Vector Fields: Arrows at Every Point

A vector field assigns a vector to every point in space. That's it. But that simple definition is the foundation for describing almost every continuous physical phenomenon that involves direction.

Think about wind. At every point in the atmosphere, the air has a velocity—both speed and direction. That's a vector field. Think about gravity. At every point in space, there's a force pulling toward massive objects. That's a vector field. Think about the flow of water in a river, the electric field around a charged particle, the magnetic field around a wire, the temperature gradient in a metal bar. All vector fields.

Regular functions map numbers to numbers: f(x) = x². Vector fields map positions to vectors: F(x, y, z) = (something, something, something). The input is a location. The output is a vector at that location. The field exists everywhere continuously.

This shift from discrete functions to continuous fields is fundamental. You're no longer asking "what's the value at this point?" You're asking "what's happening everywhere?" The mathematics changes to match.

Notation and Components

In two dimensions, a vector field typically looks like:

F(x, y) = (P(x, y), Q(x, y))

or equivalently:

F(x, y) = P(x, y)i + Q(x, y)j

The components P and Q are scalar functions that give the x and y components of the vector at each point. The unit vectors i and j point in the x and y directions.

In three dimensions:

F(x, y, z) = (P(x, y, z), Q(x, y, z), R(x, y, z))

or:

F(x, y, z) = P(x, y, z)i + Q(x, y, z)j + R(x, y, z)k

The component functions P, Q, and R can be anything—polynomials, trig functions, exponentials, whatever. The field is just the package that bundles them together and assigns a vector to each point.

Example: F(x, y) = (-y, x)

At the point (1, 0), the vector is (0, 1)—pointing up. At the point (0, 1), the vector is (-1, 0)—pointing left. At the point (-1, 0), the vector is (0, -1)—pointing down. At the point (0, -1), the vector is (1, 0)—pointing right.

This field rotates counterclockwise around the origin. It represents circular flow.

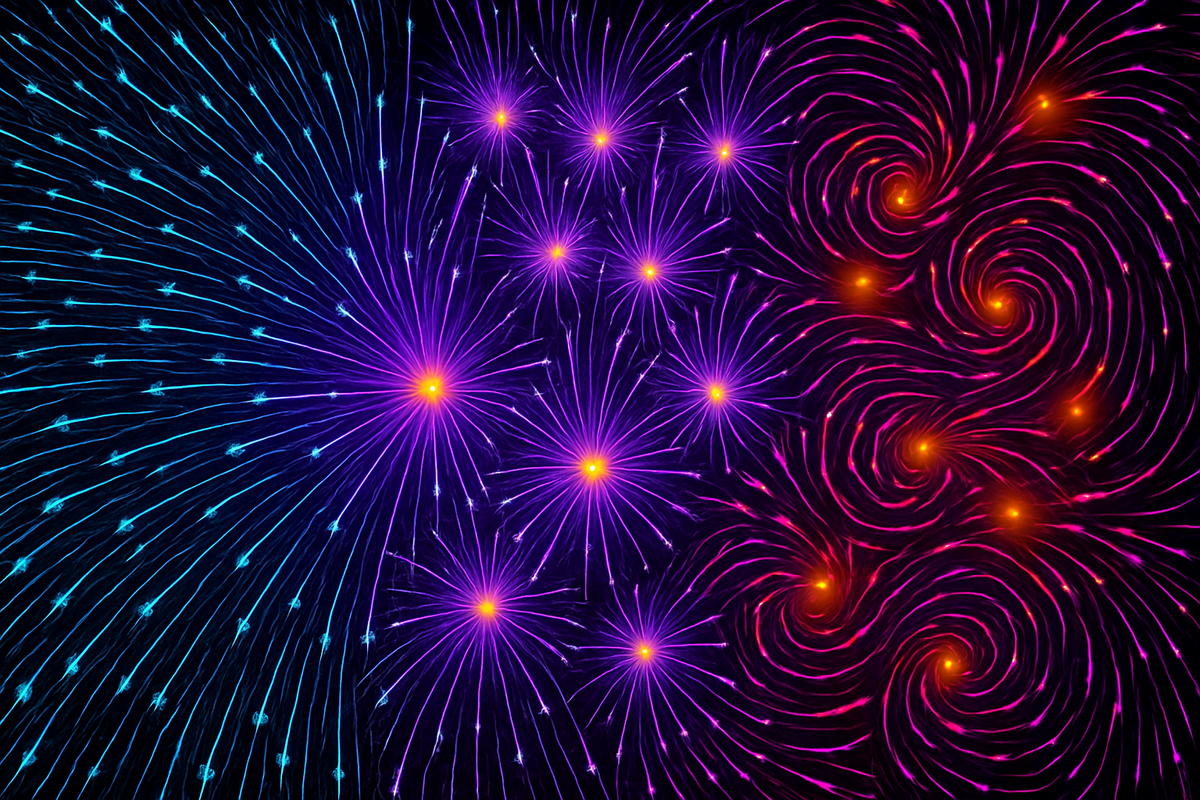

Visualization Methods

Vector fields in 2D are usually drawn as arrow plots. You sample the field at a grid of points, draw an arrow at each point showing the vector's direction, and scale the arrow length to show magnitude. Dense arrows mean strong field; sparse arrows mean weak field.

This works beautifully for 2D fields on paper. For 3D fields, it gets messier. You can draw arrows in a 3D space, but visual clutter becomes a problem fast. Alternative visualizations include:

Field lines (or streamlines): curves that are everywhere tangent to the field. If you drop a particle into the field, it would follow a field line. These show flow structure without overwhelming you with arrows.

Color mapping: use color to represent magnitude, contour lines to show field direction. Works better for some fields than others.

Cross-sections: slice the 3D field along planes and visualize the 2D restriction. You lose global structure but gain clarity about local behavior.

The choice of visualization depends on what you're trying to understand about the field. Are you tracking flow? Use field lines. Are you finding maxima? Use color maps. Are you studying local structure? Use arrow plots at high resolution in a small region.

Conservative vs Non-Conservative Fields

A vector field is conservative if it's the gradient of some scalar function. That is, there exists a function φ (called the potential) such that F = ∇φ.

Conservative fields have special properties:

- Line integrals are path-independent. The work done moving from point A to point B depends only on the endpoints, not the route taken.

- The curl is zero everywhere.

- Line integrals around closed loops are always zero.

Gravitational fields are conservative. The work done lifting an object depends only on height change, not on the path. Electrostatic fields are conservative. The voltage difference between two points is path-independent.

Non-conservative fields don't have these properties. Magnetic fields are generally non-conservative. Friction forces are non-conservative—the work done depends on path length. Rotating flows are non-conservative.

The distinction matters enormously in physics. Conservative forces have potential energies. Non-conservative forces don't. Conservation of energy works differently depending on whether the forces are conservative.

Examples of Physical Vector Fields

Gravitational field: Points toward masses, falls off as 1/r². Conservative. The potential function is gravitational potential energy.

Electric field: Points away from positive charges, toward negative charges. For static charges, it's conservative. For time-varying charges, it's not.

Magnetic field: Circles around currents. Never conservative. Has no scalar potential in the usual sense.

Velocity field of fluid flow: At each point in the fluid, there's a velocity. Might be conservative (irrotational flow) or not (vortices).

Heat flux: Points from hot to cold, proportional to temperature gradient. This is F = -k∇T, where k is thermal conductivity. The field is conservative if temperature is in steady state.

Force fields in general: Any force that varies with position defines a vector field. Spring forces, air resistance, pressure gradients—all vector fields.

The mathematics of vector fields is abstract, but the physical interpretations are everywhere. Once you see the pattern, you start noticing vector fields in every domain of physics.

The Geometric Picture

Here's the key geometric intuition: a vector field partitions space into arrows. Each arrow says "if you're here, this is the direction and magnitude of [whatever the field represents]."

For velocity fields, the arrows show flow direction. For force fields, they show the force direction. For gradient fields, they show the direction of steepest increase.

You can think of the field as a "texture" on space. Space isn't empty—it's filled with directional structure. Every point has a vector attached to it. The field is the totality of all those attachments.

This is why the notation F(x, y, z) is slightly misleading. It suggests you're "evaluating a function" at a point. But really, the field exists everywhere simultaneously. You're sampling it at a point, not creating it.

The geometric picture makes certain properties intuitive:

- Divergence measures how much the field spreads out from a point. If arrows are radiating outward, divergence is positive. If they're converging, divergence is negative.

- Curl measures how much the field rotates around a point. If arrows circulate, curl is nonzero.

- Field lines are integral curves—they follow the flow. Starting at any point and stepping in the direction of the field traces out a field line.

These operators (divergence, curl) will be defined precisely later. For now, the geometric picture is enough: fields have local structure, and that structure has measurable properties.

Scalar Fields vs Vector Fields

Scalar fields assign a number to each point. Temperature, pressure, density, electric potential—these are scalar fields.

Vector fields assign a vector to each point. Velocity, force, electric field, magnetic field—these are vector fields.

The two are related through differential operators:

- Gradient turns scalar fields into vector fields. ∇φ takes a scalar function φ and produces a vector field pointing in the direction of steepest increase.

- Divergence and dot product integration turn vector fields into scalar fields. Divergence measures spreading. Flux integrals sum up how much field crosses a surface.

- Curl takes vector fields to vector fields. It measures rotation and produces a new vector field describing the axis and magnitude of swirl.

The interplay between scalar and vector fields is central to vector calculus. Many physical laws relate the two: electric field is the gradient of electric potential. Temperature gradient drives heat flux. Pressure gradient drives fluid flow.

Understanding when something is naturally a scalar field vs a vector field is part of learning to think physically. Temperature is a scalar—it has no direction. Heat flux is a vector—it flows in a direction. Confusing them leads to nonsense.

Field Strength and Density

Vector magnitude tells you field strength. In a velocity field, magnitude is speed. In an electric field, magnitude is force per unit charge.

Field line density visually represents field strength. Where lines are close together, the field is strong. Where they spread out, the field is weak. This isn't just a visualization trick—it's a mathematical fact related to flux and the divergence theorem.

For a field satisfying ∇ · F = 0 (divergence-free, or "solenoidal"), field line density is proportional to magnitude. This is why magnetic field lines work the way they do: magnetism has no sources (∇ · B = 0), so field line density directly represents field strength.

For fields with divergence, field lines begin at sources and end at sinks. Positive divergence means lines are radiating out. Negative divergence means lines are converging. The density still represents magnitude, but now the lines aren't closed loops—they have endpoints.

Coordinate Systems and Vector Fields

Vector fields can be expressed in different coordinate systems: Cartesian (x, y, z), cylindrical (r, θ, z), spherical (r, θ, φ), or others.

The same physical field looks different in different coordinates. In Cartesian coordinates, a radial field might be:

F(x, y, z) = (x, y, z) / √(x² + y² + z²)

In spherical coordinates, the same field is just:

F(r, θ, φ) = (1, 0, 0)

One component. Much simpler. This is why choosing the right coordinate system matters—it can make calculations trivial or nightmarish.

The transformation rules between coordinate systems are nontrivial. Vector components transform covariantly (they're contravariant vectors, technically), which means you can't just plug in the coordinate transformation. You also need to rotate the basis vectors.

For most practical work, you pick the coordinate system that matches the symmetry of the problem. Spherical for central forces. Cylindrical for anything with axial symmetry. Cartesian when there's no obvious symmetry.

Operations on Vector Fields

You can add vector fields: (F + G)(p) = F(p) + G(p). Vector addition at each point.

You can scale vector fields: (cF)(p) = cF(p). Scalar multiplication at each point.

You can take the dot product of two vector fields: (F · G)(p) = F(p) · G(p). This produces a scalar field.

You can take the cross product of two vector fields: (F × G)(p) = F(p) × G(p). This produces another vector field.

These operations are pointwise—they happen at each point independently. The field structure allows you to do algebra on infinite-dimensional objects (functions) as if they were finite-dimensional vectors. This is the power of the function space perspective.

The Function Space View

Mathematically, vector fields are elements of a function space. The set of all smooth vector fields on R³ forms a vector space itself. You can add them, scale them, and take linear combinations.

This abstract perspective becomes useful when you start doing calculus on vector fields. The derivative of a vector field (in various senses: divergence, curl, gradient if you start from a scalar) is another field. Integration of a vector field over a path or surface produces a number.

The operators ∇, ∇·, and ∇× are linear operators on function spaces. They map vector fields (or scalar fields) to other vector fields (or scalar fields). The fundamental theorems of vector calculus—Green's, Stokes', Divergence—are statements about these operators.

This is a higher level of abstraction than just "fields assign vectors to points," but it's where the real mathematical power lives. Once you see fields as elements of a vector space, the calculus machinery becomes operator theory, and lots of tools from linear algebra become available.

Singularities and Domain Restrictions

Not all fields are defined everywhere. The gravitational field of a point mass blows up at the mass location. The electric field of a point charge diverges at the charge. These are singularities—points where the field is undefined or infinite.

Similarly, some fields are only defined on restricted domains. The velocity field of fluid inside a pipe exists only inside the pipe. The electric field inside a conductor is zero (in electrostatics), but it exists outside.

When working with vector fields, always ask: what's the domain? Where is this field defined? Are there singularities? The fundamental theorems all require certain regularity conditions—smoothness, bounded domain, no singularities in the region of integration. Violating those conditions can make the theorems fail.

Field Dynamics vs Field Statics

So far, we've been treating vector fields as static—they exist in space and don't change in time. But many physical fields are dynamic. The velocity field of a turbulent fluid changes every instant. Electromagnetic fields propagate as waves.

Dynamic fields are time-dependent: F(x, y, z, t). At each instant, you have a spatial field. Over time, the field evolves.

The equations governing field dynamics are usually partial differential equations (PDEs). The Navier-Stokes equations govern fluid flow. Maxwell's equations govern electromagnetic fields. The wave equation governs vibration and propagation.

Vector calculus provides the spatial operators (gradient, divergence, curl) that appear in these PDEs. Time derivatives handle the dynamics. Combining spatial and temporal derivatives gives you the full field equations.

Most of this series focuses on static fields or instantaneous snapshots of dynamic fields. But understanding the spatial structure is the first step toward understanding dynamics.

Why Vector Fields Matter

Vector fields aren't just a mathematical abstraction. They're the natural language for describing continuous phenomena in space.

Discrete models (particles, graphs, networks) work for some problems. But for fields—wind, waves, electricity, magnetism, heat, stress—you need continuous mathematics. And for anything directional, you need vectors.

The alternative to vector fields is describing everything in components. "The x-component of velocity is vx, the y-component is vy, the z-component is vz." That works, but it's clunky and obscures the geometric structure. Treating the field as a unified object—a function from space to vectors—makes the structure visible.

Once you adopt the field perspective, lots of physical laws simplify. Maxwell's equations are four vector equations. In component form, they'd be a mess of 12 scalar equations. Fluid dynamics is three coupled PDEs for the velocity vector field. In components, it's harder to see the structure.

The field concept scales. Tensor fields (generalizations of vector fields) describe stress, strain, curvature. Spinor fields describe quantum particles. Gauge fields describe fundamental forces. The idea of "assign an object to each point in space" is the foundation of modern physics.

The Path Forward

Vector fields are the objects. Now we need operations on them.

Integration: Line integrals sum the field along curves. Surface integrals sum the field over surfaces. These extend the basic integral to structured paths through space.

Differentiation: Gradient, divergence, and curl are the differential operators on fields. They measure local properties—steepness, spreading, rotation.

Theorems: Green's, Stokes', and Divergence Theorems connect integration and differentiation. They're the fundamental theorems of vector calculus, generalizing the basic ∫f' = f(b) - f(a) to higher dimensions.

Understanding vector fields is the prerequisite for all of this. They're the stage on which vector calculus is performed. Every operation, every theorem, every application starts with a field.

Now that we have the fields defined, we can start calculating with them.

Part 2 of the Vector Calculus series.

Previous: What Is Vector Calculus? The Mathematics of Fields Next: Line Integrals: Integrating Along Curves

Comments ()