The Shape of Surprise: What Information Geometry Actually Measures

The Fisher information metric measures how distinguishable beliefs are in predictive space. Explains why some therapeutic changes are geometrically difficult to traverse.

The Shape of Surprise: What Information Geometry Actually Measures

Formative Note

This essay represents early thinking by Ryan Collison that contributed to the development of A Theory of Meaning (AToM). The canonical statement of AToM is defined here.

How far apart are two beliefs?

Not in some vague metaphorical sense—precisely. Mathematically. If you believe there's a 70% chance of rain tomorrow and I believe there's a 40% chance, how much distance separates our models of reality? If a traumatized nervous system expects threat around every corner while a regulated one expects safety, how far apart are those two configurations?

These questions sound philosophical. They're not. They have answers. The answers come from a mathematical object called the Fisher information metric, and understanding it changes how you see minds, relationships, and meaning itself.

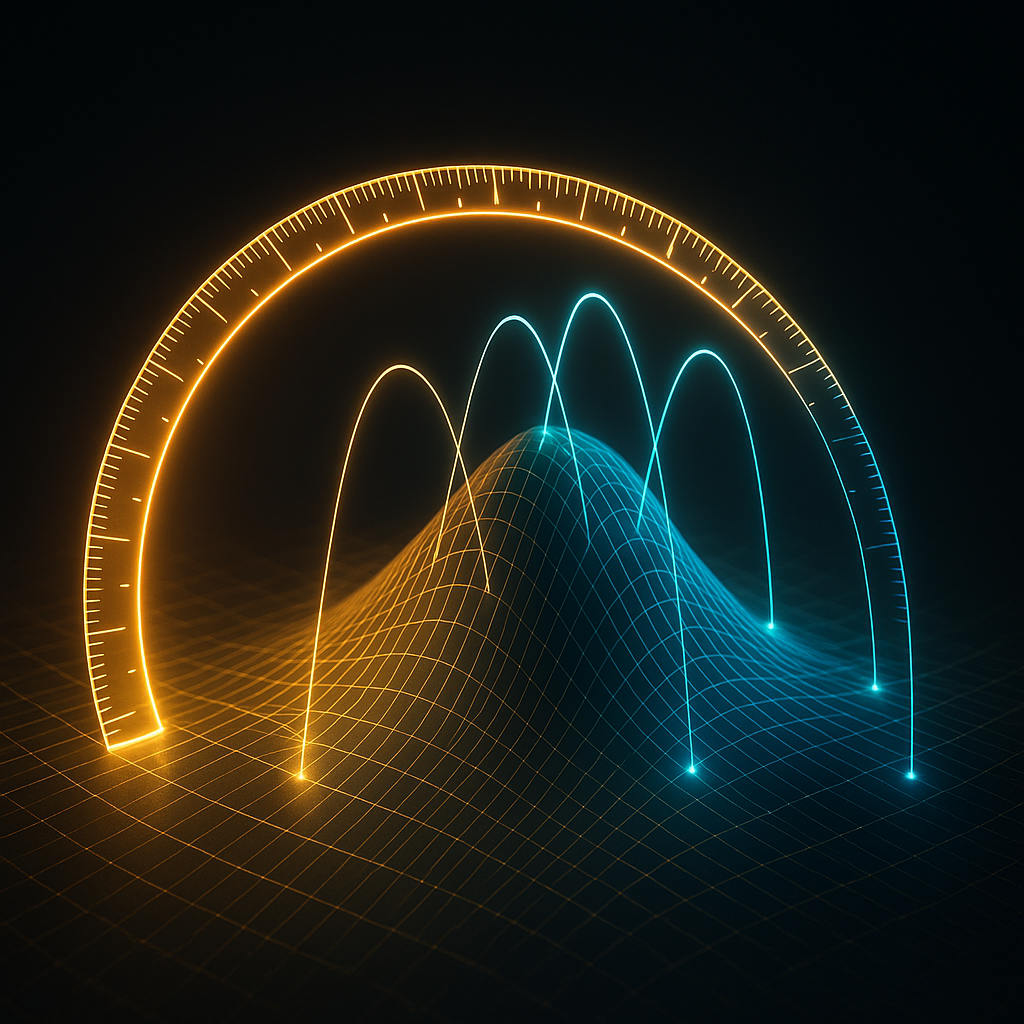

The Fisher metric is the ruler on the statistical manifold. It defines what "distance" means in the space of probability distributions. And the geometry it reveals isn't arbitrary—it emerges from the structure of information itself, from what it means for two models of reality to be distinguishable.

The Problem of Measuring Beliefs

Start with what doesn't work.

You might think you could measure the distance between probability distributions the way you measure the distance between points in ordinary space—just subtract the numbers and see how different they are. If I think there's a 70% chance of rain and you think 40%, the "distance" would be 30 percentage points.

But this is wrong, and seeing why it's wrong reveals something deep.

Consider two scenarios. In the first, I believe there's a 99% chance of rain and you believe 99.5%. In the second, I believe there's a 50% chance and you believe 50.5%. In both cases, we differ by half a percentage point. Same numerical distance.

But these aren't the same. Not even close.

In the second scenario, our difference is trivial. We both think it's basically a coin flip. Our predictions, our behaviors, our preparations for tomorrow will be nearly identical. The half-point gap changes nothing.

In the first scenario, we're both highly confident it will rain. But the structure of our confidence is different in a way that matters. My 99% leaves 1% probability for no rain. Your 99.5% leaves only 0.5%. You're twice as confident as I am in the extreme outcome. If we were betting, if we were making decisions based on these beliefs, if we were updating in response to evidence—the dynamics would be different.

The raw numerical difference doesn't capture how different the beliefs actually are. What matters is how distinguishable they are—how easily you could tell them apart by looking at their predictions, their behaviors, their responses to evidence.

This is what the Fisher metric measures. Not numerical distance. Informational distance. How far apart are two beliefs in terms of what they predict about the world?

The Fisher Information Metric

The Fisher information metric emerges from a simple question: if I'm at one point on the manifold and I take a tiny step, how much do my predictions change?

This sounds abstract. Make it concrete.

You have a model of some part of reality—say, how often a particular friend texts you. Your model assigns probabilities to different waiting times. Maybe you expect a text within an hour 60% of the time, within a day 90% of the time, within a week 99% of the time. This distribution is a point on the manifold.

Now imagine nudging one of the parameters of your model. You become slightly more optimistic—maybe now you expect a text within an hour 62% of the time. How much did your distribution change?

The Fisher metric quantifies this. It measures how sensitive your predictions are to small changes in your model's parameters. High Fisher information means your predictions change a lot when you nudge the parameters—you're in a sensitive region of the manifold. Low Fisher information means your predictions are robust to small parameter changes—you're in a stable region.

Mathematically, the Fisher information is defined as the expected value of the squared rate of change of the log-probability. Don't worry about parsing that. The intuition matters more: Fisher information measures how much information your observations carry about the parameters of your model. It tells you how precisely you can estimate where you are on the manifold based on the data you receive.

And here's the key move: the Fisher information defines a metric on the manifold. It tells you how to measure distances. Two points are "close" if their Fisher-weighted difference is small—meaning their predictions are similar, they're hard to distinguish. Two points are "far" if their Fisher-weighted difference is large—meaning their predictions diverge, they're easy to tell apart.

This is why the Fisher metric is the natural ruler for statistical manifolds. It measures distance in terms of distinguishability. And distinguishability is what matters for minds, because minds are prediction machines. The relevant distance between two beliefs is how differently they predict the world.

What Distance Means

Once you have a metric, you have geometry. And the geometry of the Fisher metric reveals structure that flat numerical comparison misses.

Consider the space of all possible beliefs about a coin—what's the probability it lands heads? This is a one-dimensional manifold. Each point is a probability between 0 and 1. You might think this manifold would be a simple line segment, with uniform geometry from end to end.

It's not.

Near the edges—near 0 and near 1—the Fisher metric stretches. Distances become larger. A step from 99% to 99.5% is longer, in Fisher terms, than a step from 50% to 50.5%. The manifold is curved, compressed in the middle and stretched at the extremes.

Why? Because near certainty, small changes matter more. The difference between "definitely yes" and "almost definitely yes" is more consequential than the difference between "maybe yes" and "slightly more maybe yes." The metric captures this. It makes distances reflect informational significance, not numerical magnitude.

This is profound. It means the space of beliefs has intrinsic geometry—shape that isn't imposed from outside but emerges from the structure of information itself. The Fisher metric isn't a choice among many possible metrics. It's the metric that makes distance mean something. It's the unique ruler that measures distinguishability.

Curvature Emerges

From a metric, you can compute curvature. And the curvature of statistical manifolds is where things get interesting for understanding minds.

Curvature measures how much the manifold bends. In flat regions, parallel lines stay parallel. The geometry is Euclidean. You can move around without unexpected effects. In curved regions, parallel lines converge or diverge. The geometry distorts. Movement has consequences that wouldn't exist in flat space.

On statistical manifolds, curvature corresponds to sensitivity. High-curvature regions are where small changes in parameters produce large changes in predictions—where the model is touchy, reactive, easily perturbed. Low-curvature regions are where the model is robust—where you can nudge parameters without much happening.

Think about what this means for a nervous system.

A regulated nervous system has found a low-curvature region of its belief manifold. It has models of the world that are robust to small perturbations. When something unexpected happens, the prediction error is manageable. The system updates smoothly. It doesn't overreact because the geometry doesn't amplify small signals into large responses.

A dysregulated nervous system is stuck in a high-curvature region. The same small perturbation that a regulated system would absorb becomes, in the curved space, an enormous signal. The geometry amplifies. A creaking floorboard isn't just an unexpected sound—it's a trajectory through manifold regions where prediction error explodes and the whole system destabilizes.

The Fisher metric makes this precise. Curvature isn't a metaphor. It's a computable quantity derived from the metric. You can, in principle, measure it. You can locate high-curvature regions and understand why certain beliefs, certain configurations, certain states of mind are inherently more reactive than others.

Why Some Updates Are Harder

The metric also explains why some belief updates are easy and others are nearly impossible.

On a manifold with a metric, there's a natural notion of the shortest path between two points—the geodesic. This is the path of least resistance, the trajectory that minimizes total distance traveled. In flat space, geodesics are straight lines. On curved manifolds, they bend.

When you update your beliefs, you're moving across the manifold. In principle, you're trying to get from where you are (your current model) to where the evidence suggests you should be (a better model). The geodesic is the most efficient path.

But here's the thing: you don't always have access to the geodesic.

Some paths require crossing high-curvature regions. Every step through such a region is expensive—the metric is stretched, distances are long, the geometry penalizes you. What looks like a short journey on a naive map becomes an enormous trek when you account for curvature.

This is why some belief changes are hard. Not because people are stubborn. Not because they lack evidence. But because the path from their current belief to the target belief crosses geometric terrain that makes the journey costly.

Consider trying to convince someone of something that threatens their identity. The endpoint you're pointing to might be, in some objective sense, "not far" from where they are. But the path crosses regions where their self-model would have to deform, where prediction errors would spike, where the curvature of their manifold makes every step feel like a cliff. The resistance isn't psychological stubbornness—it's geometric cost.

Or consider therapeutic change. A client comes in with a belief—say, "I am fundamentally unlovable." The therapist can see that this belief is false, that evidence contradicts it, that a better model is available. But the client can't just "jump" to the better belief. They have to traverse the manifold. And the manifold between "unlovable" and "lovable" might be ferociously curved—full of regions where the very identity of the self becomes uncertain, where predictions about relationships collapse, where the cost of each step is enormous.

Therapy works, when it works, by finding paths. Not by pointing to the destination—the client often knows the destination. But by discovering routes through the geometry that don't require crossing the highest-curvature regions. By building capacity to tolerate curvature that once was intolerable. By slowly smoothing the manifold through repeated safe experiences until paths open up that were previously blocked.

The Shape of Learning

Learning, in this framework, is movement across the statistical manifold with the Fisher metric.

Good learning is efficient movement—following geodesics or near-geodesics, updating beliefs along paths of minimal cost, arriving at better models without unnecessary detours through high-curvature regions.

Bad learning is inefficient movement—getting stuck, taking long detours, crossing painful regions when smoother paths existed, or never moving at all because every direction seems too costly.

And some learning is impossible—not because of cognitive limitation but because the geometry doesn't permit it. There are configurations of the manifold where no path connects where you are to where you need to go. The topology is wrong (we'll get to topology). The space is disconnected. You literally cannot get there from here.

This reframes a lot of what we call learning difficulties. Some minds aren't bad at learning—they're starting from locations on the manifold that make certain destinations geometrically inaccessible. The issue isn't processing speed or memory capacity. It's manifold structure.

Conversely, some minds are exceptionally good at learning certain things because they start from locations that have geodesic access to the relevant regions. What looks like talent is sometimes just geometric advantage—being already close to where you need to go.

The Metric at Scale

Everything said so far applies to individual minds. But the Fisher metric doesn't care about scale. It applies wherever probability distributions exist—which is to say, everywhere that prediction exists.

A relationship is two probability distributions coupled together. Each person maintains a model of the other. The Fisher metric defines distances in each person's model-space. When we talk about "understanding" someone, we're talking about being close to them on the relevant manifold—having a model of them that makes similar predictions to their model of themselves.

Misunderstanding is distance. The farther apart our models, the more our predictions diverge, the less we can coordinate. Repair is distance reduction—finding paths that bring the models closer together.

An organization is a high-dimensional distribution over possible states—what the organization expects about its environment, its capabilities, its trajectory. The Fisher metric defines what it means for different parts of the organization to have "aligned" beliefs. When we say silos have formed, we're saying that different parts of the organization have drifted to distant regions of the manifold. The Fisher distance between them has grown so large that they can no longer predict each other.

A culture is a distribution so vast it encompasses millions of minds. The Fisher metric still applies. Cultural change is movement across this enormous manifold. Cultural coherence is geometric proximity—shared beliefs that cluster in the same region. Cultural polarization is distance—subpopulations drifting toward manifold regions so far apart that they can no longer recognize each other's predictions as reasonable.

The metric is the same at every scale. The geometry is the same. What changes is only the dimension of the manifold and the number of coupled points moving across it.

What This Gives Us

The Fisher information metric is technical. Its full mathematical treatment requires calculus, differential geometry, and statistical theory. This article has only gestured at the formalism.

But the intuitions matter independently of the formalism.

Distance between beliefs is about distinguishability, not numerical difference. Some belief changes are short journeys; others are treks across hostile terrain. The geometry of the manifold determines which is which. Curvature makes some regions reactive and others stable. The paths available to you depend on where you start.

These aren't philosophical claims. They're structural features of how probability distributions relate to each other—features that show up in minds, relationships, organizations, and cultures because all of these involve maintaining and updating probability distributions.

The Fisher metric is the ruler. Curvature—which we'll explore in depth next—is what the ruler reveals about shape. Together, they give us a mathematical vocabulary for talking about what has always been felt but rarely been formalized: the texture of belief, the difficulty of change, the geometry of minds moving through spaces of possibility.

The shape of surprise is the shape of your manifold. The distance to a new belief is measured in Fisher units. And the journey from where you are to where you're going crosses terrain that the metric makes precise.

Now we have a ruler. Next, we learn to read what it measures.

Comments ()