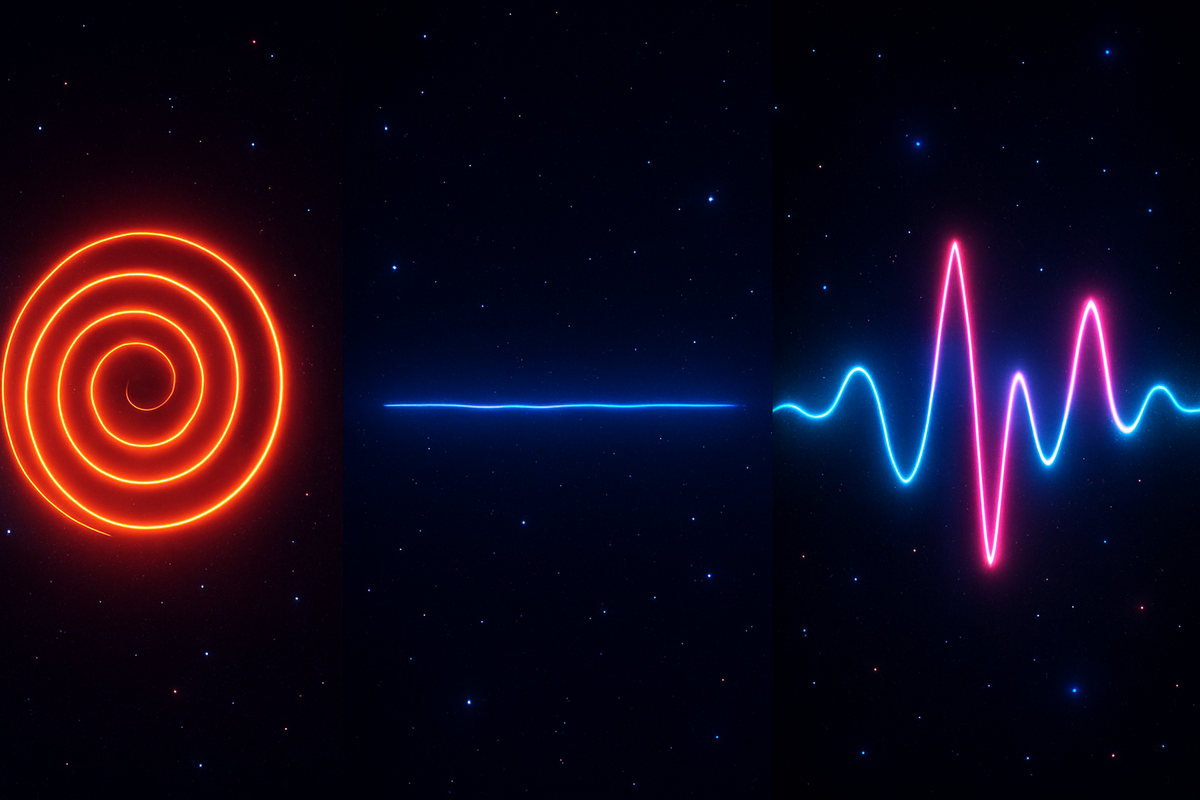

Three Failure Modes: Lock, Collapse, and Oscillation

Your nervous system fails in three distinct patterns: sympathetic lock (hyperactivation), dorsal collapse (shutdown), and chaotic oscillation. Each requires different therapeutic approaches to restore flexibility.

Three Failure Modes: Lock, Collapse, and Oscillation

Part 10 of Polyvagal Through the Coherence LensThe autonomic nervous system fails in distinct ways. Knowing which failure mode you're facing changes everything about intervention.Polyvagal theory describes three primary states: ventral vagal (social engagement), sympathetic (mobilization), and dorsal vagal (immobilization). Health involves flexible movement between states as circumstances require. Pathology involves getting stuck—locked into one state when the situation calls for another, or oscillating chaotically without settling.Each failure mode has its own signature, its own felt sense, its own coherence geometry. They require different responses.Failure Mode One: Sympathetic LockThe system is stuck in mobilization.The felt sense: Wired. Anxious. On edge. Can't settle. Racing thoughts, racing heart, racing through the day. Hypervigilant—scanning for threats, anticipating problems, preparing for impact. Sleep is difficult. Relaxation feels dangerous. Stillness is unbearable.The physiology: Elevated resting heart rate. Reduced HRV. Weak or absent RSA—heart and breath have decoupled. Chronically elevated cortisol. Muscle tension, especially in shoulders, jaw, and gut. Shallow, rapid breathing.The oscillatory signature: The sympathetic branch has captured the system's rhythm. Fast, tight oscillations dominate. The vagal brake can't engage—or engages briefly then releases. The system accelerates but can't decelerate.The coherence geometry: High curvature throughout the manifold. Everything is steep. Small perturbations produce large responses. The system is reactive, sensitive, ready to spike at any input. Dimensional collapse toward threat-relevant states—the full range of human experience has narrowed to variations on vigilance.What it looks like from outside: Restless, irritable, driven, controlling. May appear productive—sympathetic activation can fuel achievement—but the productivity is brittle. Relationships suffer because the system can't access the ventral vagal state required for genuine connection.Failure Mode Two: Dorsal CollapseThe system is stuck in immobilization.The felt sense: Flat. Numb. Disconnected. Everything takes enormous effort. The world feels distant, muted, unreal. Motivation is absent. Emotions are inaccessible or dampened. There's a heaviness that isn't quite sadness—more like absence.The physiology: Heart rate may be low but HRV is also low—the variability that indicates healthy vagal tone is missing. This is different from the low heart rate of a fit athlete; it's the low heart rate of shutdown. Digestion may be sluggish. Energy is depleted. The body feels heavy and slow.The oscillatory signature: The dorsal vagal branch has captured the system. Slow, low-amplitude oscillations dominate. The system has essentially powered down. Neither sympathetic activation nor ventral vagal engagement can break through.The coherence geometry: Amplitude collapse. The manifold has flattened—not smooth, but deflated. There's no energy for curvature spikes because there's no energy for anything. Dimensional collapse toward minimal states. The range of accessible experience has shrunk to a narrow band of muted functioning.What it looks like from outside: Withdrawn, passive, checked out. May appear lazy or unmotivated, but effort is genuinely unavailable—the system has insufficient resources to mobilize. Social engagement is minimal because the ventral vagal state can't be accessed.Failure Mode Three: Chaotic OscillationThe system swings between states unpredictably.The felt sense: Volatile. Unstable. One moment anxious and activated, the next flat and disconnected. The transitions happen fast and without apparent trigger. You don't know which version of yourself will show up. Exhausting—not just the states themselves but the constant shifting.The physiology: Heart rate is erratic. HRV may appear high but the variability is chaotic rather than coherent—lots of movement but no organized pattern. The system cycles through sympathetic and dorsal states without settling in either and without accessing ventral vagal stability.The oscillatory signature: No stable attractor. The system bounces between sympathetic acceleration and dorsal shutdown without finding the ventral vagal state that could regulate both. Phase relationships are unstable. Coupling is erratic. The stack of rhythms is desynchronized.The coherence geometry: Topological fragmentation. The manifold has separated into disconnected regions—sympathetic territory here, dorsal territory there, no smooth path between them. The system jumps across discontinuities rather than transitioning smoothly. Curvature is locally variable—steep in some regions, flat in others—but globally incoherent.What it looks like from outside: Unpredictable, confusing, "too much." Others don't know what to expect. The person may seem fine one moment and falling apart the next. Relationships are strained by the inconsistency. This pattern is particularly associated with disorganized attachment and complex trauma.Distinguishing the ModesThe three failure modes can be confused, especially from inside:Sympathetic lock can feel like energy: "I'm fine, I'm just busy." The constant activation feels normal after long enough. The inability to rest is reframed as drive.Dorsal collapse can look like depression: And it often co-occurs with depression. But the intervention frame matters—dorsal collapse is a nervous system state, not just a mood disorder.Chaotic oscillation can be misread as "emotional": The volatility is attributed to personality rather than nervous system dysregulation. "That's just how they are."The key diagnostic is the oscillatory signature:Lock: stuck in one pattern, can't transitionCollapse: minimal oscillation, flattened rangeOscillation: excessive transition, no stabilityAnd the key question: What happens when safety signals are present? In sympathetic lock, safety signals don't penetrate—the system keeps running. In dorsal collapse, safety signals can't activate—the system doesn't respond. In chaotic oscillation, safety signals produce temporary shifts but can't stabilize—the system recognizes them but can't hold them.Different Geometries, Different InterventionsEach failure mode requires a different approach:For sympathetic lock: The system needs help engaging the brake. Extended exhale breathing. Slow, rhythmic co-regulation. Grounding practices that bring attention into the body. The goal is to demonstrate that deceleration is safe, that stillness won't result in harm. The intervention adds drag to a system that's running too fast.For dorsal collapse: The system needs energy before it can regulate. Gentle activation—movement, cold exposure, engaging the environment. Not relaxation practices (the system is already too quiet) but gentle mobilization. The goal is to add enough signal that the system can start oscillating again. Then, once there's movement, help it organize.For chaotic oscillation: The system needs stabilization before it needs activation or calming. Predictable rhythms. Consistent external structure. Co-regulation with a steady, reliable other. The goal is to provide an attractor the system can settle into—not to calm it or activate it but to give it somewhere to land.Applying the wrong intervention to the wrong mode can backfire:Relaxation practices for dorsal collapse → more shutdownActivation practices for sympathetic lock → more accelerationEither extreme for chaotic oscillation → more destabilizationThe intervention must match the geometry.The Coherence PathAll three failure modes are departures from coherent function. The path back involves restoring the capacity for flexible state transition—the ability to move smoothly between ventral vagal, sympathetic, and dorsal states as circumstances require.From sympathetic lock: Learn that the brake can engage, that rest is possible, that deceleration doesn't mean death. The manifold needs smoothing—reducing the curvature that keeps the system hyper-reactive.From dorsal collapse: Learn that energy is available, that movement is possible, that the world can be engaged. The manifold needs reactivation—adding amplitude where collapse has flattened it.From chaotic oscillation: Learn that stability exists, that states can hold, that there is ground. The manifold needs integration—reconnecting fragmented regions so smooth transition becomes possible.In all cases, the goal is not a particular state but the capacity for state flexibility. Health is not perpetual calm. It's the ability to access calm, access activation, access rest—and to transition appropriately based on what the situation requires.Recognizing Your PatternMost people have a dominant failure mode—a direction the system tends toward under stress.Some run hot: stress pushes them toward sympathetic activation, and their challenge is learning to slow down.Some run cold: stress pushes them toward dorsal shutdown, and their challenge is learning to stay present.Some run erratic: stress pushes them toward instability, and their challenge is learning to find ground.Knowing your pattern is the first step. Not because it defines you—patterns can change—but because it tells you what kind of support your system needs.The nervous system is not infinitely flexible. It has its tendencies, its grooves, its preferred failure modes. Working with those tendencies, rather than against them, is more efficient than pretending they don't exist.Next: Hysteresis—why the system can't simply return to where it was, and what that means for recovery.Series: Polyvagal Through the Coherence LensArticle: 10 of 15Tags: polyvagal, sympathetic nervous system, dorsal vagal, autonomic states, trauma

Comments ()