message passing schedules.

Why this matters: Factorization makes scaling possible. A flat state space with n dimensions and k values per dimension requires k^n states—exponential blowup. Factored representations grow linearly with the number of factors, as long as dependencies are sparse.

Precision and Uncertainty: The Role of Hyperparameters

The A, B, C, and D matrices define the structure of the generative model. But there's another layer: precision parameters that control how much the agent trusts each component.

Observation precision: Controls sensory confidence. High precision means the agent trusts its sensors and updates beliefs quickly. Low precision means it discounts noisy observations and relies on predictions. Match this to actual sensor noise—too high causes brittle overfitting, too low causes sluggish updates.

Transition precision: Controls belief in action reliability. High precision means "actions produce expected effects." Low precision means "the world is unpredictable," triggering more exploration.

Preference precision: Controls exploitation vs exploration. High precision (like low temperature in softmax) means greedy pursuit of goals. Low precision means flexible exploration. This implements the exploration-exploitation trade-off naturally—start with low precision to explore, anneal toward high precision for exploitation.

From Matrices to Message Passing: Implementing Inference

Once you've constructed A, B, C, D (and their precisions), the agent needs to infer hidden states and select actions. This happens through variational message passing—iterative updates that approximate the posterior distribution over states and policies.

We'll cover the algorithmic details in Article 4 (Message Passing and Belief Propagation), but the key point here: the generative model structure directly determines the inference procedure.

If your generative model is a Markov Decision Process (single-level, discrete time), inference reduces to forward-backward message passing (same as in Hidden Markov Models).

If your generative model is hierarchical (nested timescales), inference requires hierarchical message passing where higher levels provide context (priors) for lower levels.

If your generative model is a factor graph (compositional), inference becomes belief propagation on that graph—messages flow along edges, updating beliefs about each variable based on its Markov blanket.

Design implication: The computational cost of inference scales with the structure of your generative model. Dense, fully-connected models are expensive. Sparse, modular models are cheap. This is why factorization and hierarchy matter—they're not just representational elegance; they're computational necessity.

The Generative Model as Scientific Theory

Here's where active inference diverges philosophically from other AI frameworks: the generative model is a scientific theory about the world, and the agent is a scientist testing that theory.

When observations violate predictions (high surprise), the agent can: (1) update beliefs about hidden states (perception), (2) update the generative model itself (learning), or (3) change the world through action to match predictions (active inference).

Most implementations fix the generative model and focus on (1) and (3). But in principle, active inference allows model revision—if repeated surprise persists despite belief updates, the agent can infer that its A or B matrices don't match reality. This is structure learning under deployment: adapting beliefs about how the world works, not just where it is.

Current research frontier: Systems like RxInfer are exploring online structure learning—agents that revise their own generative models when evidence violates structural assumptions. When this works, you get agents that build causal models, not stimulus-response associations.

Practical Trade-Offs: Expressiveness vs Tractability

Every design choice in generative model construction is a trade-off:

Discrete vs Continuous States

Discrete: Exact inference possible (finite state spaces). Easy to interpret. Scales poorly (curse of dimensionality).

Continuous: Scales to high-dimensional spaces (images, sensor streams). Requires approximations (Laplace, sampling, neural networks). Harder to interpret.

Current practice: Discrete for cognitive models, gridworlds, simple robotics. Continuous for vision-based tasks, complex control.

Flat vs Hierarchical

Flat: Simple, easy to implement. No temporal abstraction. Struggles with long horizons.

Hierarchical: Natural temporal abstraction. Compositional reuse. More complex inference.

Current practice: Flat for proof-of-concept. Hierarchical for realistic tasks (robotics, language).

Hand-Crafted vs Learned

Hand-crafted: Works from the first timestep. Requires domain expertise. Doesn't adapt to distribution shift.

Learned: Adapts to complex environments. Requires training data. May learn spurious correlations.

Current practice: Hybrid. Hand-craft structure, learn parameters. Use domain knowledge for causal skeleton, data for precise probabilities.

Fixed vs Adaptive

Fixed: Computationally cheap. Predictable behavior. Brittle to novelty.

Adaptive: Handles non-stationarity. Expensive (meta-learning overhead). Risk of catastrophic forgetting.

Current practice: Fixed for controlled environments. Adaptive for open-world deployment (still experimental).

Case Study: Implementing a Grid-World Generative Model

Let's make this concrete. You want an active inference agent to navigate a 5×5 grid, find a reward, and avoid a trap.

State space: 25 positions (x,y) with observable goal and trap markers

A matrix (5×25): Maps positions to observations {North, South, East, West, Here} indicating direction to landmarks. Introduce 80% accuracy, 10% adjacent confusion, 10% noise.

B matrix (25×25×5): Defines transitions for actions {MoveNorth, MoveSouth, MoveEast, MoveWest, Stay}. Deterministic movement with wall collisions, plus 10% action failure rate.

C matrix (5-vector): Preferences over observations. C["GoalHere"] = +10, C["TrapHere"] = -10, C[other] = 0.

D matrix (25-vector): Initial belief concentrated at starting position (0,0).

With these matrices, the agent infers its position from noisy observations, predicts action consequences, evaluates policies by expected free energy, and acts to minimize surprise while achieving preferred observations. No reward signal needed—it acts to fulfill its own predictions.

The Generative Model as the Agent's Umwelt

In biology, Umwelt (Jakob von Uexküll's concept) refers to an organism's subjective perceptual world—the slice of reality accessible through its sensors and cognitive structure.

The generative model is the active inference agent's Umwelt. It defines what the agent can perceive (A), control (B), care about (C), and expect (D). This isn't a bug—it's the fundamental insight: agents don't model objective reality; they model the reality that matters for their survival and goals.

A bat's generative model includes echolocation; a human's doesn't. A chess engine models board positions, not wood grain. Each agent carves reality at the joints relevant to its niche.

Engineering lesson: Don't build a generative model of "everything." Build one of what your agent needs to predict and control. Irrelevant details expand the state space without improving performance. The best generative model isn't the most detailed—it's the one that compresses the world's structure into the smallest set of states and transitions that still supports successful inference and action.

What's Next: Expected Free Energy and Action Selection

We've constructed the generative model—the agent's theory of its world. But how does it use this model to choose actions?

That's the subject of the next article: Expected Free Energy, the objective function that turns world models into plans. We'll unpack how agents evaluate policies, balance exploration and exploitation, and implement planning as inference.

The generative model gives the agent a map. Expected free energy is how it navigates.

Further Reading

- Friston, K., FitzGerald, T., Rigoli, F., Schwartenbeck, P., & Pezzulo, G. (2017). "Active Inference: A Process Theory." Neural Computation, 29(1), 1-49.

- Da Costa, L., Parr, T., Sajid, N., Veselic, S., Neacsu, V., & Friston, K. (2020). "Active Inference on Discrete State-Spaces: A Synthesis." Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 99, 102447.

- Heins, C., Millidge, B., Demekas, D., Klein, B., Friston, K., Couzin, I., & Tschantz, A. (2022). "pymdp: A Python Library for Active Inference in Discrete State Spaces." Journal of Open Source Software, 7(73), 4098.

- Uexküll, J. von (1957). "A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men: A Picture Book of Invisible Worlds." Instinctive Behavior: The Development of a Modern Concept.

This is Part 2 of the Active Inference Applied series, exploring the engineering challenges of building active inference systems.

Previous: From Theory to Code: The Active Inference Implementation Revolution

Next: Expected Free Energy: The Objective Function That Plans

Comments ()