Trust Is Expensive to Build and Cheap to Destroy

In 1993, a hedge fund called Long-Term Capital Management attracted the most prestigious team ever assembled in finance. Two Nobel Prize-winning economists. A former vice chairman of the Federal Reserve. The intellectual elite of quantitative trading.

Their models were brilliant. Their returns were spectacular—40% annually in the first years. They were so confident in their strategies that they leveraged $5 billion in capital into $125 billion in positions.

Then Russia defaulted on its debt, and the models stopped working.

In six weeks, LTCM lost $4.6 billion. The Federal Reserve organized an emergency bailout—not because LTCM was important, but because its collapse threatened to cascade through the entire financial system. Trust between counterparties was evaporating. If LTCM's positions unwound chaotically, the contagion might be unstoppable.

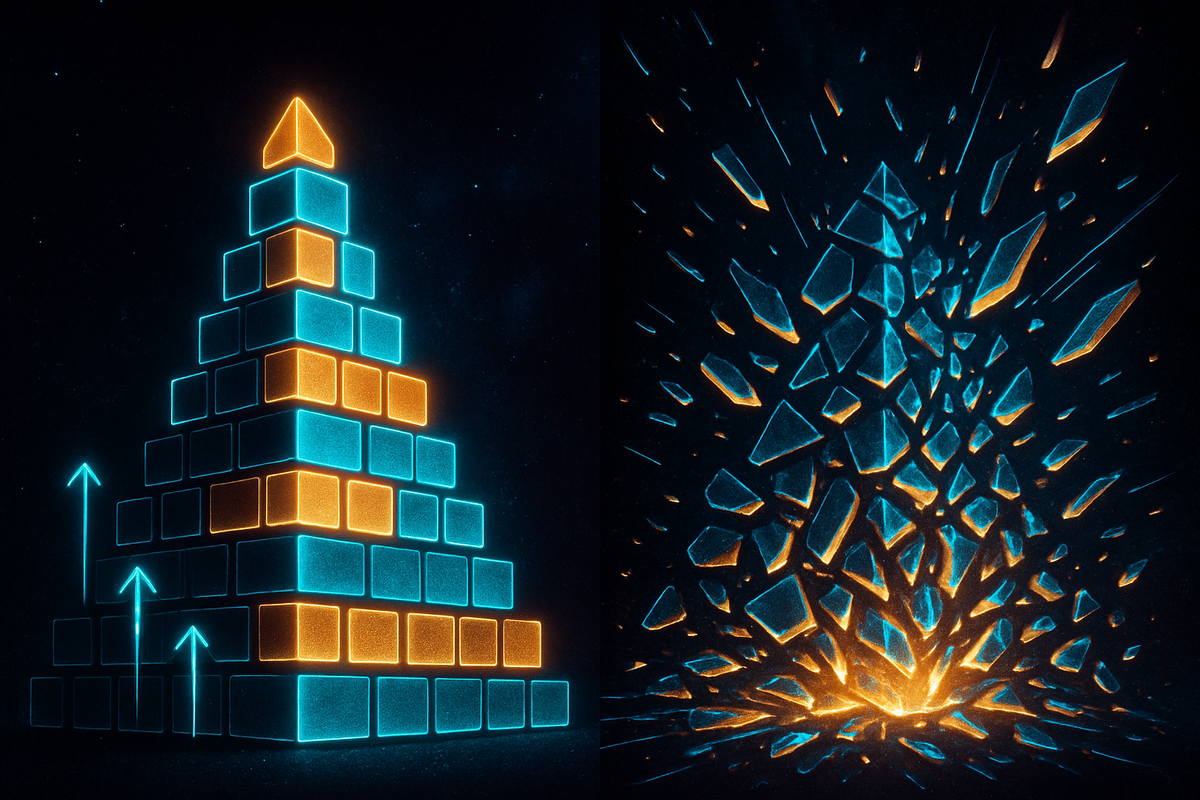

It took years to build the trust that enabled LTCM's trading. It took weeks to destroy it. This asymmetry—trust is expensive to build and cheap to destroy—is one of the most important facts about how societies work.

The Trust Asymmetry

Why is trust so much easier to destroy than to create?

Building trust requires repeated positive interactions. Each successful transaction, each promise kept, each expectation met—these accumulate into a reputation for reliability. The process is slow because trust requires evidence, and evidence takes time to generate.

Destroying trust requires one betrayal. A single defection, a single promise broken, a single expectation violated—these can erase years of accumulated goodwill. The process is fast because trust is a prediction about future behavior, and new evidence about defection updates that prediction dramatically.

This asymmetry is rational. If someone has betrayed you once, the base rate for future betrayal has changed. It's appropriate to weight recent evidence heavily. The person who burned you last week is a better predictor of future burning than the person who was reliable for ten years before that.

But the asymmetry creates problems. It means that trust equilibria are fragile. It means that a single bad actor can damage trust for an entire category—one Enron poisons the well for all companies, one corrupt cop damages trust in all police. It means that building trust is a slow investment that can be wiped out in a moment.

Trust is a commons. Everyone who maintains trust contributes to the pool. Everyone who betrays trust drains it. And the tragedy of the commons applies: individual incentives to defect can destroy the collective good.

The Math of Trust

Game theorists have quantified these dynamics.

In a one-shot prisoner's dilemma, defection is the rational strategy. If you'll never interact again, why cooperate? But most real interactions are repeated—you'll see these people again, do business again, need their cooperation again.

In repeated games, cooperation becomes possible. If you defect today, others can punish you tomorrow. The threat of future punishment makes cooperation incentive-compatible. Trust emerges as a rational strategy when the shadow of the future is long enough.

But the math reveals the fragility. Cooperation in repeated games depends on:

Probability of future interaction. If you're unlikely to see someone again, defection becomes more attractive. This is why anonymous online interactions breed more toxicity than face-to-face—the shadow of the future is shorter.

Discount rate. If you value future payoffs less than present payoffs, defection looks better. Desperate people, dying institutions, those with short time horizons—they're more likely to betray trust.

Detection probability. If you can defect without being caught, the punishment mechanism breaks down. Trust requires transparency—mechanisms that reveal defection—or it unravels.

Coordination on punishment. Punishing defectors is costly. If others won't join the punishment, it's not worth doing. Trust requires coordinated enforcement.

Group size. In small groups, everyone knows everyone's reputation. Defection is visible and punishable. In large groups, anonymity protects defectors. Scaling trust requires formal institutions that substitute for personal knowledge.

When any of these parameters degrade, trust becomes harder to maintain. The repeated game equilibrium unravels. Cooperation collapses into defection.

This framework reveals something important: trust isn't a feeling. It's a rational response to institutional structure. In a well-designed game, trusting is smart because cooperation pays. In a poorly-designed game, distrusting is smart because defection pays. The failure of trust is usually an institutional failure, not a moral one.

Trust as Infrastructure

Economists call this the problem of "transaction costs." Every transaction involves costs beyond the price paid: searching for a trading partner, verifying their reliability, negotiating terms, enforcing agreements.

In low-trust environments, transaction costs are enormous. You have to verify everything. Contracts are thick with clauses anticipating betrayal. Every interaction requires extensive safeguards.

In high-trust environments, transaction costs are low. A handshake is enough. Contracts are thin because most terms are implicit and understood. You can focus on creating value instead of protecting yourself from predation.

Trust is economic infrastructure, like roads or electricity. When trust infrastructure works well, it's invisible—you don't notice the transaction costs you're not paying. When trust infrastructure fails, everything becomes harder and more expensive.

Consider what's required to buy groceries in a high-trust society:

You walk into a store assuming the food isn't poisoned (regulatory trust), the prices are fair enough (market trust), your credit card won't be stolen (security trust), and the transaction will be honored (legal trust). You don't verify any of this. You just buy milk and leave.

Now consider buying food in a low-trust environment:

You might need to know the vendor personally. You might inspect every item for tampering. You might only deal in cash because electronic payments are unreliable. You might need a relationship with someone who knows the vendor's reputation. Every transaction requires verification that high-trust environments take for granted.

The difference is transaction costs. And those costs compound across millions of transactions into the difference between prosperous societies and struggling ones.

Why Trust Collapses

If trust is so valuable, why does it ever collapse?

Individual incentives vs. collective outcomes. Building trust benefits everyone, but betraying trust can benefit the betrayer. The individual who defects captures gains while imposing costs on the collective. Classic tragedy of the commons.

Asymmetric information. Trust works when trustworthiness is visible. But people can hide their true type. The person who seems trustworthy might be running a long con. Adverse selection means the trustworthy can be driven out by the untrustworthy.

Shock propagation. When one betrayal occurs, it updates beliefs about everyone. If you discover one institution was lying, you update your probability that others are lying. Trust collapses cascade—once distrust starts spreading, it becomes self-reinforcing.

Institutional decay. The machinery that produces trust—regulatory oversight, legal enforcement, reputational systems—requires maintenance. When institutions degrade, trust production degrades with them. The degradation is often invisible until the system fails.

Generational discontinuity. Trust takes a generation to build. But knowledge of why trust exists can be lost in a generation. People who grow up in high-trust environments may not understand what maintains trust—and may make changes that destroy it.

Short-term optimization. Every system that builds trust can be exploited in the short term by someone willing to spend down the accumulated trust. The MBA who cuts quality to boost quarterly earnings. The politician who lies for immediate advantage. The institution that trades reputation for expedience. The trust was built by predecessors; the destroyer captures the gains and moves on.

The Cost of Low Trust

Low-trust societies pay enormous costs:

Economic costs. Without trust, complex economic coordination becomes difficult. Firms stay small because extending trust to strangers is risky. Investment is lower because property rights seem uncertain. Growth is slower because every transaction is friction-heavy.

Political costs. Low-trust environments breed authoritarian leaders who promise to cut through corruption and dysfunction. But authoritarians tend to destroy institutions further, creating a spiral of declining trust.

Social costs. When you can't trust strangers, you retreat to family and clan. The radius of cooperation shrinks. The scale of what's possible shrinks with it.

Psychological costs. Living in a low-trust environment is exhausting. You're constantly vigilant, constantly verifying, constantly expecting betrayal. The cognitive load of distrust is a tax on every interaction.

Consider the contrast between Denmark and Sudan. In Denmark, you can leave your baby's stroller outside a café. In Sudan, you can't trust that state employees will do their jobs without bribes. The GDP difference is vast—but the difference in transaction costs is vaster.

Studies have attempted to quantify this. One famous estimate suggested that if you could raise trust levels in Nigeria to those of Sweden, Nigeria's economy would more than double. Not from new resources or better technology—purely from the reduction in transaction costs. Trust is that valuable.

Or consider the simpler example of contract enforcement. In high-trust societies, most contracts are never litigated because both parties assume they'll be honored. In low-trust societies, contract enforcement is both more common and less reliable—you need the legal system more, but the legal system works worse. The result is that people avoid complex contracts entirely, which limits the complexity of what can be organized.

Trust in Modernity

Modernity solved a profound trust problem: how to cooperate with strangers.

In traditional societies, trust extended only to those you knew personally—family, clan, village. Interacting with strangers required elaborate rituals of hospitality, or was simply avoided.

Modern institutions—legal systems, markets, professional standards, credentials, regulatory agencies—created trust with strangers at scale. You don't need to know your doctor personally; the credential guarantees a floor of competence. You don't need to know the company you're buying from; contract law guarantees recourse.

This trust infrastructure enabled everything distinctive about modernity: large-scale economic coordination, specialized expertise, anonymous exchange, complex supply chains.

But the infrastructure is not self-maintaining. It requires ongoing investment. It requires people who believe in it. It requires enforcement mechanisms that work. When any of these falter, the trust machinery starts to break.

The Fragility We Face

The current moment is concerning.

Trust in institutions—government, media, science, corporations—has declined across most developed democracies over the past several decades. The decline is well-documented in surveys and visible in behavior.

Some of this is appropriate. Some institutions weren't trustworthy, and increased scrutiny has revealed failures that warrant distrust.

But some of the decline seems pathological. Trust can collapse past the point justified by institutional quality. Once distrust becomes the default, even trustworthy actors face suspicion. The cooperative equilibrium can break even when cooperation remains optimal.

This series explores the economics of that machinery—what produces trust, what destroys it, and whether it can be rebuilt.

What makes this difficult is that trust and trustworthiness are intertwined but distinct. Trust is the belief that others will cooperate. Trustworthiness is the reality of whether they will. In healthy equilibria, the two align. In pathological situations, they decouple.

You can have high trust without trustworthiness—the con man's ideal, where suckers believe despite evidence. This is unstable; eventually the betrayals surface.

You can have trustworthiness without trust—the reformer's problem, where institutions have improved but the public hasn't updated. This is also unstable; the distrust creates its own dynamics.

The economics of trust is about the mechanisms that produce both—and what happens when those mechanisms fail.

The Takeaway

Trust is economic infrastructure. It's expensive to build, cheap to destroy, and essential for complex coordination.

The asymmetry is fundamental: building trust requires repeated positive interactions; destroying it requires one betrayal. This makes trust equilibria fragile—always susceptible to unraveling.

Understanding the economics of trust is necessary for understanding why some societies flourish while others struggle, why institutions matter so much, and what happens when the trust machinery fails.

You're living inside trust infrastructure you can't see. The question is whether that infrastructure is being maintained—or whether it's quietly decaying beneath you.

Further Reading

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge University Press. - Williamson, O. E. (1985). The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. Free Press. - Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. Free Press.

This is Part 1 of the Economics of Trust series. Next: "Douglass North: Institutions Matter"

Comments ()