The Virome: The Viruses Living Inside You (And Why That's Mostly Fine)

Series: Microbiome Revolution | Part: 6 of 8 Primary Tag: FRONTIER SCIENCE Keywords: virome, bacteriophage, phage, gut viruses, viral diversity, phage therapy

After COVID-19, most people hear "virus" and think "threat." Fair enough. Viruses can kill you. They've shaped human history through plagues and pandemics. We spend billions developing vaccines and antivirals to fight them.

But here's something that might take a minute to absorb: you contain roughly 380 trillion viruses right now. That's ten times more viruses than human cells. Every day, trillions of these viruses are replicating inside you, infecting cells, completing their life cycles.

And you're fine.

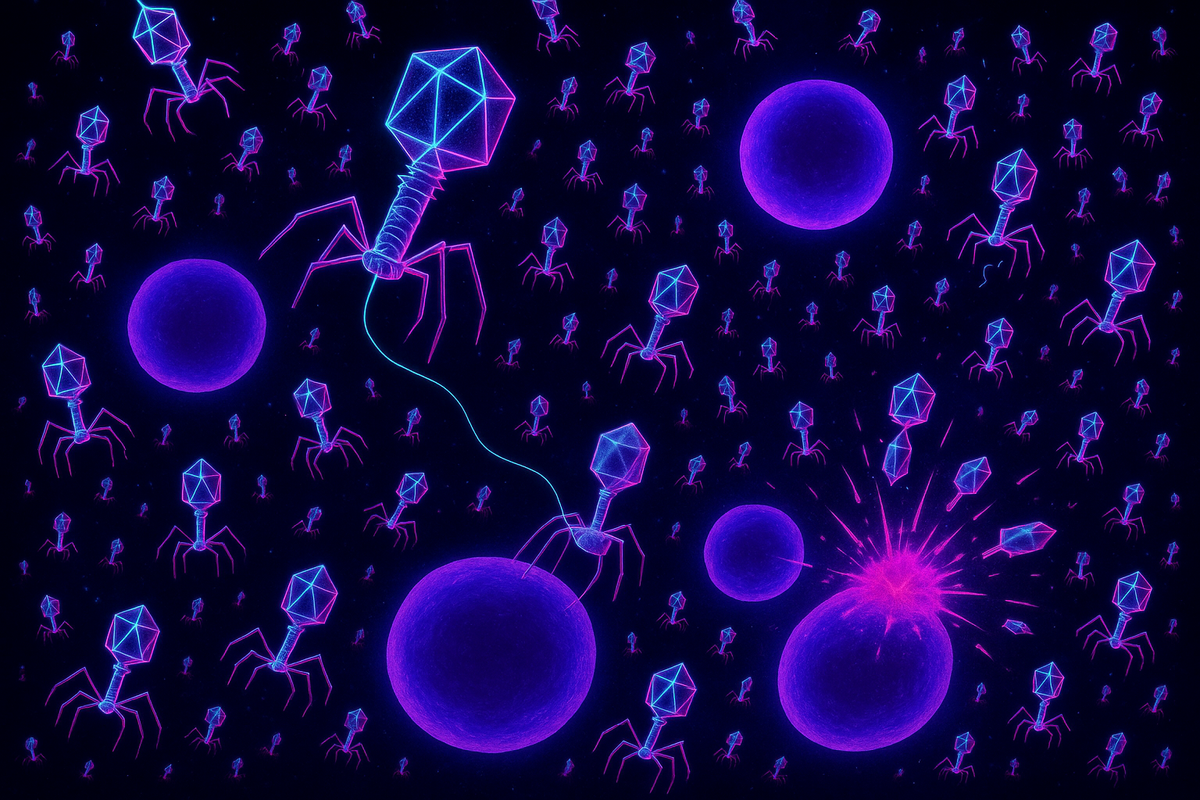

Most viruses in your body aren't infecting you. They're infecting your bacteria. These are bacteriophages—phages for short—viruses that exclusively target bacteria. They're the most abundant biological entities on Earth, and they've been running a parallel infection ecosystem inside your gut that microbiome science mostly ignored until the last decade.

The virome is the viral component of your microbiome, and it's not just a weird footnote. It might be one of the key regulators of bacterial community dynamics, immune function, and disease. We just didn't have the tools to see it until recently.

The Most Abundant Life Form You've Never Heard Of

Bacteriophages were discovered in 1915, just two years after bacteria were accepted as the cause of disease. Frederick Twort in England and Félix d'Hérelle in France independently observed something that could kill bacteria—something invisible, something that passed through filters that trapped bacteria, something that multiplied in the presence of its bacterial hosts.

D'Hérelle named them bacteriophages: "bacteria eaters." He immediately recognized their therapeutic potential. If viruses could kill bacteria, maybe they could treat bacterial infections. Before antibiotics existed, phage therapy was a real option. D'Hérelle treated dysentery, cholera, and plague with phage preparations. The results were inconsistent—sometimes dramatic cures, sometimes nothing—but promising enough to launch a phage industry.

Then Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin. Antibiotics were reliable, standardized, and manufacturable. Phages were finicky, specific, and poorly understood. The West abandoned phage therapy and went all-in on antibiotics. The Soviet Union kept developing phages—they had limited antibiotic access—but their research was published in Russian and largely ignored by Western science.

For nearly a century, bacteriophages became a curiosity. Molecular biologists used them as tools for genetic research (restriction enzymes, CRISPR, and many other discoveries came from studying phages), but the ecological role of phages in human health was almost completely overlooked.

This began changing around 2010, when DNA sequencing became cheap enough to survey what viruses were actually present in human samples. The answer was: an astonishing abundance of phages, plus some other viruses, forming a community we barely understood.

What's Actually In There

The human virome has three main components:

Bacteriophages: By far the most numerous. Your gut contains an estimated 10^12 to 10^15 phage particles, mostly belonging to a few major families. The Caudovirales order (tailed phages) dominates, including Siphoviridae, Myoviridae, and Podoviridae families. But there's also a mysterious group called crAss-like phages (yes, really—named after the Cross-Assembly software used to discover them) that were only identified in 2014 and appear to be among the most common phages in human guts worldwide.

Eukaryotic viruses: These are viruses that infect human cells or could potentially infect them. Most people carry low levels of viruses like torque teno virus (TTV), GB virus C, and others that seem to establish chronic, asymptomatic infections. Whether these are truly commensal (neutral or beneficial) or just low-grade pathogens that our immune systems keep in check is debated.

Plant and food viruses: When you eat plants, you eat plant viruses. These show up in gut virome surveys but can't replicate in animal cells. They're passengers, not residents.

The bacteriophage community is the most important for understanding gut ecology. These phages are in a constant evolutionary arms race with their bacterial hosts. They kill bacteria, bacteria evolve resistance, phages evolve to overcome resistance. This dynamic has been running for billions of years, and it's happening inside you right now.

How Phages Shape the Microbiome

Here's where it gets interesting. Bacteriophages don't just passively exist alongside bacteria. They actively shape which bacteria thrive and which decline.

Predation dynamics: Phages hunt specific bacterial hosts. Most phages are specialists—they infect only one species, sometimes only specific strains of one species. When a bacterial population grows large, it becomes a bigger target. More bacteria = more successful phage infections = more bacterial death. This creates kill-the-winner dynamics: whichever bacteria are thriving get disproportionately attacked, preventing any single species from completely dominating.

This matters for microbiome stability. Kill-the-winner dynamics promote diversity. They prevent competitive exclusion, where one bacterium outcompetes all others. Phages act like a distributed regulatory system, trimming back whoever's getting too successful.

Lysogeny: Not all phages immediately kill their hosts. Some integrate into bacterial DNA and become prophages—viral genomes riding along in bacteria, replicated every time the bacterium divides. Under certain conditions (stress, damage, etc.), prophages activate, replicate, and burst out of the cell.

While integrated, prophages can change their hosts. They carry genes that modify bacterial behavior—sometimes virulence factors, sometimes metabolic functions, sometimes immunity to other phages. A bacterium carrying a prophage is subtly different from one without. Prophages are horizontal gene transfer vectors, moving genetic information between bacteria.

An estimated 40-50% of gut bacteria carry prophages. The virome isn't separate from the microbiome—it's interleaved, with viral genomes woven into bacterial chromosomes.

Bacterial gene transfer: Phages can pick up bacterial genes during replication and transfer them to new hosts (transduction). This is another horizontal gene transfer mechanism. Antibiotic resistance genes, metabolic capabilities, and other traits can spread through bacterial populations via phage-mediated transfer.

The CrAssphage Mystery

In 2014, researchers analyzing human gut virome data discovered something unprecedented: a completely new virus, present in roughly 50% of people tested, and abundant—one of the most common components of the human gut virome.

They called it crAssphage (for cross-assembly phage, the computational method used to find it). It's a large bacteriophage, about 97,000 base pairs of DNA. Despite being incredibly common, it had never been observed because standard laboratory techniques couldn't culture it or its bacterial host.

CrAssphage infects Bacteroides species, among the dominant bacteria in the human gut. It's found in human populations worldwide. It appears in ancient fecal samples. It's been called "the most abundant and prevalent human-associated virus known."

And we discovered it in 2014. We missed the most common human-associated virus until genomic methods revealed it.

This gives you a sense of how much we don't know about the virome. CrAssphage wasn't the only surprise—dozens of previously unknown phage families have been identified in the past decade. The virome was hiding in plain sight because we didn't have eyes to see it.

Viromes and Disease

If phages shape bacterial communities, and bacterial communities shape health, then phage composition might influence disease. The research is still early, but patterns are emerging.

Inflammatory bowel disease: IBD patients consistently show altered virome composition compared to healthy controls. There's typically reduced phage diversity and shifts in the types of phages present. Whether this is cause or effect is unclear—inflammation might change conditions in ways that select for different phages, or phage changes might contribute to bacterial shifts that drive inflammation.

C. difficile infection: Remember fecal transplants? Some researchers think phages are a key part of why FMT works. Healthy donor material contains phages that might target C. diff or the bacteria that support it. Phage communities transfer along with bacteria, and they might be doing some of the ecological work.

Obesity and metabolic disease: Altered virome composition has been observed in obesity, with some phages associated with bacteria that promote metabolic dysfunction. The causal relationships are murky, but the correlations exist.

Type 1 diabetes: The virome of children who develop type 1 diabetes differs from those who don't, even before diagnosis. This suggests viral changes might precede—and potentially contribute to—autoimmune disease development.

Neurological conditions: Remember the gut-brain axis? Phages that alter bacterial communities that produce neurotransmitters might indirectly affect brain function. This is speculative but biologically plausible.

The recurring finding: disease states associate with reduced virome diversity, similar to reduced bacterial diversity. A healthy ecosystem is a diverse ecosystem, in viruses as in bacteria.

Phage Therapy: The Comeback

Remember that pre-antibiotic phage therapy that the West abandoned? It's coming back.

The driver is antibiotic resistance. We're running out of antibiotics. Bacteria evolve resistance faster than we develop new drugs. The WHO calls antimicrobial resistance "one of the greatest threats to global health." We need alternatives.

Phages offer something antibiotics can't: specificity and co-evolution.

Antibiotics are broad-spectrum. They kill the target pathogen but also devastate the commensal microbiome. Phages are narrow—often targeting a single species or even strain. You could kill a pathogen while leaving the rest of the microbiome intact.

And when bacteria evolve phage resistance, you can evolve phages to overcome it. The phage-bacteria arms race has been running for billions of years. Phages have been evolving to kill bacteria the whole time. You can exploit this evolutionary library.

The modern phage therapy approach combines traditional insights with modern technology:

Phage cocktails: Use multiple phages targeting the same bacterium. The bacterium might evolve resistance to one phage, but probably not all of them simultaneously.

Personalized phage medicine: Sequence the patient's pathogen, identify phages in libraries that target it, test efficacy, then treat. This requires diagnostic infrastructure but delivers precision.

Engineered phages: Modify phages to be more effective, to carry payloads like CRISPR systems that cut bacterial genomes, or to evade bacterial defense mechanisms.

The FDA approved the first phage therapy under compassionate use in 2016 for a man with a multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infection who was dying. The phage treatment cleared the infection. He survived. Other compassionate-use cases have followed.

Clinical trials are underway for various conditions. The Eliava Institute in Georgia (the country, not the state) has been doing phage therapy continuously since the Soviet era and has decades of clinical experience. Western medicine is slowly catching up.

The Phage-Immune Connection

Phages don't just interact with bacteria. They interact with your immune system too.

Most phages can't infect human cells—they don't have the machinery. But they're recognized by the immune system as foreign particles. The immune response to phages is generally muted compared to pathogenic viruses, but it's not zero.

Some research suggests phages might have immunomodulatory effects. Phages in the gut mucus layer might influence inflammatory signaling. Phages that lyse bacteria release bacterial components, which can stimulate or dampen immune responses depending on context.

There's even evidence that phages can cross the gut barrier and enter circulation in small numbers—a process called phage translocation. What systemic effects this might have is unknown. The immune system probably clears most circulating phages quickly, but the implications of regular low-level phage translocation haven't been studied carefully.

The phage-immune interface is understudied. We're only beginning to understand how viral passengers interact with their human host's defenses.

Beyond the Gut: Body-Wide Virome

The gut virome is the most studied because stool is easy to collect. But viruses aren't confined to the gut.

Oral virome: Your mouth has its own distinct viral community. Phages targeting oral bacteria, plus some human-infecting viruses. Oral virome composition associates with periodontal disease.

Respiratory virome: Phages targeting respiratory bacteria plus chronic viral residents like torque teno virus.

Skin virome: Yes, your skin has viruses too. Phages and eukaryotic viruses residing in skin's microbial ecosystem.

Blood virome: Even blood, traditionally thought of as sterile, contains viral particles. Mostly TTV and other apparently commensal viruses, plus phage DNA likely translocated from gut.

Each body site has its own viral ecology, shaped by the bacteria present, the immune environment, and the physical conditions. The virome is as site-specific as the microbiome.

The Ecological View

The virome forces an ecological perspective on human biology. You're not an organism with some bacterial passengers. You're a multi-kingdom ecosystem. Bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses all coexist, interact, and shape each other's populations.

Phages and bacteria have been co-evolving for billions of years. Their relationships predate multicellular life. When those relationships moved into animal guts, they brought that ancient dynamic with them. Your gut is a battleground and a partnership simultaneously, with viral predators keeping bacterial prey populations in check, and bacteria evolving defenses, and phages evolving counters, generation after generation, faster than anything else in biology.

The stability of your microbiome—its ability to resist pathogen invasion, to recover from antibiotic disruption, to maintain diversity—probably depends partly on virome dynamics we're only beginning to understand.

The Coherence Perspective

From a coherence frame, the virome is the regulatory layer above the bacterial layer. Phages don't just exist in the microbiome; they govern it. They impose constraints on bacterial population dynamics. They transfer information between bacteria. They respond to density signals, targeting overgrowth, promoting diversity.

If the microbiome is an ecosystem, phages are the predators, the population control mechanisms, the information transfer network. They're what keeps the system from collapsing into monoculture or spiraling into chaos.

The stability of complex systems often depends on feedback loops. In the gut, phages provide negative feedback on bacterial growth—more bacteria means more infection means more bacterial death. This kind of regulation promotes the oscillating equilibrium that characterizes healthy ecosystems.

When we disrupt the microbiome—with antibiotics, with diet, with stress—we're also disrupting the virome. And when the virome changes, it may change how the bacterial community responds to perturbation. The viral layer might be why some people bounce back from antibiotic treatment quickly and others don't.

We can't understand the microbiome in isolation from the virome. The two are coupled. And both are coupled to the immune system, which is coupled to diet and stress and behavior. It's systems all the way down.

What We Still Don't Know

The virome is one of the most understudied aspects of human biology. Basic questions remain open:

- What determines individual virome composition? (Genetics? Diet? Early exposure? Random chance?) - How stable is the virome over time? - Can we deliberately manipulate the virome for therapeutic benefit? - What eukaryotic viruses are truly commensal versus low-grade pathogens? - How do prophages affect bacterial behavior at the community level? - What are the long-term consequences of virome disruption?

The tools to answer these questions—deep sequencing, computational methods, phage cultivation techniques—have only existed for a decade or so. The field is young. We're in the era of discovery, not yet the era of application.

But the shape of the answers is becoming visible. The virome matters. It's not noise; it's signal. And understanding it will be necessary for understanding the microbiome, the immune system, and the integrated ecology of human health.

Further Reading

- Shkoporov, A.N. & Hill, C. (2019). "Bacteriophages of the Human Gut: The 'Known Unknown' of the Microbiome." Cell Host & Microbe. - Dutilh, B.E. et al. (2014). "A highly abundant bacteriophage discovered in the unknown sequences of human faecal metagenomes." Nature Communications. (The crAssphage paper) - Górski, A. et al. (2017). "Phages targeting infected tissues: novel approach to phage therapy." Future Microbiology. - Norman, J.M. et al. (2015). "Disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome in inflammatory bowel disease." Cell. - Schooley, R.T. et al. (2017). "Development and Use of Personalized Bacteriophage-Based Therapeutic Cocktails to Treat a Patient with a Disseminated Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection." Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

This is Part 6 of the Microbiome Revolution series, exploring how trillions of bacteria shape your body and mind. Next: "Skin, Mouth, and Beyond: The Other Microbiomes."

Comments ()