The Math Behind "Something Feels Off"

Kullback-Leibler divergence explains subjective discord: the measurable gap between predictive models and reality across psychology, relationships, and culture.

The Math Behind "Something Feels Off"

Formative Note

This essay represents early thinking by Ryan Collison that contributed to the development of A Theory of Meaning (AToM). The canonical statement of AToM is defined here.

You walk into a room and something feels wrong.

Nothing obvious. The furniture is where it should be. The lighting is normal. No one is screaming. But somewhere beneath conscious processing, your system has registered a mismatch. Your model predicted one thing. Reality delivered another. The gap between them is small enough that you can't name it, but large enough that your body knows.

This is the feeling of divergence.

Your brain maintains a model of reality—a generative model that predicts what you should encounter, moment by moment, across every sensory channel. When predictions match inputs, the world feels coherent. When predictions fail, error signals propagate. The larger the failure, the stronger the signal.

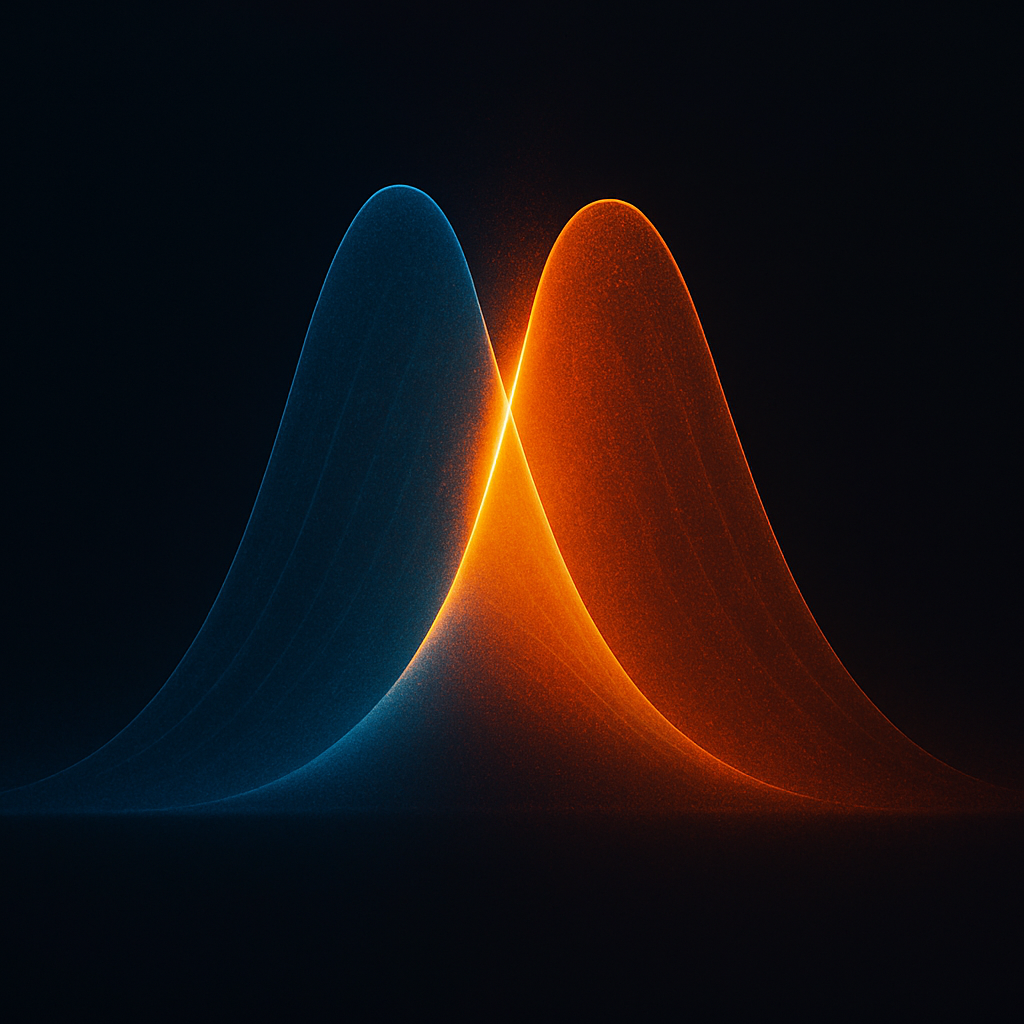

The mathematical measure of this mismatch is called Kullback-Leibler divergence—KL divergence for short. It quantifies, precisely, how far your model has drifted from reality. And understanding it illuminates everything from subtle unease to existential crisis, from therapeutic breakthrough to cultural collapse.

What KL Divergence Measures

KL divergence compares two probability distributions: the one you have (your model) and the one that's actually generating your experience (reality, or at least, the reality your senses can access).

The formula looks like this: D_KL(P || Q) = Σ P(x) log[P(x) / Q(x)]

Don't worry about parsing it mathematically. The intuition is what matters.

KL divergence asks: if reality is actually distributed according to P, how surprised will you be if you're predicting according to Q? It measures the extra uncertainty you carry—the additional prediction error you accumulate—because your model doesn't match the world.

Zero KL divergence means perfect alignment. Your model predicts exactly what happens. No surprise, no error, no update needed.

Positive KL divergence means mismatch. Your model expects things that don't happen, or fails to expect things that do. The larger the divergence, the greater the gap.

And here's the key insight: KL divergence isn't symmetric. D_KL(P || Q) is not the same as D_KL(Q || P). The divergence from your model to reality is different from the divergence from reality to your model.

This asymmetry captures something real. It matters whether you're failing to predict what happens (underestimating reality's complexity) or predicting things that don't happen (overestimating patterns that aren't there). Both are errors. They're different errors.

The Gradient of Mismatch

KL divergence gives us a number. But what matters for experience is the gradient—how sharply divergence changes as you move around the manifold.

A steep KL gradient means your model must deform rapidly to align with incoming information. You're getting data that violently contradicts your predictions. The world is shouting that you're wrong.

A shallow KL gradient means your model is reasonably close. Updates can be gentle. The world is whispering adjustments, not screaming corrections.

The "something feels off" experience is the felt sense of KL gradient—the pressure of divergence without yet knowing the content. Your predictive system has registered: there's a gap here. It hasn't yet told you what the gap is. But it's told you there is one.

This is why intuition works. Intuition isn't mystical. It's subthreshold divergence detection. Your model is mismatching reality in ways too subtle to articulate, but the KL gradient is non-zero. Something feels off because something is off—your predictions don't quite fit, and the error signal has begun.

Chronic Divergence

What happens when KL divergence stays high for a long time?

The system has three options. Update the model. Change the inputs. Or accumulate stress.

Updating the model means revising beliefs to match reality. This is learning. If your model of a relationship predicted support and you're receiving criticism instead, you can update: "this relationship is different than I thought." The divergence drops because your model now matches what's happening.

Changing the inputs means acting on the world to make it conform to your predictions. This is active inference. If reality doesn't match your model, sometimes you can change reality. You can leave the unsupportive relationship, find a different job, move to a different environment. The divergence drops because the world now matches your model.

When neither option works—when you can't update your model fast enough and you can't change your inputs—the divergence persists. And persistent divergence is expensive.

Every moment of high divergence means prediction error flooding the system. Error signals demand processing. They demand attention, metabolic resources, corrective action. A system under chronic prediction error is a system under chronic stress.

This is the computational description of burnout. Not "working too hard" in some abstract sense. But maintaining models that don't match reality and being unable to either update them or escape the mismatch. The divergence accumulates. The gradients stay steep. The system exhausts itself trying to reconcile what it expects with what it receives.

Trauma as Divergence Catastrophe

Trauma is what happens when KL divergence spikes beyond the system's capacity to integrate.

Under normal circumstances, divergence produces update. Something unexpected happens, prediction error signals the mismatch, the model revises, divergence drops. The system learns.

Trauma occurs when the divergence is too large, too fast, too overwhelming to process. The prediction error isn't a signal—it's a flood. The model can't update because updating requires comparison between prediction and outcome, and the outcome is too far from anything the model can represent.

Think about what this means concretely. A child's model of their caregiver predicts safety. Then the caregiver becomes the source of harm. The KL divergence between "safe haven" and "source of attack" isn't just large—it's incoherent. The model can't smoothly update from one to the other because there's no path. The gradient is infinite. The manifold has a discontinuity.

The system can't integrate this. So it does something else. It fragments. It creates multiple models that don't communicate—a model where the caregiver is safe, a model where the caregiver is dangerous, and a dissociative boundary between them. The divergence isn't resolved; it's partitioned. The cost is internal coherence, but the benefit is avoiding a divergence that would destroy the system entirely.

PTSD symptoms are divergence phenomena. Flashbacks are moments when sensory input suddenly matches the traumatic model rather than the current model—the KL divergence with "safe present" spikes while the divergence with "dangerous past" drops. Hypervigilance is the system maintaining high sensitivity to divergence in threat-relevant domains because the cost of missing a danger signal was once catastrophic. Avoidance is routing around regions of the manifold where divergence gradients are too steep to navigate.

Trauma isn't a failure to process an event. It's a geometric impossibility—a divergence too severe to integrate, leaving the manifold permanently scarred.

The Double Bind as Divergence Trap

Some situations create divergence that cannot be reduced.

Gregory Bateson described the double bind: a communication pattern where every possible response increases divergence. You can't satisfy the demand. You can't refuse it. You can't comment on the trap you're in. Every move makes things worse.

In divergence terms: the double bind creates a region of the manifold with no low-divergence exits. Every direction is uphill. Every update increases mismatch. The system is stuck.

Chronic exposure to double binds produces a characteristic deformation of the manifold. The system learns that divergence cannot be reduced—that modeling reality accurately is impossible, that no action will align prediction with outcome. This is learned helplessness, but geometrically specified. The manifold has no smooth paths. The system stops trying to navigate because navigation always fails.

Escaping double binds requires something other than model updates within the trapped region. It requires changing scale—recognizing the trap as a trap, modeling the situation from outside it, creating new dimensions in which movement is possible. Often this requires another person who can see what you can't, whose external perspective reveals paths that look inaccessible from inside.

Relationships as Coupled Divergence

In relationship, you don't just model reality. You model another person who is also modeling you.

This creates coupled divergence dynamics. My model of you produces predictions. Your behavior either confirms them (low divergence) or contradicts them (high divergence). But your behavior is itself influenced by your model of me. We're not just predicting each other—we're predicting each other's predictions.

When this goes well, the result is attunement. Our models of each other are accurate. Divergence is low. We know what to expect from each other, and we deliver it. The relationship is coherent.

When this goes poorly, divergence accumulates. My model of you becomes outdated. Your model of me becomes warped. We're each predicting someone who doesn't match the person we're actually encountering. The gap grows. Interactions become confusing, frustrating, painful—not because anyone is bad but because the divergence has made us illegible to each other.

Relationship repair is divergence reduction. We update our models of each other. We communicate—literally transferring information that reduces prediction error. "When you said X, I interpreted Y. Is that what you meant?" This is explicitly closing the divergence gap, making the models converge, reducing the mismatch that makes relationship painful.

But some divergence can't be talked through. Some gaps are too large, some models too calcified, some histories too deforming. In those cases, the relationship either accepts chronic divergence—a low-grade wrongness that never resolves—or it ends, eliminating the divergence by eliminating the coupling.

Organizational Mismatch

Organizations have models of their environments. Markets, customers, competitors, regulations, technology. The organization's strategy is essentially a prediction: "Given what we believe about the world, here's how we should act."

KL divergence between organizational model and actual environment determines performance. Low divergence means the strategy fits. The organization predicts what happens and acts accordingly. High divergence means the strategy is misaligned. The organization is optimizing for a world that doesn't exist.

Strategic surprise is divergence spike. A competitor does something unexpected. A technology shifts. A market changes. The organization's model suddenly mismatches badly. Divergence was low; now it's high.

Some organizations update quickly. They revise their models, adjust their strategies, close the divergence gap. They learn. Other organizations can't update. The model is too entrenched—too politically defended, too structurally embedded, too foundational to identity. They persist with a misaligned model, accumulating divergence, wondering why everything is so hard.

Organizational death is often divergence death. The gap between model and reality became too large. The organization couldn't close it. Eventually, the accumulated mismatch made continued function impossible.

Cultural Drift

Cultures have collective models—shared predictions about how society works, what's valuable, what's true. These models are maintained through institutions, narratives, rituals, laws.

When cultural models match cultural reality, the society is coherent. People know what to expect. Norms are enforced consistently. Predictions about social behavior succeed.

When cultural models drift from cultural reality, divergence accumulates. The stated values don't match the practiced values. The official narrative doesn't match lived experience. The prediction of "how things work" fails more and more often.

This is the feeling of social decadence—not moral judgment but divergence detection. Something feels off because something is off. The collective model and the collective reality have separated. Nobody can quite name it, but everybody can feel it.

Cultural transformation happens when divergence becomes undeniable. A war, a plague, a technological revolution—something that makes the gap between model and reality impossible to ignore. The culture must update or collapse. Either the model changes or the society fragments.

The current cultural moment is saturated with divergence. Old models of economy, politics, identity, meaning are mismatching rapidly. New models haven't stabilized. We're all navigating high-divergence terrain, trying to predict a world that keeps violating predictions.

This is why everything feels unstable. Not because any particular thing is wrong, but because divergence is high everywhere and the paths to reducing it are unclear.

Living with the Gap

You can't eliminate KL divergence. A model that perfectly matched reality would be reality—and then it wouldn't be a model at all. The gap between map and territory is ineliminable. Some divergence is structural.

But you can relate to divergence differently.

You can notice it: that feeling of wrongness, of something off, is information. It's telling you there's a gap. Instead of pushing the feeling away or letting it consume you, you can be curious. Where is the gap? What prediction is failing? What does reality know that my model doesn't?

You can reduce it where possible: update your models when evidence comes in. Revise your beliefs when they're contradicted. Let the divergence teach you rather than punishing you.

You can accept it where necessary: some divergence can't be reduced right now. The evidence isn't in yet. The situation is genuinely ambiguous. Healthy cognition tolerates irreducible uncertainty without either collapsing into anxiety or forcing premature closure.

And you can recognize it in others: when someone seems irrational, consider that they might be navigating divergence you can't see. Their model and their reality are mismatching in ways that make their behavior make sense. The compassionate question isn't "why are they being crazy?" but "what divergence are they experiencing?"

The Math of Meaning

KL divergence is a technical concept. It's used in machine learning, in information theory, in statistical inference. It has formulas and theorems.

But it's also the math behind meaning.

Meaning is coherence. Coherence is low divergence—models that match, predictions that succeed, worlds that make sense. When divergence is low, meaning is high. When divergence spikes, meaning fragments.

The feeling that something is off is the first signal of meaning under threat. The prediction has failed. The model needs updating. The world has diverged from the story you were telling about it.

This isn't bad news. Divergence is the signal of learning trying to happen. Every mismatch is an invitation to revise, to understand better, to build a more accurate model.

The bad news is only when divergence becomes chronic—when you can't update, can't change inputs, can't find a way to close the gap. Then meaning erodes. The world becomes illegible. Coherence fails.

The math behind "something feels off" is the math behind meaning itself

Comments ()